Contrail Microphysics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Modeling of Contrail and Contrail Cirrus Climate Impact

GLOBAL MODELING OF THE CONTRAIL AND CONTRAIL CIRRUS CLIMATE IMPACT BY ULRIKE BU RKHARDT , BERND KÄRCHER , AND ULRICH SCH U MANN et al. 2010). For the given ambient Modeling the physical processes governing the life cycle of conditions, their direct radia- contrail cirrus clouds will substantially narrow the uncer- tive effect is mainly determined tainty associated with the aviation climate impact. by coverage and optical depth. The microphysical properties of contrail cirrus likely differ from substantial part of the aviation climate impact those of most natural cirrus, at least during the initial may be due to aviation-induced cloudiness (AIC; stages of the contrail cirrus life cycle (Heymsfield A Brasseur and Gupta 2010), which is arguably et al. 2010). Contrails form and persist in air that is the most important but least understood component ice saturated, whereas natural cirrus usually requires in aviation climate impact assessments. The AIC in- high ice supersaturation to form (Jensen et al. 2001). cludes contrail cirrus and changes in cirrus properties This difference implies that in a substantial fraction or occurrence arising from aircraft soot emissions of the upper troposphere contrail cirrus can persist in (soot cirrus). Linear contrails are line-shaped ice supersaturated air that is cloud free, thus increasing clouds that form behind cruising aircraft in clear air high cloud coverage. Contrails and contrail cirrus and within cirrus clouds. Linear contrails transform existing above, below, or within clouds change the into irregularly shaped ice clouds (contrail cirrus) and column optical depth and radiative fluxes. They may may form cloud clusters in favorable meteorological also indirectly affect radiation by changing the mois- conditions, occasionally covering large horizontal ture budget of the upper troposphere, and therefore areas extending up to 100,000 km2 (Duda et al. -

WMO, No. 407 International Cloud Atlas, Volume II

·..- INTERNATIONAL CLOUD ATLAS Volume 11 WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION 11"]~ii[Ulilliiill~lllifiiilllll INTERNATIONAL CLOUD ATLAS Volume 11 11'-;> oz-; WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION 1987 © 1987, World Meteorological Organization ISBN 92 - 63 - L2407 - 8 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The photographs contained in this volume may not be reproduced without the authoriza tion of the copyright owner. All inquiries regarding reproduction rights should be addressed to the Secretary-General, World Meteorological Organization, Geneva (Switzerland). 03- 4365 v'Z, c ~~ FOREWORD With this new, thoroughly revised edition of Volume 11 of the Study of Clouds. A modified edition of the same work appeared in International Cloud Atlas a key publication is once again made 1939, under the title International Atlas 0/ Clouds and of Types 0./ available for professional meteorologists as well as for a wide circle of Skies, Volume I, General Atlas. The latter contained 174 plates: IQ I interested amateurs. For meteorologists this is a fundamental hand cloud photographs taken from the ground and 22 from aeroplanes, and book, for others a source of acquaintance with the spectacular world of 51 photographs of types of sky. From those photographs, 31 were clouds. printed in two colours (grey and blue) to distinguish between the blue The present internationally adopted system of cloud classification of the sky and the shadows of the clouds. -

Observation of Polar Stratospheric Clouds Down to the Mediterranean Coast

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 5275–5281, 2007 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/7/5275/2007/ Atmospheric © Author(s) 2007. This work is licensed Chemistry under a Creative Commons License. and Physics Observation of Polar Stratospheric Clouds down to the Mediterranean coast P. Keckhut1, Ch. David1, M. Marchand1, S. Bekki1, J. Jumelet1, A. Hauchecorne1, and M. Hopfner¨ 2 1Service d’Aeronomie,´ Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, B.P. 3, 91371, Verrieres-le-Buisson,` France 2Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, Institut fur¨ Meteorologie und Klimaforschung, Karlsruhe, Germany Received: 8 March 2007 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 15 May 2007 Revised: 5 October 2007 – Accepted: 6 October 2007 – Published: 12 October 2007 Abstract. A Polar Stratospheric Cloud (PSC) was detected spheric temperatures are expected to cool down due to ozone for the first time in January 2006 over Southern Europe af- depletion, but also to the increase in the concentrations of ter 25 years of systematic lidar observations. This cloud greenhouse gases. Such findings are already reported and was observed while the polar vortex was highly distorted simulated (Ramaswamy et al., 2001), although trends are less during the initial phase of a major stratospheric warming. clear at high latitudes due to a larger natural variability and Very cold stratospheric temperatures (<190 K) centred over potential dynamical feedback. Nearly twenty years after the the Northern-Western Europe were reported, extending down signing of the Montreal Protocol, the timing and extent of the to the South of France -

