State of the Panth, Report 6 September 2020 State of the Panth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Golden Temple

Golden Temple Golden Temple, Amritsar Golden Temple or Harmandir Sahib is the place of pilgrimage for Sikhs located in Amritsar. The temple was designed by Guru Arjun Dev, the fifth Sikh guru. There is no restriction for the member of any community or religion to visit the temple. This tutorial will let you know about the history of the temple along with the structures present inside. You will also get the information about the best time to visit it along with how to reach the temple. Audience This tutorial is designed for the people who would like to know about the history of Golden Temple along with the interiors and design of the temple. This temple is visited by many people from India and abroad. Prerequisites This is a brief tutorial designed only for informational purpose. There are no prerequisites as such. All that you should have is a keen interest to explore new places and experience their charm. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2017 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute, or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. -

Sikhism in the United States of America Gurinder Singh Mann

1 Sikhism in the United States of America Gurinder Singh Mann The history of the Sikhs is primarily associated with the Punjab, a region in northwest India they call their homeland (Grewal 1990). Situated among the dominant communities of the Hindus and Muslims, the Sikhs have, historically, remained a minority even within the Punjab. Beginning in the seventeenth century, groups of Sikh traders moved into other parts of the subcontinent and established small communities in far-off cities; the number and size of these communities outside the Punjab remained rather small. The annexation of the Punjab by the British in 1849 opened doors for the Sikhs to migrate to distant countries as members of the imperial working force. In the closing years of the nineteenth century, we see the emergence of small but distinct Sikh communities in East Africa and Southeast Asia (Barrier and Dusenbery 1989). At the turn of the twentieth century, the Sikhs expanded their range of travel further and began to arrive in North America. They constituted a large majority of what Raymond Williams in his introduction to this section calls "a thriving farming community in California." Despite great personal and legal hardships in the mid-twentieth century, the Sikhs persisted in their efforts to settle in the new land and today, they constitute a vibrant community of over 200,000 spread throughout the United States, with distinct concentrations in California, Chicago, Michigan, and the greater New York and Washington D. C. areas. La Brack (1988) made a pioneering study of the history of the Sikhs in the United States. -

Siri Guru Singh Sabha Croydon

SIRI GURU SINGH SABHA CROYDON 176 St. James’s Road, Croydon, Surrey. CR0 2BU Telephone No 020 8688 8155 Registered Charity Number 282163 Guroo Pyaree Saadh Sangat Jeo, Vaheguroo Ji Ka Khalsa, Vaheguroo Ji Ki Fateh, Rules for Anand Karaj Bookings: 1. Gurdwara is unable to arrange catering for weddings, were, as Gurdwara Kitchen will available for the Private Catering arrangements. 2. During the wedding ceremony, in front of the Guru Granth Sahib, NO KALGI or SEHRA should be tied or hanging upon the top of the turban. After the wedding ceremony, NO FLOWER PETALS, GARLANDS,ETC . For the wedded couple is to be present in front of Guru Granth Sahib Ji. No “ SEHRA ” or “ SIKHYA ” by any member of any Ragi etc. Only 5 members from each family of the Boys Side & Girls Side may sit next to the wedded couple during the ceremony (Phere).No person is allowed to stand around the Guru Granth Sahib Ji when the Phere shake place. As all the above is not guided in Maryada of Anand Karaj 3. Only Vegetarian (No egg, No fish) Catering is allowed on premises 4. The Intention to Marry Letter regarding the wedding issued by the Town Hall should be handed over to the marriage registrars or general secretary as soon as it is received or latest 3 weeks prior to the wedding ceremony. 5. NO REGISTER WEDDING CEREMONY WILL TAKE PLACE UNTIL THE WEDDING LETTER HAS BEEN ISSUED BY THE TOWN HALL 6. Both the family has to complie with the above rules. According Sikh Rehit Maryada Anand Sanskar should follow these rules Article XVIII-Anand Sanskar (Lit. -

