City of Cincinnati Independent Monitor's Final Report December

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2010 Nana News

Published by :The North Avondale Neighborhood Association 617 Clinton Springs Ave. (29) Voice mail: (513) 221.6166 Email: [email protected] Website : Northavondalecincinnati.com Volume XXXXIX, No.10 SUMMER 2010 President: Bill Stevens Administrator/Editor: Charlene Morse PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE In the past month I have made an effort to try and genuinely colleges nationwide, including Princeton and Harvard, want as a identify the things about North Avondale that make it the kind member of the student body because of superior intellect? Yes, of place that entices me and Rita to live here. I am amazed by he plays sports too, but his real forte is academic achievement. the endless reasons why North Avondale is North Avondale. I am proud Brandon is part of the NA community. The community is alive with various cultural backgrounds and Cynthia Payne and Virginia Thomas make me want to search all are proud of their heritage. North Avondale has an inherent for ways to enhance the appearance of my lawn which I already attitude of wanting best quality of life for families. NA citizens feel looks fairly appealing. Drive by these ladies’ homes on stand up for their beliefs, even if not popular with all. NA is North Fred Shuttlesworth and view pride and effort only a few minutes from downtown and close to shopping, personified. I love neighbors that make our community look sporting events, good food, music and about anything else you nice. think you want. NA’s architectural design is marvelous and Linda Mathews who lives on Eaton Lane is a dynamite unique. -

DON't SHOOT: a Radical Approach to the Problem

aNNals Of cRimE dON’T shoot A radical approach to the problem of gang violence. BY JOHN sEaBROOK n April, 2006, two brutal street killings hot spots almost as fearful of the police as in the Over-the-Rhine section of Cin- they are of the criminals. As Whalen, a cinnatiI spread fear through the city. A big, bearlike man with a friendly Irish white suburban mother of three, who was face, put it to me recently, “You say, ‘O.K., trying to buy drugs at the corner of Four- we’re going to arrest everyone who jay- teenth and Race, got into an argument walks.’ So who do you arrest? Someone’s with the dealer, and was shot and killed. grandmother, or the milkman, or some A few days later, on the same block, four guy who has just worked a sixteen-hour white kids, also from the suburbs—a boy day and is trying to get home as fast as he at the wheel, three girls in the back—were can. It’s bullshit. Even in high-crime buying drugs when a black man walked neighborhoods, there are a lot of honest up to the car and shot the boy in the head. people living there. Meanwhile, the real These incidents, coming within days bad guys—they know a sweep is on, so of each other, contributed to the public’s they just stay inside until things cool off.” impression that violent crime in the streets The Cincinnati Police Department’s was out of control. In fact, much of the vi- relationship with the black community olence was occurring between people who had been a poisonous issue for years. -

Report 6-Public Safety.Qxd

PUBLIC SAFETY 6 ptown must be a safe, attractive and walkable place for its residents, employees, students and visitors. While overall crime in Cincinnati is down, Uptown U continues to suffer from a poor public safety image. The April 2001 civil disturbances in nearby Over the Rhine and longstanding perceptions about the entire Center City area have branded Uptown in the public imagination as a place "you don't go" or as a place you do not linger. While there are actual crime problems in isolated areas that contribute to the poor image, including areas of entrenched drug dealing and youth robberies, the transformation of the public perception will require a concentrated effort through every facet of the Consortium's business. Current Public Safety According to Cincinnati 2002-2003 police department issued data, overall citywide crime is The neighborhoods of Uptown are divided into down by 2%. The Uptown figures paint a picture two districts by the Cincinnati Police Department of even greater improvement: (CPD): districts four and five that cover approximately four square miles and serve • Violent crime in Uptown has decreased at a 50,000 residents. In addition, each of the higher rate than the rest of the City. Consortium's Members operates a private • District 4 crime was down 4.5% from 2002 security force; although their size and capacity to 2003. greatly vary amongst the institutions. • While District 5 has relative low levels of violent crime, it has high incidences burglary The University of Cincinnati's police force is andlarceny which attribute to a net increase armed and has arrest powers. -

The Importance of Small Units of Aggregation: Trajectories of Crime at Addresses in Cincinnati, Ohio, 1998–2012

VOLUME17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 20–36 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ The Importance of Small Units of Aggregation: Trajectories of crime at addresses in Cincinnati, Ohio, 1998–2012 Troy C. Paynea and Kathleen Gallagherb a University of Alaska at Anchorage b The Analysis Group A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N We describe the temporal and spatial patterns of crime at unique addresses over a 15-year period, 1998-2012, in a medium-sized Midwestern city. Group-based trajectory analysis of police incidents recorded by the Cincinnati Police Department are combined with geographic analysis for the entire city, while also highlighting individual address points in one high-crime neighborhood. We find that six trajectories adequately describe the city-wide data, with the low-stable crime trajectory comprising the majority of the places, while the high-stable crime trajectory is just 2.5% of addresses yet consistently has one-third of crime, which accounts for a disproportionate amount of crime. Similar to previous research at the street-block level, small differences in city-wide trends from 1998-2012 obscure large differences within trajectories. Places with very different trajectories of crime are very often located on the same street segment. Nearly all high-crime addresses exist among a cloud of low-crime places. This suggests that characteristics of individual addresses are of importance both to crime theory and crime prevention practice. -