Cloud Atlas? 5

Episode 9 Teacher Resource 4th April 2017 Clouds 1. Briefly explain how clouds form. Students will develop an 2. Why are clouds an important part of the earth’s atmosphere? understanding of how clouds form and the different types of clouds. 3. What does a meteorologist study? 4. What is a Cloud Atlas? 5. When was it first published? 6. What does a cumulus cloud look like? 7. What is the name of the cloud that brings rain and lightning? 8. The Cloud Atlas has special clouds that are defined by the unusual Science – Year 4 ways they form. Give an example of one. Represent and communicate observations, ideas and findings 9. Describe the cloud that Gary helped get into the Cloud Atlas. using formal and informal 10. What do you understand more clearly since watching the BTN representations (ACSIS071) story? Science – Year 5 Solids, liquids and gases have different observable properties a nd behave in different ways (ACSSU077) Science – Year 7 Class Discussion Some of Earth’s resources are Watch the BTN Cloud Atlas story and discuss the information raised as a renewable, including water that cycles through the environment, class. What questions do students have (what are the gaps in their but others are non-renewable knowledge)? The following questions may help guide the discussion: (ACSSU116) What are clouds? Come up with a definition. What have you noticed about clouds? How do clouds form? What are the main types of clouds? What is the Cloud Atlas? The following KWLH organiser provides students with a framework to explore their knowledge on this topic and consider what they would like to know and learn. -

Aerosols, Their Direct and Indirect Effects

5 Aerosols, their Direct and Indirect Effects Co-ordinating Lead Author J.E. Penner Lead Authors M. Andreae, H. Annegarn, L. Barrie, J. Feichter, D. Hegg, A. Jayaraman, R. Leaitch, D. Murphy, J. Nganga, G. Pitari Contributing Authors A. Ackerman, P. Adams, P. Austin, R. Boers, O. Boucher, M. Chin, C. Chuang, B. Collins, W. Cooke, P. DeMott, Y. Feng, H. Fischer, I. Fung, S. Ghan, P. Ginoux, S.-L. Gong, A. Guenther, M. Herzog, A. Higurashi, Y. Kaufman, A. Kettle, J. Kiehl, D. Koch, G. Lammel, C. Land, U. Lohmann, S. Madronich, E. Mancini, M. Mishchenko, T. Nakajima, P. Quinn, P. Rasch, D.L. Roberts, D. Savoie, S. Schwartz, J. Seinfeld, B. Soden, D. Tanré, K. Taylor, I. Tegen, X. Tie, G. Vali, R. Van Dingenen, M. van Weele, Y. Zhang Review Editors B. Nyenzi, J. Prospero Contents Executive Summary 291 5.4.1 Summary of Current Model Capabilities 313 5.4.1.1 Comparison of large-scale sulphate 5.1 Introduction 293 models (COSAM) 313 5.1.1 Advances since the Second Assessment 5.4.1.2 The IPCC model comparison Report 293 workshop: sulphate, organic carbon, 5.1.2 Aerosol Properties Relevant to Radiative black carbon, dust, and sea salt 314 Forcing 293 5.4.1.3 Comparison of modelled and observed aerosol concentrations 314 5.2 Sources and Production Mechanisms of 5.4.1.4 Comparison of modelled and satellite- Atmospheric Aerosols 295 derived aerosol optical depth 318 5.2.1 Introduction 295 5.4.2 Overall Uncertainty in Direct Forcing 5.2.2 Primary and Secondary Sources of Aerosols 296 Estimates 322 5.2.2.1 Soil dust 296 5.4.3 Modelling the Indirect -