Know Your Heritage Introductory Essays on Primary Sources of Sikhism

KNOW YOUR HERIGAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES , C HANDIGARH KNOW YOUR HERITAGE INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS ON PRIMARY SOURCES OF SIKHISM Dr Dharam Singh Prof Kulwant Singh INSTITUTE OF S IKH S TUDIES CHANDIGARH Know Your Heritage – Introductory Essays on Primary Sikh Sources by Prof Dharam Singh & Prof Kulwant Singh ISBN: 81-85815-39-9 All rights are reserved First Edition: 2017 Copies: 1100 Price: Rs. 400/- Published by Institute of Sikh Studies Gurdwara Singh Sabha, Kanthala, Indl Area Phase II Chandigarh -160 002 (India). Printed at Adarsh Publication, Sector 92, Mohali Contents Foreword – Dr Kirpal Singh 7 Introduction 9 Sri Guru Granth Sahib – Dr Dharam Singh 33 Vars and Kabit Swiyyas of Bhai Gurdas – Prof Kulwant Singh 72 Janamsakhis Literature – Prof Kulwant Singh 109 Sri Gur Sobha – Prof Kulwant Singh 138 Gurbilas Literature – Dr Dharam Singh 173 Bansavalinama Dasan Patshahian Ka – Dr Dharam Singh 209 Mehma Prakash – Dr Dharam Singh 233 Sri Gur Panth Parkash – Prof Kulwant Singh 257 Sri Gur Partap Suraj Granth – Prof Kulwant Singh 288 Rehatnamas – Dr Dharam Singh 305 Know your Heritage 6 Know your Heritage FOREWORD Despite the widespread sweep of globalization making the entire world a global village, its different constituent countries and nations continue to retain, follow and promote their respective religious, cultural and civilizational heritage. Each one of them endeavours to preserve their distinctive identity and take pains to imbibe and inculcate its religio- cultural attributes in their younger generations, so that they continue to remain firmly attached to their roots even while assimilating the modern technology’s influence and peripheral lifestyle mannerisms of the new age. -

Sikhism Mini Book Pre-K, Kindergarten, & 1St Grade

Sikhism Mini Book Pre-K, Kindergarten, & 1st Grade By: Starlight Treasures Sikhism Khanda Turban Kanga Kara Gurdwara Copyright Starlight Treasures Kirpan My book all about Name:_______________________________________________________ Copyright Starlight Treasures My book all about Name:_______________________________________________________ Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism is the belief in one god. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism is the belief in one god. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism is the youngest of the world’s five biggest religions. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism is the youngest of the world’s five biggest religions. Copyright Starlight Treasures People who believe in Sikhism are called Sikhs. Copyright Starlight Treasures People who believe in Sikhism are called Sikhs. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism originated in India around 500 years ago. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism originated in India around 500 years ago. Copyright Starlight Treasures Color the land green and the water blue. Arabian Bay of Sea Bengal Copyright Starlight Treasures Color the land green and the water blue. Arabian Bay of Sea Bengal Copyright Starlight Treasures The Flag of India The flag is orange, white and green. Copyright Starlight Treasures The Flag of India The flag is orange, white and green. Copyright Starlight Treasures They speak Hindi. Namaste Hello Alavida Goodbye Dhanyavaad Thank You Copyright Starlight Treasures They speak Hindi. Namaste Hello Alavida Goodbye Dhanyavaad Thank You Copyright Starlight Treasures The founder of Sikhism is Guru Nanak. Copyright Starlight Treasures The founder of Sikhism is Guru Nanak. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism teaches that all humans are created equally. Copyright Starlight Treasures Sikhism teaches that all humans are created equally. Copyright Starlight Treasures The symbol of Sikhism is called the Khanda. -

Dasvandh Network

Dasvandh To selflessly give time, resources, and money to support Panthic projects www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Building a Nation The Role of Dasvandh in the Formation of a Sikh culture and space Above: A painting depicting Darbar Sahib under construction, overlooked by Guru Arjan Sahib. www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Guru Nanak Sahib Ji Guru Nanak Sahib’s first lesson was an act of Dasvandh: when he taught us the true bargain: Sacha Sauda www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork 3 Golden Rules The basis for Dasvandh are Guru Nanak Sahib’s key principles, which he put into practice in his own life Above: Guru Nanak Sahib working in his fields Left: Guru Nanak Sahib doing Langar seva www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Mata Khivi & Guru Angad Sahib Guru Angad Sahib ji and his wife, the greatly respected Mata Khivi, formalized the langar institution. In order to support this growing Panthic initiative, support from the Sangat was required. www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Community Building Guru Amar Das Sahib started construction on the Baoli Sahib at Goindval Sahib.This massive construction project brought together the Sikhs from across South Asia and was the first of many institution- building projects in the community. www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Guru RamDas Sahib Ji Besides creating the sarovar at Amritsar, Guru RamDas Sahib Ji designed and built the entire city of Amritsar www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Guru Arjan Sahib & Dasvandh It was the monumental task of building of Harmandir Sahib that allowed for the creation of the Dasvandh system by Guru Arjan Sahib ji. -

