NZ Architecture in the 1970S: a One Day Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story up to Now Architects, President (2014–16) of the by Bill Mckay

FREE Please take one. Issue One An offering of New Zealand Architecture and Design. — 2016 — 10. 14. 26. The diversity of New Class of ’15: the creative Innovative work by design- Zealand’s architecture and inspiring designs oriented companies is is highlighted in Future that received the highest showcased in the hosting Islands, the country’s architectural honours at space at the venue of the exhibition in the Biennale the 2015 New Zealand New Zealand architecture Architeturra 2016. Architecture Awards. exhibition in Venice. Joyful architecture Children playing on the roof of Amritsar, the Wellington house that was a career-long project of Sir Ian Athfield (1940– 2015), an outstanding figure in New Zealand architecture. More village than residence, Amritsar has captivated visitors for 40 years. One new fan is U.S. critic Alexandra Lange (see page 9). Photograph courtesy Athfield Architects. Our archipelago has been discovered by a succession cultural and spiritual importance around which of voyagers and explorers over the centuries but was dwellings were clustered. one of the last significant land masses to be peopled. As the Māori population increased and society The story Around 800 years ago, in the last thrust of human became more tribalised, strategic hillsides were expansion throughout the Pacific Ocean, expert nav- secured during periods of warfare by large-scale igators sailing sophisticated doubled-hulled vessels earthworks and palisades known as pā. The history landed in the southern reach of Polynesia (‘many of New Zealand architecture is not just one of arrival up to now islands’) and adapted their way of life to a colder, and the adaptation and evolution of building forms more temperate land. -

Theatre Royal Including All of That Part of the Building

CHRISTCHURCH CITY PLAN – LISTED HERITAGE PLACE HERITAGE ASSESSMENT – STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HERITAGE ITEM NUMBER 222 THEATRE ROYAL INCLUDING ALL OF THAT PART OF THE BUILDING SOUTH OF THE PROSCENIUM ARCH BUT EXCLUDING THE NEW PART OF THE BUILDING ON THE EASTERN SIDE OF THE SEISMIC WALL AND SETTING - 145 GLOUCESTER STREET, CHRISTCHURCH PHOTOGRAPH: M.VAIR-PIOVA, 5/12/2014 HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE Historical and social values that demonstrate or are associated with: a particular person, group, organisation, institution, event, phase or activity; the continuity and/or change of a phase or activity; social, historical, traditional, economic, political or other patterns. The Theatre Royal, including all of that part of the building south of the proscenium arch but excluding the new part of the building on the eastern side of the seismic wall, has high historical and social significance as an important performance venue in Christchurch for more than a century. The alterations to the building and its changes of use reflect the changing nature and fortunes of entertainment in the city over the last hundred years. The theatre was built for a syndicate headed by theatre impresario J. C. Williamson, and opened on 25 February 1908. The size of the building, originally seating 1,240, suggests the popularity of theatre at the time. The building is the third in Gloucester Street to carry the name. Williamson was an American who settled in Australia, founding his company in 1879; many of the better productions which toured Australasia from the late nineteenth until the mid-twentieth centuries travelled were through Williamson. -

Abstraction and Artifice | AHA: Architectural History Aotearoa (2009) Vol 6:68-77

SOUTHCOMBE | Abstraction and Artifice | AHA: Architectural History Aotearoa (2009) vol 6:68-77 Abstraction and Artifice Mark Southcombe, School of Architecture, Victoria University, Wellington ABSTRACT: This paper reflects on the architecture of the Wanganui Community Arts Centre 1989, and local, national and international contexts of its design and realisation. It documents and records the project and its history. It advances a reading of the project and its critical aspirations based on personal experience, documentation and the characteristics of the architecture. Finally, with reference to Jan Turnovsky's The Poetics of a Wall Projection implications of an architect writing history of architecture is reflected on. Making a book is like making Architecture; you have to relation to its physical, historical and cultural Terry Farrell, Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaki, know at least something about the intractability of contexts. Following Jan Turnovsky2 I will Michael Graves, Charles Moore and Stanley concrete things1 adopt as method the idea that architecture has Tigerman, came to us through the periodicals an empirical objective reality that contains such as Architectural Design (AD) with its It is sobering when an annual history traces of related conceptual material that may issues: Post Modern Classicism of 1980, symposium covers a period that is close, a be critically discerned, interpreted and Freestyle classicism 1982, Abstract period that we have directly experienced, in discussed directly from the work. I will representationalism 1983, Post modernisim which we have produced work. It invites examine the architecture in relation to its and Discontinuity in 1987. The post modern reflection on history and our own relationship contexts primarily to document these, and to fascination with surface was widely taken up to it as it unfolds. -

