Pit Viper Snakebite in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Snake Bite Protocol

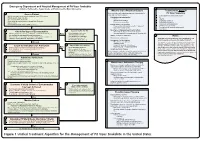

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Survey for the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus C. Catenatus) in the Carlyle Lake Region

Survey for the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus c. catenatus) in the Carlyle Lake Region: Final Report for Summer 2003 – Spring 2004 Submitted to the: Illinois Department of Natural Resources In Fulfillment of DNR Contract Number R041000001 19 January 2005 Submitted by: Christopher A. Phillips and Michael J. Dreslik Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity 607 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 INTRODUCTION At the time of European settlement, the eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) was found throughout the northern two-thirds of Illinois. There are accounts of early travelers and farmers encountering 20 or more massasaugas in a single season (Hay, 1893). As early as 1866, however, the massasauga was noted as declining (Atkinson and Netting, 1927). Through subsequent years, habitat destruction and outright persecution reduced the Illinois range of the massasauga to a few widely scattered populations. Of the 24 localities Smith (1961) listed, only five may remain extant (Phillips et al., 1999a) and abundance estimates at all but one are less than 50 individuals (Anton, 1999; Wilson and Mauger, 1999). The exception is the Carlyle Lake population, where recent size estimates have exceeded 100 individuals (Phillips et al.,1999b; Ibid 2001). A cooperative effort between Scott Ballard of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and site personnel at IDNR parks and Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) personnel at Carlyle Lake resulted in approximately 30 reports of the massasauga between 1991 and 1998 (S. Ballard, pers. com.). Most of these reports were associated with mowing and a few were the result of road mortality or incidental encounters with park personnel and visitors. -

COTTONMOUTH Agkistrodon Piscivorus

COTTONMOUTH Agkistrodon piscivorus Agkistrodon is derived from ankistron and odon which in Greek mean “fishhook” and “tooth or teeth;” referring to the curved fangs of this species. Piscivorus is derived from piscis and voro which in Latin mean “fish” and “to eat”. Another common name for cottonmouth is water moccasin. The Cottonmouth is venomous. While its bite is rarely fatal, tissue damage is likely to occur and can be severe if not treated promptly. IDENTIFICATION Appearance: The cottonmouth is a stout- bodied venomous snake that reaches lengths of 30 to 42 inches as adults. Most adults are uniformly dark brown, olive, or black, tending to lose the cross banded patterning with age. Some individuals may have a dark cheek stripe (upper right image). The cottonmouth has the diagnostic features of the pit-viper family such as a wedge-shaped head, sensory pits between the eyes and nostrils, and vertical “cat-like” pupils. Juveniles are lighter and more boldly patterned with a yellow coloration toward the tip of the tail (lower right image). Dorsal scales are weakly keeled, and the subcaudal scales form only one row. Cottonmouths also have a single anal Mike Redmer plate. Subspecies: There are three subspecies of the cottonmouth. The Western Cottonmouth (A. p. leucostoma) is the only subspecies found in the Midwest. The term leucostoma refers to the white interior of mouth. Confusing Species: The non-venomous watersnakes (Nerodia) are commonly confused with Cottonmouths across their range, simply because they are snakes in water. Thus it is important to note that Cottonmouths are only found in southernmost Midwest. -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis Radix, in Ohio

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 6-30-1945 The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix, in Ohio Roger Conant Zoological Society of Philadelphia Edward S. Thomas Ohio State Museum Robert L. Rausch University of Washington, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Conant, Roger; Thomas, Edward S.; and Rausch, Robert L., "The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix, in Ohio" (1945). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 378. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/378 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1945, NO.2 COPEIA June 30 The Plains Garter Snake, Thamnophis radix, in Ohio By ROGER CONANT, EDWARD S. THOMAS, and ROBERT L. RAUSCH HE announcement that Thamnophis radix, the plains garter snake, oc T curs in Ohio and is not rare in at least one county, will surprise most herpetologists and students of animal distribution. Since the publication of Ruthven's monograph on the genus (1908), almost all authors have followed his definition of the range of this species, giving eastern Illinois as its eastern most limit. Ruthven (po 80), however, believed that radix very probably would be found in western Indiana, a supposition since substantiated by Schmidt and Necker (1935: 72), who report the species from the dune region of Lake and Porter counties. -

