Richard Wagner and the Legacy of the Leitmotif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

SM358-Voyager Quartett-Book-Lay06.Indd

WAGNER MAHLER BOTEN DER LIEBE VOYAGER QUARTET TRANSCRIPTED AND RECOMPOSED BY ANDREAS HÖRICHT RICHARD WAGNER TRISTAN UND ISOLDE 01 Vorspiel 9:53 WESENDONCK 02 I Der Engel 3:44 03 II Stehe still! 4:35 04 III Im Treibhaus 5:30 05 IV Schmerzen 2:25 06 V Träume 4:51 GUSTAV MAHLER STREICHQUARTETT NR. 1.0, A-MOLL 07 I Moderato – Allegro 12:36 08 II Adagietto 11:46 09 III Adagio 8:21 10 IV Allegro 4:10 Total Time: 67:58 2 3 So geht das Voyager Quartet auf Seelenwanderung, überbringt klingende BOTEN DER LIEBE An Alma, Mathilde und Isolde Liebesbriefe, verschlüsselte Botschaften und geheime Nachrichten. Ein Psychogramm in betörenden Tönen, recomposed für Streichquartett, dem Was soll man nach der Transkription der „Winterreise“ als Nächstes tun? Ein Medium für spirituelle Botschaften. Die Musik erhält hier den Vorrang, den Streichquartett von Richard Wagner oder Gustav Mahler? Hat sich die Musikwelt Schopenhauer ihr zugemessen haben wollte, nämlich „reine Musik solle das nicht schon immer gewünscht? Geheimnisse künden, die sonst keiner wissen und sagen kann.“ Vor einigen Jahren spielte das Voyager Quartet im Rahmen der Bayreuther Andreas Höricht Festspiele ein Konzert in der Villa Wahnfried. Der Ort faszinierte uns über die Maßen und so war ein erster Eckpunkt gesetzt. Die Inspiration kam dann „Man ist sozusagen selbst nur ein Instrument, auf dem das Universum spielt.“ wieder durch Franz Schubert. In seinem Lied „Die Sterne“ werden eben diese Gustav Mahler als „Bothen der Liebe“ besungen. So fügte es sich, dass das Voyager Quartet, „Frauen sind die Musik des Lebens.“ das sich ja auf Reisen in Raum und Zeit begibt, hier musikalische Botschaften Richard Wagner versendet, nämlich Botschaften der Liebe von Komponisten an ihre Musen. -

Zwischen Nottaufe Und Nottrauung – Einblicke in Das Leben Felix Mottls

Clarissa Höschel Zwischen Nottaufe und Nottrauung – Einblicke in das Leben Felix Mottls . Eine Hommage zu seinem 160. Geburtstag In der Münchener Musikgeschichte hat er längst seinen festen Platz – der aus Unter St. Veit (Wien) stammende Felix Mottl (1856–1911), der von 1904 bis zu seinem Tod als Generalmusikdirektor an der Isar wirkte. Der Mensch hinter dem Musiker ist hingegen nur wenigen bekannt; selbst die anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages erschienene Biografe1 porträtiert in erster Linie den Musi- ker. Auch anlässlich seines 100. Todestages (2011) wurde, wenn überhaupt, an den Generalmusikdirektor erinnert – Anlass genug, einige Facetten des Menschen und Mannes Felix Mottl vorzustellen. Gelingen kann ein solches Unterfangen anhand der tagebuchartigen Aufzeich- nungen, die Mottl 1873 be- gonnen hat und die heute in der Bayerischen Staats- bibliothek in München als Teil des Nachlasses Felix Abb. 1: Felix Mottl um 1900. Foto: Max Stufer Kunstverlag. Mona censia. Literaturarchiv und Bibliothek München (Sign. P / a 1129). 1 Frithjof Haas, Der Magier am Dirigentenpult, Karlsruhe 2006. Eine Rezension der Ver- fasserin fndet sich in Musik in Bayern 72 / 73 (2007 / 08), S. 248–254. 157 Clarissa Höschel Mottls aufewahrt werden.2 Mottl hat diese Aufzeichnungen zwar bis kurz vor seinem Tod geführt, doch sind sie nichts weniger als bewusst für die Nachwelt Hinterlassenes. Soweit sie im Original vorliegen, weisen sie einen sehr eigentümlichen Stil auf, denn sie bestehen, vor allem bis zu seiner New- York-Reise (1903), aus mit stichpunktartigen Notizen vollgeschriebenen Ta- schenkalendern, die meist über mehrere Jahre hinweg verwendet wurden. Mottls Schrif ist klein und unleserlich, seine Einträge sind in aller Regel kurz und knapp und bestehen of nur aus einzelnen Worten, die durch Punk- te getrennt sind. -

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please Note That This Lesson Works Best Post-Show

