Afghanistan Shaun Gladwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSI of NSW Article

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article USI Vol60 No1 Mar09 19/2/09 2:23 PM Page 9 BIOGRAPHY Trooper Mark Gregor Strang Donaldson, VC Special Air Service Regiment 8248070 Trooper Mark Gregor Strang Donaldson has been awarded the Victoria Cross for Australia for most conspicuous acts of gallantry in action in a circumstance of great peril in Afghanistan as part of the Special Operations Task Group during Operation SLIPPER, Oruzgan Province, Afghanistan. Mark Donaldson was born in Waratah, Newcastle, New South Wales, on 2 April 1979. He spent his formative years in northern New South Wales where he graduated from high school in 1996. He enlisted in the Australian Army on 18 June 2002 and undertook recruit training at the Army Recruit Training Centre, Kapooka, New South Wales. He demonstrated an early aptitude for soldiering and was awarded the prizes for best shot and best at physical training in his platoon. Subsequently, he was allocated to the Royal Australian Infantry Corps and posted to the School of Infantry at Singleton, New South Wales, where he excelled in his initial employment training. -

ANNUAL NEWSLETTER 2020 CONTENTS SAS NETWORK About the Fund

ANNUAL NEWSLETTER 2020 CONTENTS SAS NETWORK About the Fund .................................................................................... 2 Chairman’s Report ............................................................................... 4 Trustees ................................................................................................ 6 Patron ................................................................................................... 7 Chief Operating Officer’s Report ........................................................ 8 Dinner Committee ............................................................................... 9 Treasurer’s Report ............................................................................... 10 The Hon Peter Blaxell by Dr Grant Walsh ............................................ 12 My Journey with the SAS Resources Trust by the Hon Peter Blaxell... 13 Educational Opportunities ................................................................... 16 Beneficiary Reflections ........................................................................ 19 Our Events ............................................................................................ 20 Event Sponsors 2019-2020 .................................................................. 23 Supporters 2019-2020 ......................................................................... 24 The Year in Review ............................................................................... 26 ABOUT THE SAS RESOURCES FUND The Special Air Service -

The Task Cards

HEROES HEROES TASK CARD 1 TASK CARD 2 HERO RECEIVES PURPLE CROSS YOUNG AUSTRALIAN OF THE YEAR The Young Australian of the Year has been awarded since 1979. It Read the story about Sarbi and answer these questions. recognises the outstanding achievement of young Australians aged 16 to 30 and the contributions they have made to our communities. 1. What colour is associated with the Australian Special Forces? YEAR Name of Recipient Field of Achievement 2011 Jessica Watson 2. What breed of dog is Sarbi? 2010 Trooper Mark Donaldson VC 2009 Jonty Bush 3. What is Sarbi trained to do? 2008 Casey Stoner 2007 Tania Major 4. What type of animal has also received 2006 Trisha Broadbridge the Purple Cross for wartime service? 2005 Khoa Do 2004 Hugh Evans 5. In which country was Sarbi working 2003 Lleyton Hewitt when she went missing? 2002 Scott Hocknull 2001 James Fitzpatrick 6. How was Sarbi identified when she was found? 2000 Ian Thorpe OAM 1999 Dr Bryan Gaensler 7. What does MIA stand for? 1998 Tan Le 1997 Nova Peris OAM 8. Which word in the text means ‘to attack by surprise’? 1996 Rebecca Chambers 1995 Poppy King 9. How many days was Sarbi missing for? Find out what each of these people received their Young Australian 10. Why did Sarbi receive the Purple cross? Award for. Use this list of achievements to help you. Concert pianist; Astronomer; Champion Tennis Player; Sailor; Palaeontologist; MotoGP World Champion; Business Woman; World Champion Swimmer; Youth Leader & Tsunami Survivor; Anti-poverty Campaigner; Olympic Gold Medallist Athlete; Victim -

Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2012–2013 Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2012–2013

Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2012–2013 Memorial Annual Report War Australian Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2012–2013 Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2012–2013 Annual report for the year ended 30 June 2013, together with the financial statements and the report of the Auditor-General Corporal Mark Donaldson VC, Mr Keith Payne VC OAM, Corporal Daniel Keighran VC, and Corporal Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG at the inaugural Last Post Ceremony. Images produced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra Cover image: Enhancements to the Dawn Service included projections on the building, and Corporal Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG (pictured) reading letters from soldiers before the service. Photo courtesy The Canberra Times. Copyright © Australian War Memorial 2013 ISSN 1441 4198 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. Australian War Memorial GPO Box 345 Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia www.awm.gov.au AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2012–2013 ii Mrs Elaine Doolan, Rear Admiral Ken Doolan AO RAN (Ret’d), Chairman of the Council of the Australian War Memorial, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Cornwall escorted by Ms Nola Anderson, then Acting Director, through the Commemorative Area. iii AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2012–2013 AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2012–2013 iv v AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL ANNUAL REPORT 2012–2013 The Honourable Julia Gillard, then Prime Minister of Australia, Her Excellency the Honourable Quentin Bryce AC CVO, the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, and Rear Admiral Ken Doolan AO RAN (Ret’d), Chairman of the Council of the Australian War Memorial viewing the Remember me: the lost diggers of Vignacourt on Remembrance Day 2012. -

JULY 2017 Vol 40 - No 2 POST the CENTENNIAL EDITIONS 2014-18

Listening JULY 2017 Vol 40 - No 2 POST THE CENTENNIAL EDITIONS 2014-18 ANZAC DAY photos ‘A hell of a day’ - the story of Troy Simmonds (Ex-SASR Sergeant) The Official Journal of The Returned & Services League of Australia WA Branch Incorporated 2 The Listening Post JULY 2017 We’ve moved! RSLWA staff are located at: Level 3 66 St Georges Terrace (beside London Court) Come and have a cuppa on us! Book a room for a Sub-Branch meeting or gathering. There are two committee rooms, two meeting rooms and an event room suitable for up to 30 people. To book, contact Matthew Holyday on 9287 3714 or [email protected] There is no booking charge for RSL events. Although staff have relocated, our phone numbers have not changed. You can find our updated email addresses on Page 3. We’re closer to the bus and train services. ANZAC Club has closed permanently clearing the way for the development of a ‘Veterans’ Centre’. In the meantime, while there is no bar facilities in our temporary premises, Members are always welcome to visit us until the new ANZAC House is opened. Google map showing location of new offices LEVEL 3, 66 ST GEORGES TERRACE, PERTH (beside London Court) www.rslwa.org.au The Listening Post JULY 2017 3 Listening JULY 2017 Vol 40 - No 2 POST contact cover THE CENTENNIAL EDITIONS 2014-18 contents Writing and Advertising Information: A Reporter’s Memory of Pictured are members 4 Royceton Hardey the Vietnam War Online and Social Media Coordinator of the 10th Light (08) 9287 3700. -

Propaganda and Military Celebrity in First World War Australia

THE ENDURING IMPACT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR A collection of perspectives Edited by Gail Romano and Kingsley Baird The Politics of Heroism: Propaganda and Military Celebrity in First World War Australia Bryce Abraham Australian War Memorial Abstract Afghanistan veteran Ben Roberts-Smith is one of the most well-known faces of modern conflict in Australia. The decorated special forces soldier is frequently at the forefront of commemorative initiatives, has become a spokesman for health and sport, and is popularly portrayed as the embodiment of the modern ‘Anzac’. But Roberts-Smith’s social currency as a hero is not a recent phenomenon. It has its origins in 1917, when decorated soldiers were first used to advertise the war effort. This was a tumultuous year for Australians deeply embroiled in the First World War. A failed conscription plebiscite—and another looming—and increasing devastation on the battlefield had led to a growing sense of war weariness. Amidst this discontent, the State Parliamentary Recruiting Committee of Victoria launched the Sportsmen’s Thousand, an army recruitment initiative designed to encourage the enlistment of athletic men. The posters released for the campaign featured a portrait of a fit, young uniformed man—Lieutenant Albert Jacka, an accomplished sportsman and decorated ‘war hero’. The Sportsmen’s Thousand used Jacka to invoke the connection between masculinity and heroism by suggesting that talent on the sports field would translate to prowess on the field of battle, just as it had for Jacka. This article explores how ‘heroes’ like Jacka were increasingly used in Australian war propaganda and recruitment initiatives from 1917 to inspire enlistment and promote a sense of loyalty to the war effort. -