Agkistrodon Piscivorus)

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2019 Behavioral Aspects Of Chemoreception In Juvenile Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon Piscivorus) Chelsea E. Martin Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Chelsea E., "Behavioral Aspects Of Chemoreception In Juvenile Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon Piscivorus)" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3466. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3466 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF CHEMORECEPTION IN JUVENILE COTTONMOUTHS (AGKISTRODON PISCIVORUS) A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Biology By Chelsea E. Martin December 2019 Copyright 2019 by Chelsea Elizabeth Martin ii BEHAVIORAL ASPECTS OF CHEMORECPTION IN JUVENILE COTTONMOUTHS (AGKISTRODON PISCIVORUS) Biology Missouri State University, December 2019 Master of Science Chelsea E. Martin ABSTRACT For snakes, chemical recognition of predators, prey, and conspecifics has important ecological consequences. -

Snake Bite Prevention What to Do If You Are Bitten

SNAKE BITE PREVENTION It has been estimated that 7,000–8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, and for around half a dozen people, these bites are fatal. In 2015, poison centers managed over 3,000 cases of snake and other reptile bites during the summer months alone. Approximately 80% of these poison center calls originated from hospitals and other health care facilities. Venomous snakes found in the U.S. include rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and coral snakes. They can be especially dangerous to outdoor workers or people spending more time outside during the warmer months of the year. Most snakebites occur when people accidentally step on or come across a snake, frightening it and causing it to bite defensively. However, by taking extra precaution in snake-prone environments, many of these bites are preventable by using the following snakebite prevention tips: Avoid surprise encounters with snakes: Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather. They also tend to hide in places where they are not readily visible, so stay away from tall grass, piles of leaves, rocks, and brush, and avoid climbing on rocks or piles of wood where a snake may be hiding. When moving through tall grass or weeds, poke at the ground in front of you with a long stick to scare away snakes. Watch where you step and where you sit when outdoors. Shine a flashlight on your path when walking outside at night. Wear protective clothing: Wear loose, long pants and high, thick leather or rubber boots when spending time in places where snakes may be hiding. -

Species Assessment for the Midget Faded Rattlesnake (Crotalus Viridis Concolor)

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR THE MIDGET FADED RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS CONCOLOR ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 AMBER TRAVSKY AND DR. GARY P. BEAUVAIS 1 Real West Natural Resource Consulting, 1116 Albin Street, Laramie, WY 82072; (307) 742-3506 2 Director, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, Dept. 3381, 1000 E. University Ave., Laramie, WY 82071; (307) 766-3023 prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming October 2004 Travsky and Beauvais – Crotalus viridus concolor October 2004 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 2 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 2 Morphological Description........................................................................................................... 3 Taxonomy and Distribution ......................................................................................................... 4 Habitat Requirements ................................................................................................................. 6 General ............................................................................................................................................6 Area Requirements..........................................................................................................................7 -

