An Agenda for Reduction and Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Report (PDF)

FEMISE RESEARCH PROGRAMME A Perspective on the Future Dollar-Euro Exchange Rate: Implications for the Peripheral Mediterranean Countries Simon Neaime Institute of Money and Banking American University of Beirut September 2000 This text has been drafted with financial assistance from the Commission of the European Communities. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and therefore in no way reflect the offical opinion of the Commission A Perspective on the Future Dollar-Euro Exchange Rate: Implications for the Peripheral Mediterranean Countries* Project Coordinator: Simon Neaime Institute of Money and Banking American University of Beirut Email: [email protected] _________________________ *This work has benefited from a financial grant from the Commission of the European Communities within the context of the FEMISE program. The views expressed are those of the beneficiary and therefore in no way reflect the official opinion of the Commission. ABSTRACT There has been considerable interest in recent years in the prospective dollar- euro exchange rate motivated by the launch of the single currency in Europe. This project studies some of the factors that may constitute the main determinants of the dollar-euro exchange rate. In particular, it argues that in the year 2002−when the euro becomes legal tender within the euro area−there will be an appreciation in the value of the euro against the US dollar arising from shifts in demand towards the euro. Such shifts would work through EU trade invoicing, private portfolio diversification inside and outside the euro area, and central banks’ reserves diversification, strengthening the value of the euro against the dollar. -

List of Commercial Banks Maintaining Clearing Accounts with the ECCB

report and statement of accounts for the financial year ended 31 march 2020 i Letter of Transmittal 1 Monetary Stability ii Mission and Vision Statements 4 Financial Sector Stability ii Core Values 13 Fiscal and Debt Sustainability iii Monetary Council 17 Growth, Competitiveness and Employment Table of Contents iv Board of Directors 21 Organisational Effectiveness v Organisational Chart 33 Financial Results vi Management Structure 37 Corporate Governance Framework viii Agency Offices 46 Areas of Focus for 2020-2021 ix Highlights of the Year 53 List of Commercial Banks Maintaining Clearing Accounts with the ECCB xi Governor’s Foreword 54 Independent Auditors’ Report and Financial Statements EASTERNEastern CARIBBEANCaribbean CENTRALCentral BANK Bank 19 June 2020 Sirs In accordance with Article 48(1) of the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank Agreement 1983, I have the honour to transmit herewith the Bank’s Annual Report and Statement of Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2020, duly certified by the External Auditors. I am, Letter of Your Obedient Servant Transmittal Timothy N. J. Antoine GOVERNOR The Honourable Victor F Banks The Honourable Joseph E. Farrell Premier Premier ANGUILLA MONTSERRAT The Honourable Gaston Browne Dr The Honourable Timothy Harris Prime Minister Prime Minister ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA ST CHRISTOPHER (ST KITTS) AND NEVIS The Honourable Roosevelt Skerrit The Honourable Allen Chastanet Prime Minister Prime Minister COMMONWEALTH OF DOMINICA SAINT LUCIA eDr Th Right Honourable Keith Mitchell The Honourable Camillo Gonsalves Prime Minister Minister for Finance GRENADA SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES Tel: (869) 465-2537 • Fax: (869) 465-9562/1051 E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.eccb-centralbank.org SWIFT: ECCBKN I | EASTERN CARIBBEAN CENTRAL BANK ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Advancing the good of the people of the currency mission union by maintainng monetary and financial stability and Statement promoting growth and development. -

St Lucia 44 St Vincent and the Grenadines 47 Suriname 50 Trinidad and Tobago 52

~ . ' ,....•..•.•.........•....../. , . /": , .. ' ..""", .. " ," , "0" : .... ~ '" .. ~. • .' ': THE' THE· .~.... " . ,'. '....... .. ." .. ·0·• ••... ....••... '. ... .>~..•••........",-, j. ', .. ;;. •••••.•. :••.j.•...••, •.•••.•.••. :.. " " '''', -'... ', . ..'.. .. ...~ ~ European Commission Directorate-General for Development Unit 'Communications, publications and The ACP-EU Courier' rue de la Loi 200, B-1049 Brussels Telephone: 299 30 62 - Fax: 299 25 25 Manuscript completed in December 1994. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1995 © ECSC-EC-EAEC Brussels • Luxembourg, 1995 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Germany CONTENTS _________ ] Introduction 3 The European Union and Development Co-operation 4 The Union in Europe and in the World The Lome Convention and the Association of the Overseas Countries and 4 Territories with the Union The Caribbean and the European Union 6 Economic and political situation of the Caribbean 6 Instruments of EU-Caribbean co-operation 8 Regional co-operation 11 Co-operation with ACP States Antigua and Barbuda 18 The Bahamas 20 Barbados 22 Belize 25 Dominica 27 Dominican Republic 30 Grenada 33 Guyana 35 Haiti 37 Jamaica 39 St Christopher and Nevis 42 St Lucia 44 St Vincent and the Grenadines 47 Suriname 50 Trinidad and Tobago 52 Co-operation with the Overseas Countries and Territories Anguilla 54 British Virgin Islands 56 Cayman Islands 58 Montserrat 59 Netherlands Antilles and Aruba 61 Turks -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