Carey Community News VOLUME 26 ISSUE 1 WINTER 2016 Torchcarey Community News

TORCHCarey Community News VOLUME 26 ISSUE 1 WINTER 2016 TORCHCarey Community News TORCH Contents Vol. 26 Issue 1, Winter 2016 1 From the Principal OUR COMMUNITY Publisher 26 Community News FEATURES Carey Baptist Grammar School 28 From The Archive 349 Barkers Road, Kew Rights and Community 2 30 Philanthropy News Victoria 3101 Australia 6 By Courage and Faith 03 9816 1222 9 Courage in Action OCGA Editorial Inquiries 10 A Mission to Help 31 OCGA News Hannah Cartmel It Does Get Better A True Honour 12 32 03 9816 1386 14 Model United Nations 35 David Wansbrough OAM (1982) [email protected] 15 Making History 36 Where Are They Now? OCGA Inquiries 16 IB Diploma Programme Events 39 Reunions and Events Kate Birrell Carey Soccer Player in National Comp 17 42 Club News 03 9816 1357 44 Obituaries [email protected] NEWS IN BRIEF 46 Birth and Marriage Announcements Cover image: Brigitte Hunt (Year 10) diving in 18 Donvale 48 Community Support Program 20 Junior School Kew the Under 16 A Division at the APS diving finals 49 Contacts on 16 March 2016. Photo: Mark Westcott 22 Middle School 24 Senior School The Carey Medal The Carey Medal Committee is currently seeking nominations for the 2017 award. If you know of anyone in the Carey community – including past and current students, parents and staff, female or male – who have given exceptional and outstanding service to the wider community either within the state, nationwide or internationally, please consider nominating them for recognition with the Carey Medal. Formal nominations can be emailed to [email protected] Get in touch if you have anyone in mind and a member of the Committee will be in touch. -

February 2009 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE February 2009 VOL. 32 No.1 The official journal of THE RETURNED & SErvICES LEAGUE OF AUstrALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListeningWA Branch Incorporated • PO Box 3023 Adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • Established 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL RSL Australia Day Awards From Left; Cadet Sergeant Ashley Duckling - Australian Air Force Cadets. Cadet Petty Officer David Thatcher - Australian Navy Cadets. Cadet Under Officer Hannah Walker - Australian Army Cadets STOP PRESS Trooper The Victoria Donaldson VC Cross Library Marching in at ANZAC Perth ANZAC Day Ceremony at House 2009 Kanchanaburi Page Pages Page 8 5 19 Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL BELMONT 9373 4400 COUNTRY STORES BUNBURY SUPERSTORE 9722 6200 ALBANY - KITCHEN & LAUNDRY ONLY 9842 1855 CITY MEGASTORE 9227 4100 BROOME 9192 3399 CLAREMONT 9284 3699 BUNBURY SUPERSTORE 9722 6200 JOONDALUP SUPERSTORE 9301 4833 KATANNING 9821 1577 MANDURAH SUPERSTORE 9586 4700 COUNTRY CALLERS FREECALL 1800 654 599 MIDLAND SUPERSTORE 9267 9700 O’Connor SUPERSTORE 9337 7822 OSBORNE PARK SUPERSTORE 9445 5000 VIC PARK - PARK DISCOUNT SUPERSTORE 9470 4949 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. I put my name on it.”* Just show your membership card! 2 THE LIstENING Post February 2009 14 BERRIMAN DRIVE, WANGARA www.northsidenissan.com.au IT’S A Great moVE maKE Into A DualIS TIIDA ST THE all new seDan or DualIS st H atCH LIMIteD stoCK # # • ABS Brakes • Dual Front Airbags • Dual Airbags • CD Player $15,500 • 6 Speed Manual , $23990 • Air Conditioning # DRIVeawaY Applicable to TPI card holders only. Manual. Metallic colours $395 extra DRIVeawaY# Applicable to TPI card holders only. -

BATTLE for AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2009 5 Fld Amb Aug09 Cover:Layout 1 18/08/09 10:54 AM Page 2

5 Fld Amb Aug09 cover:Layout 1 18/08/09 10:54 AM Page 1 BATTLE FOR AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2009 5 Fld Amb Aug09 cover:Layout 1 18/08/09 10:54 AM Page 2 Supporting Australia’s veterans, peacekeepers and their families VVCS provides counselling support to veterans, peacekeepers, their families and eligible Australian Defence Force members. VVCS is a specialised, free and confi dential Australia-wide service. VVCS can provide you with: • individual, couple and family counselling • after-hours crisis telephone counselling via Veterans Line • case management services • group programs for common mental health issues – anxiety, depression, sleep and anger • psycho-educational programs for couples including a residential lifestyle management program • health promotion programs, including Heart Health a 52 week supervised exercise and health education program offered in group and correspondence formats. • Stepping Out, a 2-day ‘transition’ program for ADF members and their partners preparing to leave the military • ‘Changing the Mix’ – a self-paced alcohol reduction correspondence program, call 1800 1808 68 to register We can help you work through issues such as stress, relationship, family problems and other lifestyle issues as well as emotional or psychological issues associated with your military service. To arrange an appointment or obtain more information about VVCS please call the number below or visit our website. Call 1800 011 046* Veterans and Veterans Families Counselling Service www.dva.gov.au/health_and_wellbeing/health_programs/vvcs A service founded by Vietnam veterans *Free local call. Calls from mobile and pay phones may incur charges. 5 Fld Amb Aug09:Layout 1 18/08/09 10:59 AM Page 1 5th FIELD AMBULANCE RAAMC ASSOCIATION PATRON: Colonel Ray Hyslop OAM RFD OFFICE BEARERS PRESIDENT: Lt Col Derek CANNON RFD ~ 31 Southee Road, RICHMOND NSW 2753 ~ (H) (02) 4578 2185 HON. -

Issue107 – May 2011

CASCABEL Journal of the ROYAL AUSTRALIAN ARTILLERY ASSOCIATION (VICTORIA) INCORPORATED ABN 22 850 898 908 ISSUE 107 Published Quarterly in MAY 2011 Victoria Australia HONOURING Australian and New Zealand Defence Force head dress sit atop two Steyr assault rifles as a Flags from multiple nations fly at memorial to the ANZAC heroes, at the Turkish International Service. the Dili ANZAC Day dawn service in East Timor, 2010. THE FALLEN Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright 3 The President Writes & Membership Report 4 From The Colonel Commandant 5 Message from Lt Col Jason Cooke 5 Editor’s Indulgence 7 ANZACS on Anzac Day 2010 8 The Slouch Hat & Emu Plumes 10 Customs and Traditions 11 The forgotten heroes of war 15 Obituary Col L J Newell AM CStJ QPM ED 17 Letter of appreciation 18 Gallipoli Sniper 19 Update on AAAM, North Fort and RAAHC 22 Operation Christchurch concludes 24 A Quartermaster’s Prayer 25 Shot at future 26 Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith, VC, MG 27 Artillery reorganisation 30 90th birthday for RAAF 32 RAAF Off’s at “work”. 34 Army 110th birthday 35 Vale Cpl Richard Atkinson 37 Vale Spr Jamie Robert Larcombe 38 Hall of VC’s 39 Gunner Luncheon - Quiz 2011 40 ADF Paralympic Team 41 Gunners final mission 42 Parade Card/Changing your address? See cut-out proforma 43 Current Postal Addresses All mail for the Association, except matters concerning Cascabel, should be addressed to: The Secretary RAA Association (Vic) Inc. 8 Alfada Street Caulfield South Vic. 3167 All mail for the Editor of Cascabel, including articles and letters submitted for publication, should be sent direct to: Alan Halbish 115 Kearney Drive Aspendale Gardens Vic 3195 (H) 9587 1676 [email protected] 2 RAA Association (VIC) Inc CONTENTS AND SUBMISSIONS Committee The contents of CASCABEL Journal are President: MAJ Neil Hamer RFD determined by the editor. -