Persistent Contrails and Contrail Cirrus. Part I: Large-Eddy Simulations from Inception to Demise

DECEMBER 2014 L E W E L L E N E T A L . 4399 Persistent Contrails and Contrail Cirrus. Part I: Large-Eddy Simulations from Inception to Demise D. C. LEWELLEN,O.MEZA,* AND W. W. HUEBSCH West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia (Manuscript received 2 October 2013, in final form 10 March 2014) ABSTRACT Large-eddy simulations with size-resolved microphysics are used to model persistent aircraft contrails and contrail-induced cirrus from a few wing spans behind the aircraft until their demise after many hours. Schemes for dynamic local ice binning and updating coupled radiation dynamically as needed in individual columns were developed for numerical efficiency, along with a scheme for maintaining realistic ambient turbulence over long times. These capabilities are used to study some of the critical dynamics involved in contrail evo- lution and to explore the simulation features required for adequate treatment of different components. A ‘‘quasi 3D’’ approach is identified as a useful approximation of the full dynamics, reducing the computation to allow a larger parameter space to be studied. Ice crystal number loss involving competition between different crystal sizes is found to be significant for both young contrails and aging contrail cirrus. As a consequence, the sensitivity to the initial number of ice crystals in the contrail above a threshold is found to decrease signifi- cantly over time, and uncertainties in the ice deposition coefficient and Kelvin effect for ice crystals assume an increased importance. Atmospheric turbulence is found to strongly influence contrail properties and lifetime in some regimes. Water from fuel consumption is found to significantly reduce aircraft-wake-induced ice crystal loss in colder contrails. -

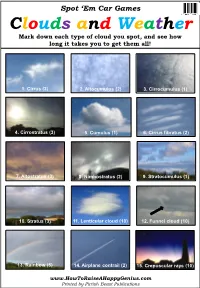

Cloud-Spotting Game Sheet

Spot ‘Em Car Games Clouds and Weather Mark down each type of cloud you spot, and see how long it takes you to get them all! 1. Cirrus (2) 2. Altocumulus (2) 3. Cirrocumulus (1) 4. Cirrostratus (3) 5. Cumulus (1) 6. Cirrus fibratus (2) 7. Altostratus (3) 8. Nimbostratus (2) 9. Stratocumulus (1) 10. Stratus (3) 11. Lenticular cloud (10) 12. Funnel cloud (10) 13. Rainbow (5) 14. Airplane contrail (2) 15. Crepuscular rays (10) www.HowToRaiseAHappyGenius.com Printed by Pictish Beast Publications Spot ‘Em Car Games Clouds and Weather More information about how to identify the weather phenomena that are part of this car game 1. Cirrus: Cirrus clouds look like strands of white cotton wool that have been pulled apart and spread across the sky. 2. Altocumulus: Altocumulus clouds form a layer at mid-altitudes that covers much of the sky, and this layer is usually made up of patterns of regularly spaced and shaped patches with bands of blue sky between them. 3. Cirrocumulus: Cirrocumulus clouds are similar to altocumulus, but they are found higher up in the sky and are made up of smaller patches of cloud. 4. Cirrostratus: Cirrostratus clouds form a continuous sheet of cloud high up in the sky that are thin enough for the sun to be able to shine through, creating a halo effect. 5. Cumulus: Cumulus clouds are distinctive fluffy looking clouds that are clearly separated from other clouds in the sky. They are what you would draw if asked to draw a picture of a cloud. 6. Cirrus fibratus: Cirrus fibratus are a type of Cirrus cloud that form very distinctive long, fluffy lines across the sky. -

