JULIA GATLEY Architects Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story up to Now Architects, President (2014–16) of the by Bill Mckay

FREE Please take one. Issue One An offering of New Zealand Architecture and Design. — 2016 — 10. 14. 26. The diversity of New Class of ’15: the creative Innovative work by design- Zealand’s architecture and inspiring designs oriented companies is is highlighted in Future that received the highest showcased in the hosting Islands, the country’s architectural honours at space at the venue of the exhibition in the Biennale the 2015 New Zealand New Zealand architecture Architeturra 2016. Architecture Awards. exhibition in Venice. Joyful architecture Children playing on the roof of Amritsar, the Wellington house that was a career-long project of Sir Ian Athfield (1940– 2015), an outstanding figure in New Zealand architecture. More village than residence, Amritsar has captivated visitors for 40 years. One new fan is U.S. critic Alexandra Lange (see page 9). Photograph courtesy Athfield Architects. Our archipelago has been discovered by a succession cultural and spiritual importance around which of voyagers and explorers over the centuries but was dwellings were clustered. one of the last significant land masses to be peopled. As the Māori population increased and society The story Around 800 years ago, in the last thrust of human became more tribalised, strategic hillsides were expansion throughout the Pacific Ocean, expert nav- secured during periods of warfare by large-scale igators sailing sophisticated doubled-hulled vessels earthworks and palisades known as pā. The history landed in the southern reach of Polynesia (‘many of New Zealand architecture is not just one of arrival up to now islands’) and adapted their way of life to a colder, and the adaptation and evolution of building forms more temperate land. -

How the Canterbury Earthquake Sequence Led to a Departure from Concrete Technologies

A CHANGE OF SCENE: HOW THE CANTERBURY EARTHQUAKE SEQUENCE LED TO A DEPARTURE FROM CONCRETE TECHNOLOGIES Morten Gjerde 1 School of Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington, P.O. Box 600, Wellington, 6140, New Zealand Over time, nature can expose even the slightest weakness. This became very clear following a sequence of unexpected earthquakes that struck in Christchurch, New Zealand earlier this decade. At the time the quakes struck, research and development with concrete building technology Canterbury had gained an international reputation and contributed significantly to the region's development. Structural and architectural innovation helped make concrete the material of choice for new commercial buildings. The paper outlines some of the key architectural and structural innovations evident in the buildings of the city. The earthquake sequence exposed several shortcomings in the design, construction and maintenance of buildings, including to several buildings that represent key moments along the innovation pathway. Now that the rebuild is well under way it is becoming clear with every building that is completed that the city’s visual character will be significantly different. The emerging character appears to be developing around the global materials of steel and glass, with concrete no longer featuring in the ways it had. The paper discusses the background to this departure and how it signals the end of a productive period of innovation with this local material. Keywords: Christchurch earthquakes, performance, concrete, disaster, innovation INTRODUCTION Throughout its brief history of post-colonial settlement, and prior to the widespread losses arising from the 2010-12 seismic sequence, Christchurch had gained a well-deserved reputation for the quality of its built environment. -

Abstraction and Artifice | AHA: Architectural History Aotearoa (2009) Vol 6:68-77

SOUTHCOMBE | Abstraction and Artifice | AHA: Architectural History Aotearoa (2009) vol 6:68-77 Abstraction and Artifice Mark Southcombe, School of Architecture, Victoria University, Wellington ABSTRACT: This paper reflects on the architecture of the Wanganui Community Arts Centre 1989, and local, national and international contexts of its design and realisation. It documents and records the project and its history. It advances a reading of the project and its critical aspirations based on personal experience, documentation and the characteristics of the architecture. Finally, with reference to Jan Turnovsky's The Poetics of a Wall Projection implications of an architect writing history of architecture is reflected on. Making a book is like making Architecture; you have to relation to its physical, historical and cultural Terry Farrell, Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaki, know at least something about the intractability of contexts. Following Jan Turnovsky2 I will Michael Graves, Charles Moore and Stanley concrete things1 adopt as method the idea that architecture has Tigerman, came to us through the periodicals an empirical objective reality that contains such as Architectural Design (AD) with its It is sobering when an annual history traces of related conceptual material that may issues: Post Modern Classicism of 1980, symposium covers a period that is close, a be critically discerned, interpreted and Freestyle classicism 1982, Abstract period that we have directly experienced, in discussed directly from the work. I will representationalism 1983, Post modernisim which we have produced work. It invites examine the architecture in relation to its and Discontinuity in 1987. The post modern reflection on history and our own relationship contexts primarily to document these, and to fascination with surface was widely taken up to it as it unfolds. -