Annual Newsletter 2019 Trustees

ANNUAL NEWSLETTER 2019 TRUSTEES Greg Soloman Grant Walsh, CSM Robert Druitt Andrew Forrest, AO Chairman Deputy Chairman Treasurer Alan Cransberg Caron Sugars James McMahon, DSC, Kerry Stokes, AC DSM Dr Mark Nidorf Michelle Hawksley Nicholas Brasington Hon Peter Blaxell Peter Fitzpatrick, AO, AM Commanding Officer SAS Regiment Patron: Major General the Honourable Michael Jeffery, AC, AO(Mil), CVO, MC (Retd) Ambassadors: Corporal Mark Donaldson, VC and Corporal Ben Roberts-Smith, VC, MG Assistance Committee: Dr. Mark Nidorf, Grant Walsh, The Hon Peter Blaxell, Michelle Hawksley and Marion Smyth RN, RMHN, BA (Psych), BSW, GradCert SocSc,MSocSc DINNER COMMITTEE MEMBERS Hon Chris Ellison Andrej Karpinski Dietmar Mazanetz Geoff Baldwin Committee Chairman Mike Smith Hon Peter Blaxell Peter Boyd Ric Gloede Sally-Anne Doherty Simon Trevisan Tony Wills The Committee has a strong history of substantial support Melbourne Charity Dinner to be held on 28th February 2020 for the SAS Resources Fund (SASRF) which has been in the in the Melbourne Cricket Club at the Melbourne Cricket form of various fundraising dinners and events in Perth and Ground. This plans to be a great event and I am sure will Melbourne. I sincerely thank my fellow members of the perpetuate the success of previous functions at the MCG. Committee who generously contribute their time not only to fundraising events but to increasing awareness in the Finally, on behalf of the Committee I also extend our deep broader community to the work of the Fund. appreciation to Sharon, Jo and Tim at the SASRF office who do a fantastic job supporting us. We could not do it without I would also like to thank all the sponsors, supporters, them! volunteers and guests who attend and support our events. -

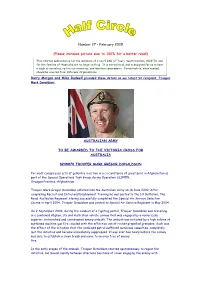

Half Circle Number 27

Number 27 – February 2009 (Please increase picture size to 150% for a better read!) This informal publication is for the members of C Coy 5 RAR (2 nd tour), South Vietnam, 1969/70, and for the families of those who are no longer with us. It is non-political, and is designed for us to have a laugh at ourselves, re-live our memories, and maintain camaraderie. Formal advice, when needed, should be sourced from Veterans’ Organisations. Barry Morgan and Mike Radwell provided these details on our latest VC recipient, Trooper Mark Donaldson: AUSTRALIAN ARMY TO BE AWARDED TO THE VICTORIA CROSS FOR AUSTRALIA 8248070 TROOPER MARK GREGOR DONALDSON For most conspicuous acts of gallantry in action in a circumstance of great peril in Afghanistan as part of the Special Operations Task Group during Operation SLIPPER, Oruzgan Province, Afghanistan. Trooper Mark Gregor Donaldson enlisted into the Australian Army on 18 June 2002. After completing Recruit and Initial and Employment Training he was posted to the 1st Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment. Having successfully completed the Special Air Service Selection Course in April 2004, Trooper Donaldson was posted to Special Air Service Regiment in May 2004. On 2 September 2008, during the conduct of a fighting patrol, Trooper Donaldson was travelling in a combined Afghan, US and Australian vehicle convoy that was engaged by a numerically superior, entrenched and coordinated enemy ambush. The ambush was initiated by a high volume of sustained machine gun fire coupled with the effective use of rocket propelled grenades. Such was the effect of the initiation that the combined patrol suffered numerous casualties, completely lost the initiative and became immediately suppressed.