Scale Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISAB Food Web Review: Fish Production & Restoration

ISAB – Presentation to Columbia River Estuary Conference, Astoria, Oregon May 26, 2010 Independent Scientific Advisory Board for the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Columbia River Basin Indian Tribes, and National Marine Fisheries Service 851 SW 6th Avenue, Suite 1100 Portland, Oregon 97204 J. Richard Alldredge, Ph.D., Professor of Statistics at Washington State University. *David Beauchamp, Ph.D, Cooperative Fish Research Unit at U of Washington James Congleton, Ph.D., Emeritus Fisheries Professor, University of Idaho *Charles Henny, Ph.D., Emeritus Scientist, USGS Nancy Huntly, Ph.D., Professor of Wildlife Biology at Idaho State University. Roland Lamberson, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics and Director of Environmental Systems Graduate Program at Humboldt State University. Colin Levings, Ph.D., Scientist Emeritus and Sessional Researcher at Centre for Aquaculture and Environmental Research, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada. Robert J. Naiman, Ph.D., Professor of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences at U of Washington William Pearcy, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Oceanography at Oregon State University. Bruce Rieman, PhD, Research Scientist Emeritus, U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station *Greg Ruggerone, Ph.D., Fisheries Scientist for Natural Resources Consultants, Affiliated Research Scientist Alaska Salmon Program, U of Washington Dennis Scarnecchia, Ph. D., Professor of Fish and Wildlife Resources at University of Idaho. Peter Smouse, Ph.D., Professor of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources at Rutgers -

The Ecology of the Earth's Grazing Ecosystems

The Ecology of the Earth's Grazing Ecosystems Douglas A. Frank; Samuel J. McNaughton; Benjamin F. Tracy BioScience, Vol. 48, No. 7. (Jul., 1998), pp. 513-521. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0006-3568%28199807%2948%3A7%3C513%3ATEOTEG%3E2.0.CO%3B2-E BioScience is currently published by American Institute of Biological Sciences. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/aibs.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Oct 29 19:30:32 2007 The Ecology of the Earth's brazing Ecosystems Profound functional similarities exist between the Serengeti and Yellowstone Douglas A. -

Prof. Nancy Huntly Department of Biology, Utah State University, USA 11/05/2021, **16:00**, at Your Nearest Available Zoom Machine

Understanding biodiversity, from mountains and deserts to people and cancer Prof. Nancy Huntly Department of Biology, Utah State University, USA 11/05/2021, **16:00**, at your nearest available Zoom machine Professor Burt Kotler and I started our journeys as ecologists together, as graduate students with similar research interests and adjacent office cubicles, and have remained friends and colleagues. We share interests in consumer-resource interactions and community ecology, and this talk will focus on my research in those areas. Burt’s work has advanced understanding of biodiversity, with many contributions on coexistence of mammals, their predators, and their prey, including on what has been called “the ecology of fear”. His approach has leaned to behavior, especially foraging ecology, and communities, mine more to population biology and communities, and I will describe my thoughts on integrating those two views to better understand coexistence in our big and wildly variable world. I will talk about biodiversity through two primary lenses, the mechanistic one of coexistence theory and a more phenomenological one on how people have formed the world around them through large-scale environmental change and some unique behavior as foragers. I will consider especially how the variability of nature, in time and in space, can and does affect biodiversity. Because we are in part observing the impacts of Burt’s career in this seminar series, I will end with some description of how my approach to working as an ecologist has evolved over my career, in particular by more explicitly considering people into ecological models, as collaborators in and beneficiaries of ecological research, and, recently, as ecosystems within which the ecology of cancer plays out. -

Resource Pulses, Species Interactions, and Diversity Maintenance in Arid and Semi-Arid Environments

