Some Day All Music Will Be Made This Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Examensarbete

EXAMENSARBETE Musikalisk animation En studie i animation skapad för samverkan med musik Linnea Forslund Teknologie kandidatexamen Datorgrafik Luleå tekniska universitet Institutionen för konst, kommunikation och lärande Abstract Bachelor thesis about animation created for synchronization with music. A brief history is included. Part one is a report on the 3d-projection mapping project that I took part of as an intern at the digital creative agency North Kingdom. The other part consists of four analysis of different audiovisual works from various times and styles. The final part is a discussion of how animation relates to music, what music looks like and what the difference is between projections for a three dimensional objects and those for a flat surface, looking at both my project and these four analysis. Keywords: animation, visual music, projection mapping, VJ, computer graphics Kandidatuppsats om animation skapad för synkronisering med musik. En kortfattad historik är inkluderad. Del ett är en rapport från 3d-projektionsprojektet jag deltog i som praktikant på digitala reklambyrån North Kingdom. Den andra delen består av fyra analyser av olika audiovisuella verk från olika tider och stilar. Den sista delen är en diskussion om hur animation relaterar till musik, hur musik ser ut och vad skillnaden är mellan projektion för tredimensionella objekt jämfört med plana ytor, genom att titta både på mitt projekt och dessa fyra analyser. Nyckelord: animation, visuell musik, projektionsmappning, VJ, datorgrafik Innehållsförteckning Abstract..........................................................................................................................................i -

Remix Magazine, September 1St 2002 TIME BANDITS

Remix Magazine, September 1st 2002 TIME BANDITS Garry Cobain and Brian Dougans — aka Amorphous Androgynous and Future Sound of London — started making magic with sequencers and samplers long before Aphex Twin, The Orb and Orbital were just beginning to dabble in revolutionary sonic experiments. An ultraworld of quicksilver samples, sequenced atmospheres and lushly rolling beats, the duo's early masterpiece Lifeforms (Astralwerks, 1994) suggested, for the first time, an alternate sound world created with computer technology. But just as the world seemed ready for Future Sound of London and accepted their apocalyptic Dead Cities (Astralwerks, 1996) album with open arms, the devious duo disappeared, retreating to reclaim their souls as the media pervaded their psyches. Those were somewhat better times for the pair, before Cobain discovered a certain death that lurked inside his body. “I had developed an arrhythmic heart, massive food and environmental allergies, eczema and stiff joints,” says Cobain from FSOL's Kensal Road recording studio in London. “I realized that my immune system was shot to ribbons by my mercury fillings. Silver is the same thing as mercury. They use the word silver not to tell you that you have the second most toxic substance known to man in your gob. You are talking mass conspiracy shit here.” After having the fillings removed (Dougans followed suit), Cobain took up fasting, meditation and enema cleansing; slowly, year after year, his health returned. But even before Cobain's illness sidelined FSOL, Cobain and Dougans were already tiring of the scene, its influx of ambient compilations and growing corporate interference. -

Alwakeel IDM As A

IDM as a “Minor” Literature: The Treatment of Cultural and Musical Norms by “Intelligent Dance Music” RAMZY ALWAKEEL UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS (UK) Abstract This piece opens with a consideration of the etymology and application of the term “IDM”, before examining the treatment of normative standards by the work associated therewith. Three areas in particular will be focused upon: identity, tradition, and morphology. The discussion will be illuminated by three case studies, the first of which will consider Warp Records’ relationship to narrative; the two remaining will explore the work of Autechre and Aphex Twin with some reference to the areas outlined above. The writing of Deleuze and Guattari will inform the ideas presented, with particular focus being made upon the notions of “minority”, “deterritorialisation”, and “continuous variation”. Based upon the interaction of the wider IDM “text” with existing “constants”, and its treatment of itself, the present work will conclude with the suggestion that IDM be read as a “minor” literature. Keywords IDM, Deleuze, minority, genre, morphology, subjectivity, Autechre, Aphex Twin, Warp Can you really kiss the sky with your tongue in cheek? Simon Reynolds (1999: 193) Why have we kept our own names? Out of habit, purely out of habit. […] Also be- cause it’s nice to talk like everybody else, to say the sun rises, when everybody knows it’s only a matter of speaking. To reach, not the point where one no longer says I, but the point where it is no longer of any importance whether one says I. Deleuze and Guattari (2004: 3-4) Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 1-21 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.01 2 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 Introduction Etymologically, an attempt to determine what “IDM” actually signifies is problematic. -

Power to the People: British Music Videos 1966 - 2016

Power To The People: British Music Videos 1966 - 2016 200 landmark music videos TRL314A_BKLT_R2018.indd 1 17/01/2018 12:46 Disc 1 contains Performance Videos - a genre which has its roots in mid-1960s films such Power To The People: as A Hard Day’s Night (1964). The core deceit of the performance video is that the band British Music Videos 1966 - 2016 do not perform the track live for filming but mimic performance by singing and playing their instruments in synch to audio playback of the track. Some bands and directors Introductory Essay by the curator Professor Emily Caston have rebelled against this deception to create genuine live performance videos such as Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ (1980). There are precedents for the styles used in pre-1966 video jukebox and other short film clips. Directors who excelled in the performance genre often came from a music or record company background, or came This is a collection of some of the most important and influential music videos made in to video directing through album design. Britain since 1966. It’s the result of a three-year research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and run in collaboration with the British Film Institute and From the 1980s onwards video directors fashioned more and more original locations the British Library. The videos were carefully selected by a panel of over one hundred and devices for those artists who were willing to experiment with the performance directors, producers, cinematographers, editors, choreographers, colourists and video genre: Tim Pope & The Cure’s ‘Close To Me’ (1985), Sophie Muller & Blur’s ‘Song 2’ commissioners. -

FSOL and the Poisonous Teeth

DJ Mixed Magazine, October 1st 2002 FSOL and the Poisonous Teeth 10.01.2002 He's Lost The Plot: FSOL And The Case Of The Poisonous Teeth. By Kieran Wyatt The Future Sound of London had the entire UK (and everyone else who was listening to electronic music back then) up on its ears in part one of the 90s. 'Papua New Guinea' and 'Cascades' from Accelerator (1992)? Lifeforms (1994), Dead Cities (1996)? c'mon! But then Garry Cobain, nursing a few extreme maladies, disappeared into the world with only a backpack. How out of touch did he get? FSOL's second half, Brian Dougans, could only track him through his credit card statements. Now he's back with The Isness (hypnotic): Interviewer: What was wrong with you? Garry Cobain: You reach this extreme place where the fucking radio plugger or record buyer is saying they don't like the single or the remix. Fuck that. Interviewer: But I thought you had something physical wrong with you. Garry Cobain: Yeah, poisonous mercury fillings in my teeth. Interviewer: And you ended up in Los Angeles?! Garry Cobain: It was only when I arrived that I realized LA was Hollywood. It was really quite naïve of me. I just hadn't thought about it. Interviewer: And now your music's all Hollywood... Garry Cobain: Music should be overblown and ostentatious and have vision. But we don't make music by committee, like they make Hollywood films. Interviewer: In other words you're an obsessive... Garry Cobain: Oh yeah for sure. I've been sleeping on the floor of my studio on an inflatable bed. -

Moan-Ica to Be a Big Hit!

Daily Star July 1992 Linda Duff’s Rave MOAN-ICA TO BE A BIG HIT! Rave Exclusive THE world-famous grunt of tennis star Monica Seles has been sneakily recorded for a rave disc which could be the surprise nightlife hit of the summer. DJs Garry Cobain and Brian Dougans, of top duo The Future Sound Of London, who last month scored a Top 30 smash with Papua New Guinea, captured it secretly on tape during her final at Wimbledon. Bizarre Now millionaire Monica could net a host of new fans after sneak previews of the record at raves all over Britain. DJ Garry, who smuggled in a tape machine to the Centre Court, is an avid tennis fan and wanted to include Monica’s moan as a bizarre tribute. On the record, grunting sounds kick off the dance track and are then heard at intervals throughout the chorus as the frenetic techno beat turns into a rave anthem. Garry says: “I’m a huge tennis fan and I’m always looking for different and original sounds to sample on my records, so it made perfect sense. “I was worried about being caught, but her grunting was so loud it was easy to get on tape. “I’m really pleased with the outcome – and everyone who’s heard it so far loves it.” Outrageous Garry, 25, turned up at the final in leather jeans and a purple furry jacket in a bid to be noticed by his tennis idol. Excited Now he hopes Monica will be so impressed by the record she will join the band on stage at gig in Britain in the autumn. -

Happy Birthday Hanfapotheke!

