A Historical and Contextual Analysis of Soviet and Russian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformación Del Significado Del Feminismo. Análisis Del Discurso

Transformación del Significado del Feminismo. Análisis del Discurso Presente en la Marcha del 8 de marzo del 2020 en la Ciudad de Quito Fátima C. Holguín Herrera Facultad de Comunicación Lingüística y Literatura Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Trabajo de Titulación previo a la Obtención del Título de Licenciado(a) en Comunicación con Mención en Periodismo para Radio Prensa y Televisión Bajo la dirección de Dr. Fernando Albán Quito, Ecuador, 2020 1 2 Resumen En el presente trabajo se usa el análisis del discurso, como herramienta de investigación para examinar el discurso presentado en la marcha del ocho de marzo del dos mil veinte. El mismo que tienen que ver un concepto de emancipación ¿qué conlleva este concepto de emancipación? Supone que hay un estado de opresión, subordinación del cual debemos liberarnos, es justamente de este concepto que hace uso, en este caso, el feminismo, aquí analizado; toma la noción de emancipación del sistema opresor que oprimiría a las mujeres, incluso a los hombres, por lo que hay que liberarse de este sistema denominado patriarcado el que estaría inherentemente anclado al neoliberalismo, capitalismo como se menciona. Palabras clave: feminismo, marxismo, ideología, patriarcado, genero, opresión, violencia. 3 Tabla de Contenido INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................................... 6 METODOLOGÍA ..................................................................................................................... 8 EL PROBLEMA -

THE BLACK MARKET for SOCIAL MEDIA MANIPULATION NATO Stratcom COE Singularex

COUNTERING THE MALICIOUS USE OF SOCIAL MEDIA THE BLACK MARKET FOR SOCIAL MEDIA MANIPULATION NATO StratCom COE Singularex ISBN 978-9934-564-31-4 ISBN: 978-9934-564-31-4 Authors: NATO StratCom COE Research: Singularex Project manager: Sebastian Bay Text editor: Anna Reynolds Design: Kārlis Ulmanis Riga, November 2018 NATO STRATCOM COE 11b Kalciema iela Riga LV1048, Latvia www.stratcomcoe.org Facebook/stratcomcoe Twitter: @stratcomcoe Singularex is a Social Media Intelligence and Analytics company based in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Website: www.singularex.com Email: [email protected] This publication does not represent the opinions or policies of NATO. © All rights reserved by the NATO StratCom COE. Reports may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or publicly displayed without reference to the NATO StratCom COE. The views expressed here are solely those of the author in his private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of NATO StratCom COE. NATO StratCom COE does not take responsibility for the views of authors expressed in their articles. Social media manipulation is undermining democracy, but it is also slowly undermining the social media business model. Introduction Around the turn of the decade, when the popularity of social media sites was really beginning to take off, few people noticed a secretly burgeoning trend — some users were artificially inflating the number of followers they had on social media to reap financial benefits. Even fewer noticed that organisations such as the Internet Research Agency were exploiting these new techniques for political gain. Only when this innovation in information warfare was deployed against Ukraine in 2014 did the world finally become aware of a practice that has now exploded into federal indictments,1 congressional hearings,2 and a European Union Code of Practice on Disinformation.3 At the heart of this practice, weaponised by states and opportunists alike, is a flourishing black market where buyers and sellers meet to trade in clicks, likes, and shares. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Contemporary Art in the Regions of Russia: Global Trends and Local Projects

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 10 (2016 9) 2413-2426 ~ ~ ~ УДК 7.01 Contemporary Art in the Regions of Russia: Global Trends and Local Projects Dmitrii V. Galkin* and Anastasiia Iu. Kuklina National Research Tomsk State University 36 Lenina Str., Tomsk, 634050, Russia Received 21.04.2016, received in revised form 09.06.2016, accepted 19.08.2016 The authors deal with the problem of the development of contemporary art in the regions of Russia in the context of global projects and institutions, establishing ‘the rules of the game’ in the field of contemporary culture. The article considers the experience of working with contemporary art within the framework of the National Centre for Contemporary Arts and other organizations. So-called Siberian ironic conceptualism is considered as an example of original regional aesthetics. The article concludes that the alleged problem can be solved in the framework of specific exhibition projects and curatorial decisions, which aim at finding different forms of meetings (dialogue, conflict, addition) of a regional identity and global trends. Keywords: contemporary art, National Center for Contemporary Arts, curatorial activities, regional art. This article was prepared with the support of the Siberian Branch of the National Centre for Contemporary Arts. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-10-2413-2426. Research area: art history. The growing interest of researchers and also intends to open a profile branch in Moscow. the public in the dynamic trends and issues But this is an example of the past three years. of contemporary art in Russia is inextricably There are more historically important and long- linked with the development of various projects standing examples. -

Recent Trends in Online Foreign Influence Efforts

Recent Trends in Online Foreign Influence Efforts Diego A. Martin, Jacob N. Shapiro, Michelle Nedashkovskaya Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs Princeton University Princeton, New Jersey, United States E-mail: [email protected] Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Foreign governments have used social media to influence politics in a range of countries by promoting propaganda, advocating controversial viewpoints, and spreading disinformation. We analyze 53 distinct foreign influence efforts (FIEs) targeting 24 different countries from 2013 through 2018. FIEs are defined as (i) coordinated campaigns by one state to impact one or more specific aspects of politics in another state (ii) through media channels, including social media, (iii) by producing content designed to appear indigenous to the target state. The objective of such campaigns can be quite broad and to date have included influencing political decisions by shaping election outcomes at various levels, shifting the political agenda on topics ranging from health to security, and encouraging political polarization. We draw on more than 460 media reports to identify FIEs, track their progress, and classify their features. Introduction Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) have changed the way people communi- cate about politics and access information on a wide range of topics (Foley 2004, Chigona et al. 2009). Social media in particular has transformed communication between leaders and voters by enabling direct politician-to-voter engagement outside traditional avenues, such as speeches and press conferences (Ott 2017). In the 2016 U.S. presidential election, for example, social media platforms were more widely viewed than traditional editorial media and were central to the campaigns of both Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton and Republican candidate Donald Trump (Enli 2017). -

The Unfinished War

#3 (85) March 2015 Can Ukraine survive the next Mobilization campaign: Reasons behind the sharp winter without Russian gas myths and reality devaluation of the hryvnia CRIMEA: THE UNFINISHED WAR WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION |CONTENTS BRIEFING The New Greece in the East:Without a much bigger, long- Branding the Emperor: term investment program, Ukraine’s economy will continue to New implications of Nadiya flounder Savchenko’s case for Vladimir Putin 31 Let Bygones be Bygones: Attempts to preserve the Russian 4 market for Ukrainian exporters by making concessions in EU- Leonidas Donskis on the murder Ukraine Association Agreement hurt Ukraine’s trade prospects of Boris Nemtsov 32 6 FOCUS SECURITY Kyiv – Crimea: the State of Fear of Mobilization: Uncertainty Myths and Reality Has Ukraine learned the An inside look at how lessons of occupation? the army is being formed 8 34 Maidan of Foreign Affairs’ NearestR ecruiting Station: Andrii Klymenko on Serhiy Halushko, Deputy Head Russia’s troops and nuclear of Information Technology weapons, population substitution and techniques to crush protest Department of the Ministry of Defense, talks about practical potential on the occupied peninsula aspects of the mobilization campaign 12 38 Freedom House Ex-President David Kramer on human rights SOCIETY abuses in Crimea, the threat of its militarization and President Catching Up With Obama’s reluctance in arming Ukraine the Future: Will 14 the IT industry drive economic POLITICS development -

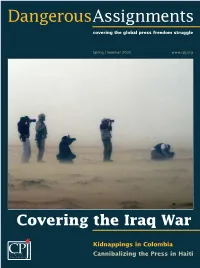

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN Introduction by Susan Buck-Morss and Victor Tupitsyn the Museological Unconscious

The Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN introduction by Susan Buck-Morss and Victor Tupitsyn The Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN The Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN Communal (Post)Modernism in Russia THE MIT PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS LONDON, ENGLAND © 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email special_sales@ mitpress.mit .edu or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Sabon and Univers by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia. Printed and bound in Spain. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tupitsyn, Viktor, 1945– The museological unconscious : communal (post) modernism in Russia / Victor Tupitsyn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-20173-5 (hard cover : alk. paper) 1. Avant-garde (Aesthetics)—Russia (Federation) 2. Dissident art—Russia (Federation) 3. Art and state— Russia (Federation) 4. Art, Russian—20th century. 5. Art, Russian—21st century. I. Title. N6988.5.A83T87 2009 709.47’09045—dc22 2008031026 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Margarita CONTENTS PREFACE ix 1 Civitas Solis: Ghetto as Paradise 13 INTRODUCTION 1 2 Communal (Post)Modernism: 33 SUSAN BUCK- MORSS A Short History IN CONVERSATION 3 Moscow Communal Conceptualism 101 WITH VICTOR TUPITSYN 4 Icons of Iconoclasm 123 5 The Sun without a Muzzle 145 6 If I Were a Woman 169 7 Pushmi- pullyu: 187 St. -

The Russian Vertikal: the Tandem, Power and the Elections

Russia and Eurasia Programme Paper REP 2011/01 The Russian Vertikal: the Tandem, Power and the Elections Andrew Monaghan Nato Defence College June 2011 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/ speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication. REP Programme Paper. The Russian Vertikal: the Tandem, Power and the Elections Introduction From among many important potential questions about developments in Russian politics and in Russia more broadly, one has emerged to dominate public policy and media discussion: who will be Russian president in 2012? This is the central point from which a series of other questions and debates cascade – the extent of differences between President Dmitry Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin and how long their ‘Tandem’ can last, whether the presidential election campaign has already begun and whether they will run against each other being only the most prominent. Such questions are typically debated against a wider conceptual canvas – the prospects for change in Russia. Some believe that 2012 offers a potential turning point for Russia and its relations with the international community: leading to either the return of a more ‘reactionary’ Putin to the Kremlin, and the maintenance of ‘stability’, or another term for the more ‘modernizing’ and ‘liberal’ Medvedev. -