Itin 12 out of Print 1 Histories & Anthologies

ITINERARY n.12 NOT ON MAP 15 4 7 8 9 12 13 1 2 3 5 6 10 11 14 With the nights lengthening, we present some alternatives to an evening by the tellie - local architectural history books. Future BLOCK guides will look at Kiwi architecture journals and monographs on local architects. 1 1940 Out-of-Print 1: Histories & Anthologies Paul Pascoe ‘Houses’, Making New Looking over the books on the history of New Zealand architecture, perhaps the most surprising Zealand Vol. 2, No. 20 thing is how few of them there are. Our Institute of Architects recently celebrated its centenary, but Dept of Int’l Affairs, Wellington one hundred years of professional activity have produced only a half-dozen major history books and a comparable number of minor ones. Even through the overall number of texts is small, expansion in the field is nonetheless noticeable from the 1970s. This followed, and was also concurrent with, the comprehensive redevelopment of our inner-cities, which involved the large-scale demolition of historic buildings to make way for new highrises. Public support for the retention of significant historic buildings meant the expansion of the heritage conservation sector, which led to an increase in research and writing on the country’s old buildings. In the latter 1970s and the 1980s, the rise of postmodernism encouraged further interest in architectural history; to make historical references in their buildings, architects had to know something about history. The 1990s saw renewed enthusiasm for the clean lines of modernism. This is evident not only in our buildings but also in the architectural history books and papers produced that decade. -

2�18 2�18 Contents Contents

2�18 2�18 CONTENTS CONTENTS 6 ABOUT THE AWARDS 7 FROM THE JURY CONVENOR Published by the New Zealand Institute of Architects 12 Madden Street, Auckland NAMED AWARDS www.nzia.co.nz 8 November 2018 Editors John Walsh & Michael Barrett NEW ZEALAND ARCHITECTURE AWARDS Design 16 Carolyn Lewis Print CMYK, Hamilton © New Zealand Institute of Architects 30 JURORS AND AWARDS CRITERIA About the Awards From the jury convenor Each year since 1927, high quality architecture from across New Zealand has been Architecture is building, with love added. We saw this throughout recognised in the New Zealand Institute of Architects’ regional and national awards the awards programme from clients, who opened their homes programmes. Since 1997, the awards have been proudly supported by Resene. and important places, domestic and civic, to us; from an The point of the peer-reviewed New Zealand Architecture Awards is to encourage engineer, who spoke of battles waged in the name of dimensional architects to produce excellent work that benefits their clients and communities. tolerance; and from stories of builders, assisted only by a boy, The buildings in this booklet, all designed by NZIA architects, have been a dog and a ute, going extra miles and miles. awarded New Zealand Architecture Awards. As such, they can be considered the And the architects, of course, whom we celebrate. If the year’s best buildings. definition of a professional is one who works harder (way harder) At both regional and national levels, architecture awards can be conferred for than they are paid, then the architects who reached the New Commercial, Interior, Public and Small Project Architecture, Housing (including Zealand Awards level truly exhibit exemplary professionalism. -

No. Forty One January 1972 President: Miles Warren. Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw

COA No. Forty one January 1972 president: Miles Warren. Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw. Exhibitions Officer: Tony Geddes. news The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts Receptionist: Jill Goddard. News Editor: A. J. Bisley. 66 Gloucester Street Telephone 67-261 Registered at the Post Office Headquarters, Wellington, as a magazine P.O. Box 772 Christchurch Bill Cummings—Oil Marlborough Sounds Series—Kohanga - Marlborough Sounds. March Brian Holmewood and Subject to Adjustment Gallery Calendar Elizabeth Hancock Art School Drawings To 6 January Phillippa Blair National Safety Posters Carl Sydow To 12 January 10 Big Paintings Peter Mardon 6-20 January Manawatu Prints Frits Krijgsman 8-21 January Touring Reproductions April Susan Chaytor Early N.Z. Painting Tom Taylor 26 January Architects (Preview) British Paintings - 13 February Cranleigh Barton Exhibitions mounted with the assistance of the 14-29 February Philip Trusttum Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council through the 11-27 February Annual Autumn Exhibition agency of the Association of N.Z. Art Societies. PAGE ONE C. W. GROVER President's Comment Landscape Design I write this as your new, green as grass presi And Construction dent much aware of the series of distinguished and talented people who have run the Society in the past and wondering if I will be able to 81 Daniels Rd, Christchurch measure up to them. I am quickly beginning to Phone 527-702 appreciate what it means in time and involve ment. Fortunately the Society is in the expert hands of its famous Tweedle-dee and Tweedle dum, the secretary and the treasurer who kindly help the new boy and gently tell him what to do. -

Words That Make Worlds. Arguments That Change Minds. Ideas That Illuminate. We Publish Books That Make a Difference

AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY PRESS — 2012 CATALOGUE Words that make worlds. Arguments that change minds. Ideas that illuminate. We publish books that make a difference. Summer 2012 BA: AN INSIDER’S GUIDE Rebecca Jury BA: An Insider’s Guide is the essential book for all those considering study or about to embark on their arts degree. In 10 steps, Jury introduces readers to everything from choosing courses (just like putting together a personalised gourmet sandwich), setting up a study space and doing part-time work to turning up at lectures and tutorials and actually reading readings. In particular, she focuses on planning, work–life balance, study habits, succeeding at essays and exams and sorting out a life afterwards. Recently emerged from the maelstrom of university, Jury offers the inside word on doing well there. Rebecca Jury graduated with a BA (English and Mass Communication) from Canterbury University in 2008. Her grade average was excellent! Since completing her degree she has worked as a university tutor, a youth counsellor and a high-school teacher. February 2012, 190 x 140 mm, 200 pages Paperback, 978 1 86940 577 9, $29.99 2/3 Summer 2012 BEAUTIES OF THE OCTAGONAL POOL Gregory O’Brien In an eight-armed embrace, Beauties of the Octagonal Pool collects poems written from and out of a variety of times, locations and experiences. O’Brien’s poems have a thoughtful musicality, a shambling romance, a sense of humour, an eye on the horizon. On Raoul Island we meet a mechanical rat; on Waiheke, the horses of memory thunder down the course; and in Doubtful Sound, the first guitar music heard in New Zealand spills over the waves . -

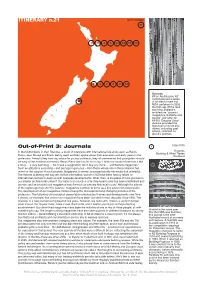

Itin 21 out of Print 3 Journals

ITINERARY n.21 NOT ON MAP 11 1 3 4 6 12 14 15 16 2 587 9 13 Sources: When Architecture NZ commissioned a series 10 of articles to mark the NZIA centenary in 2005, the first cab off the rank was New Zealand’s architecture “journals, magazines, bulletins and squibs” (January, pp. 69-85). Douglas Lloyd Jenkins provided the historical overview and others, including past editors, reflected on specific journals. 1905-1979 Out-of-Print 3: Journals 1 In World Architects in their Twenties, a book of interviews with international big-shots such as Renzo Progress Building & Allied Trades Piano, Jean Nouvel and Frank Gehry, each architect spoke about their education and early years in the Auckland profession. Asked if they had any advice for young architects, they all commented that youngsters should be wary of the architectural media; Renzo Piano went so far as to say “I think too much information’s like a drug … a very bad drug … So I have a suggestion: don’t buy any more … architecture magazines.” Such an attitude is surprising – and perhaps ingenuous – from those whose rise in the profession has relied on the support of such journals. Magazines, it seems, are paradoxically necessary but unhelpful. The internet is altering the way we receive information, but we in NZ have been heavily reliant on international journals to keep up with overseas developments. What, then, is the place of local journals in our smaller architectural culture? Our nation’s production of architectural books has been intermittent and uneven, and as a result local magazines have formed our primary historical record. -

