“Trust” in Sri Lanka's Reconciliation Process in the Post-War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Commanders of the LTTE

4/29/2016 List of commanders of the LTTE Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of commanders of the LTTE From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of commanders of theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a separatist militant Tamil nationalist organisation, which operated in northern and eastern Sri Lanka from late 1970s to May 2009, until it was defeated by the Sri Lankan Military.[1][2] Date & Place Date & Place Nom de Guerre Real Name Position(s) Notes of Birth of Death Thambi (used only by Velupillai 26 November 1954 19 May Leader of the LTTE Prabhakaran was the supreme closest associates) and Prabhakaran † Velvettithurai 2009(aged 54)[3][4][5] leader of LTTE, which waged a Anna (elder brother) Vellamullivaikkal 25year violent secessionist campaign in Sri Lanka. His death in Nanthikadal lagoon,Vellamullivaikkal,Mullaitivu, brought an immediate end to the Sri Lankan Civil War. Pottu Amman alias Shanmugalingam 1962 18 May 2009 Leader of Tiger Pottu Amman was the secondin Papa Oscar alias Sivashankar † Nayanmarkaddu[6] (aged 47) Organization Security command of LTTE. His death was Sobhigemoorthyalias Kailan Vellamullivaikkal Intelligence Service initially disputed because the dead (TOSIS) and Black body was not found. But in Tigers October 2010,TADA court judge K. Dakshinamurthy dropped charges against Amman, on the Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, accepting the CBI's report on his demise.[7][8] Selvarasa Shanmugam 6 April 1955 Leader of LTTE since As the chief arms procurer since Pathmanathan (POW) Kumaran Kankesanthurai the death of the origin of the organisation, alias Kumaran Tharmalingam Prabhakaran. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

C.A WRIT 76/2013 Shahul Hameed

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application under Article 140 of the Constitution for a mandate in the nature of a Writ of Certiorari. 1. Shahul Hameed Mohamed Jawahir No. 307/2, Kottawatta, Mawanella. Case No. CA (Writ) 76/2013 1A. Mohamed Zawahir Mohamed Arshad No. 307/2, Kottawatta, Mawanella. 2. Abdul Wahid Siththy Sifaya No. 4, Walauwatta, Mawanella. 3. M. R. Yasmin Dhanuka Bandara No. 198/4, Heerassagala Road, Kandy. 4. Mohamed Ismail Yoosuf Ali No. 214, Main Street, Mawanella. 5. Mohamed Rashid Siththy Shereena No. A 56/1, Uyanwatta, Dewanagala. 6. Mohamed Rashid No. 160, Kiringadeniya, Mawanella. 7. Mohamed Rashid Sithy Raliya Beligammana, Mawanella. 8. Mohamed Rashid Siththy Ayesha Kiringadeniya, Mawanella. 9. Mohamed Naleer Mohamed Rishan No. 52, Thakkiya Road, Mawanella. 10. Abdul Azeez Fareeda Umma No. 105, Thakkiya Road, Mawanella. Page 1 of 12 11. P. M. M. Sheriff Liyauddeen Thakkiya Road, Mawanella. 12. Mohamed Sheriff Abdul Saleem No. 21/4, Thakkiya Road, Mawanella. 13. Abdul Sameed Mohamed Nawaz Trustee, Masjid Jennah Jumma Mosque, Rabukkana Road, Mahawatte, Mawanella. 14. Hisbul‐Islam Trust No. 204/1, Dematagoda Road, Sri Vajiragnana Mawatha, Colombo 9. 15. Mohamed Sali Ahamed Jalaldeen No. 21, Waluwatta, Mawanella. 15A. Mohamed Jalaldeen Mohamed Irfan No. 21, Waluwatta, Mawanella. Petitioners Vs. 1. Hon. Minister of Lands and Development Ministry of Lands and Development, “Mihikatha Medura”, No. 1200/6, Rajamalwatte Road, Battaramulla. 2. Divisional Secretary, Mawanella. 3. Mawanella Pradeshiya Sabha, Mawanella. Respondents Page 2 of 12 Before: Janak De Silva J. N. Bandula Karunarathna J. -

