Polynesian Influences in New Zealand Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itin 12 out of Print 1 Histories & Anthologies

ITINERARY n.12 NOT ON MAP 15 4 7 8 9 12 13 1 2 3 5 6 10 11 14 With the nights lengthening, we present some alternatives to an evening by the tellie - local architectural history books. Future BLOCK guides will look at Kiwi architecture journals and monographs on local architects. 1 1940 Out-of-Print 1: Histories & Anthologies Paul Pascoe ‘Houses’, Making New Looking over the books on the history of New Zealand architecture, perhaps the most surprising Zealand Vol. 2, No. 20 thing is how few of them there are. Our Institute of Architects recently celebrated its centenary, but Dept of Int’l Affairs, Wellington one hundred years of professional activity have produced only a half-dozen major history books and a comparable number of minor ones. Even through the overall number of texts is small, expansion in the field is nonetheless noticeable from the 1970s. This followed, and was also concurrent with, the comprehensive redevelopment of our inner-cities, which involved the large-scale demolition of historic buildings to make way for new highrises. Public support for the retention of significant historic buildings meant the expansion of the heritage conservation sector, which led to an increase in research and writing on the country’s old buildings. In the latter 1970s and the 1980s, the rise of postmodernism encouraged further interest in architectural history; to make historical references in their buildings, architects had to know something about history. The 1990s saw renewed enthusiasm for the clean lines of modernism. This is evident not only in our buildings but also in the architectural history books and papers produced that decade. -

Itin 21 out of Print 3 Journals

ITINERARY n.21 NOT ON MAP 11 1 3 4 6 12 14 15 16 2 587 9 13 Sources: When Architecture NZ commissioned a series 10 of articles to mark the NZIA centenary in 2005, the first cab off the rank was New Zealand’s architecture “journals, magazines, bulletins and squibs” (January, pp. 69-85). Douglas Lloyd Jenkins provided the historical overview and others, including past editors, reflected on specific journals. 1905-1979 Out-of-Print 3: Journals 1 In World Architects in their Twenties, a book of interviews with international big-shots such as Renzo Progress Building & Allied Trades Piano, Jean Nouvel and Frank Gehry, each architect spoke about their education and early years in the Auckland profession. Asked if they had any advice for young architects, they all commented that youngsters should be wary of the architectural media; Renzo Piano went so far as to say “I think too much information’s like a drug … a very bad drug … So I have a suggestion: don’t buy any more … architecture magazines.” Such an attitude is surprising – and perhaps ingenuous – from those whose rise in the profession has relied on the support of such journals. Magazines, it seems, are paradoxically necessary but unhelpful. The internet is altering the way we receive information, but we in NZ have been heavily reliant on international journals to keep up with overseas developments. What, then, is the place of local journals in our smaller architectural culture? Our nation’s production of architectural books has been intermittent and uneven, and as a result local magazines have formed our primary historical record. -

Architecture Student Congresses in Australia, New Zealand and PNG from 1963-2011

Architecture Student Congresses in Australia, New Zealand and PNG from 1963-2011 Prologue Contents This book is the hurried result of research gathered 1960/61 Sydney over the last few weeks (and in a way the last few years, and decades), which sets out to remind stu- 1963 Auckland dents who are attending Flux, in Adelaide in 2011, 1964 Melbourne that student-led Congress has a long and marvel- lously incohesive (and sometimes incoherent) history 1965 Sydney in Australasia. 1966 Perth It dates back – at least we think – to 1963, when some New Zealand students invited Aldo van Eyck to Auck- 1967 Brisbane land to talk about the Social Aspects of New Housing. 1968 Hobart An organised mass gathering of architecture students has happened somewhere around New Zealand or 1969 Adelaide Australia at least thirty times since. 1970 Singapore Sydney This modest & messy booklet is the start of a larger project to more coherently collect and productively re- 1971 Auckland-Warkworth flect on the residue of Congress in Australasia. We 1972/73 Sunbury & Nimbin hope you enjoy it as much as we have. 1974 Brisbane to Munduberra The Spruik 1975 Lae, PNG A History of Activism: Student Congress 1963-2011 1976 Canberra Streamed Session, Friday Morning. 1977 Sydney As way of discussing the Congress, and imparting some of our knowledge about student organisations, 1979 Brisbane we will be hosting a session on Friday morning. 1981 Canberra The presentation will act as a catalyst for a Workshop 1983 Auckland addressing student-led organisations and events, with particular emphasis on the future design and im- 1985 Perth plementation of student Congress. -