Oecologia (2004) 141: 236–253 DOI 10.1007/s00442-004-1551-1 PULSE EVENTS AND ARID ECOSYSTEMS Peter Chesson . Renate L. E. Gebauer . Susan Schwinning . Nancy Huntly . Kerstin Wiegand . Morgan S. K. Ernest . Anna Sher . Ariel Novoplansky . Jake F. Weltzin Resource pulses, species interactions, and diversity maintenance in arid and semi-arid environments Received: 1 August 2003 / Accepted: 5 March 2004 / Published online: 7 April 2004 # Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Arid environments are characterized by limited we discuss physiological, morphological, and life-history and variable rainfall that supplies resources in pulses. traits that facilitate plant survival and growth in strongly Resource pulsing is a special form of environmental water-limited variable environments, outlining how spe- variation, and the general theory of coexistence in variable cies differences in these traits may promote diversity. Our environments suggests specific mechanisms by which analysis emphasizes that the variability of pulsed environ- rainfall variability might contribute to the maintenance of ments does not reduce the importance of species high species diversity in arid ecosystems. In this review, interactions in structuring communities, but instead provides axes of ecological differentiation between species P. Chesson (*) that facilitate their coexistence. Pulses of rainfall also Section of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, influence higher trophic levels and entire food webs. Davis, CA 95616, USA Better understanding of how rainfall affects the diversity, e-mail: [email protected] species composition, and dynamics of arid environments Tel.: +1-530-7523698 Fax: +1-530-7521449 can contribute to solving environmental problems stem- ming from land use and global climate change. R. L. -

Hymenoptera: Apoidea), with an Emphasis on Perdita (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2018 Foraging Behavior, Taxonomy, and Morphology of Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea), with an Emphasis on Perdita (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae) Zachary M. Portman Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Portman, Zachary M., "Foraging Behavior, Taxonomy, and Morphology of Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea), with an Emphasis on Perdita (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae)" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7040. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7040 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORAGING BEHAVIOR, TAXONOMY, AND MORPHOLOGY OF BEES (HYMENOPTERA: APOIDEA), WITH AN EMPHASIS ON PERDITA (HYMENOPTERA: ANDRENIDAE) by Zachary M. Portman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Ecology Approved: _________________________ _________________________ Carol von Dohlen, Ph.D. Terry Griswold, Ph.D. Major Professor Project Advisor _________________________ _________________________ Nancy Huntly, Ph.D. Karen Kapheim, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _________________________ _________________________ Luis Gordillo, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Zachary M. Portman 2018 All Rights Reserved1 1 Several studies have been published previously and others remain to be submitted to peer-reviewed journals. As such, a disclaimer is necessary. -

Packet Materials for Dec 8-11, 2003 Council Meeting

JUDI DANIELSON TOM KARIER CHAIR VICE-CHAIR Idaho Washington Jim Kempton Frank L. Cassidy Jr. Idaho "Larry" Washington Gene Derfler Oregon Ed Bartlett Montana Melinda S. Eden kOregon John Hines Montana Steve Crow Executive Director December 2, 2003 DECISION MEMORANDUM To: Council Members From: Erik Merrill and Steve Waste Subject: ISRP and ISAB Appointments Proposed Actions Council staff requests Council actions and discussion pertaining to Independent Scientific Review Panel (ISRP) and Independent Scientific Advisory Board (ISAB) member terms and appointments. Staff asks that the Council: 1) Appoint Dr. John Epifanio, Illinois Natural History Survey, as a member of the ISRP. 2) Approve extension of term limits for the current ISRP members through May 2005. 3) Initiate the process to rebuild the pool of potential ISRP and ISAB members for future appointments by reconvening the National Research Council nomination committee, and, with NOAA Fisheries and the Columbia River Indian Tribes, jointly sending a letter to the region requesting nominations for consideration by the NRC nomination committee. 4) Discuss ISAB member renewals and the appointment process for new ISAB members. The ISRP and ISAB have different responsibilities in the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program, and the Council plays distinct roles in the administration of each group. To avoid confusion between the groups, this memo addresses decisions and background information related to each group separately, first the ISRP and then the ISAB. Independent Scientific Review Panel Background The Independent Scientific Review Panel (ISRP) consists of eleven members assisted by a number of Peer Review Group (PRG) members. The ISRP was created by amendment to the Northwest Power Act in 1996. -

