Chapter 2: Challenges, Resources, and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

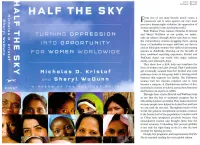

2016 Austin College Posey Leadership Award Co-Recipients: Sheryl Wudunn & Nicholas Kristof

2016 Austin College Posey Leadership Award Co-Recipients: Sheryl WuDunn & Nicholas Kristof Founders of the Half the Sky Movement Sheryl WuDunn grew up in New York City, a third-generation Chinese American hailing from the Upper West Side. She earned an MBA from Harvard Business School and a master’s degree in public administration from Princeton University. WuDunn has worked in investment management at Goldman, Sachs & Co. and was a commercial loan officer at Bankers Trust. In addition, she spent time at The New York Times as both a journalist and an executive. During her time as a journalist, WuDunn and her husband, Nicholas Kristof, won a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of China’s Tiananmen Square movement in 1990. Nicholas Kristof grew up on a sheep and cherry farm near Yamhill, Oregon. He graduated from Harvard College and won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, where he studied law. He later studied Arabic in Cairo and Chinese in Taipei. Kristof’s work has taken him all over the world. He has lived on four continents, reported on six, and traveled to more than 150 countries, plus all 50 U.S. states, every Chinese province, and every main Japanese island. Joining The New York Times in 1984, Kristof initially covered economics. Since 2001, he has maintained an op-ed column. In addition to his 1990 Pulitzer honors for coverage of China’s Tiananmen Square movement, Kristof won a second Pulitzer Prize in 2006 for his journalistic coverage of the genocides in Darfur. The latest book by WuDunn and Kristof is A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunity (2014). -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Applying a Framework to Assess Deterrence of Gray Zone Aggression for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N MICHAEL J. MAZARR, JOE CHERAVITCH, JEFFREY W. HORNUNG, STEPHANIE PEZARD What Deters and Why Applying a Framework to Assess Deterrence of Gray Zone Aggression For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3142 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0397-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: REUTERS/Kyodo Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled What Deters and Why: North Korea and Russia, sponsored by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7, U.S. -

Gay Rights: Our Future GABRIEL BOUYS / Ge Tt Y I M Ages

TURMOIL IN AFRICA • TORTURE IN IRAN Vital Signs 1 GABRIEL BOUYS / GETTY IMAGES Future Our Rights: Gay LETTER FROM THE EDITOR IN THIS Awareness and Passion ISSUE of violence and hopelessness. The unfathom- BY NEHA SRIVA S TAVA able warring between the Hutus and Tutsis of Rwanda resulted in pure genocide. Yet, who is “Triumph of A Dreamer,” a recent op-ed to argue that the next Curie or vos Savant could Awareness and Passion by Nicholas D. Kristof in The New York not have existed among the millions killed? NEHA SRIVA S TAVA . 2. Times, exquisitely captures the extent of So many people lack the means of obtaining Gay Rights: Our Future human potential evidenced by a passionate education that would permit them to rise up SEA N SALAMO N . 3. individual. In the article, he traces the life of and develop their talents. We cannot selfishly Too Broke to Teach? Tererai Trent, a woman who escaped rural assume that it is only we who possess talent CAROLI N E DREYFU ss . 4. Zimbabwean poverty to pursue a Doctorate and brains in this world. degree in America. With an abusive husband It’s crucial to see both sides of the coin: Learning from the World and five children yet still desiring an educa- for millions of people worldwide, progress KIRA N BHATT . 5. tion, Trent exemplifies those who have the takes a combination of individual persistence Obama on Wall Street talent and determination to and social help. These ar- AL B ERT MAG N ELL . 6. triumph despite all odds. -

Wholexthesis-23-1 5Th1.Pdf (745.4Kb)

UIO WHAT’S MY IMAGE IN YOUR REPORTS Rediscussing Objectivity in International News ‐‐The Case of the New York Times and the People’s Daily MASTER THESIS Department of Media and Communication University of Oslo, Norway TAOTAO LIU SPING 2009 SUMMARY This is a 15-day research study aimed at showing how two newspapers, the New York Times and the People’s Daily, report on issues relating to each other countries i.e. The United States and China respectively. It is conducted in the comparative and analysis manner with the aim of finding out whether the two newspapers reported each other’s countries objectively. The quantitative and qualitative methods demonstrate that the problems related to objectivity that are reflected in the two newspapers are also connected to quantity and quality. This is because while reporting about Chinese issues, the New York Times had a total percentage of 67 of all its news items having a negative attitude. While reporting on the issues of the United States, the People’s Daily had more news items with a “superficial” neutral attitude. As a result, in certain aspects, the two elite newspapers violate the principle of objectivity. The differences between the two newspapers, such as the ownership, their writing style, and economy, culture and foreign policy, are the factors that resulted in the problems of the two newspapers that were reflected in this study. Nevertheless, the international integration has evolved into an unstoppable tendency, expanding from the economic field, slowly into the political and cultural field among different countries around the world. Objective international coverage could be the bridge that could connect countries and promote mutual understanding between them. -