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please note that this lesson works best post-show Educator should choose which female character to focus on based on the opera(s) the group has attended. See below for the list of female characters in each opera: Das Rheingold: Fricka, Erda, Freia Die Walküre: Brunhilde, Sieglinde, Fricka Siegfried: Brunhilde, Erda Götterdämmerung: Brunhilde, Gutrune GRADE LEVELS 6-12 TIMING 1-2 periods PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Educator should be somewhat familiar with the female characters of the Ring AIM OF LESSON Compare and contrast the actual women in Wagner’s life to the female characters he created in the Ring OBJECTIVES To explore the female characters in the Ring by studying Wagner’s relationship with the women in his life CURRICULAR Language Arts CONNECTIONS History and Social Studies MATERIALS Computer and internet access. Some preliminary resources listed below: Brunhilde in the “Ring”: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brynhildr#Wagner's_%22Ring%22_cycle) First wife Minna Planer: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minna_Planer) o Themes: turbulence, infidelity, frustration Mistress Mathilde Wesendonck: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Wesendonck) o Themes: infatuation, deep romantic attachment that’s doomed, unrequited love Second wife Cosima Wagner: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosima_Wagner) o Themes: devotion to Wagner and his works; Wagner’s muse Wagner’s relationship with his mother: (https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/richard-wagner-392.php) o Theme: mistrust NATIONAL CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.9 STANDARDS/ Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a STATE STANDARDS historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors of fiction use or alter history. -

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23Rd to 27Th September 2020

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23rd to 27th September 2020 Imprint The Richard Wagner Congress 2020 Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn e.V. programme Andreas Loesch (Vorsitzender) John Peter (stellv. Vorsitzender) was created in collaboration with Zanderstraße 47, 53177 Bonn Tel. +49-(0)178-8539559 [email protected] Organiser / booking details ARS MUSICA Musik- und Kulturreisen GmbH Bachemer Straße 209, 50935 Köln Tel: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 00 Fax: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 01 [email protected] RICHARD-WAGNER-VERBAND BONN E.V. and is sponsored by Image sources frontpage from left to right, from top to bottom - Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Deutsche Post / Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - StadtMuseum Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Beethovenhaus Bonn - Stadt Königswinter - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Stadtmuseum Siegburg - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn Current information about the program backpage - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn rwv-bonn.de/kongress-2020 Congress Programme for all Congress days 2 p.m. | Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Dear Members of the Richard Wagner Societies, dear Friends of Richard Wagner’s Music, Conference Hotel Hilton Richard Wagner – en miniature Symposium: »Beethoven, Wagner and the political “Welcome” to the Congress of the International Association of Richard Wagner Societies in 2020, commemorating Ludwig “Der Meister” depicted on stamps movements of their time « (simultaneous translation) van Beethoven’s 250th birthday worldwide. Richard Wagner appreciated him more than any other composer in his life, which Prof. Dr. Dieter Borchmeyer, PD Dr. Ulrike Kienzle, is why the Congress in Bonn, Beethoven’s hometown, is going to centre on “Beethoven and Wagner”. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

The German Romantic Movement

The German Romantic Movement Start date 27 March 2020 End date 29 March 2020 Venue Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge CB23 8AQ Tutor Dr Robert Letellier Course code 1920NRX040 Director of ISP and LL Sarah Ormrod For further information on this Zara Kuckelhaus, Fleur Kerrecoe course, please contact the Lifelong [email protected] or 01223 764637 Learning team To book See: www.ice.cam.ac.uk or telephone 01223 746262 Tutor biography Robert Ignatius Letellier is a lecturer and author and has presented some 30 courses in music, literature and cultural history at ICE since 2002. Educated in Grahamstown, Salzburg, Rome and Jerusalem, he is a member of Trinity College (Cambridge), the Meyerbeer Institute Schloss Thurmau (University of Bayreuth), the Salzburg Centre for Research in the Early English Novel (University of Salzburg) and the Maryvale Institute (Birmingham) as well as a panel tutor at ICE. Robert's publications number over 100 items, including books and articles on the late seventeenth-, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novel (particularly the Gothic Novel and Sir Walter Scott), the Bible, and European culture. He has specialized in the Romantic opera, especially the work of Giacomo Meyerbeer (a four-volume English edition of his diaries, critical studies, and two analyses of the operas), the opera-comique and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Operetta, the Romantic Ballet and Ludwig Minkus. He has also worked with the BBC, the Royal Opera House, Naxos International and Marston Records, in the researching and preparation of productions. University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course programme Friday Please plan to arrive between 16:30 and 18:30. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Copyright © 2012 by Martin M. Van Brauman THEOLOGICAL AND

THEOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL ANTI-SEMITISM MANIFESTING INTO POLITICAL ANTI-SEMITISM MARTIN M. VAN BRAUMAN The Lord appeared to Solomon at night and said to him I have heard your prayer and I have chosen this place to be a Temple of offering for Me. If I ever restrain the heavens so that there will be no rain, or if I ever command locusts to devour the land, or if I ever send a pestilence among My people, and My people, upon whom My Name is proclaimed, humble themselves and pray and seek My presence and repent of their evil ways – I will hear from Heaven and forgive their sin and heal their land. 2 Chronicles 7:12-14. Political anti-Semitism represents the ideological weapon used by totalitarian movements and pseudo-religious systems.1 Norman Cohn in Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion wrote that during the Nazi years “the drive to exterminate the Jews sprang from demonological superstitions inherited from the Middle Ages.”2 The myth of the Jewish world-conspiracy developed out of demonology and inspired the pathological fantasy of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was used to stir up the massacres of Jews during the Russian civil war and then was adopted by Nazi ideology and later by Islamic theology.3 Most people see anti-Semitism only as political and cultural anti-Semitism, whereas the hidden, most deeply rooted and most dangerous source of the evil has been theological anti-Semitism stemming historically from Christian dogma and adopted by and intensified with -

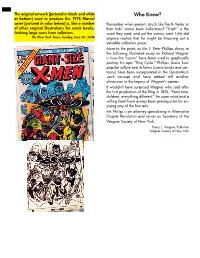

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought.