State of NYC Dance & Workforce Demographics 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Panel Pool 2

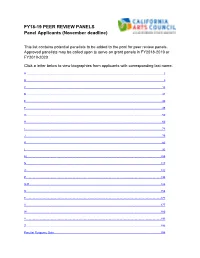

FY18-19 PEER REVIEW PANELS Panel Applicants (November deadline) This list contains potential panelists to be added to the pool for peer review panels. Approved panelists may be called upon to serve on grant panels in FY2018-2019 or FY2019-2020. Click a letter below to view biographies from applicants with corresponding last name. A .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 B ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 C ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18 D ............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 E ............................................................................................................................................................................. 40 F ............................................................................................................................................................................. 45 G ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Film Society of Lincoln Center and Dance Films Association announce the 41st edition of DANCE ON CAMERA February 1-5, 2013 Opening Night launches with the World Premiere of Alan Brown’s FIVE DANCES th Lineup highlights include the 50 Anniversary of Francisco Rovira Beleta’s flamenco classic, LOS TARANTOS; ice dancing with Olympic legend Dick Button, and a salute to pioneer dance filmmaker Shirley Clarke "A Dance of Light: Forty-Years of Self-Portraits by Arno Rafael Minkkinen," photography exhibit will be on display New York, NY, December 5, 2012 – The Film Society of Lincoln Center and Dance Films Association today announced the lineup for the 41st edition of Dance on Camera. Taking place February 1-5, the dance-centric film festival returns to the Film Society for the 17th consecutive year with an exciting and diverse array of dance films, including several premieres. This year’s selections range widely in subject and genre beginning with the Opening Night presentation of Alan Brown’s youthful, sexy contemporary coming of age film, FIVE DANCES, with stunning choreography by Jonah Bokaer. Closing Night honors will be shared by Sylvie Collier’s charming documentary TO DANCE LIKE A MAN, featuring the first known Cuban identical boy triplets - 11-year-old students at the National Ballet School in Havana, and Andrew Garrison’s TRASH DANCE inventive choreographed “dance” of Austin, Texas garbage collectors. "Dance on Camera is an exuberant hybrid. Its roots hold the seeds of innovation inherent in the concept of combining dance with cinematography in ways that alter one’s perception of both mediums," said Joanna Ney, co-curator of the Dance on Camera Festival. -

![Celia Ipiotis and Jeff Bush Eye on the Arts Archive [Finding Aid]. Music](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3617/celia-ipiotis-and-jeff-bush-eye-on-the-arts-archive-finding-aid-music-2873617.webp)

Celia Ipiotis and Jeff Bush Eye on the Arts Archive [Finding Aid]. Music

Celia Ipiotis and Jeff Bush Eye on the Arts Archive Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2013572127 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu018016 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2018 Collection Summary Title: Celia Ipiotis and Jeff Bush Eye on the Arts Archive Span Dates: 1994-2009 Call No.: ML31.I65 Creator: Ipiotis, Celia; Bush, Jeffrey C. Extent: 12,546 items Extent: 54 containers Extent: 28 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2013572127 Summary: The collection consists of programs, clippings, and press materials that cover New York City performances of music, dance, theater, as well as film and video. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Bush, Jeffrey C. Bush, Jeffrey C. Bush, Jeffrey C. Celia Ipiotis and Jeff Bush Eye on the Arts archive. 1994-2009. Ipiotis, Celia. Ipiotis, Celia. Organizations Arts Resources in Collaboration, Inc. Subjects Ballet. Dance companies--United States. Dance in motion pictures, television, etc.--United States. Dance--United States--History. Dance--United States. -

