Curating Comics Canons Daniel Clowes and Art Spiegelman’S Private Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Les Reprints Made in U.S

Pas d'équivoques pour BD/VF chez Glénat qui s'intitule elle-même la BD de papa. La série les reprints des Rip Kirby d'Alex Raymond constitue une excellente initiation au bon vieux roman poli- made in U.S. cier de derrière les fagots pour adolescents en quête de suspense. Malheureusement le format des vignettes la rend difficile à lire alors que la par Claude-Anne Parmegiani, parution en album broché permet un prix de la Joie par les livres vente abordable pour un public jeune. Chez Futuropolis, la présentation soignée de la col- Ils s'appellent Pim, Pam, Poum, Terry, Po- lection « Copyright » la destine aux pères et aux peye, Illico, Blondie ou bien Flash Gordon, Rip grands frères. Dommage que le format en lon- Kirby, Mandrake, Superman, Prince Valiant... gueur et l'épais cartonnage ne facilitent pas la Ils sont tantôt petits, moches, rigolos et dé- manipulation des trois volumes de Popeye (Se- brouillards, tantôt grands, beaux, forts et invin- gar) ou de Superman (Siegel et Shuster), qui cibles. Ils sont tous supers ! mais ce sont quand plairaient dès douze ans sous une forme plus même les copains d'enfance de nos parents. populaire et à un prix plus abordable. Car à cet Alors pourquoi cette brusque nostalgie de l'âge âge-là, on lit et on relit « ses » BD jusqu'à les d'or de la BD américaine chez les éditeurs ? savoir par cœur, et pour ça pas d'autre moyen Pierre Horay avait déjà ouvert la voie en réé- que les acheter ; on peut pas compter sur les ditant depuis une dizaine d'années les classi- parents pour vous les offrir ! Quand ils les ques de la BD dont le chef-d'œuvre de Windsor aiment, ils les gardent pour eux, sinon ils trou- Me Cay : Little Nemo. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

United Media Licensing Newsletter 24

Plug-in content June, 2009 The 2009 Licensing International Expo kicks off on June 2 in its new location in the west at the Mandalay Bay Convention Center in Las Vegas. Be sure to stop by United Media's booth (#917) to check out what's happening with our entire portfolio of brands. Each property has a great story to tell and opportunities for growth. DOMESTIC NEWS: HALLMARK TAPPED AS EXCLUSIVE RETAIL HOME FOR THE 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF PEANUTS IN 2010 As United Media gears up for the launch of the 60th anniversary program for PEANUTS, long term partner Hallmark has signed on as Peanuts the exclusive domestic retail partner for the brand in 2010. Beginning in January, merchandise, including seasonal and everyday plush, Hallmark Keepsake Ornaments and greetings cards will be featured front of store in all Hallmark Gold Crown doors. For almost 50 years, PEANUTS has enjoyed great success at Hallmark, so kicking off this iconic celebration with such a strong and dedicated partner, who also happens to be celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2010, is sure to set the tone for this momentous anniversary. FANCY NANCY IS TRES MANIFIQUE! Fancy Nancy continues to garner recognition, extend retail partnerships and sign new deals. This month, Fancy Nancy received two nominations for the 2009 LIMA Fancy Nancy International Licensing Excellence Awards for Best Character Brand License – Hard Goods and Best Character Brand Program of the Year. Target and Jakks Pacific extended their exclusive partnership for Fancy Nancy dolls and role-play through April 2010! Look out for the following products at retail soon: shoes from ACI International, HBA from SJ Creations, t-shirts from Junk Food, fabric from Springs Creative Product Group and backpacks from Accessory Innovations. -

AL PLASTINOPLASTINO His Era, Plastino Was the Last Surviving Penciler/Inker of Superman Comic Books

