Hypatia Handout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

77 the Incorporation of Girls in the Educational System In

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad de Alcalá POLIS. Revista de ideas y formas políticas de la Antigüedad Clásica 24, 2012, pp. 77-89. THE INCORPORATION OF GIRLS IN THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM IN HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN GREECE Konstantinos Mantas Athens1 From the Hellenistic era onwards, epigraphic evidence proves that some cities in Asia Minor, especially in Ionia and Aeolis, had continued Sappho’s educational tradition. In 2nd cent. BC, in the city of Teos, three ȖȡĮȝȝĮIJȠįȚįȐıțĮȜȠȚ, had been chosen to teach both paides and partenoi 2. At Smyrna and Pergamos, there was a magistrate who was responsible for the supervision of girls3. A very fragmented inscription from Pergamos recorded the curriculum of girls’ schooling: it included penmanship, music and reading as well as epic and elegiac poetry4. Tation, the daughter of Apollonios, is recorded as the winner in the contest for penmanship5. In the 2nd cent, BC, the city of Larissa in Thessaly, honoured a poetess from Smyrna, by granting her the rights of ʌȡȠȟİȞȓĮ, ȑȖțIJȘıȚȢ and ʌȡȠıIJĮıȓĮ6. The city of Tenos honoured Alcinoe from Aetolia, who, according to the restoration of the inscription, had 1 This article is based on a paper which was presented under the title«From Sappho to St Macrina and Hypatia: The changing patterns of women’s education in postclassical antiquity» at the 4th International Conference of SSCIP, 18th of September, 2010. 2 Syll. 3 no 578, ll.9-10. 3 CIG no 3185. 4 Ath. Mitt 37, (1912), no 16. 5 At. Mit. -

The Neoplatonic and Sufi Wisdom

119 ISSN 1648-2662. ACTA ORIENTAUA VILNENSIA. 2002 3 FROM ALEXANDRIA TO HARRAN: THE NEOPLATONIC AND SUFI WISDOM Algis UZOAVINYS Institute of Culture, Philosophy and Art The essay deals with the relationship between the Islamic philosophy and Hellenism. The influence of the Neoplatonic ideas on the early Islamic culture of spirituality is emphasized, while trying to reveal the common archetypal patterns of the Near Eastern and Mediterranean traditions. Without philosophy it is impossible to be perfectly pious. Stobaei Hermetica 11 B.2 Islamic Falsa/ah in the Light of Hellenic Sophia Plotinus used the termsophia (crocllt<X) simply as a synonym of "philosophy", hence restoring its primordial meaning. But falsafah as the continuation of CIItA.ocrocjlt<X is not just Hellenic philoso phy in Islamic guise. In line with Syrian and Mesopotamian translators (be they Sabians, Ori ental Christians or Muslims) the Greek sophia (sapientia) has been connected with Arabic root h-k-m. Sometimes sophia is rendered as 'Urn or even falsafah. Nevertheless, hikmah was chosen as the Arabic equivalent to the Greek termphilosophia, as Franz Rosenthal pointed outl . But philosophy for the Arabs meant the adherence to those philosophic doctrines which they learned chiefly from Neoplatonic commentators of Aristotle as well as Stagirit himself and Alexander Aphrodisias. The termgnosis usually is rendered as ma 'rifah, but many Sufis maintained 'Um as their goal instead of ma'rifah. However, when Sufis spoke of the union (ittihad) they meant an ontic union, not only an epistemic one (ittisal). Therefore, Philip Merlan surmises that it could even be possible that Avicenna sometimes professed both kinds of mysticism, i.e. -

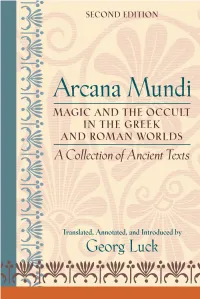

Arcana Mundi : Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds : a Collection of Ancient Texts / Translated, Annotated, and Introduced by Georg Luck

o`o`o`o`o`o SECOND EDITION Arcana Mundi MAGIC AND THE OCCULT IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLDS A Collection of Ancient Texts Translated, Annotated, and Introduced by Georg Luck o`o`o`o`o`o THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS BALTIMORE The first edition of this book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the David M. Robinson Fund and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. ∫ 1985, 2006 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 1985, 2006 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arcana mundi : magic and the occult in the Greek and Roman worlds : a collection of ancient texts / translated, annotated, and introduced by Georg Luck. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. isbn 0-8018-8345-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 0-8018-8346-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Occultism—Greece—History—Sources. 2. Occultism—Rome—History— Sources. 3. Civilization, Classical—Sources. I. Luck, Georg, 1926– bf1421.a73 2006 130.938—dc22 2005028354 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. For Harriet This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Texts ix Preface xiii List of Abbreviations xvii General Introduction: Exploring Ancient Magic 1 I. MAGIC Introduction 33 Texts 93 II. MIRACLES Introduction 177 Texts 185 III. DAEMONOLOGY Introduction 207 Texts 223 IV. DIVINATION Introduction 285 Texts 321 V. -

Rohde's Theory of Relationship Between the Novel and Rhetoric

2020-3673-AJHA-LIT 1 Rohde’s Theory of Relationship Between the Novel and 2 Rhetoric and the Problem of Evaluating the Entire Post- 3 Classical Greek Literature 4 5 The one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the first publication of Rohde’s monograph 6 on the Greek novel is drawing near affording a welcome occasion for raising the big 7 question as to what remains of it today, all the more as the ancient novel, just due to his 8 classical work, has become a major area of research. The aforesaid monograph, 9 considered to be one of the greatest scientific achievements of the eighteenth century, 10 can be justifiably used as a litmus test for ascertaining how efficient methods hitherto 11 employed were or, in other words, whether we are entitled to speak of the continuous 12 progress in research or the opposite is true. Finally, the questions raised in the 13 monograph will turn out to be more important than the results obtained by the author, in 14 so far as the latter, based on his unfinished theses, proved to be very harmful to 15 evaluating both the Greek novel and the entire post-classical Greek literature. In this 16 paper we focus our attention on two major questions raised by the author such as 17 division of the third type of narration in the rhetorical manuals of the classical antiquity 18 and the nature of rhetoric, as expressed in the writings of the major exponents of the 19 Second Sophistic so as to be in a position to point to the way out of aporia, with the 20 preliminary remark that we shall not be able to get the full picture of the Greek novel 21 until the two remaining big questions posed by the author, such as the role played by 22 both Tyche and women in the Greek novel, are fully answered. -

Mark Masterson (Victoria University of Wellington)

THE VISIBILITY OF ‘QUEER’ DESIRE IN EUNAPIUS’ LIVES OF THE PHILOSOPHERS Mark Masterson (Victoria University of Wellington) In this talk, I consider the visibility of male homosexual desire that is excessive of age-discrepant and asymmetrical pederasty within a late fourth-century CE Greek text: Eunapius’ Lives of the Philosophers, section 5.2.3-7 (Civiletti/TLG); Wright 459 (pp. 368-370). I call this desire ‘queer’ and I do so because desire between men was not normative in the way pederastic desire was. I engage in the anachronism of saying the word queer to mark this desire as adversarial to normative modes of desire. Its use is an economical signal as to what is afoot and indeed marks an adversarial mode of reading on my part, a reading against some grains then and now. My claim is that desire between adult men is to be found in this text from the late- Platonic milieu. Plausible reception of Eunapius’ work by an educated readership, which was certainly available, argues for this visibility and it is the foundation for my argument. For it is my assertion that the portion of Eunapius’ text I am discussing today is intertextual with Plato’s Phaedrus (255B-E). In his text, Eunapius shows the philosopher Iamblichus (third to the fourth century) calling up two spirits (in the form of handsome boys) from two springs called, respectively, erōs and anterōs. Since this passage is obviously intertextual with the Phaedrus, interpreting it in light of its relation with Plato makes for interesting reading as the circuits of desire uncovered reveal that Iamblichus is both a subject and object of desire. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE GENRE OF ACTS AND COLLECTED BIOGRAPHY By Sean A. Adams PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2011 2 The thesis is entirely my own work and no portion of it represents work done in collaboration with others. Neither has the dissertation been submitted for any other degree or qualification. Sean A. Adams 3 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that the best genre parallel for the Acts of the Apostles is collected biography. This conclusion is reached through an application of ancient and modern genre theory and a detailed comparison of Acts and collected biographies. Chapter 1 offers prolegomena to this study and further delineates the contours of the thesis. Chapter 2 provides an extensive history of research, not only to provide the context and rationale for the present work, but also to indicate some of the shortcomings of previous investigations and the need for this present study. -

WOMEN's EDUCATION and PUBLIC SPEECH in ANTIQUITY Craig

JETS 50/4 (December 2007) 747–59 WOMEN’S EDUCATION AND PUBLIC SPEECH IN ANTIQUITY craig keener* Were women on average less educated in antiquity than men? Did they enjoy less opportunity, under normal circumstances, for public speech than men did? After noting the relevance of this question for one line of egalitarian interpretation of Paul, I will examine some exceptions to this general rule, philosophic and other ancient intellectual perspectives, the presence of some women in advanced education, women in Jewish education, and women speaking in public. I will conclude that in fact women on average were less educated than men and in particular lacked much access to public speaking roles. An egalitarian conclusion need not follow automatically from such very general premises, but neither should the egalitarian case be dismissed on the specific basis of a denial of the likelihood of these premises. Whether or not one adopts the egalitarian conclusion sometimes drawn from the ancient evidence, the ancient evidence itself need not be in question. i. the relevance of the question Evangelical scholars in good conscience come to differing conclusions on the notorious “gender” passages in Paul, and even those who share similar conclusions may not share all the approaches of their colleagues.1 (Egali- tarians also differ in terms of the circles through which they were intro- duced to the egalitarian position.)2 Nevertheless, one can summarize a general pattern in approaches to background in the debate. As a rule, egalitarians appeal to the cultural setting of the passages to limit their fullest application to a particular cultural setting. -