On the Possibility of Weather Modification by Aircraft Contrails

October 1970 745 UDC 651.&€19.6’3:551.576.1:629.135.2(798) ON THE POSSIBILITY OF WEATHER MODIFICATION BY AIRCRAFT CONTRAILS WALLACE B. MURCRAY Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, College, Alaska ABSTRACT The possible effect of contrails in modifying the weather is reconsidered in the light of information obtained from ground-level contrails in Alaska. It appears likely that inadvertent cloud seeding by jet aircraft may be of the same order of magnitude as that attained in commercial cloud seeding operations. Further investigation is needed; but in the meantime, the possibility of contrail contamination should be kept in mind when evaluating the results of seeding operations. 1. INTRODUCTION frequently such that a contrail is left while the aircraft is taxiing and taking off or landing so that it is easily Aircraft contrails first attracted public attention during accessible for study. (On the ground, the contrail is called World War 11; but as air traffic has built up to its present ice fog, and it can become a serious problem in flight of the environ- level, they have come to be accepted as part operations.) This discussion is based on observations made ment. Even during World War 11, it kas difficult to watch under the direction of Ohtako (1967; see also Huffman the cloud cover laid down by a large bomber formation 1968) during the course of investigations of ice fog from without wondering what it might be doing to the weather; this and other sources. As a result of these observations, at present, there is widespread belief among the general enough is known about the way the contrail is formed to public and some feeling among scientists (Fletcher 1969, make it safe to state that the contrail formed at cruising Reinking 1968, Livingston 1969, and Schaefer 1969) that altitude is very unlikely to differ greatly from that formed contrails are increasing cloudiness, if nothing more, in on the ground. -

Ice Polar Stratospheric Clouds Detected from Assimilation of Atmospheric Infrared Sounder Data

Ice Polar Stratospheric Clouds Detected from Assimilation of Atmospheric Infrared Sounder Data Ivanka Stajner,1,2 Craig Benson,3,2 Hui-Chun Liu,1,2 Steven Pawson,2 Nicole Brubaker,1,2 Lang-Ping Chang,1,2 Lars Peter Riishojgaard3,2, and Ricardo Todling1,2 1 Science Applications International Corporation, Beltsville, Maryland 2 Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland 3 Goddard Earth Sciences and Technology Center, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, Maryland 1 A novel technique is presented for the detection and 45 about ice PSCs (Meerkoetter 1992; Hervig et al. 2001). 2 mapping of ice polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs), 46 Maps of ice PSCs were retrieved from differences in 3 using brightness temperatures from the Atmospheric 47 radiances in two channels and also allowed distinction 4 Infrared Sounder (AIRS) “moisture” channel near 48 between ice PSCs and cirrus. In contrast, even the 5 6.79 μm. It is based on observed-minus-forecast 49 strongest nitric-acid-trihydrate PSCs cannot be 6 residuals (O-Fs) computed when using AIRS 50 retrieved from AVHRR because their signal falls below 7 radiances in the Goddard Earth Observing System 51 AVHRR measurement uncertainty (Hervig et al. 2001). 8 version 5 (GEOS-5) data assimilation system. 52 Tropospheric ice clouds can be retrieved from the 9 Brightness temperatures are computed from six-hour 53 Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) data. 10 GEOS-5 forecasts using a radiation transfer module 54 Comparisons of AIRS spectra with a radiative transfer 11 under clear-sky conditions, meaning they will be too 55 model in the window region 10-12.5 μm show 12 high when ice PSCs are present. -

Contrails, Contrail Cirrus, and Ship Tracks

214 Proceedings of the TAC-Conference, June 26 to 29, 2006, Oxford, UK Contrails, contrail cirrus, and ship tracks K. Gierens* DLR-Institut für Physik der Atmosphäre Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany Keywords: Aerosol effects on clouds and climate ABSTRACT: The following text is an enlarged version of the conference tutorial lecture on con- trails, contrail cirrus, and ship tracks. I start with a general introduction into aerosol effects on clouds. Contrail formation and persistence, aviation’s share to cirrus trends and ship tracks are treated then. 1 INTRODUCTION The overarching theme above the notions “contrails”, “contrail cirrus”, and “ship tracks” is the ef- fects of anthropogenic aerosol on clouds and on climate via the cloud’s influence on the flow of ra- diation energy in the atmosphere. Aerosol effects are categorised in the following way: - Direct effect: Aerosol particles scatter and absorb solar and terrestrial radiation, that is, they in- terfere directly with the radiative energy flow through the atmosphere (e.g. Haywood and Boucher, 2000). - Semidirect effect: Soot particles are very effective absorbers of radiation. When they absorb ra- diation the ambient air is locally heated. When this happens close to or within clouds, the local heating leads to buoyancy forces, hence overturning motions are induced, altering cloud evolu- tion and potentially lifetimes (e.g. Hansen et al., 1997; Ackerman et al., 2000). - Indirect effects: The most important role of aerosol particles in the atmosphere is their role as condensation and ice nuclei, that is, their role in cloud formation. The addition of aerosol parti- cles to the natural aerosol background changes the formation conditions of clouds, which leads to changes in cloud occurrence frequencies, cloud properties (microphysical, structural, and op- tical), and cloud lifetimes (e.g. -