Politicians Comment on Ukraine's Achievements Over the Past Decade

INSIDE:• Ukraine’s steps“TEN to independence: YEARS OFa timeline INDEPENDENT — page 7 UKRAINE” • Academic and professional perspective: an interview — page 8 • Kyiv students perspective — page 6 Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX HE KRAINIANNo. 34 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 26, 2001 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine PoliticiansT commentU on Ukraine’s Third UkrainianW World Forum held in Kyiv achievements over the past decade Criticizes Kuchma, produces little progress by Roman Woronowycz obvious one. We believed the question by Roman Woronowycz Ukrainian government to develop a policy Kyiv Press Bureau was still worth asking because it gave us Kyiv Press Bureau of immigration and reintegration of the an insight into how the political leaders diaspora into Ukrainian society and the KYIV – If you asked well over a view that which has transpired over the KYIV – The Third World Forum of lack of cohesiveness and cooperation dozen politicians what they think is the last decade in this country. Ukrainians opened on August 18 with among the legislative and executive greatest achievement of 10 years of The Ukrainian politicians that The much pomp, high expectations and calls branches of power in Ukraine. Ukrainian independence, you would Weekly questioned come from various for consolidation of the Ukrainian nation The resolution blames the failure to think the replies would be varied, accent- points on the Ukrainian political horizon on the eve of the 10th anniversary celebra- complete democratic and economic ing various nuances in the political, eco- and have either been near the top of the tion of the country’s independence. -

Reichskommissariat Ukraine from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Reichskommissariat Ukraine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia During World War II, Reichskommissariat Ukraine (abbreviated as RKU), was the civilian Navigation occupation regime of much of German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of Reichskommissariat Ukraine Main page modern Belarus and pre-war Poland). Between September 1941 and March 1944, the Reichskommissariat of Germany Contents Reichskommissariat was administered by Reichskommissar Erich Koch. The ← → Featured content administration's tasks included the pacification of the region and the exploitation, for 1941–1944 Current events German benefit, of its resources and people. Adolf Hitler issued a Führer Decree defining Random article the administration of the newly occupied Eastern territories on 17 July 1941.[1] Donate to Wikipedia Before the German invasion, Ukraine was a constituent republic of the USSR, inhabited by Ukrainians with Russian, Polish, Jewish, Belarusian, German, Roma and Crimean Tatar Interaction minorities. It was a key subject of Nazi planning for the post-war expansion of the German Flag Emblem state and civilization. Help About Wikipedia Contents Community portal 1 History Recent changes 2 Geography Contact Wikipedia 3 Administration 3.1 Political figures related with the German administration of Ukraine Toolbox 3.2 Military commanders linked with the German administration of Ukraine 3.3 Administrative divisions What links here 3.3.1 Further eastward expansion Capital Rowno (Rivne) Related changes 4 Demographics Upload file Languages German (official) 5 Security Ukrainian Special pages 6 Economic exploitation Polish · Crimean Tatar Permanent link 7 German intentions Government Civil administration Page information 8 See also Reichskommissar Data item 9 References - 1941–1944 Erich Koch Cite this page 10 Further reading Historical era World War II 11 External links - Established 1941 Print/export - Disestablished 1944 [edit] Create a book History Download as PDF Population This section requires expansion. -

The War Correspondent

The War Correspondent The War Correspondent Fully updated second edition Greg McLaughlin First published 2002 Fully updated second edition first published 2016 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Greg McLaughlin 2002, 2016 The right of Greg McLaughlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3319 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3318 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1758 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1760 6 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1759 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the European Union and United States of America Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 PART I: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 2 The War Correspondent: Risk, Motivation and Tradition 9 3 Journalism, Objectivity and War 33 4 From Luckless Tribe to Wireless Tribe: The Impact of Media Technologies on War Reporting 63 PART II: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND THE MILITARY 5 Getting to Know Each Other: From Crimea to Vietnam 93 6 Learning and Forgetting: From the Falklands to the Gulf 118 7 Goodbye Vietnam Syndrome: The Embed System in Afghanistan and Iraq 141 PART III: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND IDEOLOGICAL FRAMEWORKS 8 Reporting the Cold War and the New World Order 161 9 Reporting the ‘War on Terror’ and the Return of the Evil Empire 190 10 Conclusions: ‘Telling Truth To Power’ – the Ultimate Role of the War Correspondent? 214 1 Introduction William Howard Russell is widely regarded as one of the first war cor- respondents to write for a commercial daily newspaper.