Itin 12 out of Print 1 Histories & Anthologies

ITINERARY n.12 NOT ON MAP 15 4 7 8 9 12 13 1 2 3 5 6 10 11 14 With the nights lengthening, we present some alternatives to an evening by the tellie - local architectural history books. Future BLOCK guides will look at Kiwi architecture journals and monographs on local architects. 1 1940 Out-of-Print 1: Histories & Anthologies Paul Pascoe ‘Houses’, Making New Looking over the books on the history of New Zealand architecture, perhaps the most surprising Zealand Vol. 2, No. 20 thing is how few of them there are. Our Institute of Architects recently celebrated its centenary, but Dept of Int’l Affairs, Wellington one hundred years of professional activity have produced only a half-dozen major history books and a comparable number of minor ones. Even through the overall number of texts is small, expansion in the field is nonetheless noticeable from the 1970s. This followed, and was also concurrent with, the comprehensive redevelopment of our inner-cities, which involved the large-scale demolition of historic buildings to make way for new highrises. Public support for the retention of significant historic buildings meant the expansion of the heritage conservation sector, which led to an increase in research and writing on the country’s old buildings. In the latter 1970s and the 1980s, the rise of postmodernism encouraged further interest in architectural history; to make historical references in their buildings, architects had to know something about history. The 1990s saw renewed enthusiasm for the clean lines of modernism. This is evident not only in our buildings but also in the architectural history books and papers produced that decade. -

402 Montreal Street, Christchurch

DISTRICT PLAN –LISTED HERITAGE PLACE HERITAGE ASSESSMENT – STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HERITAGE ITEM NUMBER 391 DWELLING AND SETTING– 402 MONTREAL STREET, CHRISTCHURCH PHOTOGRAPH: M. VAIR-PIOVA, 2014 HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE Historical and social values that demonstrate or are associated with: a particular person, group, organisation, institution, event, phase or activity; the continuity and/or change of a phase or activity; social, historical, traditional, economic, political or other patterns. The dwelling at 402 Montreal Street has historical and social significance for its connection to Reverend John Aldred and Joseph Colborne Veel. The dwelling was built in 1878 when builder Henry Haggerty leased the property from the Rev. John Aldred and raised a mortgage to build on the site. Rev. Aldred, after whom Beveridge Street was once named, was an ordained Wesleyan minister, had arrived in New Zealand in 1840. He settled in Christchurch in 1854 as one of the first Wesleyan clergyman in the town and was granted land in Durham Street North by the Superintendent in 1856. Aldred was sent to Dunedin in 1864 but he later returned to live in St Albans. Haggerty encountered financial difficulties and sold the property to Dan Griffiths in 1882. Griffiths owned it for 10 years before Joseph Colborne Veel purchased part of the property in a mortgagee sale. Oxford-educated, Veel arrived in New Zealand in 1857, where he joined Page 1 the staff of The Press and subsequently became editor, a position he held until 1878. Veel also served on the Canterbury College Board of Governors and was secretary to the North Canterbury Education Board. -

2�18 2�18 Contents Contents

2�18 2�18 CONTENTS CONTENTS 6 ABOUT THE AWARDS 7 FROM THE JURY CONVENOR Published by the New Zealand Institute of Architects 12 Madden Street, Auckland NAMED AWARDS www.nzia.co.nz 8 November 2018 Editors John Walsh & Michael Barrett NEW ZEALAND ARCHITECTURE AWARDS Design 16 Carolyn Lewis Print CMYK, Hamilton © New Zealand Institute of Architects 30 JURORS AND AWARDS CRITERIA About the Awards From the jury convenor Each year since 1927, high quality architecture from across New Zealand has been Architecture is building, with love added. We saw this throughout recognised in the New Zealand Institute of Architects’ regional and national awards the awards programme from clients, who opened their homes programmes. Since 1997, the awards have been proudly supported by Resene. and important places, domestic and civic, to us; from an The point of the peer-reviewed New Zealand Architecture Awards is to encourage engineer, who spoke of battles waged in the name of dimensional architects to produce excellent work that benefits their clients and communities. tolerance; and from stories of builders, assisted only by a boy, The buildings in this booklet, all designed by NZIA architects, have been a dog and a ute, going extra miles and miles. awarded New Zealand Architecture Awards. As such, they can be considered the And the architects, of course, whom we celebrate. If the year’s best buildings. definition of a professional is one who works harder (way harder) At both regional and national levels, architecture awards can be conferred for than they are paid, then the architects who reached the New Commercial, Interior, Public and Small Project Architecture, Housing (including Zealand Awards level truly exhibit exemplary professionalism. -

Words That Make Worlds. Arguments That Change Minds. Ideas That Illuminate. We Publish Books That Make a Difference

AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY PRESS — 2012 CATALOGUE Words that make worlds. Arguments that change minds. Ideas that illuminate. We publish books that make a difference. Summer 2012 BA: AN INSIDER’S GUIDE Rebecca Jury BA: An Insider’s Guide is the essential book for all those considering study or about to embark on their arts degree. In 10 steps, Jury introduces readers to everything from choosing courses (just like putting together a personalised gourmet sandwich), setting up a study space and doing part-time work to turning up at lectures and tutorials and actually reading readings. In particular, she focuses on planning, work–life balance, study habits, succeeding at essays and exams and sorting out a life afterwards. Recently emerged from the maelstrom of university, Jury offers the inside word on doing well there. Rebecca Jury graduated with a BA (English and Mass Communication) from Canterbury University in 2008. Her grade average was excellent! Since completing her degree she has worked as a university tutor, a youth counsellor and a high-school teacher. February 2012, 190 x 140 mm, 200 pages Paperback, 978 1 86940 577 9, $29.99 2/3 Summer 2012 BEAUTIES OF THE OCTAGONAL POOL Gregory O’Brien In an eight-armed embrace, Beauties of the Octagonal Pool collects poems written from and out of a variety of times, locations and experiences. O’Brien’s poems have a thoughtful musicality, a shambling romance, a sense of humour, an eye on the horizon. On Raoul Island we meet a mechanical rat; on Waiheke, the horses of memory thunder down the course; and in Doubtful Sound, the first guitar music heard in New Zealand spills over the waves . -

Peter Beaven 1

ITINERARY n.24 NOT ON MAP 2 3 5 6 9 13 10 4 11 8 7 12 1 : Stephen Goodenough Photo This itinerary looks at Peter Beaven’s architecture before his hiatus in London in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A forthcoming itinerary will look at the work he has completed since his return to NZ. Biography: Peter Beaven 1: The 60s & 70s Peter Jamieson Beaven was In 1972 an exhibition entitled “The New Romantics in Building” was held at the Dowse Gallery in Lower born in Christchurch on 13 Hutt, including work by Ian Athfield, Roger Walker, Peter Beavan, Claude Megson and John Scott. The August 1925. He attended show celebrated one of the high points of 20th century Kiwi architecture, as a cohort of designers spliced Christ’s College, deciding local and international influences with such audacity that it seemed, if only briefly, that the nation could to become an architect after host a globally significant stream of architectural development. Peter Beaven was one of the senior a conversation with Paul members of this group (he’s seventeen years older than Walker), but he had rapidly made the transition Pascoe. He studied at the from a more orthodox modernism to the adventurous, hippy-fied approach of the youngsters. Such School of Architecture at the slipping in and out of both the Kiwi and international mainstreams has been the hallmark of Beaven’s University of Auckland, his career. studies being interrupted by Beaven established his office in the mid-1950s and his early work sits comfortably within the restrained, war service in the NZ Navy. -

Itin 21 out of Print 3 Journals

ITINERARY n.21 NOT ON MAP 11 1 3 4 6 12 14 15 16 2 587 9 13 Sources: When Architecture NZ commissioned a series 10 of articles to mark the NZIA centenary in 2005, the first cab off the rank was New Zealand’s architecture “journals, magazines, bulletins and squibs” (January, pp. 69-85). Douglas Lloyd Jenkins provided the historical overview and others, including past editors, reflected on specific journals. 1905-1979 Out-of-Print 3: Journals 1 In World Architects in their Twenties, a book of interviews with international big-shots such as Renzo Progress Building & Allied Trades Piano, Jean Nouvel and Frank Gehry, each architect spoke about their education and early years in the Auckland profession. Asked if they had any advice for young architects, they all commented that youngsters should be wary of the architectural media; Renzo Piano went so far as to say “I think too much information’s like a drug … a very bad drug … So I have a suggestion: don’t buy any more … architecture magazines.” Such an attitude is surprising – and perhaps ingenuous – from those whose rise in the profession has relied on the support of such journals. Magazines, it seems, are paradoxically necessary but unhelpful. The internet is altering the way we receive information, but we in NZ have been heavily reliant on international journals to keep up with overseas developments. What, then, is the place of local journals in our smaller architectural culture? Our nation’s production of architectural books has been intermittent and uneven, and as a result local magazines have formed our primary historical record. -

