Right and Wrong, Balanced on the Edge of a Spear: U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II. -

The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): a Revolution in Organizational Structure

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations Student Scholarship 12-2020 The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure Adam Davis University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Infrastructure Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Nonprofit Administration and Management Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Adam, "The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure" (2020). Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations. 165. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones/165 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure Adam Davis Capstone paper for Master of Policy, Planning, and Management Program Muskie School of Public Service University of Southern Maine December 2020 Professor Joseph McDonnell, Capstone Advisor THE BRIGADE COMBAT TEAM (BCT) 2 Abstract This paper explores the U.S. Army’s force reorganization around the Brigade Combat Team (BCT), which began in 2002. The BCT shifted how various army units interacted by changing the echelon at which different types of units report to a single commander, essentially creating self-sufficient units of about 2,500 soldiers instead of the previous self-sufficient units of about 15,000 soldiers. -

U.S. ARMY: UNIT RECORDS, Sixth Engineer Special Brigade, 1944-1945

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: UNIT RECORDS, Sixth Engineer Special Brigade, 1944-1945 1,600 pages (approximate) Boxes 554-555b The 6th Engineer Special Brigade (ESB) was activated on January 20, 1944, and assigned to the U.S. 1st Army. Throughout the first half of that year the Brigade received reinforcements of men and additional support units. Until the invasion of Normandy, the reconstituted Brigade was involved in training operations in England. There were three Engineer Combat Battalions assigned to the 6th ESB: the 147th, 149th, and 203rd. Along with some supporting units, these battalions landed on Omaha Beach as part of the First Army on June 6, 1944. The remainder of the Brigade landed in follow-up waves throughout that month. After the initial assault on Normandy, the Brigade assisted in the expansion of the beachhead. Most duties for the three Combat Battalions consisted of scouting out and clearing minefields, while the supporting units for the Brigade were involved with the processing of prisoners, transportation of supplies and personnel, and other rear area functions. Records for the 6th ESB are scattered from January 1944 to May 1945, with a number of months being completely absent. Most of the documentation is concentrated between the months of June 1944 and November 1944. Because it was an Engineer unit the 6th ESB was frequently broken up, with it’s subordinate battalions and companies being detached to various units during and after the Normandy landings. The records are therefore made up mostly of these detached units, so they will not appear as part of an overall Brigade history. -

The U.S. Military's Force Structure: a Primer

CHAPTER 2 Department of the Army Overview when the service launched a “modularity” initiative, the The Department of the Army includes the Army’s active Army was organized for nearly a century around divisions component; the two parts of its reserve component, the (which involved fewer but larger formations, with 12,000 Army Reserve and the Army National Guard; and all to 18,000 soldiers apiece). During that period, units in federal civilians employed by the service. By number of Army divisions could be separated into ad hoc BCTs military personnel, the Department of the Army is the (typically, three BCTs per division), but those units were biggest of the military departments. It also has the largest generally not organized to operate independently at any operation and support (O&S) budget. The Army does command level below the division. (For a description of not have the largest total budget, however, because it the Army’s command levels, see Box 2-1.) In the current receives significantly less funding to develop and acquire structure, BCTs are permanently organized for indepen- weapon systems than the other military departments do. dent operations, and division headquarters exist to pro- vide command and control for operations that involve The Army is responsible for providing the bulk of U.S. multiple BCTs. ground combat forces. To that end, the service is orga- nized primarily around brigade combat teams (BCTs)— The Army is distinct not only for the number of ground large combined-arms formations that are designed to combat forces it can provide but also for the large num- contain 4,400 to 4,700 soldiers apiece and include infan- ber of armored vehicles in its inventory and for the wide try, artillery, engineering, and other types of units.1 The array of support units it contains. -

COL Tonri Corel Brown Brigade Commander U.S. Army Satellite Operations Brigade Chief Reserve Affairs Adviser, USASMDC

COL Tonri Corel Brown Brigade Commander U.S. Army Satellite Operations Brigade Chief Reserve Affairs Adviser, USASMDC COL Tonri Corel Brown, a native of Auburn, Alabama, was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Signal Corps through Alabama A&M University Army ROTC program. He holds a Bachelor of Science from Alabama A&M University, Master of Arts from Webster University and a Master of Strategic Studies from the U.S. Army War College. His service includes platoon leader, Cable Platoon and Extension Node Platoons, Delta Company, 63rd Signal Battalion, Fort Gordon, Georgia; platoon leader, Large Extension Nodal Platoon, and executive officer, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 63rd Signal Battalion, Fort Gordon; assistant battalion S-3 and telecommunication officer, 63rd Signal Battalion, Fort Gordon; battalion network officer and plans officer, 54th Signal Battalion (FWD), Camp Doha, Kuwait; battalion signal officer S-6, 2nd-325th Airborne Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, North Carolina; chief communications and electronic officer, G-6 96th Regional Readiness Command, Fort Douglas, Utah; enterprise operations officer, U.S. Army Reserve Command G-2/6, Fort McPherson, Georgia; signal force development officer, USARC Army Reserve Force Programs Directorate, Fort McPherson; student, Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; commandant, High Tech Regional Training Site-Maintenance, Sacramento, California; center commander, Brien Thomas Collins U.S. Army Reserve Center, Sacramento; deputy G-3/5, chief of operations, 335th Signal Command (Theater), East Point, Georgia; assistant chief of staff G-6, U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command (Airborne), Fort Bragg; student, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania; squadron commander, 4th Joint Communications Squadron, Joint Communications Support Element (Airborne), MacDill Air Force Base, Florida; chief reserve affairs adviser, U.S. -