LAST SUPERMAN STANDING: THE STANDING: SUPERMAN LAST LAST SUPERMAN STANDING Alfred John Plastino might not be as famous as the creators of Nancy, Joe Palooka, Batman, and other classic daily and THE STORY Sunday newspaper strips, but he worked on many of them. And of ALAL PLASTINOPLASTINO his era, Plastino was the last surviving penciler/inker of Superman comic books. In these pages, the artist remembers both his struggles and triumphs in the world of cartooning and beyond. A near-century of history and insights shared by Al, his family, and contemporaries Allen Bellman, Nick Cardy, Joe Giella, and Carmine Infantino— along with successors Jon Bogdanove, Jerry Ordway, and Mark Waid —paint a layered portrait of Plastino’s life and career. From the author and designer team of Curt Swan: A Life In Comics. PLASTINO AL Foreword by Paul Levitz. STORY EDDY ZENO EDDY An illustrated biography EDDY ZENO Plastino cover.indd 1 8/19/14 2:26 PM LAST SUPERMAN STANDING THE STORY AL PLASTINO EDDY ZENO Plastino.indd 1 9/3/14 1:52 PM Contents Foreword By Paul Levitz .................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 6 Globs Of Clay, Flecks Of Paint ...................................................................................... 8 Harry “A” ............................................................................................................................ 16 The War -

September 2007 Caa News

NEWSLETTER OF THE COLLEGE ART ASSOCIATION VOLUME 32 NUMBER 5 SEPTEMBER 2007 CAA NEWS Cultural Heritage in Iraq SEPTEMBER 2007 CAA NEWS 2 CONTENTS FEATURES 3 Donny George Is Dallas–Fort Worth Convocation Speaker FEATURES 4 Cultural Heritage in Iraq: A Conversation with Donny George 7 Exhibitions in Dallas and Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum 8 Assessment in Art History 13 Art-History Survey and Art- Appreciation Courses 13 Lucy Oakley Appointed caa.reviews Editor-in-Chief 17 The Bookshelf NEW IN THE NEWS 18 Closing of CAA Department Christopher Howard 19 National Career-Development Workshops for Artists FROM THE CAA NEWS EDITOR 19 MFA and PhD Fellowships Christopher Howard is editor of CAA News. 21 Mentors Needed for Career Fair 22 Participating in Mentoring Sessions With this issue, CAA begins the not-so-long road to the next 22 Projectionists and Room Monitors Needed Annual Conference, held February 20–23, 2008, in Dallas and 24 Exhibit Your Work at the Dallas–Fort Fort Worth, Texas. The annual Conference Registration and Worth Conference Information booklet, to be mailed to you later this month, 24 Annual Conference Update contains full registration details, information on special tours, workshops, and events at area museums, Career Fair instruc- CURRENTS tions, and much more. This publication, as well as additional 26 Publications updates, will be posted to http://conference.collegeart.org/ 27 Advocacy Update 2008 in early October. Be sure to bookmark that webpage! 27 Capwiz E-Advocacy This and forthcoming issues of CAA News will also con- tain crucial conference information. On the next page, we 28 CAA News announce Donny George as our Convocation speaker. -

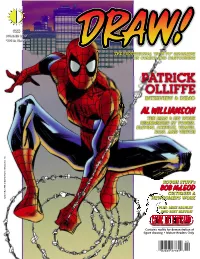

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade. -

I Peanuts Get Fuzzy Dilbert Robotman

24 domenica 10 novembre 2002 71 Sono formate da 60 minuti - 72 Va all'altare col velo e lo strascico - 73 Si oppone al toro in borsa - 74 Lunga fila di dimostranti. VERTICALI 1 Secondo in breve - 2 Stracci - 3 Campicello in cui si coltivano zucchi- ne e pomodori - 4 Socialisti Italiani - 5 Attivo (abbr.) - 6 Una bottiglia di forma cilindrica - 7 Iniziali di Pacinot- ti - 8 Verso del corvo - 9 Corridori motociclisti - 10 Un difetto visivo - 11 Il partito di Bettino Craxi (sigla) - 12 Il fiume di Cremona - 13 La pro- Uno, due o tre? vincia pugliese di Martina Franca (si- gla) - 14 Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità - 15 L'alta pressione san- guigna - 17 Saccoccia - 18 Il suo ini- zio si festeggia il primo di gennaio - Tra le varie attività che non esistono più c'è quella del postie- 20 Un nome composto di uomo - 22 re. Sapete dire cosa faceva? Vi proponiamo tre risposte, una La casa degli eschimesi - 26 Scrisse La condizione umana - 29 Merenda sui sola delle quali è esatta. Quale? prati - 31 Marco della tv - 33 Grosso sgabello cilindrico imbottito - 34 Idee, opinioni - 36 Il... sostegno del pappagallo - 38 Con tap nel nome del 1 - Era l'addetto a collocare gli spettatori a teatro, condu- ballo di Fred Astaire - 39 Teatro Ama- toriale Italiano - 40 Circa sessanta mi- cendoli al posto prenotato. ORIZZONTALI zioni - 21 Vasti - 23 Centro della buito al pontefice - 49 Qui non inizia nuti - 41 Funesto, luttuoso - 42 Tribu- 2 Sigla di Como - 4 Marca automobili- Brianza - 24 Scherzi anche mancini - - 50 Iniziali della Dandini - 52 Siste- nale -

