Tift College, Georgia Baptists' Separate College for Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

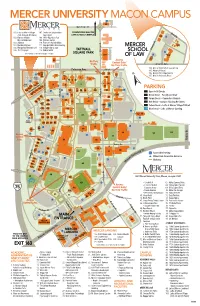

CAMPUS 16 Oglethorpe St

MERCER UNIVERSITY MACON CAMPUS 16 Oglethorpe St. 101. Lofts at Mercer Village 107. Center for Collaborative DOWNTOWN MACON Bond St (2nd, 3rd and 4th floors) Journalism LAW SCHOOL CAMPUS 116 102. Barnes & Noble 108. JAG’s Pizzeria & Pub . Mercer Bookstore 109. Z Beans Coffee . 103. Subway 110. Francar’s Buffalo Wings St 104. Nu-Way Weiners 111. Georgia Public Broadcasting ge 115 105. Margaritas Mexican Grill 112. Indigo Salon & Spa MERCER an 106. The Telegraph 113. WMUB/ESPN TATTNALL Or College St. College SCHOOL Front entrances are wheelchair accessible. SQUARE PARK 100 OF LAW 114 117 42 Access No Thru Control Gate/ Traffic No Thru Traffic Georgia Ave. 114. Mercer University School of Law Coleman Ave. Ash St. 115. Woodruff House 112 116. Orange Street Apartments 113 111 17 18 19 7 6a 117. Mercer University Press Retail 110 1 55 Parking 6 2 6b 5 4 Retail 109 3 20 108 8 9 Parking 101 102 56 107 103 PARKING 106 101 10 12 13 14 15 57 Montpelier104 Ave. Linden Ave. Open to All Decals 105 11 58 Green Decal – Faculty and Staff Adams St. 66 St. College 22 65 Purple Decal – Commuter Students 68 60 64 61 21 Red Decal – Campus Housing Residents 67 69 59 43 Yellow Decal – Lofts at Mercer Village/Tattnall 70 71 62 Blue Decal – Lofts at Mercer Landing 73 25 27 28 23 72 24 26 74 75 76 77 63 Visitor Parking 78 79 80 81 31 32 82 29 30 83 34 54 Access 53 Control 33 Gate 84 44 35 St. -

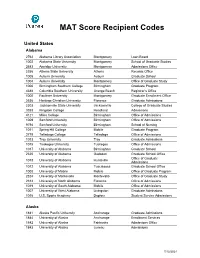

MAT Score Recipient Codes

MAT Score Recipient Codes United States Alabama 2762 Alabama Library Association Montgomery Loan Board 1002 Alabama State University Montgomery School of Graduate Studies 2683 Amridge University Montgomery Admissions Office 2356 Athens State University Athens Records Office 1005 Auburn University Auburn Graduate School 1004 Auburn University Montgomery Office of Graduate Study 1006 Birmingham Southern College Birmingham Graduate Program 4388 Columbia Southern University Orange Beach Registrar’s Office 1000 Faulkner University Montgomery Graduate Enrollment Office 2636 Heritage Christian University Florence Graduate Admissions 2303 Jacksonville State University Jacksonville College of Graduate Studies 3353 Kingdom College Headland Admissions 4121 Miles College Birmingham Office of Admissions 1009 Samford University Birmingham Office of Admissions 9794 Samford University Birmingham School of Nursing 1011 Spring Hill College Mobile Graduate Program 2718 Talladega College Talladega Office of Admissions 1013 Troy University Troy Graduate Admissions 1015 Tuskegee University Tuskegee Office of Admissions 1017 University of Alabama Birmingham Graduate School 2320 University of Alabama Gadsden Graduate School Office Office of Graduate 1018 University of Alabama Huntsville Admissions 1012 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa Graduate School Office 1008 University of Mobile Mobile Office of Graduate Program 2324 University of Montevallo Montevallo Office of Graduate Study 2312 University of North Alabama Florence Office of Admissions 1019 University -