Curriculum Vitae – Charles Mitchell – 24 September 2021

Curriculum Vitae – Charles Mitchell – 24 September 2021 PERSONAL Dr. Charles E. Mitchell Department of Biology The University of North Carolina Chapel Hill NC 27599-3280 Email: [email protected]. http://bio.unc.edu/people/faculty/mitchell/ EDUCATION 1995-2001 Ph.D. in Ecology. University of Minnesota. Advisor: David Tilman. 1991-1995 B.S. in Biology and Spanish, Co-Major in Human and Natural Ecology. Emory University. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Primary appointment in the Department of Biology Secondary appointment in the Environment, Ecology, and Energy Program. Jan 2016 – present Professor. Jan 2011 – Dec 2015 Associate Professor. Jan 2005 – Dec 2010 Assistant Professor. Cornell University: 2001-2004 Postdoctoral Fellow / Associate with Alison G. “Sunny” Power. HONORS 2002-2004 NSF Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Microbial Biology. 1998-2000 Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation Graduate Fellowship from The Land Institute 1995-1998 University of Minnesota Graduate School Fellowship. 1991-1995 Emory University Duncan Scholarship (non-need-based, full tuition). 1991 National Merit Scholar. 1990 U.S. Department of Education Columbus Scholar (50 nationally). 1990 U.S. Department of Energy Environmental Science Scholar (Texas; 1 per state). BIBLIOGRAPHY Google Scholar: http://scholar.google.com/citations?user=wRUow4cAAAAJ. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1633-1993. ResearcherID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/I-3709-2014. Scopus Author ID: http://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.url?authorId=36548716300. Peer-reviewed journal articles: Underlining indicates student, technician, or postdoc under my mentorship. Ebeling, A., A.T. Strauss, and 34 additional authors including C.E. Mitchell, in press. Nutrient enrichment increases invertebrate herbivory and pathogen damage in grasslands. -

Urban Food Webs: Predators, Prey, and the People Who Feed Them

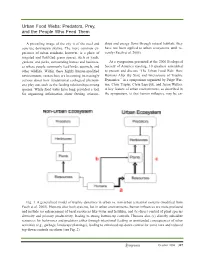

Urban Food Webs: Predators, Prey, and the People Who Feed Them A prevailing image of the city is of the steel and ships and energy flows through natural habitats, they concrete downtown skyline. The more common ex‑ have not been applied to urban ecosystems until re‑ perience of urban residents, however, is a place of cently (Faeth et al. 2005). irrigated and fertilized green spaces, such as yards, gardens, and parks, surrounding homes and business‑ At a symposium presented at the 2006 Ecological es where people commonly feed birds, squirrels, and Society of America meeting, 10 speakers assembled other wildlife. Within these highly human-modified to present and discuss “The Urban Food Web: How environments, researchers are becoming increasingly Humans Alter the State and Interactions of Trophic curious about how fundamental ecological phenom‑ Dynamics,” in a symposium organized by Paige War‑ ena play out, such as the feeding relationships among ren, Chris Tripler, Chris Lepczyk, and Jason Walker. species. While food webs have long provided a tool A key feature of urban environments, as described in for organizing information about feeding relation‑ the symposium, is that human influence may be en‑ Fig. 1. A generalized model of trophic dynamics in urban vs. non-urban terrestrial systems (modified from Faeth et al. 2005). Humans alter both systems, but in urban environments, human influences are more profound and include (a) enhancement of basal resources like water and fertilizer, and (b) direct control of plant species diversity and primary productivity, leading to strong bottom-up controls. Humans also (c) directly subsidize resources for herbivores and predators either through intentional feeding or unintended consequences of other activities (e.g., garbage, landscape plantings), leading to enhanced top-down control for some taxa and reduced top-down controls on others (see Fig. -

The Abiotic and Biotic Controls of Arctic Lake Food Webs: a Multifaceted Approach to Quantifying Trophic Structure and Function

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2018 The Abiotic and Biotic Controls of Arctic Lake Food Webs: A Multifaceted Approach to Quantifying Trophic Structure and Function Stephen L. Klobucar Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Klobucar, Stephen L., "The Abiotic and Biotic Controls of Arctic Lake Food Webs: A Multifaceted Approach to Quantifying Trophic Structure and Function" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7293. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7293 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ABIOTIC AND BIOTIC CONTROLS OF ARCTIC LAKE FOOD WEBS: A MULTIFACETED APPROACH TO QUANTIFYING TROPHIC STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION by Stephen L. Klobucar A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Aquatic Ecology Approved: ______________________ ______________________ Phaedra Budy, Ph.D. Jereme Gaeta, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ______________________ Nancy Huntly, Ph.D. Chris Luecke, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member ______________________ ______________________ Sarah Null, Ph.D. Laurens H. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Stephen Klobucar 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The abiotic and biotic controls of arctic lake food webs: A multifaceted approach to quantifying trophic structure and function by Stephen L. -