The Sikh Prayer)

Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to: Professor Emeritus Dr. Darshan Singh and Prof Parkash Kaur (Chandigarh), S. Gurvinder Singh Shampura (member S.G.P.C.), Mrs Panninder Kaur Sandhu (nee Pammy Sidhu), Dr Gurnam Singh (p.U. Patiala), S. Bhag Singh Ankhi (Chief Khalsa Diwan, Amritsar), Dr. Gurbachan Singh Bachan, Jathedar Principal Dalbir Singh Sattowal (Ghuman), S. Dilbir Singh and S. Awtar Singh (Sikh Forum, Kolkata), S. Ravinder Singh Khalsa Mohali, Jathedar Jasbinder Singh Dubai (Bhai Lalo Foundation), S. Hardarshan Singh Mejie (H.S.Mejie), S. Jaswant Singh Mann (Former President AISSF), S. Gurinderpal Singh Dhanaula (Miri-Piri Da! & Amritsar Akali Dal), S. Satnam Singh Paonta Sahib and Sarbjit Singh Ghuman (Dal Khalsa), S. Amllljit Singh Dhawan, Dr Kulwinder Singh Bajwa (p.U. Patiala), Khoji Kafir (Canada), Jathedar Amllljit Singh Chandi (Uttrancbal), Jathedar Kamaljit Singh Kundal (Sikh missionary), Jathedar Pritam Singh Matwani (Sikh missionary), Dr Amllljit Kaur Ibben Kalan, Ms Jagmohan Kaur Bassi Pathanan, Ms Gurdeep Kaur Deepi, Ms. Sarbjit Kaur. S. Surjeet Singh Chhadauri (Belgium), S Kulwinder Singh (Spain), S, Nachhatar Singh Bains (Norway), S Bhupinder Singh (Holland), S. Jageer Singh Hamdard (Birmingham), Mrs Balwinder Kaur Chahal (Sourball), S. Gurinder Singh Sacha, S.Arvinder Singh Khalsa and S. Inder Singh Jammu Mayor (ali from south-east London), S.Tejinder Singh Hounslow, S Ravinder Singh Kundra (BBC), S Jameet Singh, S Jawinder Singh, Satchit Singh, Jasbir Singh Ikkolaha and Mohinder Singh (all from Bristol), Pritam Singh 'Lala' Hounslow (all from England). Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon, S. Joginder Singh (Winnipeg, Canada), S. Balkaran Singh, S. Raghbir Singh Samagh, S. Manjit Singh Mangat, S. -

Simran Healing

AAA SSSpppiiirrriiitttuuuaaalll MMMiiinnnddd------BBBooodddyyy HHHeeeaaallliiinnnggg MMMeeettthhhoooddd ooofff UUUsssiiinnnggg PPPooowwweeerrr ooofff CCCooonnnsssccciiiooouuusssnnneeessssss tttooo HHHeeeaaalll AAAsss eeexxxppplllaaaiiinnneeeddd iiinnn SSSiiirrriii GGuuurrruuu GGGrrraaannnttthhh SSSaaahhhiiibbbjjjiii by GGGuuurrrmmmiiittt SSSiiinnnggghhh First Edition www.naamaukhad.blogspot.com © Author This book has been distributed free for personal use. No part of this book is to be printed for sale or distribution. 1 TTTaaabbbllleee ooofff CCCooonnnttteeennntttsss Introduction 1. Origin of Simran Healing 2. The disease – why me? 3. Healing the Mind, Heals the Body 4. Understanding 1: We are Jyot Swaroop (divine nature) 5. Understanding 2: The World is a creation of consciousness. (Oneness) 6. Understanding 3: The nature of the created World is a mind pattern. 7. Understanding 4: As are your thoughts so is your state of mind and accordingly are events/circumstances in your life. 8. SIMRAN METHOD 9. Naam 10. Simran Healing Method 2 IIINNNTTTRRROOODDDUUUCCCTTTIIIOOONNN We choose our own healing path. Many choose the prevailing medical system and handover responsibility to heal their physical body to others. Some know that they are more than just a physical body to be treated in parts through mechanical and chemical means. These people refuse to remain on medication for rest of their lives. They also refuse to accept removal of “offending” organ. These people are the one who take to other healing methods collectively termed as Alternative Medical Systems. Some go even further and empower themselves to self-heal. Simran healing is spiritual path to such an empowerment. Simran healing is a method which places your conscious awareness at a level that empowers you to direct the creative power of consciousness to self-heal. -