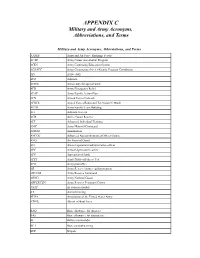

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Military Units Style Contents

Military Units Style - Colors Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Blue Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 1 Military Units Style - Fill Symbols Unknown Unknown, Pending 2 Friendly Hostile Hostile, S, J, Faker 2 Neutral 1 Neutral 3 Weather 3 Weather 4 Area Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 2 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols à Infantry Soldier  Helicopter - AH Apache Å Missile Launcher Æ Frigate Ê Generic Tank Ç Destroyer Ë Enemy Tank È Submarine SSBN Ì B-2 Stealth É Submarine Attack Ó F-14 Tomcat À Torpedo Ô Fighter ß Explosion Õ FA-18 ! Unit Ö F-5 " Headquarters Unit Ù Fighter # Logistics/Admin Installation Ú Fighter $ Theater Ü Generic Fighter % Corps Ò E-3 AWACS & Supply unit Ï Helicopter - CH-46 Chinook ' Squad Ð Helicopter - AH Cobra ( Section/Platoon Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. Located in: ArcGIS\Bin\Styles\Military Units.style All Rights Reserved. Version: ArcGIS 8.3 3 Military Units Style - Marker Symbols ) Platoon/Squadron 8 Infantry Battalion * Company/Battery/Troop 9 Infantry Regiment + Battalion/Squadron : Infantry Brigade , Regiment ; Infantry Division - Brigade < Infantry Corps . Division = Infantry Army / Corps > Infantry Mechanized Squad 0 Army ? Infantry Mechanized Section 1 Infantry @ Infantry Mechanized Platoon 2 Infantry Mechanized A Infantry Mechanized Company 3 Armor B Infantry Mechanized Battalion Company 4 Infantry Squad C Infantry Mechanized Regiment 5 Infantry Section D Infantry Mechanized Brigade 6 Infantry Platoon E Infantry Mechanized Division 7 Infantry Company F Infantry Mechanized Corps Copyright © 1999 - 2004 ESRI. -

20120319 Mg Rossmanith

Major General (DEU) Richard Rossmanith Chief of Staff Deployable Joint Staff Element 1 Major General Richard Rossmanith was born on March 16 th , 1955, and spent his youth in Bavaria. In July 1973 he joined the Bundeswehr, Light Infantry Battalion 561. In 1977 he graduated from the Bundeswehr University in Munich with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Electrical Engineering. From 1977 to 1981 he served as Platoon Commander in Light Infantry Battalion 112, Regen, before be- coming Company Commander in 2 nd and 4 th Company of Mechanized Infantry Battalion 112, also sta- tioned in Regen, from 1981 to 1985. Between 1985 and 1987 he attended the German Command and General Staff Officer Course in Ham- burg. After that he was appointed to his first NATO position as Desk Officer for Politico-Military Affairs to the German Military Representative to the Military Committee in Brussels, Belgium. In 1989 he became the G3 of Armoured Brigade 6 in Hofgeismar, Germany, and in 1990 he was sent to Erfurt to serve as Chief of Staff of 4 th Motorized Rifle Division (former National Peoples Army). In April 1991 he was assigned to his second NATO position as Branch Chief in Headquarters BALTAP, Karup, Denmark, and served there until 1993. Returning to Germany he was next posted to the Ministry of Defence, initially as Desk Officer in the Armed Forces Staff (Bundeswehr Operations), before becoming Deputy Branch Chief (Policy) and G3. From June 1995 to March 1997 he commanded Mechanized Infantry Battalion 212 in Augustdorf, Ger- many, followed by a deployment to SFOR, where he became the G3 of the German National Contingent in Rajlovac, Bosnia, in April 1997. -