Conservation Biology for All

1 Conservation Biology for All EDITED BY: Navjot S. Sodhi Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore AND *Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University (*Address while the book was prepared) Paul R. Ehrlich Department of Biology, Stanford University 1 © Oxford University Press 2010. All rights reserved. For permissions please email: [email protected] Sodhi and Ehrlich: Conservation Biology for All. http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780199554249.do 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Oxford University Press 2010 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 Reprinted with corrections 2010 Available online with corrections, January 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Winter Meeting of the California Pika Consortium

WINTER MEETING OF THE CALIFORNIA PIKA CONSORTIUM UPDATES ON PIKAS IN THE SIERRA NEVADA, SOUTHERN CASCADES, AND GREAT BASIN Riverside Convention Center Riverside, CA February 11, 2011 Hosted by: US Forest Service – Pacific Southwest Research Station University of California, Berkeley California Department of Fish and Game The Wildlife Society – Western Section SUMMARY REPORT Prepared by: Scott Osborn (DFG) Deana Clifford (DFG) Randi Logsdon (DFG) Connie Millar (USFS) Toni Lyn Morelli (USFS) May 6, 2011 Contents Meeting Notes------------------------------ --------------------------------------------2 Meeting Evaluation Summary-------------- -------------------------------------------28 Agenda-------------------------------------- -------------------------------------------31 Prospectus----------------------------------- -------------------------------------------32 Facilitated Discussion Plan----------------- -------------------------------------------33 Cover photos by Constance I. Millar. Left to right: Virginia Lakes Canyon, CA; Buddy, Warren Fork, Lee Vining Canyon, CA; Pine Creek, Toquima Range, NV. 1 California Pika Consortium Winter Meeting February 11, 2011 – Riverside Convention Center Notes prepared by Scott Osborn, Deana Clifford, and Randi Logsdon Slide presentations are available for viewing on the CPC website at the 2011 Meeting Information page. Participants Andrew Smith Kim Fitts Brad Bauman Lindsay Cline Bob Roney Lyle Nichols Bob Westfall Mary Ellen Hannibal Connie Millar Mackenzie Jeffress Cody Massing Mary Peacock Chris -

Landscape Report, Review of Strategies for Recovering Restoration and How These Relate to the Criteria

Cover design by Melissa Shavlik, NWPCC Photos by Eric Loudenslager, Erik Merrill, and Kentaro Morita Independent Scientific Advisory Board for the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, Columbia River Basin Indian Tribes, and National Marine Fisheries Service 851 SW 6th Avenue, Suite 1100 Portland, Oregon 97204 Contributors ISAB and Ad Hoc Members J. Richard Alldredge, Ph.D., Emeritus Professor of Statistics at Washington State University Peter A. Bisson, Ph.D., Senior Scientist at the Olympia (Washington) Forestry Sciences Laboratory of the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station (ad hoc member) James Congleton, Ph.D., Idaho Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Professor, University of Idaho (retired) Nancy Huntly, Ph.D., Professor of Biology and Director of the Ecology Center, Utah State University Roland Lamberson, Ph.D., Emeritus Professor of Mathematics and Director of Environmental Systems Graduate Program at Humboldt State University Colin Levings, Ph.D., Scientist Emeritus at Centre for Aquaculture and Environmental Research, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, West Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Robert J. Naiman, Ph.D., Professor of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences at University of Washington William Pearcy, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus, College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University Bruce Rieman, Ph.D., Research Scientist Emeritus, U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station Greg Ruggerone, Ph.D., Fisheries Scientist for Natural Resources Consultants, Affiliated Research Scientist Alaska Salmon Program, University of Washington Dennis Scarnecchia, Ph. D., Professor of Fish and Wildlife Resources at University of Idaho Courtland Smith, Ph. D., Professor Emeritus, School of Language, Culture, and Society, Oregon State University (ad hoc member) Peter Smouse, Ph.D., Professor of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources at Rutgers University Chris C.