Delve Deeper Into Motherland a Film by Ramona Diaz

Delve Deeper into Motherland A film by Ramona Diaz This list of fiction and poverty, about the abuse they Cornog, Martha and Timothy nonfiction books, compiled have endured, about their Perper. For SEX EDUCATION, by Robert Surratt of the San eagerness for meaningful work, See Librarian: A Guide to Diego Public Library, and about their inventiveness in Issues and Resources. provides a range of stretching scarce dollars. In a Greenwood, 1996. At long perspectives on the issues policy debate increasingly last, here is the definitive raised by the POV dominated by shrill, punitive practical guide to sexuality documentary Motherland. voices, Schein argues that the materials in libraries and an experiences and collective annotated bibliography of nearly Motherland is an absorbingly wisdom of these women cannot 600 recommended books for intimate, vérité look at the be ignored. school and public libraries. busiest maternity hospital on Cornog and Perper, the the planet, in one of the world's Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer. Mother preeminent experts on sexuality most populous countries: the Nature: A History of Mothers, materials for libraries, provide Philippines. Women share their Infants, and Natural guidelines for materials stories with other mothers, their Selection. New York, NY: selection, reference, processing, families, doctors and social Pantheon Books, 1999. access, programming, and workers. In a hospital that is Maternal instinct—the all- dealing with problems of literally bursting with life, we consuming, utterly selfless love vandalism and censorship. The witness the miracle and wonder that mothers lavish on their bibliography, organized into 5 of the human condition. children—has long been topics and 48 subtopics, assumed to be an innate, annotates a collection of ADULT NONFICTION indeed defining element of a recommended books and woman's nature. -

The New York Times 2014 Innovation Report

Innovation March 24, 2014 Executive Summary Innovation March 24, 2014 2 Executive Summary Introduction and Flipboard often get more traffic from Times journalism than we do. The New York Times is winning at journalism. Of all In contrast, over the last year The Times has the challenges facing a media company in the digi- watched readership fall significantly. Not only is the tal age, producing great journalism is the hardest. audience on our website shrinking but our audience Our daily report is deep, broad, smart and engaging on our smartphone apps has dipped, an extremely — and we’ve got a huge lead over the competition. worrying sign on a growing platform. At the same time, we are falling behind in a sec- Our core mission remains producing the world’s ond critical area: the art and science of getting our best journalism. But with the endless upheaval journalism to readers. We have always cared about in technology, reader habits and the entire busi- the reach and impact of our work, but we haven’t ness model, The Times needs to pursue smart new done enough to crack that code in the digital era. strategies for growing our audience. The urgency is This is where our competitors are pushing ahead only growing because digital media is getting more of us. The Washington Post and The Wall Street crowded, better funded and far more innovative. Journal have announced aggressive moves in re- The first section of this report explores in detail cent months to remake themselves for this age. First the need for the newsroom to take the lead in get- Look Media and Vox Media are creating newsrooms ting more readers to spend more time reading more custom-built for digital. -

Kristofwudunnhalftheskychapte

CHAPTER TWELVE The Axis of Equality A woman has so many parts to her body, life is very hard indeed. -LU XUN, "ANXIOUS THOUGHTS ON 'NATURAL BREASTS' "(1927) l ]{ Te've been chronicling the world of impoverished women, but V V let's break for a billionaire. Zhang Yin is a petite, ebullient Chinese woman who started her career as a garment worker, earning $6 a month to help support her seven siblings. Then, in the early 1980s, she moved to the special eco Turning Oppression into Opportunity nomic zone of Shenzhen and found a job at a paper trading company partly owned by foreigners. Zhang Yin learned the intricacies of the for Women Worldwide paper business, and she could have stayed and risen in the firm. But she is a restless, ambitious woman, buzzing with entrepreneurial energy, so she struck out for Hong Kong in 1985 to work for a trading company there. The company went bankrupt within a year. Zhang Yin then started her own company in Hong Kong, buying scrap paper there and NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF shipping it to firms throughout China. She soon realized that the grand AND SHERYL WUDUNN arbitrage opportunity was between waste paper in the United States and in China. Since China has few forests, much of its paper is made from straw or bamboo and is of execrable quality. That made recy clable American scrap paper, derived from wood pulp and worth very little locally, a valuable commodity in China-particularly as industri alization led to soaring demaqd for paper. Working with her husband, a Taiwanese, Zhang Yin at first bought American scrap paper through intermediaries, but in 1990 she moved to Los Angeles and began to work out of her home. -

From Two of Our Most Fiercely Moral Voices, A

U.S.A. :)>27·95 CANADA $34.00 rom two of our most fiercely moral voices, a Fpassionate call to arms against our era's most pervasive human rights violation: the oppression of women and girls in the developing world. With Pulitzer Prize winners Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn as our guides, we under take an odyssey through Africa and Asia to meet the extraordinary women struggling there, among them a Cambodian teenager sold into sex slavery and an Ethiopian woman who suffered devastating injuries in childbirth. Drawing on the breadth of their combined reporting experience, Kristof and WuDunn depict our world with anger, sadness, clarity, and, ultimately, hope. They show how a little help can transform the lives of women and girls abroad. That Cambodian girl eventually escaped from her brothel and, with assistance from an aid group, built a thriving retail business that supports her family. The Ethiopian woman had her injuries repaired and in time became a surgeon. A Zimbabwean mother of five, counseled to return to school, earned her doctorate and became an expert on AIDS. Through these stories, Kristof and WuDunn help us see that the key to economic progress lies in unleashing women's potential. They make clear how so many people have helped to do just that, and how we can each do our part. Throughout much of the world, the greatest unexploited economic resource is the fema le half of the population. Countries such as China have prospered precisely hecause they emancipated women and brought them into the form al economy. -