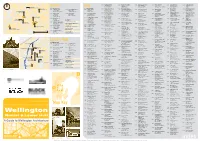

A Guide to Wellington Architecture

1908 Tramways Building 1928 Evening Post Building 1942 Former State Insurance 1979 Freyburg Building 1987 Leadenhall House 1999 Summit Apartments 1 Thorndon Quay 82 Willis St Office Building 2 Aitken St 234 Wakefield St 182 Molesworth St 143 Lambton Quay Futuna Chapel John Campbell 100 William Fielding 36 MOW under Peter Sheppard Craig Craig Moller 188 Jasmax 86 5 Gummer & Ford 60 Hoogerbrug & Scott Architects by completion date by completion date 92 6 St Mary’s Church 1909 Harbour Board Shed 21 1928 Former Public Toilets 1987 Museum Hotel 2000 VUW Adam Art Gallery Frederick de Jersey Clere 1911 St Mary’s Church 2002 Karori Swimming Pool 1863 Spinks Cottage 28 Waterloo Quay (converted to restaurant) 1947 City Council Building 1979 Willis St Village 90 Cable St Kelburn Campus 170 Karori Rd 22 Donald St 176 Willis St James Marchbanks 110 Kent & Cambridge Terraces 101 Wakefield St 142-148 Willis St Geoff Richards 187 Athfield Architects 8 Karori Shopping Centre Frederick de Jersey Clere 6 Hunt Davis Tennent 7 William Spinks 27 City Engineer’s Department 199 Fearn Page & Haughton 177 Roger Walker 30 King & Dawson 4 1909 Public Trust Building 1987 VUW Murphy Building 2000 Westpac Trust Stadium 1960 Futuna Chapel 2005 Karori Library 1866 Old St Paul's Church 131-135 Lambton Quay 1928 Kirkcaldie & Stains 1947 Dixon St Flats 1980 Court of Appeal & Overbridge 147 Waterloo Quay 62 Friend St 247 Karori Rd 34-42 Mulgrave St John Campbell 116 Refurbishments 134 Dixon St cnr Molesworth & Aitken Sts Kelburn Campus Warren & Mahoney Hoogerbrug Warren -

JULIA GATLEY Architects Contents

Athfield Architects JULIA GATLEY Contents Preface Encounters with Athfield vii // Formative Years Christchurch and Beyond 1 From Student Projects to the Athfield House 10 // Happenings Early Athfield Architects 35 From Imrie to Eureka 48 // Boom Corporates, Developers and Risk 117 From Crown House to Landmark Tower 128 // Public Works Architecture and the City 187 From Civic Square to Rebuilding Christchurch 204 Past and Present Staff 294 Glossary 296 References 297 Select Bibliography 301 Index 302 uck and timing are often important in the development of observation about one so young and Athfield barely gave a thought architects’ careers.1 Ian Athfield was fortunate to spend time to any other possible career paths. Ashby also saw in Tony a potential in New Zealand’s three biggest cities at crucial periods in career in music.5 Ella took particular heed and prompted both her sons his formative years. Born in Christchurch in 1940, he grew to follow the teacher’s suggestions. Athfield soon took the initiative, Lup there and became interested in architecture just as that city’s convincing Tony that they should build a garage at the family home,6 young Brutalists – the so-called Christchurch School – were having surely an eye-opener for any young person interested in architecture. an impact on the urban fabric. He studied in Auckland in the early Len and Ella also encouraged both boys to learn music. They played in 1960s, when influential nationalist and regionalist protagonists a band together in their early teens. The collaboration did not last, but were teaching in the School of Architecture and the Dutch architect Tony progressed through a series of musical groups – Max Merritt and 1 Andrew Barrie, ‘Luck and Timing in Post-War Japanese Aldo van Eyck visited New Zealand to deliver inspirational lectures. -