1973 Annual Report of 'The

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. =0=.·.=::;=::;::::::;;:====::::::·::::::~;;:;;:r::::· =.·;:;;;t __ tit::m;;;J;;'Q''''';'- ~d!i.. ~::--_---~.lH~~'P~~7~ Iii :-~. .'J ;: ".,,~c.~,~ :(i .) I} o " ********************************** :J 0 \~ o , .... :._'". I' I, -~ , . POLlCE STATISTICS OF CINCINNATI, \) l, 1973 ANNUAL REPORT OF 'THE DIVISION OF POLICE , 1---~ '. ~ -; t'":--:' ;\ CINCINNAT'l POLICE 17lst" YEAR o .-'j. ~·I··I CITY OF CINCINNATI DEPARTMENT OF SAFETY DIVISION OF POLICE 171st YEAR ! POLICE STATISTICS OF CINCINNATI Ij 1 1973 ANNUAL REPORT 1 OF THE DIVISION OF POLICE I CARL V. GOODIN POLlCE CHIEF , Compiled and Published by the Records Section or the Cineinn"li Police Division JUNE,1974 CINCINNATI. OHIO ·.~ 1973 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIVISION OF POLICE CONTENTS Foreword Report to the Safety Director 1973 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIVISION OF POLICE Organization Chart FOREWORD I Personnel Data [ i~, C~""""I" Table 1 Since 1929 the Cincinnati Police Division has compiled Offenses and Clearances data and statistics in the present format via the Annual Report for research and analysis. We attempt to pI'~sent Tables 7 and 11 annually without interpretation the IImost asked for Arrests, Criminal data in such manner that similar information can be com p'ared from year to year. Permission will be given to '!abIes 24, 25,}5 and 41 reproduce any part of this report upon request. Arrests, Adult Traffic Table 46 Arrests, Juvenil~ Statistics-Criminal and Traffic Carl V. Goodin Police Chief Police District and Reporting Area Analyses '~ , Tables 75, 76, 76A, ,76B, 760, 76D, 85, 66, 871', 878, 8781 and '5 r Stolen and Recovered Property Table ,6 and '7 Traffic Accidents Tables 104, 106, Ill, 112 and 115 f!,- Miscellaneous Services and Incidents by Reporting Area Tab18. -

Police-Community Relations in Cincinnati Year Three Evaluation Report

Police-Community Relations in Cincinnati Year Three Evaluation Report Terry Schell, Greg Ridgeway, Travis L. Dixon, Susan Turner, K. Jack Riley Sponsored by the City of Cincinnati Safety and Justice A RAND INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, AND ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM The research described in this report was sponsored by the City of Cincinnati and was conducted under the auspices of the Safety and Justice Program within RAND Infrastructure, Safety, and Environment (ISE). The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research organization providing objective analysis and effective solutions that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors around the world. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. R® is a registered trademark. © Copyright 2007 RAND Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from RAND. Published 2007 by the RAND Corporation 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 4570 Fifth Avenue, Suite 600, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-2665 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] Preface This is the third annual report that the RAND Corporation has produced on police-com- munity relations in Cincinnati. The reports are required under RAND’s contract to evaluate whether an agreement on police-community relations in Cincinnati is achieving its goals. -

Police-Community Relations in Cincinnati Year Two Evaluation Report

INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, AND ENVIRONMENT THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Infrastructure, Safety, and Environment View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Police-Community Relations in Cincinnati Year Two Evaluation Report Greg Ridgeway, Terry Schell, K. -

Situational Crime Prevention at Specific Locations in Community Context: Place and Neighborhood Effects

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Situational Crime Prevention at Specific Locations in Community Context: Place and Neighborhood Effects Author: John E. Eck, Tamara Madensen, Troy Payne, Pamela Wilcox, Bonnie S. Fisher, Heidi Scherer Document No.: 229364 Date Received: January 2010 Award Number: 2005-IJ-CX-0030 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Situational Crime Prevention at Specific Locations in Community Context: Place and Neighborhood Effects John E. Eck, Tamara Madensen, Troy Payne, Pamela Wilcox, Bonnie S. Fisher, Heidi Scherer University of Cincinnati November, 2009 This project was supported by Grant No. 2005-IJ-CX-0030 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication/program/exhibition are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Justice. -