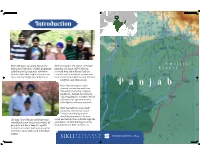

Introduction

Introduction 2YHU\HDUVDJR*XUX1DQDNWKH 6LNKLHPHUJHGLQWKHUHJLRQRI3DQMDE ILUVW*XUX3HUIHFWLRQRI6LNKL SRSXODUO\ OLWHUDOO\WKH/DQGRI)LYH5LYHUV FDOOHG6LNKLVP LQVSLUHGDUHYROXWLRQ LQ6RXWK$VLD*XUX1DQDNODLGWKH LQ6RXWK$VLDWKDWVRXJKWWRWUDQVIRUP IRXQGDWLRQVIRUDGLVWLQFWXQLTXHDQG WKHVRFLDODQGUHOLJLRXVFRQGLWLRQVRI PRQRWKHLVWLFIDLWKZLWKLWVRZQIRXQGHU VFULSWXUHDQGHWKLFDOFRGH *XUX1DQDNXQHTXLYRFDOO\ UHMHFWHGH[FOXVLYLVPDQGFDVWH KLHUDUFK\RIH[LVWLQJUHOLJLRXV WUDGLWLRQV,QVWHDGKHFUHDWHGD KLJKO\HJDOLWDULDQVRFLHW\LQZKLFK DOOKXPDQEHLQJVZHUHWUHDWHG ZLWKGLJQLW\DQGVHHQDVHTXDOV 2YHUWKHQH[WWZRDQGDKDOI FHQWXULHVQLQH*XUXVZRXOG IROORZFRQWULEXWLQJWRWKLV UHYROXWLRQDU\YLVLRQRIDQHZ WKHWLPH*XUX1DQDNHQYLVLRQHGDQG VRFLDODQGLQWHOOHFWXDORUGHUWKURXJKWKH HVWDEOLVKHGDQHZVRFLDORUGHUZKHUHDOO DUWLFXODWLRQRI6LNKWKHRORJ\DQGWKH SHRSOHZRXOGIHHODGHHSWKRXJKWIXO HVWDEOLVKPHQWRI6LNKLQVWLWXWLRQV FRQQHFWLRQWRWKHLUIDLWKDQGZRXOGEH HQWLWOHGWRHTXDOULJKWVDQGLQGLYLGXDO UHVSHFW Sikh Heritage Month Posters.indd 3 5/21/2014 10:03:14 PM *XUX1DQDN &ROXPEXVODQGVLQWKH$PHULFDV ŧ Gurus /HRQDUGRGD9LQFLSDLQWVWKH0RQD/LVD 0LFKDHODQJHORSDLQWVFHLOLQJRIWKH6LVWLQH&KDSHO *XUX$QJDG ŭ*XUXŮLVGHULYHGIURPguŧGDUNQHVV RI6LNKVSLULWXDODXWKRULW\7KH*XUX ŧ 0DUWLQ/XWKHUSRVWVKLV7KHVHV DQGruŧOLJKW7KXVIRU6LNKVDJXUXLVD *UDQWK6DKLEZDVGHFODUHGWREHWKH*XUX VLQJXODULQVWLWXWLRQJXLGLQJWKHVHHNHU IRUHYHUE\*XUX*RELQG6LQJKLQ IURPLJQRUDQFHWRHQOLJKWHQPHQW7KH *XUX$PDUGDV *XUXLV3HUIHFWLRQIRUD6LNK $OWKRXJKWKHUHZHUHQRORQJHU (OL]DEHWK,LVFURZQHG4XHHQRI(QJODQG ŧ KXPDQ*XUXVWKHG\QDPLFZLVGRP *DOLOHR*DOLOHL :LOOLDP6KDNHVSHDUHDUHERUQ 6LNKVEHOLHYHWKDWWKHVDPHGLYLQHOLJKW -