Pit Vipers: from Fang to Needle—Three Critical Concepts for Clinicians

Tuesday, July 28, 2021 Pit Vipers: From Fang to Needle—Three Critical Concepts for Clinicians Keith J. Boesen, PharmD & Nicholas B. Hurst, M.D., MS Disclosures / Potential Conflicts of Interest • Keith Boesen and Nicholas Hurst are employed by Rare Disease Therapeutics, Inc. (RDT) • RDT is a U.S. company working with Laboratorios Silanes, S.A. de C.V., a company in Mexico • Laboratorios Silanes manufactures a variety of antivenoms Note: This program may contain the mention of suppliers, brands, products, services or drugs presented in a case study or comparative format using evidence-based research. Such examples are intended for educational and informational purposes and should not be perceived as an endorsement of any particular supplier, brand, product, service or drug. 2 Learning Objectives At the end of this session, participants should be able to: 1. Describe the venom variability in North American Pit Vipers 2. Evaluate the clinical symptoms associated with a North American Pit Viper envenomation 3. Develop a treatment plan for a North American Pit Viper envenomation 3 Audience Poll Question: #1 of 5 My level of expertise in treating Pit Viper Envenomation is… a. I wouldn’t know where to begin! b. I have seen a few cases… c. I know a thing or two because I’ve seen a thing or two d. I frequently treat these patients e. When it comes to Pit Viper envenomation, I am a Ssssuper Sssskilled Ssssnakebite Sssspecialist!!! 4 PIT VIPER ENVENOMATIONS PIT VIPERS Loreal Pits Movable Fangs 1. Russel 1983 -Photo provided by the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center 1. -

Jennifer Szymanski Usfish and Wildlife Service Endangered

Written by: Jennifer Szymanski U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service Endangered Species Division 1 Federal Drive Fort Snelling, Minnesota 55111 Acknowledgements: Numerous State and Federal agency personnel and interested individuals provided information regarding Sistrurus c. catenatus’status. The following individuals graciously provided critical input and numerous reviews on portions of the manuscript: Richard Seigel, Robert Hay, Richard King, Bruce Kingsbury, Glen Johnson, John Legge, Michael Oldham, Kent Prior, Mary Rabe, Andy Shiels, Doug Wynn, and Jeff Davis. Mary Mitchell and Kim Mitchell provided graphic assistance. Cover photo provided by Bruce Kingsbury Table of Contents Taxonomy....................................................................................................................... 1 Physical Description....................................................................................................... 3 Distribution & State Status............................................................................................. 3 Illinois................................................................................................................. 5 Indiana................................................................................................................ 5 Iowa.................................................................................................................... 5 Michigan............................................................................................................ 6 Minnesota.......................................................................................................... -

Mating in Free-Ranging Neotropical Rattlesnakes, Crotalus Durissus: Is It Risky for Males?

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 225-227 (2021) (published online on 01 February 2021) Mating in free-ranging Neotropical rattlesnakes, Crotalus durissus: Is it risky for males? Selma Maria Almeida-Santos1,*, Thiago Santos2, and Luis Miguel Lobo1 Field observations of the mating behaviour of snakes The male remained stretched out for about 20 minutes are scarce, probably because of the secretive nature and and showed no defensive posture even with the presence low encounter rates of many species (Sasa and Curtis, of the observer. We then noticed drops of blood on the 2006). In the Neotropical rattlesnake, Crotalus durissus vegetation and the hemipenis (Fig. 1 E-F). We could not Linnaeus, 1758, mating has been reported only in determine the origin of the blood, but we suggest two captive individuals (Almeida-Santos et al., 1999). Here nonexclusive hypotheses. The hemipenis spicules may we describe the first record of the mating behaviour of have hurt the female’s vagina while she was dragging the the Neotropical rattlesnake, Crotalus durissus, in nature male over a long distance. Alternatively, the male may (Fig. 1 A). have suffered an injury to the hemipenis while being Observations were made on 9 March 2017, at 14:54 h, dragged quickly by the female. The slow hemipenis a warm and sunny day (temperature = 27.1 oC; relative retraction and the male’s fatigue after copulation may humidity = 66%), in an ecotone between dry forest and better support the second hypothesis. Cerrado (Brazilian savannah) in Prudente de Morais, Potential costs for male C. durissus during mating Minas Gerais, Brazil (-19.2841 °S,-44.0628 °W; datum season include increased activity and energy expenditure WGS 84).