DCLA Cultural Organizations

DCLA Cultural Organizations Organization Name Address City 122 Community Center Inc. 150 First Avenue New York 13 Playwrights, Inc. 195 Willoughby Avenue, #402 Brooklyn 1687, Inc. PO Box 1000 New York 18 Mai Committee 832 Franklin Avenue, PMB337 Brooklyn 20/20 Vision for Schools 8225 5th Avenue #323 Brooklyn 24 Hour Company 151 Bank Street New York 3 Graces Theater Co., Inc. P.O. Box 442 New York 3 Legged Dog 33 Flatbush Avenue Brooklyn 42nd Street Workshop, Inc. 421 Eighth Avenue New York 4heads, Inc. 1022 Pacific St. Brooklyn 52nd Street Project, Inc. 789 Tenth Avenue New York 7 Loaves, Inc. 239 East 5th Street, #1D New York 826NYC, Inc. 372 Fifth Avenue Brooklyn A Better Jamaica, Inc. 114-73 178th Street Jamaica A Blade of Grass Fund 81 Prospect Street Brooklyn Page 1 of 616 09/28/2021 DCLA Cultural Organizations State Postcode Main Phone # Discipline Council District NY 10009 (917) 864-5050 Manhattan Council District #2 NY 11205 (917) 886-6545 Theater Brooklyn Council District #39 NY 10014 (212) 252-3499 Multi-Discipline, Performing Manhattan Council District #3 NY 11225 (718) 270-6935 Multi-Discipline, Performing Brooklyn Council District #33 NY 11209 (347) 921-4426 Visual Arts Brooklyn Council District #43 NY 10014 (646) 909-1321 Theater Manhattan Council District #3 NY 10163 (917) 385-0332 Theater Manhattan Council District #9 NY 11217 (917) 292-4655 Multi-Discipline, Performing Manhattan Council District #1 NY 10116 (212) 695-4173 Theater Manhattan Council District #3 NY 11238 (412) 956-3330 Visual Arts Brooklyn Council District -

Fiscal 2009 Cultural Development Fund Awardees

Fiscal 2009 Cultural Development Fund Awardees FY09 Total Organization Award 18 Mai Committee $7,200 3 Graces Theater Company $4,800 3 Legged Dog $24,000 52nd Street Project, Inc. $53,000 7 Loaves, Inc. $15,020 A Gathering of the Tribes $7,800 Aaron Davis Hall, Inc. $123,500 ABC No Rio $4,800 Abingdon Theatre Company $19,400 Academy of American Poets $14,400 Actors' Fund of America $14,400 African Film Festival, Inc. $24,000 African Voices Communications, Inc. $21,800 Afrikan Poetry Theatre, Inc. $65,357 Afro Brazil Arts $7,200 AHL Foundation, Inc. $12,000 AKTINA Productions, Inc. $14,400 All Out Arts, Inc. $19,100 Alley Pond Environmental Center, Inc. $116,800 Alliance for Downtown New York, Inc $96,000 Alliance for the Arts, Inc. $216,000 Alliance of Queens Artists, Inc. $4,800 Alliance of Resident Theatres / New York, Inc. $178,000 Allied Productions, Inc. $4,800 Alpha Omega 1-7 Theatrical Dance Company, Inc. $9,600 Alpha Workshops, Inc. $37,100 Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. $152,000 Alwan Foundation $12,000 Amas Musical Theatre, Inc. $33,600 American Composers Orchestra $48,000 American Documentary $24,000 American Folk Art Museum $216,000 American Friends of the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba $7,200 American Globe Theatre, Ltd. $9,600 American Indian Artists, Inc. $9,600 American Indian Community House, Inc. $14,400 American Lyric Theater Center, Inc. $12,000 American Music Center, Inc. $76,800 American Opera Projects, Inc. $14,400 American Place Theatre, Inc. $14,400 American Symphony Orchestra, Inc. $33,600 American Tap Dance Foundation, Inc. -