r g / Fü ute nt K e u n C d 0 e n 5 k s i o e s r t p e z n t l u o h s c / S unabhängig, überparteilich, legal #63 Ausgabe 10/06 Auch wir machen Fehler. Und nicht ge- Der Herbst is' da, und um den Genuss des rade wenige. Die gröbsten Klopper haben Keinen Cocolores über den Anbau auf Coco. Auf Schmauchwerks zu steigern, gibt's auf den wir in dieser Ausgabe zum Eckthema Seite fünf beschreibt MaxAir was zu tun ist, um Seiten acht und neun wieder ein paar gemacht, damit es nicht heisst, wir lästern auch auf Coco Medium erfolgreich zu gärtnern. musikalische Empfehlungen vom rastlosen E immer nur über andere. 5 8 Roly. news s. 02 guerilla growing s. 04 wirtschaft s. 07 cool-tour s. 08 fun+action s. 10 www.hanfjournal.de Bündnis Hanfparade HappyHappy BirthdayBirthday Hanfapotheke!Hanfapotheke! vor dem Aus? Michael Knodt Am Vorabend der diesjährigen Hanfparade sah alles so schön aus. Patientenprojekt wird ein Jahr alt Michael Knodt Im Gegensatz zum Vorjahr gab es eine genehmigte (wie sich später herausstellte auch gut besuchte) Abschlussveranstaltung mit reichlich Das Verbot der medizinischen Hanfanwendung bringt immer wieder kreative Menschen dazu, die Missstände auf eigene Live-Musik. Faust zu bekämpfen. So startete vor einem Jahr die Hanfapotheke im Internet (www.hanfapotheke.org), deren Ziel es Die Berliner Behörden hatten bis dato keinerlei Einwände gegen ist, Schwerkranke (anonym) mit Cannabis zu versorgen. Ihr erklärtes politisches Ziel ist es, sich selbst irgendwann die Ausstellung von über 10.000 Nutzhanf-Pflanzen angemeldet, überflüssig zu machen; nach der dazu notwendigen Gesetzesänderung sieht es aber derzeit nicht aus. -

London Calling!

Melody Maker July 25 1992 LONDON CALLING! THE FUTURE SOUND OF LONDON have just released an album called “Accelerator” that establishes them as the most awesome and innovative electronic dance band operating anywhere. DAVE SIMPSON gets plugged in. “A LOT OF PEOPLE HAVE SAID THE NAME IS COCKY,” begins Garry Cobain of The Future Sound Of London, “which it is! But, in a way, calling ourselves that is a constant challenge to ourselves. The name does engender this amazing quality control. Unless we come up with the goods every time, we’re gonna get slagged. We know that, and we’ve laid ourselves open with that name. But it’s the only way our music can go forward. “We don’t want The Future Sound Of London to be a functional dance band,” he continues. “We see ourselves going completely outside that area. We want to push dance music beyond its boundaries, but push everybody outside dance music as well! We’re not limiting our music or our appeal to the dance music scene. We’re thinking much bigger than that.” “Actually,” confides his colleague, Brian Dougans, “that’s why there may not be another Future Sound Of London record for six months. Or there might never be another Future Sound Of London record! If we can’t keep making music that’s different or innovative, then we won’t release anything!” BRIAN Dougans and Garry Cobain are currently being talked about as the most innovative and experimental dance and electronic-based unit operating anywhere. When their awesome, genre-busting classic, “Papua New Guinea”, stormed the Top 20 earlier this year, a new musical term was born. -