MERCER UNIVERSITY Catalog 2008-2009

MERCER UNIVERSITY Catalog 2008-2009 CECIL B. DAY GRADUATE AND PROFESSIONAL CAMPUS Stetson School of Business and Economics Tift College of Education College of Continuing and Professional Studies McAfee School of Theology Georgia Baptist College of Nursing _______________________________ Atlanta, Georgia 30341 Table of Contents Page Calendar . .5 Directory . .8 The University . .11 Special Programs . .22 Campus Life . .27 Financial Information . .35 Academic Information . .49 Undergraduate Studies Stetson School of Business and Economics . .63 Undergraduate Programs Policies and Procedures . .65 Admission . .65 Other Policies and Procedures . .68 Degree Requirements . .74 Curriculum . .75 Courses of Instruction . .82 College of Continuing and Professional Studies . .95 Degree Programs . .97 Course Descriptions . .107 Georgia Baptist College of Nursing . .125 Graduate Studies General Information . .127 Stetson School of Business and Economics . .131 Master of Business Administration . .137 Master of Business Administration/Doctor of Pharmacy . .139 Master of Business Administration/Master of Divinity . .140 Executive Master of Business Administration . .149 Master of Accountancy . .152 Tift College of Education . .155 Master of Arts in Teaching Degree . .159 Master of Education Degree . .167 Teacher Education Programs Early Childhood Education . .168 Middle Grades Education . .170 Secondary Education . .172 Reading . .174 Educational Leadership Program . .176 TABLE OF CONTENTS / 3 Specialist in Education Degree . .183 Doctor of Philosophy Degree . .184 Course Descriptions . .188 College of Continuing and Professional Studies . .205 Master of Science in Counseling . .207 Master of Science/School Counseling . .210 Post-degree Certificate in Professional Counseling . .215 Master of Science in Counseling/Master of Divinity in Pastoral Care and Counseling . .217 Master of Science in Public Safety Leadership . .218 Course Descriptions . -

An Analytical Survey of Fine Arts Departments in Selected Southern Baptist Colleges

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 An Analytical Survey of Fine Arts Departments in Selected Southern Baptist Colleges. Grady Murrell Harper Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Harper, Grady Murrell, "An Analytical Survey of Fine Arts Departments in Selected Southern Baptist Colleges." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1595. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1595 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-242 HARPER, Grady Murrell, 1932- AN ANALYTICAL SURVEY OF FINE ARTS DEPARTMENTS IN SELECTED SOUTHERN BAPTIST COLLEGES. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1969 Education, administration University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN ANALYTICAL SURVEY OF FINE ARTS DEPARTMENTS IN SELECTED SOUTHERN BAPTIST COLLEGES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Education by Grady Murrell Harper B.A., Louisiana College, 1955 M.Ed., Northwestern State College of Louisiana, 1957 May, 1969 ii ACKNOWL EDGM ENTS This study has been made with the counsel, interest, cooperation and assistance of many persons. The writer wishes to acknowledge his special gratitude and indebtedness to Dr. -

Colleges of Arts and Sciences

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR . BUREAU OF EDUCATION BUI.F.TiN, 1918, No. 30 RESOURCES AND STANDARDS of COLLEGES OF ARTS AND SCIENCES REPORT OF A COMMITTEE REPRESENTING THE ASSOCIATIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS Prepared by SAMUEL PAUL CAPEN SECRETARY WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, . A D DITIONA I. CO 1'1 Es 07 THIS PUDLICATION MAY IIEPROCURED FROM TIIE SUCERINTESDENT OFDOCUMENTS DoVERNMENT PRINTINO OFFICE . WASILINGToN, P.C. AT 10 CENTS COPY CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittal 5 Members of the committee on higher educational statistics 7 A critical study of college and university resources 7 Special inquiry to colleges of arts and sciences 8 Subcommittee on definition of college standards 14 Suggested requirements for a successful college of arts andsciences 15 Table 1.Colleges of arts and sciencesPart I: Professorsand instructors . 18 Table 1.Colleges of arts and sciencesPart II: Students,expenditures, and receipts 31 Financial foundation 44 Table..Productive endowment, income, and debt e- 44 Table 3.Income and amount spent for salaries ofcollege teachers 48 Number of departments 51. Table 4.Institutions having.11 specifieddepartmeilor feu-er 52 Size of faculty . 53 Table 5.Nurober of faculty members devoting fulltime to college instruc- tionNumber of college students 54 Separation of college and preparatory department 57 Table 6.Number of faculty members giving parttime to preparatory work.. 58 Advanced degrees of faculty members 59 Table 7.Number of faculty members holdingbachelor's degree, master's degree, and doctor's degree (excluding honorarydegreeli) 60 Table 8.,Number of teaching hours of facultymembers 64 Table 9.Requirements for admission andgraduation 68 Table 10.Expenditures for library andlaboratories 70. -