Architecture Student Congresses in Australia, New Zealand and PNG from 1963-2011

Architecture Student Congresses in Australia, New Zealand and PNG from 1963-2011 Prologue Contents This book is the hurried result of research gathered 1960/61 Sydney over the last few weeks (and in a way the last few years, and decades), which sets out to remind stu- 1963 Auckland dents who are attending Flux, in Adelaide in 2011, 1964 Melbourne that student-led Congress has a long and marvel- lously incohesive (and sometimes incoherent) history 1965 Sydney in Australasia. 1966 Perth It dates back – at least we think – to 1963, when some New Zealand students invited Aldo van Eyck to Auck- 1967 Brisbane land to talk about the Social Aspects of New Housing. 1968 Hobart An organised mass gathering of architecture students has happened somewhere around New Zealand or 1969 Adelaide Australia at least thirty times since. 1970 Singapore Sydney This modest & messy booklet is the start of a larger project to more coherently collect and productively re- 1971 Auckland-Warkworth flect on the residue of Congress in Australasia. We 1972/73 Sunbury & Nimbin hope you enjoy it as much as we have. 1974 Brisbane to Munduberra The Spruik 1975 Lae, PNG A History of Activism: Student Congress 1963-2011 1976 Canberra Streamed Session, Friday Morning. 1977 Sydney As way of discussing the Congress, and imparting some of our knowledge about student organisations, 1979 Brisbane we will be hosting a session on Friday morning. 1981 Canberra The presentation will act as a catalyst for a Workshop 1983 Auckland addressing student-led organisations and events, with particular emphasis on the future design and im- 1985 Perth plementation of student Congress. -

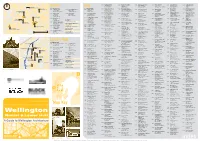

A Guide to Wellington Architecture

1908 Tramways Building 1928 Evening Post Building 1942 Former State Insurance 1979 Freyburg Building 1987 Leadenhall House 1999 Summit Apartments 1 Thorndon Quay 82 Willis St Office Building 2 Aitken St 234 Wakefield St 182 Molesworth St 143 Lambton Quay Futuna Chapel John Campbell 100 William Fielding 36 MOW under Peter Sheppard Craig Craig Moller 188 Jasmax 86 5 Gummer & Ford 60 Hoogerbrug & Scott Architects by completion date by completion date 92 6 St Mary’s Church 1909 Harbour Board Shed 21 1928 Former Public Toilets 1987 Museum Hotel 2000 VUW Adam Art Gallery Frederick de Jersey Clere 1911 St Mary’s Church 2002 Karori Swimming Pool 1863 Spinks Cottage 28 Waterloo Quay (converted to restaurant) 1947 City Council Building 1979 Willis St Village 90 Cable St Kelburn Campus 170 Karori Rd 22 Donald St 176 Willis St James Marchbanks 110 Kent & Cambridge Terraces 101 Wakefield St 142-148 Willis St Geoff Richards 187 Athfield Architects 8 Karori Shopping Centre Frederick de Jersey Clere 6 Hunt Davis Tennent 7 William Spinks 27 City Engineer’s Department 199 Fearn Page & Haughton 177 Roger Walker 30 King & Dawson 4 1909 Public Trust Building 1987 VUW Murphy Building 2000 Westpac Trust Stadium 1960 Futuna Chapel 2005 Karori Library 1866 Old St Paul's Church 131-135 Lambton Quay 1928 Kirkcaldie & Stains 1947 Dixon St Flats 1980 Court of Appeal & Overbridge 147 Waterloo Quay 62 Friend St 247 Karori Rd 34-42 Mulgrave St John Campbell 116 Refurbishments 134 Dixon St cnr Molesworth & Aitken Sts Kelburn Campus Warren & Mahoney Hoogerbrug Warren -

Roger Walker

Roger Walker New Zealand Institute of Architects Gold Medal 2016 Roger Walker New Zealand Institute of Architects Gold Medal 2016 B Published by the New Zealand Contents Institute of Architects 2017 Introduction 2 Editor: John Walsh Gold Medal Citation 4 In Conversation: Roger Walker with John Walsh 6 Contributors: Andrew Barrie, Terry Boon, Pip Cheshire, Comments Patrick Clifford, Tommy Honey, Gordon Andrew Barrie Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom 40 Moller and Gus Watt. Tommy Honey Who Dares Wins 42 Gordon Moller Fun, Roger-style 46 All plans and sketches © Roger Walker. Patrick Clifford Critical Architecture 50 Portrait of Roger Walker on page 3 by Gus Watt Reggie Perrin on Willis Street 52 Simon Wilson. Cartoon on page 62 Terry Boon A Radical Response 54 by Malcolm Walker. Pip Cheshire Ground Control to Roger Walker 58 Design: www.inhouse.nz Cartoon by Malcolm Walker 62 Printer: Everbest Printing Co. China © New Zealand Institute of Architects 2017 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-0-473-38089-2 1 The Gold Medal is the highest honour awarded by the New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA). It is given to an architect who, over the course of a career (thus far!), has designed a substantial body of outstanding work that is recognised as such by the architect’s peers. Gold Medals Introduction for career achievement have been awarded since 1999 and, collectively, the recipients constitute a group of the finest architects to have practised in New Zealand over the past half century.