Edward J. Watts, Hypatia: the Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher

Edward J. Watts, Hypatia: the Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. Pp. xii + 205; 9 illustrations. ISBN: 9780190210038. $29.95. The OUP series Women in Antiquity, which Watts’ book is a part of, aims to provide “compact and accessible introductions” to the life and times its various individul subjects. Watts has accomplished this aim well with his new book. In it, he goes beyond introduction and presents us with a bold new account of this indeed remarkable woman and her achievements. The chief claim of the book is this: we not only do Hypatia (ca. 355–415) a disservice, but more importantly we impoverish our understanding of the late antique world, if we focus on her death at the expense of her life. For much of Hypatia: the life and legend of an Ancient Philosopher, Watts is offering an up to date synthesis, drawing on a wide array of primary sources and recent scholarship. This he does with insight and clarity. But by contextualizing her intellectual and political choices, he puts forth an unprecedentedly strong case that Hypatia represented a publicly engaged and religiously conciliatory style of philosophy which she crafted to serve her unique historical moment (Ch. 1–7). He also supplies one of the most nuanced and compelling narratives to date of her death and the events which led to it (Ch. 8), as well as a new synthesis and interpretation of the way her historical memory became consolidated (Ch. 9–10). The book is at all times very readable, and filled with perceptive characterizations of late antique society and politics. -

Understanding and Dealing with Evil and Suffering

UNDERSTANDING AND DEALING WITH EVIL AND SUFFERING: A FOURTH CENTURY A.D. PAGAN PERSPECTIVE Susanne H. Wallis Thesis submitted for the degree of Masters by Research in Classical Studies School of European Studies and Languages University of Adelaide August 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT DECLARATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................1-14 CHAPTER 1: THE ALTAR OF VICTORY...............................................15-26 Introduction 1. The pagan response Relatio 3 Pro templis Conclusion CHAPTER 2: HEALING THE BODY.......................................................27-60 Introduction 1. Understanding Illness and its Origins Blaming the supernatural The role of astrology: a guide to diagnosis and prognosis The philosopher’s way to good health In the event of plague Mental disturbance: physiological, psychological or philosophical 2. Seeking a cure A Matter of choice Being healthy, staying healthy Healing from the gods: temple medicine Magical protection Iatros: the healer Who will care for the sick? Conclusion CHAPTER 3: EASING THE ANXIOUS MIND........................................61-81 Introduction 1. The forces of fate Human suffering Unseen powers 2. Seeking peace of mind The workings of divination 3. Reading the Signs Astrology Oneiromancy Conclusion CHAPTER 4: PHYSICIAN OF THE SOUL............................................82-112 Introduction 1. Body and Soul Dualism The spiritual athlete Concupiscence of the flesh -