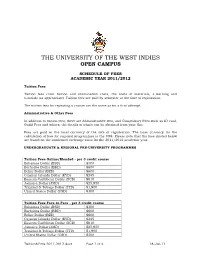

UWI Open Campus Accounts

THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES OPEN CAMPUS SCHEDULE OF FEES ACADEMIC YEAR 2011/2012 Tuition Fees Tuition fees cover tuition and examination costs, the costs of materials, e-learning and tutorials (as appropriate). Tuition fees are paid by semester at the time of registration. The tuition fees for repeating a course are the same as for a first attempt. Administrative & Other Fees In addition to tuition fees, there are Administrative fees, and Compulsory Fees such as ID card, Guild Fees and others; the details of which can be obtained from your Site. Fees are paid in the local currency of the Site of registration. The base currency for the calculation of fees for regional programmes is the US$. Please note that the fees quoted below are based on the confirmed exchange rates for the 2011/2012 academic year. UNDERGRADUATE & REGIONAL PRE-UNIVERSITY PROGRAMMES Tuition Fees Online/Blended - per 3 credit course Bahamas Dollar (BSD) $300 Barbados Dollar (BBD) $600 Belize Dollar (BZD) $600 Cayman Islands Dollar (KYD) $245 Eastern Caribbean Dollar (XCD) $810 Jamaica Dollar (JMD) $25,950 Trinidad & Tobago Dollar (TTD) $1,900 United States Dollar (USD) $300 Tuition Fees Face-to-Face - per 3 credit course Bahamas Dollar (BSD) $300 Barbados Dollar (BBD) $600 Belize Dollar (BZD) $600 Cayman Islands Dollar (KYD) $245 Eastern Caribbean Dollar (XCD) $810 Jamaica Dollar (JMD) $25,950 Trinidad & Tobago Dollar (TTD) $1,900 United States Dollar (USD) $300 Tuition&Fees 2011-2012.docx Page 1 of 4 18-Jul-11 BEd Literacy BEd Secondary Tuition Fees - per credit. -

Logistical Information

Logistical Information Meeting: Caribbean Safe School Ministerial Forum Date: 3rd - 4th April, 2017 Meeting Location: Halcyon by Rex Resort Contact: For general information related to the Forum: Ms. Sandra Amlang Programme Office UNISDR – Regional Office for the Americas Email: [email protected], Tel: +507 317 1120 Ms. Jeannette Mason Knowledge Base Officer 1 Ministry of Education, Science and Technology Antigua and Barbuda Email: [email protected], Tel: +1 268 463 5547 Ms. Gayle Drakes Education and Training Specialist CDEMA Email: [email protected], Tel: +1 246 434 4880 For room reservation at the Halcyon Cove (Rex Resorts): Mr. Renato Wilson Hotel Accountant Email: [email protected] Tel: +1 268 736 6893 Alternatively, you can contact Mr. Phil George, Communications Officer in the Ministry of Education in Antigua and Barbuda who will transmit the information to hotel on behalf of the participants. Email: [email protected] Tel: +1 268 464 7034 Caribbean Safe School Ministerial Forum: 3-4April 2017, Antigua and Barbuda General informationon Antigua and Barbuda Antigua (pronounced An-tee'ga) and Barbuda is a twin-island country in the Americas, lying 2 between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The country is located in the middle of the Leeward Islands in the Eastern Caribbean, roughly 17 degrees north of the equator. To the south are the islands of Montserrat and Guadaloupe, and to the north and west are Nevis, St. Kitts, St. Barts, and St. Martin. Antigua, the largest of the English-speaking Leeward Islands, is about 14miles (23 km)long and 11 miles (18km) wide, encompassing 108 square miles (414 km²). -