Alternate PDF Version

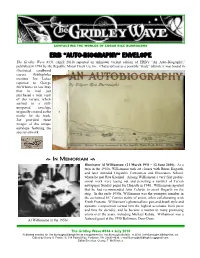

CONTACTING THE WORLDS OF EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS ERB “AUTO-BIOGRAPHY” ENVELOPE The Gridley Wave #331 (April 2010) reported an unknown variant edition of ERB’s “An Auto-Biography,” published in 1916 by the Republic Motor Truck Co, Inc. Characterized as a possible “trade” edition, it was bound in illustrated card board covers. Bibliophiles member Joe Lukes reported to George McWhorter in late May that he had just purchased a mint copy of this variant, which arrived in a still- unopened envelope originally created as the mailer for the book. Joe provided these imag es of this unique envelope featuring the special artwork. In Memoriam Illustrator Al Williamson (21 March 1931 – 12 June 2010). As a teen in the 1940s, Williamson took art classes with Burne Hogarth, and later attended Hogarth's Cartoonists and Illustrators School, where he met Roy Krenkel. Among Williamson’s very first profes- sional work were laying out and penciling a number of Tarzan newspaper Sunday pages for Hogarth in 1948. Williamson reported that he had recommended John Celardo to assist Hogarth on the strip. In the early 1950s, Williamson was the youngest member in the acclaimed EC Comics stable of artists, often collaborating with Frank Frazetta. Williamson’s photorealistic pen-and-brush style and dynamic composition earned him the highest accolades from peers and fans for decades, and he became a mentor to many promising artists over the years, including Michael Kaluta. Williamson was a Al Williamson in the 1950s. featured guest at the 1998 Baltimore Dum-Dum. The Gridley Wave #334 ♦ July 2010 Published monthly for The Burroughs Bibliophiles as a supplement to The Burroughs Bulletin. -

Peanuts and Politics New Exhibition at the Charles M

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – April 6, 2016 Gina Huntsinger, Marketing Director Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center (707) 579-4452 #268 [email protected] “Whether through newspapers, television, books or movies, Peanuts has made us laugh, challenged us to think, and encouraged us to dream.” – President Bill Clinton “Through the years you have brought joy and laughter into millions of homes worldwide with your comic strips, television specials, and books. Characters like Charlie Brown, Snoopy, and Lucy have a warm place in our national heart.” – President Ronald Reagan Sometimes history repeats itself. Snoopy weighed in during the tumultuous election of 1968. ©1968 Peanuts Worldwide LLC Peanuts and Politics New Exhibition at the Charles M. Schulz Museum Mr. Schulz Goes to Washington April 30 through December 4, 2016 (Santa Rosa, CA) In this election year a little laughter from the Peanuts Gang is in order. The lighter- side of politics and its intersection with the life of Charles Schulz is the focus of the newest exhibition, Mr. Schulz Goes to Washington, running April 30 through December 4, 2016 at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California. This exhibition features original presidential- themed Peanuts comic strips, correspondence with several American presidents, and Peanuts memorabilia, including campaign bumper stickers, buttons, and banners. Visitors of all ages can cast a ballot for their favorite Peanuts character, or write a postcard to the future president. 2301 Hardies Lane ● Santa Rosa, CA 95403 U.S.A. ● 707.579.4452 ● Fax 707.579.4436 www.SchulzMuseum.org © 2016 Charles M. Schulz Museum | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED | A non-profit 501(c)(3) organization PEANUTS © 2016 Peanuts Worldwide, LLC Charles Schulz learned the value of service from his father, who was deeply connected in his community of St.