CIG Brooklyn Academy of Music David H. Koch Theater

CIG Brooklyn Academy of Music David H. Koch Theater Flushing Town Hall Jamaica Center for Arts & Learning Lincoln Center Metropolitan Museum El Museo del Barrio New York City Center Queens Theatre in the Park Snug Harbor Cultural Center Organizations that received New York City Cultural Affairs Department funding for dance projects in the 2016 Fiscal Year 7 Loaves, Inc. Arthur Aviles Typical Theatre, Inc. Aaron Davis Hall, Inc. Artichoke Dance Company, Inc. Alpha Omega 1-7 Theatrical Dance Company, Arts Connection, Inc. Inc. ARTs East New York Inc. Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. Arts For All, Inc. American Tap Dance Foundation, Inc. Art's House Schools, Inc. An Claidheamh Soluis, Inc. ASDT, Inc. - The American Spanish Dance Annabella Gonzalez Dance Theater, Inc. Theatre Apollo Theater Foundation, Inc. Ayazamana Cultural Center Art Sweats, Inc. Ballet Hispanico of New York, Inc. Ballet Next, Inc. Chez Bushwick, Inc. Ballet Tech Foundation, Inc. Circuit Productions, Inc. Ballet Theatre Foundation, Inc. City Parks Foundation Bang Group, Inc. Clemente Soto Velez Cultural and Educational Center, Inc. Baryshnikov Dance Foundation, Inc. College Community Services, Inc. Batoto Yetu, Inc. Conscientious Musical Revues Battery Dance Corporation Cora Incorporated Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation Covenant Ballet Theatre of Brooklyn, Inc. Big Tree Productions, Inc. Creative Capital Foundation Boys & Girls Harbor, Inc. Dance Continuum, Inc. BRIC Arts Media Bklyn Dance Entropy, Inc. Brighton Ballet Theater Company, Inc. Dance Parade, Inc. Bronx Dance Theatre, Inc. Dance Ring, Inc. Bronx House, Inc. Dance Service New York City, Inc. Brooklyn Arts Council, Inc. Dance Theatre Etcetera, Inc. Brooklyn Arts Exchange Dance Theatre of Harlem, Inc. -

Thesis Proposal

THE NEA AND THE DANCE FIELD: AN ANALYSIS OF GRANT RECIPIENTS FROM 1991 TO 2000 THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Ann Sciantarelli ***** The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Approved by Professor Margaret Wyszomirski, Advisor Professor Candace Feck ___________________________________ Advisor Arts Policy and Administration Program Copyright by Jennifer Ann Sciantarelli 2009 ABSTRACT The National Endowment for the Arts has been instrumental in the development of the dance field in the U.S. In the mid-1990s, the Agency transformed. Its budget was cut by 40 percent and the grant distribution process was restructured. The effects of restructuring on the dance field are examined in this study. NEA grants to the field from 1991 to 2000 were compiled into a database and explored through three distribution lenses: geography, genre and grantee type. When the NEA was restructured, artists prophesied disaster. In fact, data reveals that the field adapted to changes in federal subsidy and grew decentralized, diversified and connected to communities. After restructuring, while the dance field received less funding from the NEA, it maintained a consistent proportion of NEA grant dollars in comparison with other arts fields. This shows that the field can overcome obstacles, remaining competitive and vital to the American cultural landscape. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my advisor, Margaret Wyszomirski, for her guidance during my years in the Arts Policy and Administration program at Ohio State, as well as her patience during my thesis process. Dr. Wyszomirski also provided an invaluable collection of literature, including her set of NEA annual reports. -

State of Nyc Dance & Corporate Giving Acknowledgments

STATE OF NYC DANCE & CORPORATE GIVING ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Prepared by Cultural Data Project, Christopher Caltagirone, Senior Associate, Research Design: James H. Monroe, www.monroeand.co Elissa D. Hecker, Chair Photography: Jordan Matter Lane Harwell, Executive Director Dance/NYC’s mission is to promote and encourage the DanceNYC.org @DanceNYC knowledge, appreciation, practice, and performance of 218 East 18th Street, 4th floor dance in the metropolitan New York City area. It embeds New York, NY 10003 core values of equity and inclusion into all aspects of the (212) 966-4452 organization. Dance/NYC works in alliance with Dance/USA, The program is made possible by the New York State the national service organization for professional dance. Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew Board of Directors Elissa D. Hecker, Chair; Christopher Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Pennington, Vice Chair; Jina Paik, Treasurer; Juny E. Dance/NYC’s research is supported, in part, by the City of Francois; Gina Gibney; Eric Lilja; Susan Gluck Pappajohn; New York, Bill De Blasio, Mayor, and the New York City Council, Linda Shelton; Kristine A. Sova; Lane Harwell Melissa Mark-Viverito, Speaker, through the Department of Finance Committee Daniel Doucette; Alireza Esmaeilzadeh; Cultural Affairs, Tom Finkelpearl, Commissioner. Marianne Yip Love The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Lambent General Counsel Cory Greenberg Foundation Fund of Tides Foundation also provide institutional support for Dance/NYC research. Advisors Jody Gottfried Arnhold; -