2020 International Payments Guide

2020 International Payments Guide Your Guide to Global Payments Requirements International Payments Guide Last Updated 12.2020 Table of Contents / Currency Selection Table of Contents / Currency Selection Glossary ...................................................................... 5 Cameroon ................................................................. 26 Afghanistan ................................................................ 6 Canada ...................................................................... 26 Aland Islands ............................................................. 6 Cape Verde Islands ................................................. 27 Albania ........................................................................ 7 Central Africa (BEAC) ............................................. 28 Algeria ......................................................................... 8 Central African Republic ........................................ 30 Andorra ....................................................................... 8 CFP Franc ................................................................. 30 Angola ......................................................................... 9 Chad .......................................................................... 31 Anguilla ....................................................................... 9 Chile ........................................................................... 32 Antigua and Barbuda ................................................ 9 China (Offshore) -

Economic Activity Caribbean Community Countries

ECLA/POS 76/6 ECONOMIC ACTIVITY — 1975 — CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY COUNTRIES UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA OFFICE FOR THE CARIBBEAN ECLA/POS 76/6 Dates 15 August 1976 ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA Office for the Caribbean ECONOMIC ACTIVITY « 1975 - CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY COUNTRIES (Prepared by Mr0 ¥0L. Whittingham with the assistance of Mr«, Ho Francis and Mr, McD» Rodney - Research Assistants) FEEFAOE This is the fifth publication under the title Economic Activity - Caribbean Community Countries» As in previous issues emphasis is placed on the most recent period, in this case 1975» but revisions for earlier years are also incorporated,, In addition, there is some increase in the scope and coverage of the Survey partly in response to comments on previous issues» It should be noted that the Bahamas is included for the first time this year® A separate Country Note has also been prepared for Grenada for the first timea Previously Grenada was included in the Section dealing with the West Indies Associated States» Despite the limitations of the data, the publication bringing together as it does data on all the CAE!COM countries, appears to meet some of the needs of Governments and business offices« as well as regional and other organizations interested in economic and social developments in the Caribbean sub-regions. 15 August 1976 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i - iv PART Is SUB-REGIONAL SUMMARY A. EVOLUTION OF REGIONAL INTEGRATION 1 - 6 Bo SUMMARY OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY IN THE CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY AREA THE DOMESTIC SECTOR -

(Pdf 13.8Mb) 2021 Regional Calendar

Be the solution. PwC in the Caribbean 2021 © 2021 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. At PwC, our purpose is to build trust in society and solve important problems. We’re a network of firms in 155 countries with more than 284,000 people who are committed to delivering quality in assurance, advisory and tax services. Find out more and tell us what matters to you by visiting us at www.pwc.com/cb. Hello, tomorrow! A very happy new year to you, your family This year, we are focused on a number of Culture: Redoubling our efforts to foster a and loved ones. From all of us at PwC in the key priorities. PwC culture where everyone feels valued, Caribbean, we wish you the very best for Quality: There is now an even greater focus listened to and has the opportunity to 2021. on trust in institutions, trust in information grow and succeed. To this end, we have As we reflect on the past year and the and increased transparency. Investing in launched Diversity and Inclusion councils in unprecedented health, safety and economic the enhancement of the quality of all of the each of our territories to drive the inclusivity crisis brought on by the COVID-19 services we provide remains our number agenda. pandemic, our hearts go out to all who have, one priority. Climate: The climate emergency has never and continue to be impacted. -

EXCHANGE RATE POLICY in the EASTERN CARIBBEAN by William Loehr Loehr and Associates, Inc. 1580 Garst Lane Ojai, CA 93023 (8

EXCHANGE RATE POLICY IN THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN by William Loehr Loehr and Associates, Inc. 1580 Garst Lane Ojai, CA 93023 (805) 646-4122 (0s) for US AID RDO/C Bridgetown, Barbados Under Contract: 538-0000-C-00-6012- March 10, 1986 INDEX Page Executive Summary Section 1: Introduction Section 2: An Assessment of Overvaluation of the EC Dollar 3 2.1 Concepts 3 2.2 Findings: Exchange Market Conditions 8 2,3 Findings: Real Exchange Rate 12 2.4 An Assessment 27 Section 3: Real Exchange Rates in The OECS 30 3.1 Real Exchange Rates 30 3.2 Nominal and Real Effective Exchange Rates 44 3.3 Real Effective Exchange Rate Results 51 3.4 Summary 64 Section 4: Exchange Market Options 65 4.1 Introduction 65 4.2 The Devaluation Option 69 4.3 Alternative Exchange Regime Arrangements 91 4.4 Summary 99 Section 5: Non-Exchange Market Options 103 5.1 Non-Exchange Market Policies 103 5.2 Problem Countries 107 5.3 Summary 112 Section 6: Conclusions and Recommendations 113 6.1 Conclusions 113 6.2 Recommendations 114 Bibliography 117 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This research was designed to determine whether or not the Eastern Caribbean dollar ( EC dollar ) is overvalued and whether AID should be advocating a devaluation of the EC dollar. A secondary concern was with the alternative forms that the exchange regime for the EC dollar could take. The EC dollar has been pegged to the U.S. dollar since 1976 at the rate of EC$ 2.70 = US$ 1.00. Alternatives include devaluation of that peg, pegging to some other standard or allowing the EC dollar to float. -

Currency Codes CRC Costa Rican Colon LY D Libyan Dinar SCR Seychelles Rupee

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes CRC Costa Rican Colon LY D Libyan Dinar SCR Seychelles Rupee ALL Albanian Lek HRK Croatian Kuna LT L Lithuanian Litas SLL Sierra Leonean Leone DZD Algerian Dinar CZK Czech Koruna MKD/FYR Macedonia Denar SGD Singapore Dollar AMD Armenian Dram DKK Danish Krone MOP Macau Pataca SBD Solomon Islands Dollar AOA Angola Kwanza DJF Djibouti Franc MGA Madagascar Ariary ZAR South African Rand AUD Australian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MWK Malawi Kwacha SSP South Sudanese Pound AWG Arubian Florin XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SRD Suriname Dollar AZN Azerbaijan Manat EGP Egyptian Pound MRU Mauritanian Olguiya SEK Swedish Krona BSD Bahamian Dollar EUR EMU Euro MUR Mauritius Rupee SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BHD Bahraini Dinar ERN Eritrea Nakfa MXN Mexican Peso CHF Swiss Franc BBD Barbados Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MDL Maldavian Lieu LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BYN Belarus Ruble FJ D Fiji Dollar MNT Mongolian Tugrik TWD Taiwan New Dollar BZD Belize Dollar GMD Gambian Dalasi MZN Mozambique Metical TJS Tajikistani Somoni BMD Bermudian Dollar GEL Georgian Larii MYR Malaysian Ringgit TZS Tanzanian Shilling BTN Bhutan Ngultram GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal MMK Burmese Kyat TOP Tongan Pa’anga BOB Bolivian Boliviano GNF Guinea Republic Franc NAD Namibian Dollar TTD Trinidad and Tobago Dollar BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GYD Guyana Dollar ANG Netherlands Antillean Guilder TRY Turkish Lira BWP Botswana Pula HTG Haitian Gourde NPR Nepal Rupee TMT Turkmenistani Manat BRL Brazilian Real HNL Honduran Lempira NZD New Zealand Dollar AED U.A.E. -

Long-Term Economic Prospects of the Oecs Countries

ReportNo. 805&CRG Long-TermEconomic Prospects of the OECSCountries February15, 1990 Public Disclosure Authorized CaribbeanDivision CountryDepartment IIl LatinAmerica and theCaribbean Region FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof theWorld Bank Thisdocument has a restricteddistribution and may be usedby recipients Public Disclosure Authorized only in the performanceof their officialduties. Its contentsmay not otherwise bedisclosed without World Bankauthorization. - -~ CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit - Eastern CaribbeanDollar (EC$) Upon its creation in 1965, the Eastern Caribbean dollar was tied to sterling at the rate of L - EC$4.8. in July 1976, the link with sterlingwas broken and the Eastern Caribbeandollar was aligned with'the US dollar at the rate US$l = EC$2.70. Exchange Rate as of July 1976 US$1 = EC$2.70 EC$1 = US$0.3704 OECS COUNTRIES'FISCAL YEAR April 1 - March 31 FOROMCIAL USE ONLY This report is based on the findings of a World Bank economic mission which visited the Organizationof Eastern CaribbeanStates' (OECS) countrieswhich are members of the World Bank--Antiguaand Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines--duringJanuary-February 1989. The mission was comprisedof Messrs. Alasdair Sinclair (Chief of Mission),Alberto Herrou-Aragon (Macroeconomistand AgriculturalEconomist), David Davi- (Tourism Consultant),Constantine Soumelis (EducationConsultant) and Ms. Carla Kruytbosch (ResearchAssistant). Other Bank staff members who contributed to the report include: Jose B. Sokol (Lead Economist),Alexander Yeats (TransportEconomist), Richard L. Ground (GeneralEconomist), Ms. Ginger Reich (ResearchAssistant) aad Herman von Gersdorff (Economist). CIDA supportedMr. Sinclair'swork during the report's preparation. The Caribbean DevelopmentBank contributedwith a section on Montserrat,a member of the OECS but not of the World Bank.