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce The Armed Forces Officer THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. 2017 Published in the United States by National Defense University Press. Portions of this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record of this publication may be found at the Library of Congress. Book design by Jessica Craney, U.S. Government Printing Office, Creative Services Division Published by National Defense University Press 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64) Suite 2500 Fort Lesley J. McNair Washington, DC 20319 U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-16-093758-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Contents FOREWORD by General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., U.S. Marine Corps, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ...............................................................................ix PREFACE by Major General Frederick M. -

AR 600-20. Army Command Policy

Army Regulation 600 – 20 Personnel-General Army Command Policy Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 24 July 2020 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 600 – 20 Army Command Policy This administrative revision, dated 4 February 2021— o References DODD 1350.2 (para 6–9). o Removes appendix (app Q). This administrative revision, dated 1 September 2020— o Updates information (table 1–1). This administrative revision, dated 30 July 2020— o Updates information (fig 2–5). This major revision, dated 24 July 2020— o Adds reference to DoDI 1342.22 which now serves as the primary source of Family readiness policy guidance (title page). o Adds and/or updates responsibilities for the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Installations, Environment and Energy); Deputy Chief of Staff, G–9; Commanding General, U.S. Army Materiel Command; and the Commanding General, U.S. Army Installation Management Command (paras 1–4b, 1–4f, 2–5b, 5–2b, 7–5d). o Requires command leadership to treat Soldiers and Department of the Army Civilians with dignity and respect at all times (para 1–6c). o Clarifies the written abbreviation for the grade of “Specialist” (table 1 – 1, note 5). o Updates roles and responsibilities for command of installations (para 2–5b). o Clarifies policy on assumptions of command during the temporary absence of the commander (paras 2–9a(3), 2– 9d, 2 – 10, and 2 – 12). o Adds policy for command of installations, activities, and units on Joint bases (para 2 – 6). o Clarifies policy on the role of the reviewing commander regarding designation of junior in the same grade to command (para 2–8c). -

FM 3-101. Chemical Staffs and Units

FM 3-101 FM 3-101 ii FM 3-101 CHAPTER ONE CHEMICAL UNIT AND STAFF ORGANIZATIONS This chapter describes the organization and functioning of chemical units (brigade to team) and chemical staffs (theater army to battalion). The primary focus of this manual is warfighting, however chemical units and battle staffs may be employed in operations other than war (chapter 6) CHEMICAL UNITS The mission of chemical units is to provide decon, NBC reconnaissance, large-area smoke, and staff support to commanders to enhance their warfighting capabilities or support contingency requirements. Most chemical units are 100 percent mobile. Basis of allocation is determined on the number and type of units being supported and METT-T. Appendix A provides details of specific unit organization. CHEMICAL BRIGADE The chemical brigade normally supports a corps and consists of a brigade headquarters and headquarters company (HHC) and two to six chemical battalions. The brigade HHC consists of the brigade headquarters, containing the commander’s immediate staff (S 1, S2, S3, S4, and communications) and the headquarters company, which provides administrative and logistical support to the headquarters, 1-1 FM 3-101 The chemical brigade commander, with the advice of his staff and the corps chemical section, evaluates and determines the chemical unit support requirements for the corps. The brigade commander advises the corps commander concerning the employment of chemical assets, The brigade staff develops the scheme of support based on the NBC situation and METT-T. The brigade HHC is 50 percent mobile and provides its own organizational maintenance and mess support and establishes and operates internal and external radio and wire communications nets. -

Defense Primer: Department of the Army and Army Command Structure

Updated January 2, 2020 Defense Primer: Department of the Army and Army Command Structure Overview Senior Leadership Article I, Section 8, Clause 12 of the Constitution stipulates, The DA is headed by a civilian Secretary of the Army “The Congress shall have power ... to raise and support (SECARMY) who is appointed by the President with the Armies ... make rules for the government and regulation of advice and consent of the U.S. Senate. The SECARMY the land and naval forces ... for calling forth the militia to reports to the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) and serves as execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections and civilian oversight for the U.S. Army and Chief of Staff of repel invasions.” the Army. The Chief of Staff of the Army (CSA) is an administrative position at the Pentagon held by a four-star Constitutional Provision general in the U.S. Army and is a statutory office (10 Article I, Section 8, Clause 12, known as the Army Clause. U.S.C. §3033). The CSA is the chief military advisor and “The Congress shall have Power To ... raise and support deputy to the SECARMY and serves as a member of the Armies ... ” Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), also a statutory office (10 Relevant Statutes U.S.C. §151). The JCS is composed of the DOD’s senior Title 10, U.S. Code, Subtitle B, Armed Forces: Army uniformed leaders who advise the President, SECDEF, and Cabinet officials as needed on military issues. Title 32, U.S. Code, National Guard Operational and Institutional Missions The Department of the Army (DA) is one of the three The operational Army—known as the Operational Force— military departments reporting to the Department of conducts or directly supports the full spectrum of military Defense (DOD).