Sri Lanka Eligibility

UNHCR ELIGIBILITY GUIDELINES FOR ASSESSING THE INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION NEEDS OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS FROM SRI LANKA United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) April 2009 NOTE UNHCR Eligibility Guidelines are issued by the Office to assist decision-makers, including UNHCR staff, Governments and private practitioners, in assessing the international protection needs of asylum-seekers from a given country. They are authoritative legal interpretations of the refugee criteria in respect of specific groups on the basis of objectively assessed social, political, economic, security, human rights, and humanitarian conditions in the country of origin concerned. The pertinent protection needs are analyzed in detail and recommendations made as to how the applications in question should be decided upon in line with the relevant principles and criteria of refugee law as per, notably, the 1951 Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the UNHCR Statute and relevant regional instruments such as the Cartagena Declaration, the 1969 OAU Convention and the EU Asylum Directives. The recommendations may also touch upon, as relevant, complementary or subsidiary protection regimes. UNHCR issues its Eligibility Guidelines pursuant to its responsibility to promote the accurate interpretation and application of the above-mentioned refugee criteria as envisaged by Article 8 of its Statute, Article 35 of the 1951 Convention and Article II of its 1967 Protocol and based on the expertise it has developed over several years in eligibility and refugee status determination matters. It is expected that the positions and guidance contained in the Guidelines should be weighed heavily by the relevant decision-making authorities in reaching a decision on the asylum applications concerned. -

Kapila D. Silva

KAPILA D. SILVA School of Architecture, Design & Planning, University of Kansas, 1465 Jayhawk Blvd, Lawrence, KS 66045, USA. (E) [email protected] (T) 785-864-1150 (F) 785-864-5393 (M) 414-334-1290 EDUCATION Ph.D., Architecture, 2004 University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA Post Graduate Diploma, Architectural Conservation of Monuments and Sites, 1995 University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka M.S., Architecture, 1993 University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka B.S., Built Environment, 1990 University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka with First Class Honors (equivalent of Summa cum laude) Licensures, Certifications, and Professional Training World Heritage Site Management - Their Tangible and Intangible Aspects, United Nations Institute for Training & Research and the International Council for Monuments & Sites; Hiroshima, Japan. March 12 - 17, 2006 Professional Registration; Chartered Member, Institute of Architects, Sri Lanka, 1995 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Academic University of Kansas, USA Associate Professor, August 2014 - Present Affiliated Faculty; Center for Global and International Studies, 2009 - Present Associate Faculty; Center for East Asian Studies, 2009 - Present Assistant Professor; School of Architecture, Design & Planning, August 2008 - May 2014 Visiting Assistant Professor; School of Architecture & Urban Planning, August 2007 - May 2008 University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA Visiting Assistant Professor; School of Architecture & Urban Planning, August 2005 - May 2007 Graduate Teaching Assistant; School of Architecture & Urban Planning, Fall 2004 Graduate -