Existing Condition Report

BACKGROUND The lack of convenient and healthy food options in urban centers is an issue that academics, politicians and regular citizens have sought to address. The debate about these ‘food deserts’ has been present in Cincinnati for a number of years as the Kroger Company, headquartered in Cincinnati, has closed older stores within the city. Many fear that the Kroger location in Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills neighborhood will meet the same fate as some of Kroger’s other closed Cincinnati urban locations in Roselawn and Westwood. Kroger is currently renovating and expanding their Corryville store, a store in close proximity to the store in Walnut Hills. The neighbors and neighborhood activists in Walnut Hills fear that their neighborhood grocery will be shut down once the renovation to the Corryville location is finished. The Kroger store in Walnut Hills has been open since 1983 and has operated at a loss every year except for 1984. There was concern in 2008 that the store would be shut down however Kroger decided to extend its lease on the land. Kroger also spent approximately $250,000 making improvements to the interior of the store and changing the management with a goal of making the store profitable. The Walnut Hills Redevelopment Corporation has also taken up the challenge of making the store profitable. Their ‘Buy 25’ initiative asks that area shoppers come to the Walnut Hills Kroger twice a month and spend at least twenty five dollars during each of those visits. This report has been prepared by a group of students in the University of Cincinnati’s Masters in Community Planning Program as part of their second year planning workshop. -

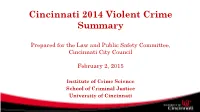

Cincinnati 2014 Violent Crime Summary

Cincinnati 2014 Violent Crime Summary Prepared for the Law and Public Safety Committee, Cincinnati City Council February 2, 2015 Institute of Crime Science School of Criminal Justice University of Cincinnati Part I Violent Crime Summary •Homicide •Robbery •Aggravated Assault •Rape Cincinnati Part I Violent Crime January 1 - December 31 4500 3951 4000 3844 3824 3604 3500 3433 3371 -40.5% 2965 3000 2809 2649 2500 2352 2000 1500 1000 500 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Part I Violent Crime in Cincinnati January 1 – December 31 Part I Violent Crime Short-term Trends 2013-2014 2013 2014 % Change Change 2649 2352 -297 -11.2% Long-term Trends 3-Year Avg. % Change 2014 5-Year Avg. % Change 2014 (2011-2013) vs. 3-Year (2009-2013) vs. 5-Year 2807.7 -16.2% 3079.6 -23.6% Homicides and Fatal and Nonfatal Shootings Cincinnati Homicide Totals January 1 – December 31 100 89 90 80 80 75 72 74 68 70 68 63 60 60 53 50 40 30 20 10 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Cincinnati Group/Gang Member Involved (GMI) Homicides January 1 – December 31 80 70 60 56 50 47 48 49 43 39 40 37 36 30 33 30 20 10 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Cincinnati Fatal and Non-Fatal Shootings January 1 – December 31 550 510 500 487 450 432 436 420 418 430 400 383 377 361 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Cincinnati Fatal and Non-Fatal Shootings January 1 – December 31 550 510 500 487 450 432 430 400 420 418 436 383 377 350 361 300 250 200 150 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 YTD Shooting Totals Avg. -

Police-Community Relations in Cincinnati: Year Three Evaluation Report

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Safety and Justice Program View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. -

2014 Annual Meeting

The Changing Landscape Of Homicide: Proceedings of the 2014 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group The Changing Landscape Of Homicide: Proceedings of the 2014 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group San Antonio, Texas Editors Dr. Lin Huff-Corzine University of Central Florida Dr. Hollianne Marshall University of California, Fresno Ashton Boston University of Central Florida Homicide Research Working Group Goals The Homicide Research Working Group (HRWG) is an international and interdisciplinary organization of volunteers dedicated to cooperation among researchers and practitioners who are trying to understand and limit lethal violence. The HRWG has the following goals: ♦ to forge links between research, epidemiology and practical programs to reduce levels of mortality from violence; ♦ to promote improved data quality and the linking of diverse homicide data sources; ♦ to foster collaborative, interdisciplinary research on lethal and non-lethal violence; ♦ to encourage more efficient sharing of techniques for measuring and analyzing homicide; ♦ to create and maintain a communication network among those collecting, maintaining and analyzing homicide data sets; and ♦ to generate a stronger working relationship among homicide researchers. Homicide Research Working Group publications include the Proceedings of each annual Intensive Workshop (beginning in 1991) and the journal, Homicide Studies, (beginning in 1997). More information is available on the HRWG web site at http://www.homicideresearchworkinggroup.org/ Suggested citation: Lin Huff-Corzine, Hollianne Marshall, and Ashton Boston (Eds.) (2014). The Changing Landscape of Homicide: Proceedings of the 2014 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group. San Antonio, TX: University of Central Florida. The views expressed in the Proceedings are those of the authors and speakers, and not necessarily those of the Homicide Research Working Group or the co-editors of this volume.