The Centre for Building Performance Research and the School Of

McCARTHY | "... ponderously pedantic pediments prevail ... good, clean fun in a bad, dirty world": New Zealand architecture in the 1980s AHA: Architectural History Aotearoa (2009) vol 6:1-11 "... ponderously pedantic pediments prevail ... good, clean fun in a bad, dirty world": New Zealand Architecture in the 1980s Christine McCarthy "A full year has now passed since NZ Architect Post (now an SOE) closed 432 post offices, and the Aotea Centre in Auckland,4 the committed itself ... to a programme of regular and the selling of state assets to private interests destruction of William Pitt's His Majesty's concerted architectural criticism." 5 "A criticism is no more than a personal viewpoint. It is was put in train. In 1989 GST increased to Theatre, and finally the National Museum of not gospel. The critic, too, is open to criticism, and 12.5% and the Serious Fraud Office was New Zealand, known these days as Te Papa.6 therein lies the challenge."1 established. Controversies included protests against the recurring lack of open competitions for major The 1980s in New Zealand started with Robert It was also a decade of drama in New Zealand public buildings, as well as the dominant Muldoon as Prime Minister: "Think Big," the architecture. Significant controversies arose disregard for architectural heritage. Springbok Tour, the price freeze, and the over buildings being built or being establishment of Kōhanga Reo. These demolished, the economies of land value and Competitions which did occur were usually at conflicting messages of expansion, building -

Roger Walker 1: Civic & Commercial

ITINERARY n.4344 11 3 8 6 10 9 4 1 2 5 7 13 12 This is the first of series of itineraries on the work of Roger Walker. Later itineraries will look at his houses and his collective housing projects. Roger Walker 1: Civic & Commercial Biography: In the 1960s, New Zealand’s most exciting architecture emerged from Christchurch – Miles Warren, Peter Roger Neville Walker was born Beaven and a host of other talented architects turned the city into the architectural hothouse now referred to as in Hamilton on 21 December The Christchurch School. However, in the early 1970’s a series of shifts – the ebbing of confidence in modernist 1942. Much has been made of principles, and key Christchurch architects moving their focus to large commercial projects – the Christchurch his childhood construction efforts, School seemed to lose its urgency and Wellington took over as New Zealand’s architectural laboratory. At the particularly his wooden trucks and center of this scene were the young architects Ian Athfield and Roger Walker. the Fort Nyte play hut constructed The best remembered 1970s work of both architects is their extroverted houses, but both were also active from as a 10-year-old. Walker attended their earliest days in the public and commercial realms. Walker had moved to Wellington to work under Calder, Hamilton Boys High School; he Fowler & Styles, his early contributions including the Link Span buildings and a church in Tauramanui, both wanted to design cars but his high indicating what was to come. With a few years he had completed The Wellington Club, a colorful cluster of low- school career advisor suggested rise forms that stood out among the high-rise offices of The Terrace. -