The Contrail Mitigation Potential of Aircraft Formation Flight Derived from High-Resolution Simulations

aerospace Article The Contrail Mitigation Potential of Aircraft Formation Flight Derived from High-Resolution Simulations Simon Unterstrasser Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt, Institut für Physik der Atmosphäre, Oberpfaffenhofen, 82234 Wessling, Germany; [email protected] Received: 3 November 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 5 December 2020 Abstract: Formation flight is one potential measure to increase the efficiency of aviation. Flying in the upwash region of an aircraft’s wake vortex field is aerodynamically advantageous. It saves fuel and concomitantly reduces the carbon foot print. However, CO2 emissions are only one contribution to the aviation climate impact among several others (contrails, emission of H2O and NOx). In this study, we employ an established large eddy simulation model with a fully coupled particle-based ice microphysics code and simulate the evolution of contrails that were produced behind formations of two aircraft. For a large set of atmospheric scenarios, these contrails are compared to contrails behind single aircraft. In general, contrails grow and spread by the uptake of atmospheric water vapour. When contrails are produced in close proximity (as in the formation scenario), they compete for the available water vapour and mutually inhibit their growth. The simulations demonstrate that the contrail ice mass and total extinction behind a two-aircraft formation are substantially smaller than for a corresponding case with two separate aircraft and contrails. Hence, this first study suggests that establishing formation flight may strongly reduce the contrail climate effect. Keywords: climate impact; aviation; formation flight; mitigation potential; large-eddy simulation LES; particle-based ice microphysics; wake vortex 1. Introduction Formation flight (FF) is a well-known strategy of migratory birds in order to improve their aerodynamic efficiency, save energy and increase their range [1–3]. -

20 WCM Words

Spring, 2017 - VOL. 22, NO. 2 Evan L. Heller, Editor/Publisher Steve DiRienzo, WCM/Contributor Ingrid Amberger, Webmistress FEATURES 2 Ten Neat Clouds By Evan L. Heller 10 Become a Weather-Ready Nation Ambassador! By Christina Speciale 12 Interested in CoCoRaHS? By Jennifer Vogt Miller DEPARTMENTS 14 Spring 2017 Spotter Training Sessions 16 ALBANY SEASONAL CLIMATE SUMMARY 18 Tom Wasula’s WEATHER WORD FIND 19 From the Editor’s Desk 20 WCM Words Northeastern StormBuster is a semiannual publication of the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Albany, New York, serving the weather spotter, emergency manager, cooperative observer, ham radio, scientific and academic communities, and weather enthusiasts, all of whom share a special interest or expertise in the fields of meteorology, hydrology and/or climatology. Non-Federal entities wishing to reproduce content contained herein must credit the National Weather Service Forecast Office at Albany and any applicable authorship as the source. 1 TEN NEAT CLOUDS Evan L. Heller Meteorologist, NWS Albany There exist a number of cloud types based on genera as classified in the International Cloud Atlas. Each of these can also be sub-classified into one of several possible species. These can further be broken down into one of several varieties, which, in turn, can be further classified with supplementary features. This results in hundreds of different possibilities for cloud types, which can be quite a thrill for cloud enthusiasts. We will take a look at 10 of the rarer and more interesting clouds you may or may not have come across. A. CLOUDS INDICATING TURBULENCE 1. Altocumulus castellanus – These are a species of mid-level clouds occurring from about 6,500 to 16,500 feet in altitude.