Heartoflove.Pdf

Contents Intro............................................................................................................................................................. 18 Indian Mystics ............................................................................................................................................. 20 Brahmanand ............................................................................................................................................ 20 Palace in the sky .................................................................................................................................. 22 The Miracle ......................................................................................................................................... 23 Your Creation ...................................................................................................................................... 25 Prepare Yourself .................................................................................................................................. 27 Kabir ........................................................................................................................................................ 29 Thirsty Fish .......................................................................................................................................... 30 Oh, Companion, That Abode Is Unmatched ....................................................................................... 31 Are you looking -

Harpreet Singh

FROM GURU NANAK TO NEW ZEALAND: Mobility in the Sikh Tradition and the History of the Sikh Community in New Zealand to 1947 Harpreet Singh A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, The University of Otago, 2016. Abstract Currently the research on Sikhs in New Zealand has been defined by W. H. McLeod’s Punjabis in New Zealand (published in the 1980s). The studies in this book revealed Sikh history in New Zealand through the lens of oral history by focussing on the memory of the original settlers and their descendants. However, the advancement of technology has facilitated access to digitised historical documents including newspapers and archives. This dissertation uses these extensive databases of digitised material (combined with non-digital sources) to recover an extensive, if fragmentary, history of South Asians and Sikhs in New Zealand. This dissertation seeks to reconstruct mobility within Sikhism by analysing migration to New Zealand against the backdrop of the early period of Sikh history. Covering the period of the Sikh Gurus, the eighteenth century, the period of the Sikh Kingdom and the colonial era, the research establishes a pattern of mobility leading to migration to New Zealand. The pattern is established by utilising evidence from various aspects of the Sikh faith including Sikh institutions, scripture, literature, and other historical sources of each period to show how mobility was indigenous to the Sikh tradition. It also explores the relationship of Sikhs with the British, which was integral to the absorption of Sikhs into the Empire and continuity of mobile traditions that ultimately led them to New Zealand. -

BRITISH SIKH REPORT 2017 an INSIGHT INTO the BRITISH SIKH COMMUNITY British Sikh Report 2017

BRITISH SIKH REPORT 2017 AN INSIGHT INTO THE BRITISH SIKH COMMUNITY British Sikh Report 2017 The British Sikh Report (BSR) has been published annually since 2013. It is based on a survey of Sikhs living in the UK, gathering information about views on their faith, and on topical British issues – political, economic, social and cultural. British Sikh Report website: www.britishsikhreport.org PREVIOUS REPORTS: Published March 2017 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 ARTICLE: SIKH DHARAM – GENDER EQUALITY, CULTURAL CHANGE 5 AND ‘BREAKING GLASS CEILINGS’. BRITISH SIKH REPORT 2017: SURVEY INTRODUCTION 12 BSR 2017: DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE SURVEY 13 IDENTITY AND ETHNICITY 16 SIKHI AND OBSERVANCE OF FIVE KAKAARS 20 QUALIFICATIONS AND EMPLOYMENT 24 EUROPEAN UNION 27 EU REFERENDUM EFFECT OF BREXIT HATE CRIMES INDIA AND PUNJAB ISSUES 30 LINKS WITH PUNJAB ATTITUDES TOWARDS 1947 PARTITION OF INDIA AND PUNJAB ATTITUDES TOWARDS AN INDEPENDENT SIKH STATE LIFE AS SIKHS IN BRITAIN 34 VOLUNTEERING GURDWARA MANAGEMENT ISSUES MAIN ISSUES AFFECTING SIKH WOMEN IN BRITAIN ANAND KARAJ CEREMONY SIKHS AND THE ARMED FORCES 40 JOINING THE ARMED FORCES NATIONAL SIKH MONUMENT HERITAGE AND CULTURE 41 PUNJABI, GURMUKHI AND THE BBC PUBLICATION OF SIKH AND PUNJABI HERITAGE MATERIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 42 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Welcome to the British Sikh Report 2017. This is the fifth in our series of strategic documents created by Sikhs about Sikhs, and for everyone with an interest in the lives of Sikhs in Britain. Over the last five years, we have developed robust and unrivalled statistical information about Sikhs living in Brit- ain. This highly influential annual document has been quoted by MPs and Peers, referred to in several pieces of research and white papers regarding faith in modern society, and used by a multitude of public authorities and private companies in identifying the needs of British Sikhs.