Summer 2014, Volume 4, Issue 4

. Poetry Notes Summer 2014 Volume 4, Issue 4 ISSN 1179-7681 Quarterly Newsletter of PANZA arising out of a “lack of any vital Inside this Issue Welcome relation to experience” (for references see the index to his Look Back Harder, Hello and welcome to issue 16 of 1987), still spring most readily to mind Welcome Poetry Notes, the newsletter of PANZA, – despite the partial rehabilitation in 1 the newly formed Poetry Archive of Trixie Te Arama Menzies’s article Comment on Kowhai Gold New Zealand Aotearoa. ‘Kowhai Gold – Skeleton or Scapegoat’, Poetry Notes will be published quarterly Landfall 165 (March 1988) pp.19-26, Obituary: Trevor Reeves and will include information about which demonstrated that the “poetic goings on at the Archive, articles on tradition” it embodies is not as isolated 3 historical New Zealand poets of interest, (a “continuum”: p.20) as has been Classic New Zealand occasional poems by invited poets and a poetry by Alice Mackenzie claimed, both from what preceded it 9 record of recently received donations to (Alexander and Currie) and what Comment on Yilma Tasew the Archive. followed (Curnow). 11 by Teresia Teaiwa Articles and poems are copyright in the This literary critical analysis of the book names of the individual authors. has overlooked and obscured its Comment on Lawrence The newsletter will be available for free bibliographical interest, which proves to 12 Inch download from the Poetry Archive’s be more than mere curiosity. website: Comparison of a number of copies Comment on Martin Wilson reveals that the anthology as planned 13 http://poetryarchivenz.wordpress.com included the work not of fifty-six poets but of fifty-seven: lurking in the index Comment on John and bibliography of a few of the earliest O’London Literary Club 14 Rowan Gibbs on copies off the press (and even in the text National Poetry Day poem of a single rogue specimen found) is Kowhai Gold “Geoffrey de Montalk”. -

Michael Dudding

(front cover) NEW ZEALAND ARCHITECTS ABROAD MICHAEL DUDDING (rear cover) NEW ZEALAND ARCHITECTS ABROAD MICHAEL DUDDING NEW ZEALAND ARCHITECTS ABROAD An Oral History Study of the experiences and motivations of New Zealand architects who undertook postgraduate studies in the United States during the immediate postwar period. by Michael Dudding A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy V I C T O R I A U N I V E R S I T Y O F W E L L I N G T O N 2 0 1 7 i ABSTRACT This thesis is an oral history based investigation of four recently graduated architects (Bill Alington, Maurice Smith, Bill Toomath and Harry Turbott) who individually left New Zealand to pursue postgraduate qualifications at United States universities in the immediate postwar period. Guided interviews were conducted to allow the architects to talk about these experiences within the broader context of their careers. The interviews probed their motivations for travelling and studying in the United States. Where possible archival material was also sought (Fulbright applications, university archives) for comparison with the spoken narratives. Although motivated by the search of modernity and the chance to meet the master architects of the period (Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Wright) what all gained was an increase in the confidence of their own abilities as architects (or as a landscape architect in the case of Turbott who switched his focus while in the United States). This increase in confidence partly came from realising that their architectural heroes were ordinary people. -

NZ Architecture in the 1970S: a One Day Symposium

"all the appearances of being innovative": NZ architecture in the 1970s: a one day symposium Date: Friday 2nd December 2016 Venue: School of Architecture/Te W āhanga Waihanga [please note due to building work, the symposium may be held on the Kelburn campus at VUW, more details closer to the date]. Victoria University/Te Whare W ānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a M āui, Wellington Convener: Christine McCarthy ([email protected]) Mike Austin's seemingly faint praise, in a 1974 review of a medium-density housing development, that the architecture had "all the appearances of being innovative," is echoed in Douglas lloyd Jenkins' observation that: "Although the 1970s projected an aura of pioneering individualism, the image disguised a high degree of conformity." The decade's anxious commencement, with the imminent threat of the European Economic Community (EEC) undermining our economic relationship with Mother Britain, was perhaps symptomatic of a risqué appearance being only skin deep. Our historic access to Britain's market to sell butter and cheese was eventually secured in the Luxembourg agreement, which temporarily retained New Zealand trade, but with reducing quotas, as a mechanism to gradually wean New Zealand's financial dependency on exports to Britain. As Smith observes: "Many older better-off Pakeha New Zealanders considered as betrayal Britain's entry in January 1973 to the EEC." The same year we joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As if in response, in architecture, colonial references were both recouped and abused, though lloyd Jenkins also credits the wider Victorian revival, dating from the mid-1960s, to its co- incidence with "a period in which most New Zealand towns and cities began to celebrate their centenaries." Peter Beaven's Chateau Commodore Hotel (Christchurch, 1972-73), as an example, alluded to Stokesay Castle (Shropshire, 1285) and a thirteenth-century barn (Cherwill, Wiltshire), resulting in a "playful .. -