Architecture Student Congresses in Australia, New Zealand and PNG from 1963-2011

Architecture Student Congresses in Australia, New Zealand and PNG from 1963-2011 Prologue Contents This book is the hurried result of research gathered 1960/61 Sydney over the last few weeks (and in a way the last few years, and decades), which sets out to remind stu- 1963 Auckland dents who are attending Flux, in Adelaide in 2011, 1964 Melbourne that student-led Congress has a long and marvel- lously incohesive (and sometimes incoherent) history 1965 Sydney in Australasia. 1966 Perth It dates back – at least we think – to 1963, when some New Zealand students invited Aldo van Eyck to Auck- 1967 Brisbane land to talk about the Social Aspects of New Housing. 1968 Hobart An organised mass gathering of architecture students has happened somewhere around New Zealand or 1969 Adelaide Australia at least thirty times since. 1970 Singapore Sydney This modest & messy booklet is the start of a larger project to more coherently collect and productively re- 1971 Auckland-Warkworth flect on the residue of Congress in Australasia. We 1972/73 Sunbury & Nimbin hope you enjoy it as much as we have. 1974 Brisbane to Munduberra The Spruik 1975 Lae, PNG A History of Activism: Student Congress 1963-2011 1976 Canberra Streamed Session, Friday Morning. 1977 Sydney As way of discussing the Congress, and imparting some of our knowledge about student organisations, 1979 Brisbane we will be hosting a session on Friday morning. 1981 Canberra The presentation will act as a catalyst for a Workshop 1983 Auckland addressing student-led organisations and events, with particular emphasis on the future design and im- 1985 Perth plementation of student Congress. -

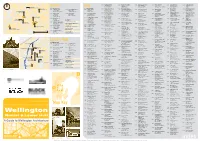

A Guide to Wellington Architecture

1908 Tramways Building 1928 Evening Post Building 1942 Former State Insurance 1979 Freyburg Building 1987 Leadenhall House 1999 Summit Apartments 1 Thorndon Quay 82 Willis St Office Building 2 Aitken St 234 Wakefield St 182 Molesworth St 143 Lambton Quay Futuna Chapel John Campbell 100 William Fielding 36 MOW under Peter Sheppard Craig Craig Moller 188 Jasmax 86 5 Gummer & Ford 60 Hoogerbrug & Scott Architects by completion date by completion date 92 6 St Mary’s Church 1909 Harbour Board Shed 21 1928 Former Public Toilets 1987 Museum Hotel 2000 VUW Adam Art Gallery Frederick de Jersey Clere 1911 St Mary’s Church 2002 Karori Swimming Pool 1863 Spinks Cottage 28 Waterloo Quay (converted to restaurant) 1947 City Council Building 1979 Willis St Village 90 Cable St Kelburn Campus 170 Karori Rd 22 Donald St 176 Willis St James Marchbanks 110 Kent & Cambridge Terraces 101 Wakefield St 142-148 Willis St Geoff Richards 187 Athfield Architects 8 Karori Shopping Centre Frederick de Jersey Clere 6 Hunt Davis Tennent 7 William Spinks 27 City Engineer’s Department 199 Fearn Page & Haughton 177 Roger Walker 30 King & Dawson 4 1909 Public Trust Building 1987 VUW Murphy Building 2000 Westpac Trust Stadium 1960 Futuna Chapel 2005 Karori Library 1866 Old St Paul's Church 131-135 Lambton Quay 1928 Kirkcaldie & Stains 1947 Dixon St Flats 1980 Court of Appeal & Overbridge 147 Waterloo Quay 62 Friend St 247 Karori Rd 34-42 Mulgrave St John Campbell 116 Refurbishments 134 Dixon St cnr Molesworth & Aitken Sts Kelburn Campus Warren & Mahoney Hoogerbrug Warren -

JULIA GATLEY Architects Contents

Athfield Architects JULIA GATLEY Contents Preface Encounters with Athfield vii // Formative Years Christchurch and Beyond 1 From Student Projects to the Athfield House 10 // Happenings Early Athfield Architects 35 From Imrie to Eureka 48 // Boom Corporates, Developers and Risk 117 From Crown House to Landmark Tower 128 // Public Works Architecture and the City 187 From Civic Square to Rebuilding Christchurch 204 Past and Present Staff 294 Glossary 296 References 297 Select Bibliography 301 Index 302 uck and timing are often important in the development of observation about one so young and Athfield barely gave a thought architects’ careers.1 Ian Athfield was fortunate to spend time to any other possible career paths. Ashby also saw in Tony a potential in New Zealand’s three biggest cities at crucial periods in career in music.5 Ella took particular heed and prompted both her sons his formative years. Born in Christchurch in 1940, he grew to follow the teacher’s suggestions. Athfield soon took the initiative, Lup there and became interested in architecture just as that city’s convincing Tony that they should build a garage at the family home,6 young Brutalists – the so-called Christchurch School – were having surely an eye-opener for any young person interested in architecture. an impact on the urban fabric. He studied in Auckland in the early Len and Ella also encouraged both boys to learn music. They played in 1960s, when influential nationalist and regionalist protagonists a band together in their early teens. The collaboration did not last, but were teaching in the School of Architecture and the Dutch architect Tony progressed through a series of musical groups – Max Merritt and 1 Andrew Barrie, ‘Luck and Timing in Post-War Japanese Aldo van Eyck visited New Zealand to deliver inspirational lectures. -

NEW ZEALAND Queenstown South Island Town Or SOUTH Paparoa Village Dunedin PACIFIC Invercargill OCEAN

6TH Ed TRAVEL GUIDE LEGEND North Island Area Maps AUCKLAND Motorway Tasman Sea Hamilton Rotorua National Road New Plymouth Main Road Napier NEW Palmerston North Other Road ZEALAND Nelson WELLINGTON 35 Route 2 Number Greymouth AUCKLAND City CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND Queenstown South Island Town or SOUTH Paparoa Village Dunedin PACIFIC Invercargill OCEAN Airport GUIDE TRAVEL Lake Taupo Main Dam or (Taupomoana) Waterway CONTENTS River Practical, informative and user-friendly, the Tongariro National 1. Introducing New Zealand National Park Globetrotter Travel Guide to New Zealand The Land • History in Brief Park Government and Economy • The People akara highlights the major places of interest, describing their Forest 2. Auckland, Northland ort Park principal attractions and offering sound suggestions and the Coromandel Mt Tongariro Peak on where to tour, stay, eat, shop and relax. Auckland City Sightseeing 1967 m Around Auckland • Northland ‘Lord of the The Coromandel Rings’ Film Site THE AUTHORS Town Plans 3. The Central North Island Motorway and Graeme Lay is a full-time writer whose recent books include Hamilton and the Waikato Slip Road Tauranga, Mount Maunganui and The Miss Tutti Frutti Contest, Inside the Cannibal Pot and the Bay of Plenty Coastline Wellington Main Road Rotorua • Taupo In Search of Paradise - Artists and Writers in the Colonial Tongariro National Park Seccombes Other Road South Pacific. He has been the Montana New Zealand Book The Whanganui River • The East Coast and Poverty Bay • Taranaki Pedestrian Awards Reviewer of the Year, and has three times been a CITY MALL 4. The Lower North Island Zone finalist in the Cathay Pacific Travel Writer of the Year Awards.