Undergraduate Catalog Pages 426-457

THE FACULTY (verified at press time, April 2003) The first date in the entry indicates the year of initial employment as a regular, full- time faculty member; the second date is the year of promotion to present rank at Valdosta State University. Faculty members with temporary or part-time appointments are not listed. An asterisk * indicates membership on the Graduate Faculty. *ADLER, Brian U. ............................................. Professor of English and Director of the University Honors Program B.A., University of South Carolina; M.A. University of Georgia; Ph.D., University of Tennessee; 1994; 1999. ALBOUM, Scott H. ......................... Assistant Professor of Communication Arts B.S.C., M.F.A., University of Miami; 2002. *ALDINGER, Robert Thomas ..................................Professor of Political Science B.A., Michigan State University; M.P.A., University of Oklahoma; D.P.A., University of Georgia; 1988; 2001. *ALLEN, Lee M. ........................................................Professor of Political Science B.A., M.A. University of Nevada, Las Vegas; J.D., University of Houston; Ph.D., University of Utah; 1993; 1998. *ALLEN, Ralph C. .................................... Professor of Marketing and Economics and Head of Department B.S., Emory University; M.S., Ph.D., Georgia State University; 1982; 1992. *ALLY, Harry P................................................................................ Professor of Art B.F.A., Texas Christian University; M.F.A., North Texas State University; 1985; 1994. *ANDERSON, Patricia ........................ Professor of Adult and Career Education B.B.A., University of Pennsylvania; M.Ed., Ed.D., Temple University; 1988; 1999. ANDREW, Diane .................................... Assistant Professor of Special Education and Communication Disorders B.S.Ed., M.S.T., University of Wisconsin; 1982; 1986. ANDREWS, AliceE. ............................... Assistant Professor of Special Education and Communication Disorders B.S.E., M.A., Northeast Missouri State University; 1989; 1993. -

Catalog 1924-1925

Georgia College Knowledge Box Georgia College Catalogs Special Collections Spring 1924 catalog 1924-1925 Georgia College and State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/catalogs Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia College and State University, "catalog 1924-1925" (1924). Georgia College Catalogs. 82. https://kb.gcsu.edu/catalogs/82 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia College Catalogs by an authorized administrator of Knowledge Box. The Mansion (The President’s Residence) Erected 1838, and used for Thirty Years as the Residence of the Governors of Georgia; now the Property of the Georgia State College for Women v j * j BULLETIN VOL. XI____________ JANUARY, .q26________________ No_ 3 3 5 o L ! GEORGIA STATE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN MILLEDGEVILLE, GEORGIA . CATALOGUE NUMBER 1924-1925 Published monthly by the Georgia State College for Women, Milledgeville, Georgia, and entered at the post office at Milledgeville, Georgia, as second class matter. MAP SHOWING LOCATION OF THE COLLEGE AND RAILROADS LEAD ING TO MILLEDGEVILLE CONTENTS. CO LLEGE C A LEN D A R ................................................................................... 8 P A R T 1. O FFICERS OF TH E C O LLEG E.............................................9-30 Board of Directors.......................................................................... 10 Board of Visitors............................................................................ -