Wellington Harbour Board Historic Area (Volume I)

New Zealand Historic Places Trust Pouhere Taonga Registration Report for a Historic Area Wellington Harbour Board Historic Area (Volume I) Lambton Harbour from Mount Victoria, Wellington. (K. Astwood, NZHPT, January 2012) Barbara Fill and Karen Astwood Draft: last amended 5 April 2012 New Zealand Historic Places Trust © TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. IDENTIFICATION 4 1.1. Name of Area 4 1.2. Location Information 4 1.3. Current Legal Description 4 1.4. Physical Extent of Area Assessed for Registration 5 1.5. Identification Eligibility 5 1.6. Physical Eligibility as an Historic Area 5 2. SUPPORTING INFORMATION 6 2.1. Historical Description and Analysis 6 2.2. Physical Description and Analysis 16 2.3. Key Physical Dates 24 2.4. Construction Professionals 26 2.5. Construction Materials 28 2.6. Former Uses 28 2.7. Current Uses 29 2.8. Discussion of Sources 31 3. SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT 40 3.1. Section 23 (1) Assessment 40 4. OTHER INFORMATION 44 4.1. Associated NZHPT Registrations 44 4.2. Heritage Protection Measures 45 5. APPENDICES 49 5.1. Appendix 1: Visual Identification Aids 49 5.2. Appendix 2: Visual Aids to Historical Information 52 5.3. Appendix 3: Visual Aids to Physical Information 57 5.4. Appendix 4: Significance Assessment Information 61 Wellington Harbour Board Historic Area Vol I 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Wellington Harbour Board Historic Area comprises part of the inner reaches of Wellington Harbour, extending from Pipitea Wharf (now absorbed by the Thorndon Container Terminal) in the north, to Clyde Quay Wharf in the south. This area formed the core of the Wellington Harbour Board’s (WHB) activities. -

The Centre for Building Performance Research and the School Of

MARRIAGE | Chase Corp: Force or Farce? | AHA: Architectural History Aotearoa (2009) vol 6:33-50 Chase Corp: Force or Farce? Guy Marriage, School of Architecture, Victoria University, Wellington & Studio Pacific Architecture, Wellington ABSTRACT: During the 1980s, one company grew to symbolise New Zealand's unhealthy obsession with money. Chase Corporation appeared as the pinnacle of the New Zealand dream – tall buildings, high finance, the sky was the limit. At last we were joining the big time. The mantra "Greed is Good" was taken to heart in New Zealand, by architects, developers, and much of the public – at least in Auckland and Wellington. Glittering towers of mirrored glass appeared weekly in the press, promising to change the face of the city forever. The reality was different: poorly designed, badly built buildings were financed by shady deals, and heritage was destroyed casually, with little thought for the consequences. This paper will attempt to unravel some of the work undertaken by Chase Corp during the 1980s. Introduction amounts of that wealth from the pockets of Australia. Simply put, Chase's modus operandi No history of architecture in New Zealand in New Zealanders when both the share price was to buy cheap, run-down property in the the 1980s could be complete without an and the company crashed. Chase Corporation best location in the middle of town. Three key examination and explanation of the Chase built a large part of the corporate skylines that people were behind the company name: "The Corporation. Chase grew in the 1970s and we still see today in Auckland and driving force behind Chase was Colin folded in the '90s, but primarily came to Wellington, and yet today the Chase Reynolds, who was, and is today, highly- prominence in the 1980s.