OPC Forges Partnership to Promote Journalists' Safety Club Mixers To

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • November 2014 OPC Forges Partnership to Promote Journalists’ Safety By Marcus Mabry compact between Your OPC has been busy! Since news organiza- the new officers and board of gov- tions and journal- ernors took office at the end of ists, in particular the summer, we have dedicated freelance, around ourselves to three priorities, all safety and profes- designed to increase the already sionalism. We have impressive contribution that the only just begun, but OPC makes to our members and our partners include our industry. the Committee to We have restructured the board Protect Journalists, to dedicate ourselves to services Reporters Without for members, both existing and po- Borders, the Front- tential, whether those members are line Club, the In- Clockwise from front left: Vaughan Smith, Millicent veteran reporters and editors, free- ternational Press Teasdale, Patricia Kranz, Jika Gonzalez, Michael Luongo, Institute’s Foreign Sawyer Alberi, Judi Alberi, Micah Garen, Marcus Mabry, lancers or students. In addition to Charles Sennott, Emma Daly and Judith Matloff dining services, we have reinvigorated our Editors Circle and after a panel of how to freelance safety. See page 3. social mission, creating a committee the OPC Founda- dedicated to planning regular net- tion. We met in September at The you need and the social events you working opportunities for all mem- New York Times headquarters to want. And, just as important, get bers. So if you are in New York – or try to align efforts that many of our friends and colleagues who are not coming through New York – look us groups had started separately. -

Spotlight 2013 Spring Newsletter Tumes and Talented Youngsters from Local Language Schools

OCA-WHV | EMBRACING THE HOPES AND ASPIRATIONS OF ASIAN PACIFIC AMERCIANS Spotlight 2013 Spring Newsletter tumes and talented youngsters from local language schools. The festival is also a showcase for local small busi- nesses and non-profits, featuring vendors selling Asian-themed cultural artifacts and handmade goods, agencies offering educational and health services and restaurants cooking up a wide array of Asian foods, South Indian to Cantonese, for the hungry public. This festival attracts as many as 7,000 resi- dents to the Dam each year. Admission is free. The Rising Stars Concert This event showcases the considerable musical tal- ents of local young Asian Americans to the communi- ty-at-large. Musicians from the ages of 7 to 18 com- Who We Are and What We Do pete for a place on the program via audition by a pan- el of professional musicians and teachers. Those The Westchester-Hudson Valley chapter of OCA is one of the selected perform a variety of musical selections, leading social advocacy and cultural organizations in the western classical to traditional Asian, on instruments county. Our talented and committed membership sponsors a ranging from piano to the yangqin. This year, two full calendar of events and projects, all of which celebrate the concerts were held, one at Steinway Hall and another growing presence of Asian Americans in the Hudson Valley at the Chappaqua Library Auditorium. area and raise awareness of our needs and concerns. A de- scription of our mission and an outline of our most important The Dynamic Achiever Awards Gala activities follow below. -

Sex Trafficking and Intergenerational Prostitution

DISCUSSION GUIDE SEX TRAFFICKING AND INTERGENERATIONAL PROstITUTION PBS.ORG/independenTLens/HALF-THE-SKY Table of Contents 1 Using This Guide 2–3 From the Filmmaker 4–6 The Film 5 The Film: Episode One 6 The Film: Episode Two 7–8 Background Information 7–8 AFESIP Cambodia: Somaly Mam and Sex Trafficking in Cambodia 9 New Light: Urmi Basu and Intergenerational Prostitution 10 Apne Aap: Ruchira Gupta and Prostitution and Sexual Slavery in India 11 Root Causes and Contributing Factors 11 Contemporary Slavery: The Global Slave Trade 12 Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking of Women and Girls 13 What is Needed? 14–15 Thinking More Deeply 16 Suggestions for Action 17–18 Resources PHOTO CREDITS: JOSH BENNETT, JESSICA CHERMAYEFF, NICK KRISTOF, JENNI MORELLO, DAVID SMOLER Using This Guide Community Cinema is a rare public forum: a space for people to gather who are connected by a love of stories, and a belief in their power to change the world. This discussion guide is designed as a tool to facilitate dialogue, and deepen understanding of the complex issues in Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide. It is also an invitation to not only sit back and enjoy the show – but to step up and take action. This guide is not meant to be a comprehensive primer on a given topic. Rather, it provides important context, and raises thought provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply. We provide suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also provide valuable resources, and connec- tions to organizations on the ground that are fighting to make a difference.