Student Achievement Numbers Are Soaring

The FALL 2020 A PUBLICATION OF MERCER UNIVERSITY • WWW.MERCER.EDU BUILT FOR STUDENT SUCCESS Student Achievement Numbers Are Soaring — See Story on Page 14 STEMBRIDGE OurLens CENTER FOR InMercer’s new Stembridge Center for Student Success is named for Willard D. “Bill” Stembridge (right), a 1968 graduate of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and generous supporter of the University. “Bill has been as supportive a graduate and as active a cheerleader of one’s alma STUDENT mater as I’ve seen during my 30 years in higher education,” said Mercer President William D. Underwood (left). “Whether it’s attending fine arts or theatrical events, participating in lectures, or cheering at athletics events, SUCCESS Bill is everywhere having anything to do with this University.” DEDICATED Mercer has opened a new facility on the Macon campus fulfilling a more-than-two- decade dream at the University to provide a “one-stop shop” for Mercerians combining vital student support functions. The University on Feb. 17 dedicated the Stembridge Center for Student Success, which houses the offices of Student Success, Student Financial Planning, Registrar, Bursar and Student Loans. “By putting those offices all in the same building, no matter which one students go to, if they chose the wrong one, it’s only down the hall or up a floor or down a floor,” said Dr. James Netherton, executive vice president for administration and finance.“Those offices always collaborate on helping solve problems for students, but being in the same facility will amp that up greatly.” The Center is named for Willard D. -

Fall 2009 Cover: Richard F

The FALL 2009 MercerianA PUBLICATION OF MERCER UNIVERSITY | WWW . MERCER . EDU Young Alumni Making a Difference Celebrate the Legends: Homecoming ’09 Revitalizing Macon’s Historic Neighborhoods Mercer Libraries: Changing Old Notions University Sets New Enrollment Record CONTENTS Departments 4 VIEWPOINT 5 ON THE QUAD 36 HEALTH SCIENCES UpDATE 42 BEARS ROUNDUP 48 CLAss NOTES 53 GIVING Features Young Mercerians 12 Making a Difference Five recent graduates are going places. Revitalizing Macon’s 22 First Neighborhoods College Hill Corridor accelerates Mercer’s investments. Mercer Libraries 31 Changing Old Notions This isn’t your grandfather’s (or grandmother’s) library. Celebrate the Legends: 40 Mercer Homecoming ’09 New fall tradition is bigger and better. HOTO P ON THE COVER: Mercer’s young alumni are making a difference in their professions DENDEN and their communities. Left to right: Rajesh Pandey, ’93; Mackenzie Eaglen, ’99; I Olu Menjay, ’95; Matt Trevathan, ’98; and Tom Abbott, ’04. OGER R 2 THE MERCERIAN | FALL 2009 COVER: RICHARD F. WILSON PHOTO OurLens InLate in the Village New eating establishments, across the street from the Macon campus, have become very popular among students, especially during the evening hours and on weekends. THE MERCERIAN | FALL 2009 3 A PUBLICATION OF MERCER UNIVERSITY Viewpoint TheMercerian VOLUME 19, NUMBER 2 FALL 2009 PRESIDENT William D. Underwood, J.D. CHANCELLOR R. Kirby Godsey, Th.D., Ph.D. Institutional Quality is PROVOST Wallace L. Daniel, Ph.D. EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT FOR Measured by Alumni ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE James S. Netherton, Ph.D. SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT FOR MARKETING Achievement COMMUNICATIONS AND CHIEF OF STAFF Larry D. -

ED 053 648 AUTHOR TITLE INSTITUTION PUB DATE AVAILABLE from EDRS PRICE DESCRIPTORS ABSTRACT DOCUMENT RESUME HE 002 380 Warga, Ri