For Immediate Release

Box 90772 Durham, NC 27708 phone: 919.684.6402 fax: 919.684.5459 North Carolina Press Contact: Sarah Tondu [email protected] 919.613.2188 National Press Contact: Lisa Labrado [email protected] 646.214.5812 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2016 SAMUEL H. SCRIPPS/AMERICAN DANCE FESTIVAL AWARD PRESENTED TO LAR LUBOVITCH Durham, NC, January 19, 2016-The American Dance Festival (ADF) will present the 2016 Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award for lifetime achievement to Artistic Director and choreographer, Lar Lubovitch. Established in 1981 by Samuel H. Scripps, the annual award honors choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of modern dance. Mr. Lubovitch's work, acclaimed throughout the world, is renowned for its musicality, emotional style, highly technical choreography, and deeply humanistic voice. The award will be presented to Mr. Lubovitch in a brief ceremony on Monday, July 11th at 7:00pm, prior to Lar Lubovitch Dance Company's performance at the Durham Performing Arts Center. "We are exceptionally delighted to honor Lar Lubovitch with this award. For decades, his breathtaking work has drawn audiences with its big, full-bodied, fluid movement, and year after year, he continues to draw the best dancers in the industry to perform his gorgeous works," stated ADF Director Jodee Nimerichter. Born in Chicago in 1943, Lar Lubovitch began his dance education at The Juilliard School in NYC in 1962, where his teachers were Martha Graham, José Limón, Anthony Tudor, and Donald McKayle, in whose company Mr. Lubovitch subsequently began his professional career. In 1968, after performing in numerous modern, ballet, and jazz companies, he created the Lar Lubovitch Dance Company, now in its 48th season. -

A. Donlin Foreman January 12, 2010 Associate Professor of Professional

Last modified 2/3/10 A. Donlin Foreman January 12, 2010 Associate Professor of Professional Practice Dance Department 3647 Broadway Apt 9C Barnard College/Columbia University New York, NY 10031 3009 Broadway Tel (646) 265-8189 New York, NY 10027-6598 On Common Ground Co-Founder/Artistic Director & Choreographer 2006 - Present Dance educational and performance projects www.danceocg.org Buglisi/Foreman Dance /Threshold Dance Projects, Inc Founding Co-Artistic Director/Choreographer Emeritus 1991 - 05 B. Higher Education Enrolled at these universities while developing a professional career in dance. University of Montevallo, Montevallo, Alabama 1970-73 Theater Major under Dr. Charles Harbor. Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida Summer 1973 Dance Major under Dr. Nancy Smith The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah Spring 1974 Dance Major under Willam Christiansen C. Professional Training: Modern Dance: Jeanette Crew, Professor, University of Montevallo 1971-72 My first dance training was in the Physical Education Department at the University of Montevallo where I studied two levels of modern dance and one level of social dance under Ms Jeanette Crew and also performed my first dance performances in the dance club Orchesis she directed. [I credit her with my recognition that becoming a dancer was something I could actually do in my life] Martha Graham Dance Company; New York, New York 1977-97 Martha Graham, Artistic Director/Choreographer 1977-91 Coached and directed in every major male role of her repertory. Linda Hodes, Associate Artistic Director 1977-92 Coached and directed in Graham technique as well as general repertory. Pearl Lang, Artistic Associate 1980-94 Coached and directed in the reconstruction of Deaths and Entrances, Appalachian Spring, Letter to the World.