Garry Cobain Unleash Your Creativity

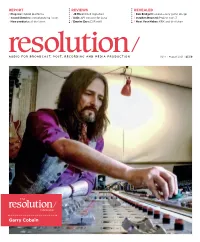

REPORT REVIEWS REVEALED / Plug-ins: Hybrid platforms / JZ Mics: BB29 Signature / Rob Bridgett: sound-savvy game design / Sound libraries: crowdsourcing issues / UAD: API Console for Luna / Stephen Baysted: Project Cars 3 / New products: all the latest / Empire Ears: ESR mkII / Meet Your Maker: KRK and the future V21.4 | August 2021 | £5.50 The Interview Garry Cobain Unleash your creativity Introducing GLM 4.1 loudspeaker manager software For 15 years, GLM software has worked with our Smart Active Monitors to minimise the unwanted acoustic influences of your room and help your mixes sound great, everywhere. Now, GLM 4.1 includes the next generation AutoCal 2 calibration algorithm and a host of new features – delivering a much faster calibration time and an even more precise frequency response. So, wherever you choose to work, GLM 4.1 will unleash your creativity, and help you produce mixes that translate consistently to other rooms and playback systems. And with GLM 4.1, both your monitoring system and your listening skills have room to develop and grow naturally too. Find out more at www.genelec.com/glm / Contents 20 V21.4 | August 2021 News & Analysis 5 Leader 6 News 12 New Products Featuring API, SSL, Cedar, Heritage Audio, KRK and more Columns 14 Crosstalk Rob Speight looks at problems with crowdsourced sound libraries, their metadata, and the benefits of the UCS filename protocol Craft 20 Garry Cobain One half of The Amorphous Androgynous (and previously Garry Cobain Future Sound of London) talks about creating their sprawling psyche-tinged, Floyd-esque LP We Persuade Ourselves We Are Immortal and his adventures in attempting to produce Noel Gallagher 26 Rob Bridgett A leading practitioner in sound design for games, Rob 34 Bridgett is also a pioneering thinker concerning the art and craft of creating best of breed sound, music and dialogue. -

Adam F F Is for Funk

(((ZOOZOOZOOMMM))) ADAM F F IS FOR FUNK Nel ’97 ero un ragazzino che guardava MTV, non avevo hip hop “Kaos” (2001) che ha visto la partecipazione di personaggi del un concetto ben definito di cosa fosse la drum’n’bass, calibro di LL Cool J, Redman, M.O.P., Guru e De La Soul. Purtroppo però sebbene quello fosse l’anno in cui la jungle godeva del invece di imprimere il suo stile in un hip hop ormai statico e sterile Adam massimo splendore, prima che fosse trascinata a forza F si è probabilmente piegato ad esigenze di produzione (“Kaos” è stato nell’abisso techstep con conseguente perdita di interesse da pubblicato su EMI) e il risultato finale è un buon album ma senza parte dei media, che iniziarono a parlare di morte della d’n’b. carattere, troppo simile al mainstream americano, il tocco di uno degli Facendo un confronto con la scena odierna, non si è ancora innovatori della drum’n’bass quasi non si sente. raggiunta quella visibilità che c’era nel ’97, periodo in cui mi Di certo ha riscosso un certo successo che gli ha permesso di aprire rimasero impressi due video che passavano spessissimo un’etichetta, chiamata guarda caso Kaos, la cui prima uscita è stato uno anche alle quattro di pomeriggio: “Brown Paper Bag” di Roni di quegli episodi ‘due pezzi in uno’: dalla fusione di “Your Sound” di J Size e “Music In My Mind” di Adam F. Ovvero, i video dei due Majik e “Metropolis” di Adam F è nato quello spaccapista che tutti personaggi che portarono rispettivamente il jazz e il funk nella conosciamo come “Metrosound”, pubblicato nella primavera del 2002. -

Radio Active August 1994

Radio Active August 1994 Future Sound Of London aim to infiltrate broadcasting and permeate TV and radio, rejecting the traditional roles of studio musicians to fashion themselves into a complete 'broadcast system' with control over every aspect of the audio/visual mix.NIGEL HUMBERSTONE discovers what it's all about. As visionary but reluctant musicians, Future Sound Of London are in the fortunate position (courtesy of Virgin and their publishers, Sony) of being financially supported in the pursuit of their experimental approach to audio/visual manipulation and production. Having caught the public's eye in 1988 with their Stakker Humanoid project, they continued to infiltrate the dance music scene, surfacing in 1992 with the acclaimed crossover-underground hit 'Papua New Guinea'. Submerging once again, they worked under a proliferation of aliases, including SemiReal, Mental Cube, Smart Systems, AST, Indo Tribe, Candese and Yage. But the success of 'Papua New Guinea', which peaked at 22 in the charts, was enough to secure a lucrative deal with Virgin. Thus FSOL's ambitious multi-media plans have slowly been taking shape, with the ultimate aim of operating as an 'audio/visual broadcast system'. In the meantime, under the name Amorphous Androgynous, they released 'Tales of Ephidrina' on their own EBV label in 1993. This was followed by their debut Virgin release, the 30-minute, six-part single 'Cascade'. 'Lifeforms' (the single), featuring the voice of Liz Fraser of the Cocteau Twins, was set for release early this year but subsequently withdrawn due to contractual litigation. Lifeforms (the album) was released in May. Partners Garry Cobain and Brian Dougans initially met in Manchester in 1986, where they both studied Electronics.