Evaluation of FAO Activities in Tajikistan. Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aga Khan Agency for Habitat Provides Refresher Courses for Certs

Enhancing readiness of emergency response volunteers in Tajikistan Aga Khan Agency for Habitat provides refresher courses for CERTs Rasht, Tajikistan, 23 April 2020 – The Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH) Tajikistan, through the financial support of the Government of Switzerland, completed refresher trainings for the Community Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) formed in Rasht valley. The trainings, which were conducted within the Integrated Health and Habitat Improvement (IHHI) project, are designed to enhance the readiness of the CERTs to respond to emergency situations across the Districts of Republican Subordination. The training prepares the volunteers to be the first responders in the event of a disaster. It capitalises on their knowledge of the terrain, language and culture, as captured by trainer Munira Qurbonmamadova, “Our approach is tailored to the cultural dynamics in each area. For example, in Shashvolon, we held a separate training for the women, which was very well received.” Shukrona, a local nurse and committed community volunteer who helped mobilise her fellow women volunteers agrees, “The training offered a safe place to learn freely and to practice. Women constitute a significant number of our communities so it’s important that their specific needs are considered in emergency response.” The trainings were undertaken in seven villages of Rasht, Roghun, Lakhsh, Tojikobod, Fayzobod, Nurobod, and Sangvor districts from 17 to 20 April. A total of 210 participants (equal representation of men and women) successfully concluded the two-day training, acquiring renewed theoretical knowledge and practical experience on first aid, Incident Command System (ICS), and search and rescue. They also enhanced techniques in bleeding prevention, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and victim transportation. -

Land Und Leute 22

Vorwort 11 Herausragende Sehenswürdigkeiten 12 Das Wichtigste in Kurze 14 Entfernungstabelle 20 Zeichenlegende 20 LAND UND LEUTE 22 Tadschikistan im Überblick 24 Landschaft und Natur 25 Gewässer und Gletscher 27 Klima und Reisezeit 28 Flora 29 Fauna 32 Umweltprobleme 37 Geschichte 42 Die Anfänge 42 Vom griechisch-baktrischen Reich bis zur Kushan-Dynastie 47 Eroberung durch die Araber und das Somonidenreich 49 Türken, Mongolen und das Emirat von Buchara 49 Russischer Einfluss und >Great Game< 50 Sowjetische Zeit 50 Unabhängigkeit und Burgerkrieg 52 Endlich Frieden 53 Tadschikistan im 21. Jahrhundert 57 Regierung 57 Wirtschaftslage 58 Kritik und Opposition 58 Tourismus 60 Politisches System in Theorie und Praxis 61 Administrative Gliederung 63 Wirtschaft 65 Bevölkerung und Kultur 69 Religionen und Minderheiten 71 Städtebau und Architektur 74 Volkskunst 77 Sprache 79 Literatur 80 Musik 85 Brauche 89 http://d-nb.info/1071383132 Feste 91 Heilige Statten 94 Die tadschikische Küche 95 ZENTRALTADSCHIKISTAN 102 Duschanbe 104 Geschichte 104 Spaziergang am Rudaki-Prospekt 110 Markt und Mahalla 114 Parks am Varzob-Fluss 115 Museen 119 Denkmaler 122 Duschanbe live 128 Duschanbe-Informationen 131 Die Umgebung von Duschanbe 145 Festung Hisor 145 Varzob-Schlucht 148 Romit-Tal 152 Tal des Karatog 153 Wasserkraftwerk Norak 154 Das Rasht-Tal 156 Ob-i Garm 158 Gharm 159 Jirgatol 159 Reiseveranstalter in Zentral tadschikistan 161 DER PAMIR 162 Das Dach der Welt 164 Ein geografisches Kurzportrait 167 Die Bewohner des Pamirs 170 Sprache und Religion 186 Reisen -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Tajikistan, Dushanbe–Kyrgyz Border Road Rehabilitation Project

Completion Report Project Number: 34569 Loan Number: 2062-TAJ August 2010 Tajikistan: Dushanbe–Kyrgyz Border Road Rehabilitation Project (Phase 1) CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – Tajik somoni (TJS) At Appraisal At Project Completion 15 November 2003 31 December 2009 TJS1.00 = $0.3274 $0.22988 $1.00 = TJS3.0544 TJS4.3500 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CAREC – Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation EIRR – economic internal rate of return GDP – gross domestic product ICB – international competitive bidding M&E – monitoring and evaluation MOTC – Ministry of Transport and Communication NCB – national competitive bidding OFID – OPEC Fund for International Development OPEC – Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries PIU – project implementation unit PRC – People’s Republic of China TA – technical assistance VOC – vehicle operating cost NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the government ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice-President X. Zhao, Operations 1 Director General J. Miranda, Central and West Asia Department (CWRD) Director H. Wang, Transport and Communications Division, CWRD Team leader F. Nuriddinov, Project Implementation Officer, CWRD Team members L. Chernova, Assistant Project Analyst, CWRD N. Kvanchiany, Senior Project Assistant, CWRD In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CONTENTS Page BASIC DATA MAP OF PROJECT LOCATION I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. EVALUATION OF DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION 2 A. Relevance of Design and Formulation 2 B. -

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

Swiss-Tajik Cooperation: Nearly 20 Years of Primary Healthcare Development

Swiss-Tajik Cooperation: Nearly 20 years of Primary Healthcare Development Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Population of the Republic of Tajikistan Swiss-Tajik Collaboration: Nearly 20 years of Primary Healthcare Development With high levels of poverty and two thirds of its nurses. This was achieved by putting greater people living in rural areas, Tajikistan’s primary focus on practical, clinical skills, communica- health care system and the quality education of tion techniques and providing early exposure its health workers are essential to make health to rural practice realities, with students working care more accessible. The Enhancing Primary directly with patients under the guidance of ex- Health Care Services Project (Project Sino) and perienced colleagues – as is routinely done in the Medical Education Reform Project (MEP) Switzerland. have been committed to the pursuit of Univer- To achieve the health-related Sustaina- sal Health Coverage (UHC) through develop- ble Development Goals, Switzerland promotes ment of the health system and medical educa- UHC through activities that establish social pro- tion reform for close to 20 years. The projects tection mechanisms in health and advocate for are supported by the Swiss Agency for De- access to quality healthcare. SDC in particular velopment and Cooperation (SDC) and imple- supports the drive towards UHC and that atten- Swiss-Tajik Cooperation: mented by the Swiss Tropical and Public Health tion is paid to the needs of the poor, such as the Nearly 20 years of Primary Institute (Swiss TPH). assistance provided in Tajikistan. Healthcare Development The projects were conceived to sup- port, and work directly with, the Ministry of Russia Health and Social Protection (MoHSP), the Re- p. -

The World Bank the STATE STATISTICAL COMMITTEE of the REPUBLIC of TAJIKISTAN Foreword

The World Bank THE STATE STATISTICAL COMMITTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN Foreword This atlas is the culmination of a significant effort to deliver a snapshot of the socio-economic situation in Tajikistan at the time of the 2000 Census. The atlas arose out of a need to gain a better understanding among Government Agencies and NGOs about the spatial distribution of poverty, through its many indicators, and also to provide this information at a lower level of geographical disaggregation than was previously available, that is, the Jamoat. Poverty is multi-dimensional and as such the atlas includes information on a range of different indicators of the well- being of the population, including education, health, economic activity and the environment. A unique feature of the atlas is the inclusion of estimates of material poverty at the Jamoat level. The derivation of these estimates involves combining the detailed information on household expenditures available from the 2003 Tajikistan Living Standards Survey and the national coverage of the 2000 Census using statistical modelling. This is the first time that this complex statistical methodology has been applied in Central Asia and Tajikistan is proud to be at the forefront of such innovation. It is hoped that the atlas will be of use to all those interested in poverty reduction and improving the lives of the Tajik population. Professor Shabozov Mirgand Chairman Tajikistan State Statistical Committee Project Overview The Socio-economic Atlas, including a poverty map for the country, is part of the on-going Poverty Dialogue Program of the World Bank in collaboration with the Government of Tajikistan. -

Tajikistan: Access to Resources for Human Development

Empovered lives. Resilient nations. N A T I O N A L H U M A N D E V E L O P M E N T R E P O R T 2 0 1 4 Tajikistan: access to resources for human development DUSHANBE - 2015 International Labour Organization The United Nations Population Fund The International Labour Organization (UNFPA) is an international institution (ILO) is a UN specialized agency which on development issues and delivering seeks the promotion of social justice a world where every pregnancy is wanted, and internationally recognized human every childbirth is safe and every young and labour rights. person’s potential is fulfilled. The report has been prepared in collaboration with a group of local consultants. The contents of this publication are not copyrighted. They may be reproduced partially or fully without the prior consent of UNDP or the Republic of Tajikistan. However, the report authors will appreciate if reference is made to this publication The views and opinions expressed in this report belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of UNDP, UNFPA and ILO. Dear reader, You are welcome to the latest National Human Development Report called Tajikistan: Access to Human Development prepared with the support of the UN Development Program and in close cooperation with the government, civil society and international organizations in Tajikistan. It is remarkable that this Report is presented during the final year of the National Development Strategy of the Republic of Tajikistan for the period of 2015, which was elaborated in consideration of the Millennium Development Goals for 2015 as well as the Living Standards Improvement Strategy of Tajikistan for 2013-2015. -

Tourism in Tajikistan As Seen by Tour Operators Acknowledgments

Tourism in as Seen by Tour Operators Public Disclosure Authorized Tajikistan Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER CONTENTS This work is a product of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS......................................................................i The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other INTRODUCTION....................................................................................2 information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. TOURISM TRENDS IN TAJIKISTAN............................................................5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS TOURISM SERVICES IN TAJIKISTAN.......................................................27 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank TOURISM IN KHATLON REGION AND 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: +1 (202) 522-2422; email: [email protected]. GORNO-BADAKHSHAN AUTONOMOUS OBLAST (GBAO)...................45 The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and li- censes, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, PROFILE AND LIST OF RESPONDENTS................................................57 Cover page images: 1. Hulbuk Fortress, near Kulob, Khatlon Region 2. Tajik girl holding symbol of Navruz Holiday 3. -

White Gold Or Women's Grief the Gendered Cotton

‘White Gold’ or Women’s Grief? The Gendered Cotton of Tajikistan – Oxfam GB October 2005 I. xecutive ummary 1 E S kept in the dark concerning their labour rights Contrary to dominant institutional and land rights; rural communities are not belief, cotton in Tajikistan, especially given its given any details about the extend of the farm present production structure, is not a cotton debt (estimated on a whole to have ‘strategic’ commodity; is highly inequitable in surpassed US$280 million by July 2005); for its distribution of financial gains in favour of nearly all female cotton workers, major investors rather than the majority-female farm incentives to work is the opportunity to collect workers; exploits the well-being and labour the meagre cotton picking earnings (about rights of children and rural households; leads US$0.03/kg) and the reward of collecting the ghuzapoya to rampant indebtedness of farms; induces end-of-season dried cotton stalks ( ) food insecurity, hunger, and poverty; is used as fuel, bartered or sold; the conditions socially destructive, causing widespread of many farms and farm workers is not unlike migration and dislocation of families; damages ‘bonded labour’ and ‘financial servitude’; not the micro and macro environments, cotton is thus a strategic commodity for contradicting principles of sustainable Tajikistan nor is it a ‘cash crop’ for rural economic development; and if not mitigated women and their households, with the crop of will likely lead to social and economic choice for the far majority being food crops aggravations. such as wheat, corn, potatoes and vegetables. A rapid qualitative study was con- The following advocacy and program- ducted during a three week period in March ming recommendations are presented to and April 2005 in the southern Khatlon Oxfam GB on the issue of gender and cotton province of Tajikistan and the capital city, production in Tajikistan. -

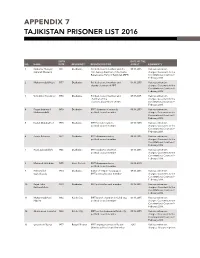

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges.