Sri Lanka Eligibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Commanders of the LTTE

4/29/2016 List of commanders of the LTTE Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of commanders of the LTTE From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of commanders of theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a separatist militant Tamil nationalist organisation, which operated in northern and eastern Sri Lanka from late 1970s to May 2009, until it was defeated by the Sri Lankan Military.[1][2] Date & Place Date & Place Nom de Guerre Real Name Position(s) Notes of Birth of Death Thambi (used only by Velupillai 26 November 1954 19 May Leader of the LTTE Prabhakaran was the supreme closest associates) and Prabhakaran † Velvettithurai 2009(aged 54)[3][4][5] leader of LTTE, which waged a Anna (elder brother) Vellamullivaikkal 25year violent secessionist campaign in Sri Lanka. His death in Nanthikadal lagoon,Vellamullivaikkal,Mullaitivu, brought an immediate end to the Sri Lankan Civil War. Pottu Amman alias Shanmugalingam 1962 18 May 2009 Leader of Tiger Pottu Amman was the secondin Papa Oscar alias Sivashankar † Nayanmarkaddu[6] (aged 47) Organization Security command of LTTE. His death was Sobhigemoorthyalias Kailan Vellamullivaikkal Intelligence Service initially disputed because the dead (TOSIS) and Black body was not found. But in Tigers October 2010,TADA court judge K. Dakshinamurthy dropped charges against Amman, on the Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, accepting the CBI's report on his demise.[7][8] Selvarasa Shanmugam 6 April 1955 Leader of LTTE since As the chief arms procurer since Pathmanathan (POW) Kumaran Kankesanthurai the death of the origin of the organisation, alias Kumaran Tharmalingam Prabhakaran. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

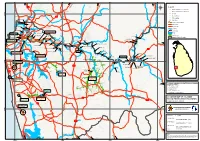

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Distribution of COVID – 19 Patients in Sri Lanka Effective Date 2020-09-11 Total Cases 3169

Distribution of COVID – 19 patients in Sri Lanka Effective Date 2020-09-11 Total Cases 3169 MOH Areas Quarantine Centres Inmates ❖ MOH Area categorization has been done considering the prior 14 days of patient’s residence / QC by the time of diagnosis MOH Areas Agalawatta Gothatuwa MC Colombo Rajanganaya Akkaraipattu Habaraduwa MC Galle Rambukkana Akurana Hanwella MC Kurunegala Ratmalana Akuressa Hingurakgoda MC Negombo Seeduwa Anuradhapura (CNP) Homagama MC Ratnapura Sevanagala Bambaradeniya Ja-Ela Medadumbara Tangalle Bandaragama Kalutara(NIHS) Medirigiriya Thalathuoya Bandarawela Katana Minuwangoda Thalawa Battaramulla Kekirawa Moratuwa Udubaddawa Batticaloa Kelaniya Morawaka Uduvil Beruwala(NIHS) Kolonnawa Nattandiya Warakapola Boralesgamuwa Kotte/Nawala Nochchiyagama Wattala Dankotuwa Kuliyapitiya-East Nugegoda Welikanda Dehiattakandiya Kundasale Pasbage(Nawalapitiya) Wennappuwa Dehiwela Kurunegala Passara Wethara Galaha Lankapura Pelmadulla Yatawatta Galgamuwa Maharagama Piliyandala Galnewa Mahawewa Polpithigama Gampaha Maho Puttalam Gampola(Udapalatha) Matale Ragama Inmates Kandakadu Staff & Inmates Senapura Staff & Inmates Welikada – Prision Quarantine Centres A521 Ship Eden Resort - Beruwala Akkaraipaththu QC Elpiitiwala Chandrawansha School Amagi Aria Hotel QC Fairway Sunset - Galle Ampara QC Gafoor Building Araliya Green City QC Galkanda QC Army Training School GH Negombo Ayurwedic QC Giragama QC Bambalapitiya OZO Hotel Goldi Sands Barana camp Green Paradise Dambulla Barandex Punani QC GSH hotel QC Batticaloa QC Hambanthota -

Figure 1.1.5 Boralesgamuwa South Sub-Basin A7

N Old Kesbewa Road High Level Road Boralesgamuwa Wewa Rattanapitiya Ela Maharagama-Dehiwala Road Weras Ganga Colombo-Piliyandala Road Maha Ela Legend Scale 0 200 400 600 800 m Boundary of Sub-basin Principal Drainage Channel Urban Drainage Channel The Study on Storm Water Drainage Plan Figure 1.1.5 for the Colombo Metropolitan Region Boralesgamuwa South Sub-basin in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY A7 - F5 JAPAN INTERNATIONALCOOPERATION AGENCY in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka N The Study on Storm Water Drainage Plan Drainage Water onStorm Study The for the Colombo Metropolitan Region Metropolitan Colombo the for High Level Road Colombo-Piliyandala Road Maha Ela A7 -F6 Maha ElaSub-basin Figure 1.1.6 Legend Boundary of Sub-basin Principal Drainage Channel Weras Ganga Small Stream or Irrigation Creek Moratuwa-Piliyandala Road Scale 0 400 800 1200 1600 2000 m Kospalana Bridge N Ratmalana Airport Borupana Bridge Kandawala Telawala Weras Ganga Legend Boundary of Sub-basin Kospalana Katubedda Bridge Minor Tributaries Scale 0 200 400 600 800 m The Study on Storm Water Drainage Plan Figure 1.1.7 for the Colombo Metropolitan Region Ratmalana-Moratuwa Sub-basin in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY A7 - F7 N Colombo-Piliyandala Road Borupana Bridge Maha Ela Weras Ganga Moratuwa-Piliyandala Road Kospalana Bridge Legend Scale Boundary of Sub-basin 0 200 400 600 800 m Minor Tributary or Creek The Study on Storm Water Drainage Plan -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

Volume 28.Pdf

CBRNE Terrorism Newsletter 2 «Η διεθνής τρομοκρατία θα τελειώσει μόνον όταν αποκτήσουμε το θάρρος να καθίσουμε και να μιλήσουμε με τον μουσουλμανικό κόσμο, αντί να προκαλούμε νέες κρίσεις ή να αρχίζουμε νέους πολέμους» Sir Βασίλειος Μαρκεζίνης* Καθηγητής Δικαίου (UK) * Ο Sir Βασίλειος Μαρκεζίνης διετέλεσε Καθηγητής στο Κέημπριτζ, την Οξφόρδη και το Λονδίνο, κατείχε δε, επίσης έδρα στο Λάηντεν (Ολλανδία) και στο Ώστιν του Τέξας (ΗΠΑ). Επιπλέον, έχει διδάξει σε είκοσι πέντε Πανεπιστήμια ανά τον κόσμο, έχει συγγράψει τριάντα τρία βιβλία και πάνω από εκατόν τριάντα νομικά άρθρα, τα οποία έχουν δημοσιευθεί σε νομικά περιοδικά σε ολόκληρο τον κόσμο. Τα έργα του έχουν μεταφρασθεί στα γερμανικά, γαλλικά, ιταλικά, πορτογαλικά και κινεζικά. Είναι Μέλος της Βρετανικής Ακαδημίας, Αντεπιστέλλον Μέλος της Γαλλικής Ακαδημίας και της Ακαδημίας Αθηνών, Ξένος Εταίρος της Βελγικής, της Ολλανδικής και της Ιταλικής (Academia dei Lincei) Ακαδημίας, όπως επίσης και του Αμερικανικού Ινστιτούτου Δικαίου. Από το 1997 φέρει τον τίτλο του Επίτιμου Συμβούλου της Βασίλισσας της Αγγλίας (Queen's Counsel), ενώ από το 2000 είναι Ειδικός Επιστημονικός Σύμβουλος του Πρώτου Προέδρου του Γαλλικού Ακυρωτικού (Cour de Cassation). Το 2005 έλαβε τον τίτλο του Ιππότη από τη Βασίλισσα Ελισάβετ ΙΙ για τις εξαίρετες υπηρεσίες που έχει προσφέρει στις διεθνείς νομικές σχέσεις. Επιπλέον, έχει λάβει εξαιρετικά υψηλές τιμές από τους Προέδρους Μιτεράν και Σιράκ (της Γαλλίας), Σκάλφαρο και Τσιάμπι (της Ιταλίας) και φον Βάιτσκερ και Χέρτσοκ (της Γερμανίας). Τέλος, από το 2007 είναι Μέλος του Διοικητικού Συμβουλίου του Κοινωφελούς Ιδρύματος «Αλέξανδρος Σ. Ωνάσης». Μ ΒΡΕΤΑΝΙΑ Εκλογή πρώτου μουσουλμάνου υπουργού Ο μουσουλμάνος Shahid Malik εξελέγη πρόσφατα Υπουργός Δικαιοσύνης στη Μ Βρετανία – προφανώς στα πλαίσια της ειρηνικής συνεχιζόμενης μουσουλμανοποίη- σης της Ευρώπης την οποία ακόμη οι περισσότεροι από εμάς δεν έχουμε συνειδητοποιήσει. -

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh*

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh* If we do not end war – war will end us. Everybody says that, millions of people believe it, and nobody does anything. – H.G. Wells 1 The Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapakse finally ended the Eelam War2 in May 2009 – though, perhaps, not in the manner many would desire. So determined was the President that he had told Roland Buerk of the BBC in an interview published on February 21, 2007, “I don't want to pass this problem on to the next generation.”3 Though the final phase of open war4 began on January 16, 2008, following the January 2 unilateral withdrawal of the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) from the Norway-brokered * Ajit Kumar Singh, Research Fellow, Institute for Conflict Management 1 Things to Come (The film story), Part III, adapted from his 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, spoken by the character John Cabal. 2 The civil war in Sri Lanka can be divided into four phases: Eelam War I between 1983 and 1987, Eelam War II between 1990-1994, Eelam War III between 1995-2001, and Eelam War IV between 2006-2009. See Muttukrishna Sarvananthaa in “Economy of the Conflict Region in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression”, Policy Studies 44, East-West Centre, http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/ps044.pdf. 3 “No end in sight to Sri Lanka conflict”, February 21, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6382787.stm. 4 Amantha Perera, “Sri Lanka: Open War”, South Asia Intelligence Review, Volume 6, No.28, http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/sair/Archives/6_28.htm#assessment1. -

Location Map of Colombo Flood Protection Structures

o a a a l b y w i e r m u e w i o b w d g m i l n e a t e i t r N i i N W E 03 K o Legend o T o T T o T .! Major Flood Protection Structures Kadawata ® .! Minor Flood Protection Structures 0 0 0 V# Anicuts 0 0 P 2 u d g Salinity Barrier Hendala A 1 o d a O O b River Gauges u y t a e Wattala Gate r )" C Unit Offices i r c u l a Flood Protection Bunds .! r Hekitta .! H i g Wattala Bund h Expressway w a Thelangapatha y Major Roads .! Kelaniya Kelani G .! anga Streams Oliyamulla Peliyagoda Tank Bunds .! Kelani North Bund Hatharekanuwa Tanks Nagalagam Gauge Pethiyagoda Unit Office Irrigable Area b Pethiyagoda )" Jemagewattha Akaravita .! .! )" a Irrigation Division Boundary North Lock Gate ! Talwattha y .! . O .! u r .! .! u Kahatapitiya 1 h Nagalagam Unit Office Lanarol Mawatha a Rada Ela P (Flood Controling Unit) Salinity Barrier Bund Kahatapitiya 2 .! .! Sedawatha Kongahamula .! Bund Hewagama .! .! Ranwela Mutthetupola To Awissawella Kelanimulla Nirmawila .! d .! .! .! Lanarol Mawatha .! .! Madapena Ambathale (existing) Weliwita .! A 4 Colombo .! .! Ambathale New Ambathale Bund Bomiriya Undugoda Kelani South Bund Korathota Suduwila Giraimbula Kaduwela .! .! Gothatuwa Bund Brandigampola 2 Hanwella Gauge Uruwala Ranala .! Brandigampola 1 .! Kollupitiya Pallewela Anicut V# .! Henpita 0 .! .! 0 V# .! 0 Irrigation Department 0 b 9 Premises 1 .! Bambalapitiya Pollatthawela E 02 Niripola Anicut .! Wanahagoda (Damaged) V# 9 Bay Anicut Dasawella Bund Narahenpita Hettige Oya Awirihena Tank Unit Office A 2 Sri Jayawardanepura )" Aatigala V#Pallekumbura Anicut Thalangama Wa k O Parliament Tank ya Hettige Oya Wellawatta Irrigation Scheme Quaters Nugegoda Schemes maintained by the Divisional Irrigation To Labugama Engineer's Office 1. -

Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL)* **

A/HRC/30/CRP.2 Advance Version Distr.: Restricted 16 September 2015 English only Human Rights Council Thirtieth session Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL)* ** * Reproduced as received ** The information contained in this document should be read in conjunction with the report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights- Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka (A/HRC/30/61). A/HRC/30/CRP.2 Contents Paragraphs Page Part 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–13 5 II. Establishment of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), mandate and methodology ............................................................................................................. 14–46 7 III. Contextual background ........................................................................................... 47–103 12 IV. Overview of Government, LTTE and other armed groups...................................... 104–170 22 V. Legal framework ..................................................................................................... 171–208 36 Part 2– Thematic Chapters VI. Unlawful killings ..................................................................................................... 209–325 47 VII. Violations related to the -

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka

Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Nirekha De Silva Transitional Justice for Women Ex-Combatants in Sri Lanka Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Preface 7 Introduction 9 Methodology 11 List of Abbreviations 13 Civil War in Sri Lanka 14 Army Women 20 LTTE Women 34 Peace and the process of Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration 45 Human Needs and Human Rights in Reintegration 55 Psychological Barriers in Reintegration 68 Social Adjustment to Civil Life 81 Available Mechanisms 87 Recommendations 96 Directory of Available Resources 100 • Counselling Centres 100 • Foreign Recruitment 102 • Local Recruitment 132 • Vocational Training 133 • Financial Resources 160 • Non-Government Organizations (NGO’s) 163 Bibliography 199 List of People Interviewed 204 3 4 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr. Meenakshi Gopinath and Sumona DasGupta of Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP), India, for offering the Scholar for Peace Fellowship in 2005. -

Dietary Habits of Varanus Salvator Salvator in Sri Lanka with a New Record of Predation on an Introduced Clown Knifefish,Chitala Ornata

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Herpetological Bulletin 133, 2015: 23-28 Dietary habits of Varanus salvator salvator in Sri Lanka with a new record of predation on an introduced clown knifefish,Chitala ornata DISSANAYAKA M. S. S. KARUNARATHNA1*, THILINA D. SURASINGHE2, MAHESH C. DE SILVA3, MAJINTHA B. MADAWALA4, DINESH E. GABADAGE5 & WELATHANTHRIGE M. S. BOTEJUE5 1Nature Explorations and Education Team, No: B-1 / G-6, De Soysapura, Moratuwa 10400, Sri Lanka 2Department of Biology, Rhodes College, Memphis, TN 38112, USA 3Young Zoologists’ Association, Department of National Zoological Gardens, Dehiwala, Sri Lanka 4South Australian Herpetology Group, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia 5Biodiversity Conservation Society, 150/6 Stanley Thilakarathne Mawatha, Nugegoda 10250, Sri Lanka *Corresponding author email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Two species of monitor lizard (Varanus) occur in Sri Lanka: Our study indicates that prey selection of V. s. salvator is V. salvator salvator (water monitor) and V. bengalensis (land much broader than previously reported in the literature. We monitor). The nominotypic form V. s. salvator is endemic found a total of 102 food items that have been observed (Koch et al., 2007) and the largest species of lizard in Sri Lanka predated/consumed by V. s. salvator in Sri Lanka (Table 1). with the longest individual recorded being 321 cm in total Among these, 86 (84.3%) were vertebrates, and 16 (15.7%) length (Bennett, 1998). V. s. salvator are generally found in invertebrates. Vertebrate prey included four species of aquatic habitats including freshwater swamps, ditches, tanks, amphibian (3.9%), 18 species of reptile (17.7%) including streams, reservoirs, ponds, rivers, mangroves and coastal highly toxic snakes, for example Daboia russelii and Naja marshes areas. -

Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Sri Lanka

A/HRC/34/20 Advance edited version Distr.: General 10 February 2017 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-fourth session 27 February-24 March 2017 Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Sri Lanka Summary The present report assesses the progress made in the implementation of Human Rights Council resolution 30/1, on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka between October 2015 and January 2017. On that basis, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights identifies efforts that need to be taken to achieve progress in the reconciliation and accountability agenda to which the Government of Sri Lanka has committed. The High Commissioner also advocates for the Government to continue meaningful consultations with relevant stakeholders on transitional justice and the reform agenda, and urges the Council to sustain its close engagement and monitoring of developments in Sri Lanka. A/HRC/34/20 Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Engagement of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and United Nations human rights mechanisms .................................................................. 3 III. Developments in reconciliation and accountability