Volume 28.Pdf

CBRNE Terrorism Newsletter 2 «Η διεθνής τρομοκρατία θα τελειώσει μόνον όταν αποκτήσουμε το θάρρος να καθίσουμε και να μιλήσουμε με τον μουσουλμανικό κόσμο, αντί να προκαλούμε νέες κρίσεις ή να αρχίζουμε νέους πολέμους» Sir Βασίλειος Μαρκεζίνης* Καθηγητής Δικαίου (UK) * Ο Sir Βασίλειος Μαρκεζίνης διετέλεσε Καθηγητής στο Κέημπριτζ, την Οξφόρδη και το Λονδίνο, κατείχε δε, επίσης έδρα στο Λάηντεν (Ολλανδία) και στο Ώστιν του Τέξας (ΗΠΑ). Επιπλέον, έχει διδάξει σε είκοσι πέντε Πανεπιστήμια ανά τον κόσμο, έχει συγγράψει τριάντα τρία βιβλία και πάνω από εκατόν τριάντα νομικά άρθρα, τα οποία έχουν δημοσιευθεί σε νομικά περιοδικά σε ολόκληρο τον κόσμο. Τα έργα του έχουν μεταφρασθεί στα γερμανικά, γαλλικά, ιταλικά, πορτογαλικά και κινεζικά. Είναι Μέλος της Βρετανικής Ακαδημίας, Αντεπιστέλλον Μέλος της Γαλλικής Ακαδημίας και της Ακαδημίας Αθηνών, Ξένος Εταίρος της Βελγικής, της Ολλανδικής και της Ιταλικής (Academia dei Lincei) Ακαδημίας, όπως επίσης και του Αμερικανικού Ινστιτούτου Δικαίου. Από το 1997 φέρει τον τίτλο του Επίτιμου Συμβούλου της Βασίλισσας της Αγγλίας (Queen's Counsel), ενώ από το 2000 είναι Ειδικός Επιστημονικός Σύμβουλος του Πρώτου Προέδρου του Γαλλικού Ακυρωτικού (Cour de Cassation). Το 2005 έλαβε τον τίτλο του Ιππότη από τη Βασίλισσα Ελισάβετ ΙΙ για τις εξαίρετες υπηρεσίες που έχει προσφέρει στις διεθνείς νομικές σχέσεις. Επιπλέον, έχει λάβει εξαιρετικά υψηλές τιμές από τους Προέδρους Μιτεράν και Σιράκ (της Γαλλίας), Σκάλφαρο και Τσιάμπι (της Ιταλίας) και φον Βάιτσκερ και Χέρτσοκ (της Γερμανίας). Τέλος, από το 2007 είναι Μέλος του Διοικητικού Συμβουλίου του Κοινωφελούς Ιδρύματος «Αλέξανδρος Σ. Ωνάσης». Μ ΒΡΕΤΑΝΙΑ Εκλογή πρώτου μουσουλμάνου υπουργού Ο μουσουλμάνος Shahid Malik εξελέγη πρόσφατα Υπουργός Δικαιοσύνης στη Μ Βρετανία – προφανώς στα πλαίσια της ειρηνικής συνεχιζόμενης μουσουλμανοποίη- σης της Ευρώπης την οποία ακόμη οι περισσότεροι από εμάς δεν έχουμε συνειδητοποιήσει. -

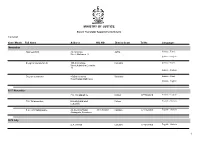

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh*

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh* If we do not end war – war will end us. Everybody says that, millions of people believe it, and nobody does anything. – H.G. Wells 1 The Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapakse finally ended the Eelam War2 in May 2009 – though, perhaps, not in the manner many would desire. So determined was the President that he had told Roland Buerk of the BBC in an interview published on February 21, 2007, “I don't want to pass this problem on to the next generation.”3 Though the final phase of open war4 began on January 16, 2008, following the January 2 unilateral withdrawal of the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) from the Norway-brokered * Ajit Kumar Singh, Research Fellow, Institute for Conflict Management 1 Things to Come (The film story), Part III, adapted from his 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, spoken by the character John Cabal. 2 The civil war in Sri Lanka can be divided into four phases: Eelam War I between 1983 and 1987, Eelam War II between 1990-1994, Eelam War III between 1995-2001, and Eelam War IV between 2006-2009. See Muttukrishna Sarvananthaa in “Economy of the Conflict Region in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression”, Policy Studies 44, East-West Centre, http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/ps044.pdf. 3 “No end in sight to Sri Lanka conflict”, February 21, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6382787.stm. 4 Amantha Perera, “Sri Lanka: Open War”, South Asia Intelligence Review, Volume 6, No.28, http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/sair/Archives/6_28.htm#assessment1. -

Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL)* **

A/HRC/30/CRP.2 Advance Version Distr.: Restricted 16 September 2015 English only Human Rights Council Thirtieth session Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL)* ** * Reproduced as received ** The information contained in this document should be read in conjunction with the report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights- Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka (A/HRC/30/61). A/HRC/30/CRP.2 Contents Paragraphs Page Part 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–13 5 II. Establishment of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), mandate and methodology ............................................................................................................. 14–46 7 III. Contextual background ........................................................................................... 47–103 12 IV. Overview of Government, LTTE and other armed groups...................................... 104–170 22 V. Legal framework ..................................................................................................... 171–208 36 Part 2– Thematic Chapters VI. Unlawful killings ..................................................................................................... 209–325 47 VII. Violations related to the -

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Nirekha De Silva Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Methodology 11 List of Abbreviations 13 Civil War in Sri Lanka 14 Army Women 20 LTTE Women 34 Peace and the process of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration 45 Human Needs and Human Rights in Reintegration 55 Psychological Barriers in Reintegration 68 Social Adjustment to Civil Life 81 Available Mechanisms 87 Recommendations 96 Directory of Available Resources 100 • Counselling Centres 100 • Foreign Recruitment 102 • Local Recruitment 132 • Vocational Training 133 • Financial Resources 160 • Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) 163 Bibliography 199 List of People Interviewed 204 3 4 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Meenakshi Gopinath and Sumona DasGupta of Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), India, for offering the Scholar for Peace Fellowship in 2005. -

Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Sri Lanka

A/HRC/34/20 Advance edited version Distr.: General 10 February 2017 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-fourth session 27 February-24 March 2017 Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Sri Lanka Summary The present report assesses the progress made in the implementation of Human Rights Council resolution 30/1, on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka between October 2015 and January 2017. On that basis, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights identifies efforts that need to be taken to achieve progress in the reconciliation and accountability agenda to which the Government of Sri Lanka has committed. The High Commissioner also advocates for the Government to continue meaningful consultations with relevant stakeholders on transitional justice and the reform agenda, and urges the Council to sustain its close engagement and monitoring of developments in Sri Lanka. A/HRC/34/20 Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Engagement of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and United Nations human rights mechanisms .................................................................. 3 III. Developments in reconciliation and accountability -

A Path Way of Disaster Risk Reduction Through Climate Change Adaptation in Aranayake, Sri Lanka (#495)

A Path way OF Disaster Risk Reduction through Climate Change Adaptation in Aranayake, Sri Lanka (#495) A Path way of Disaster Risk Reduction through Climate Change Adaptation in Aranayake, Sri Lanka Authors: Ms. Paridhi Rustogi – Young Professional Development Initiative Intern: GWP-SAS Ms. Kusum Athukorala, Senior Advisor, Sri Lanka Water Partnership (SLWP)/ Lanka Jalani and Regional Council Member GWP-SAS Editors: Mr. Kenge James Gunya - Knowledge Management Officer: GWP Global Secretariat Mr. Lal Induruwage - Regional Coordinator (GWP-SAS): Regional Office, Colombo, Sri Lanka Mr. Ranjith Ratanayake, Country Coordinator, Sri Lanka Water Partnership (SLWP)/Lanka Jalani Mr. Thakshila Dilhan Premaratne from SLWP provided special contribution. The views expressed in this case study do not necessarily represent the official views of GWP. July 2018 www.gwp.org/ToolBox About Global Water Partnership The Global Water Partnership’s vision is for a water secure world. Our mission is to advance governance and management of water resources for sustainable and equitable development. GWP is an international network that was created in 1996 to foster the implementation of integrated water resources management: the coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources in order to maximize economic and social welfare without compromising the sustainability of ecosystems and the environment. The GWP Network is open to all organizations that recognize the principles of integrated water resources management endorsed by the Network. It includes states, government institutions (national, regional, and local), intergovernmental organizations, international and national non-governmental organizations, academic and research institutions, private sector companies, and service providers in the public sector. The Network has 13 Regional Water Partnerships, 85 Country Water Partnerships, and more than 3,000 Partners located in 182 countries.