Μελετηματα Contextualizing Late Greek Philosophy

'%- ΚΕΝΤΡΟΝ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΡΩΜΑΪΚΗΣ ΑΡΧΑΙΟΤΗΤΟΣ ΕΘΝΙΚΟΝ ΙΔΡΥΜΑ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ RESEARCH CENTRE FOR GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITY NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION ΜΕΛΕΤΗΜΑΤΑ 54 ELIZABETH KEY FOWDEN and GARTH FOWDEN CONTEXTUALIZING LATE GREEK PHILOSOPHY : " w. ψ^ ATHENS 2008 DIFFUSION DE BOCCARD - 11, RUE DE MEDICIS, 75006 PARIS 3 Η έκδοση αυτή χρηματοδοτήθηκε από το έργο με τίτλο - «Μελέτη και διά χυση τεκμηριωτικών δεδομένων της ιστορίας του Ελληνισμού κατά την Αρχαιότητα» του μέτρου 3.3 του Επιχειρησιακού Προγράμματος «Αντα γωνιστικότητα» - ΕΠΑΝ, πράξη «Αριστεία σε Ερευνητικά Ινστιτούτα» Γ.Γ.Ε.Τ. (2ος Κύκλος). Το Ευρωπαϊκό Ταμείο Περιφερειακής Ανάπτυξης συμμετέχει 75% στις δαπάνες υλοποίησης του ανωτέρω έργου. ISBN 978-960-7905-40-6 © Κέντρον Ελληνικής και Ρωμαϊκής Αρχαιότητος, Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερευνών, 48 Βασ. Κωνσταντίνου, 116 35 Αθήνα. Επεξεργασία κειμένου, εικόνων, εκτύπωση και βιβλιοδεσία: Γραφικές Τέχνες «Γ. Αργυρόπουλος ΕΠΕ» Κ. Παλαμά 13 Καματερό Αθήνα Τηλ. 21023 12 317-Fax21023 13 742 "The school of Plato". Mosaic, Pompeii, 1st c. A.D., Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy. ELIZABETH KEY FOWDEN and GARTH FOWDEN CONTEXTUALIZING LATE GREEK PHILOSOPHY KENTPON ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ KAI ΡΩΜΑΪΚΗΣ ΑΡΧΑΙΟΤΗΤΟΣ ΕΘΝΙΚΟΝ ΙΔΡΥΜΑ ΕΡΕΥΝΩΝ RESEARCH CENTRE FOR GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITY NATIONAL HELLENIC RESEARCH FOUNDATION ΜΕΛΕΤΗΜΑΤΑ 54 DIFFUSION DE BOCCARD -11, RUE DE MEDICIS, 75006 PARIS ELIZABETH KEY FOWDEN and GARTH FOWDEN CONTEXTUALIZING LATE GREEK PHILOSOPHY ATHENS 2008 Contents Abbreviations 9 Preface 11 Acknowledgments 15 PART I: ELEMENTARY EDUCATION IN LATE ANTIQUE PLATONISM by ELIZABETH KEY FOWDEN Introduction 19 1. Learning to live in the world 27 Harmonizing the world 28 Learning by imitating 33 The philosopher priest 3 7 Pythagoras the model student 42 Pythagoras the model teacher 51 The community 55 2. -

Athenian and Alexandrian Neoplatonism and the Harmonization of Aristotle and Plato Studies in Platonism, Neoplatonism, and the Platonic Tradition

Athenian and Alexandrian Neoplatonism and the Harmonization of Aristotle and Plato Studies in Platonism, Neoplatonism, and the Platonic Tradition Edited by Robert M. Berchman (Dowling College and Bard College) John Finamore (University of Iowa) Editorial Board John Dillon (Trinity College, Dublin) – Gary Gurtler (Boston College) Jean-Marc Narbonne (Laval University, Canada) volume 18 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/spnp Athenian and Alexandrian Neoplatonism and the Harmonization of Aristotle and Plato By Ilsetraut Hadot Translated by Michael Chase leiden | boston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hadot, Ilsetraut. Athenian and Alexandrian Neoplatonism and the harmonization of Aristotle and Plato / by Ilsetraut Hadot ; translated by Michael Chase. pages cm. – (Studies in platonism, neoplatonism, and the platonic tradition, ISSN 1871-188X ; volume 18) Includes bibliographical index. ISBN 978-90-04-28007-6 (hardback : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-28159-2 (e-book) 1. Philosophy, Ancient. 2. Plato. 3. Aristotle. 4. Neoplatonism. 5. Alexandrian school. I. Chase, Michael. II. Title. B177.H3313 2015 186'.4–dc23 2014030125 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1871-188x isbn 978-90-04-28007-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28159-2 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Eunapius, Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists (1921) Pp.343-565

0300-0400 – Eunapius Sardianus – De Philosophorum Vitis Eunapius, Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists (1921) pp.343-565. English translation Downloaded form: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/eunapius LIVES OF THE PHILOSOPHERS AND SOPHISTS [Translated by Wilmer Cave WRIGHT] INTRODUCTION Xenophon the philosopher, who is unique among all philosophers in that he adorned philosophy not only with words but with deeds as well (for on the one hand he writes of the moral virtues both in discourses and historical commentaries, while he excelled also in actual achievement; nay more, by means of the examples that he gave he begat leaders of armies; for instance great Alexander never would have become great had Xenophon never been)---- he, I say, asserts that we ought to record even the casual doings of distinguished men. But the aim of my narrative is not to write of the casual doings of distinguished men, but their main achievements. For if even the playful moods of virtue are worth recording, then it would be absolutely impious to be silent about her serious aims. To those who desire to read this narrative it will tell its tale, not indeed with complete certainty as to all matters- ---for it was impossible to collect all the evidence with accuracy----nor shall I separate out from the rest the most illustrious philosophers and orators, but I shall |345 set down for each one his profession and mode of life. That in every case he whom this narrative describes attained to real distinction, the author---- for that is what he aims at----leaves to the judgement of any who may please to decide from the proofs here presented.