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 053 648 HE 002 380 AUTHOR Warga, Richard G. TITLE Student Expense Budgets of American Colleges and Universities for the 1968-69 Academic Year. INSTITUTION Educational Testing Service, Princeton, N.J. PUB DATE Mar 68 NOTE 67p. ;College Scholarship Service Technical Reports AVAILABLE FROM Educational Testing Service, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 BC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Costs, *Educational Finance, *Fees, *Financial Needs, Higher Education, *Student Costs, Tuition ABSTRACT This annual booklet furnishes information on the costs of attending U.S. colleges and universities. Data on some Canadian and a number of community colleges are also included. The expenses reported cover a 2-term academic year. Each entry is divided into sections on: tuition and fees, resident budgets, commuting budgets, and out of state charges. An asterisk indicates whether the institution has a guaranteed tuition or fixed-loan plan. The publication is intended to: help financial air officers set appropriate schooling allowances as adjustments to entries made in the "Parents' Confidential Statements";' facilitate cooperation among institutions on awards to mutual aid candidates; and serve as a ready aid to scholarship sponsors. (JS) ID STUDENT EXPENSE BUDGETS RICHARD G. WARGA rNrs, OF AMERICAN COLLEGES Lr\ AND UNIVERSITIES FOR THE 1968-69 ACADEMIC YEAR CZ) college scholarship service technical reports a U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEHREPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OROPIN- IONS STATED DO NOTNECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY EDUCATIONAL TESTING SERVICE PRINCETON NEW JERSEY BERKELEY CALIFORNIA 4.-1.41410,-.Xik144. -

When the End Comes to Higher Education Institutions, 1890-2019: a Data Source Virginia Sapiro Boston University

When the End Comes to Higher Education Institutions, 1890-2019: A Data Source Virginia Sapiro Boston University This is a partial list of the concluding episodes of the independent existence of a selection of higher education institutions from 1890 to the beginning of 2019. It aims to include all institutions that were ever regionally accredited at the bachelors level or above or whose resources contributed in a genealogical sense to an institution that was accredited at that level. Or the era before accreditation it includes all institutions that were authorized to confer bachelors degrees or above or that contributed in a genealogical sense to an institution so authorized. It excludes straightforward transformations of an institution, as when an academy or normal school is re-chartered to become a college or university. It excludes for-profit institutions because their lives and deaths are very different given that they are treated as commodities with the primary purpose of revenue enhancement for owners. This listing shows different kinds of finality. These include: o The institution simply closes. In some cases the assets are acquired by another or successor institution of higher education, which may acknowledge the closed institution, for example, by naming a program after it, but the closed institution no longer has an independent existence. o One institution merges into another. Even if its name is preserved, for example, as the name of a college in a university, it no longer has separate accreditation or autonomy. o A new higher education institution is created by the merging of previously existing institutions. This list is arranged by year and then by alphabetical order of the latest state in which the institution or its successor existed. -

Fall 2002 • Volume 12, Number 2

THE MERCEA Publication for Alumni and Friends of Mercer University RIANFall 2002 • Volume 12, Number 2 Hatcher Leaves Footprints of Leadership By Judith Lunsford obert F. Hatcher, BB&T Georgia chairman, is all about School of Banking of the South. development districts. Each council At First National (renamed Trust has 30 to 40 people from the region leadership. He talks it, he walks it, and, fortunately, he Co. Bank and now known as who come together to discuss their SunTrust), Hatcher steadily moved up various business needs. generously provides it as a volunteer. the corporate ladder. In 1988, he was “The role of the Georgia Chamber senior vice president and senior credit is to represent the needs of business in During 2002, the Macon bank executive has filled three top officer at Trust Co. Bank of Middle the legislative session,” explained Georgia when First Liberty Financial Hatcher. “At these regional council Rleadership positions as chairman of Mercer University’s Board of Trustees, Corp. named him presi- meetings, the local mem- dent of Liberty Saving ‘Nothing seems bers are letting us know Macon’s Community Foundation and The Making of a Banker Georgia (UGA). He worked that sum- Bank’s Middle Georgia what they want the state impossible to Bob. the Georgia Chamber of Commerce. Born in Kewanee, Ill., he spent his mer in the mailroom of First National Division. Chamber to work on. It has While Hatcher admits holding several formative years there, where his father Bank (owned by Trust Company Bank) A year later, Hatcher He has a realistic been a very beneficial com- major leadership positions at the same owned a Coca-Cola bottling company.