Alwakeel IDM As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felix Issue 1131, 1999

issue 1145 University Teachers Approve Strikes The Association of University Teachers voted for other actions less severe than (AUT) has voted to take industrial By Ed Sexton striking. The AUT claims that its mem• action, following a ballot of its mem• bers have not received the pay bers held last month. This will most increases that they are due, with the likely manifest itself as a one day strike General Secretary, David Friesman, later this month, which could affect commenting "vice-chancellors can pay lectures and exams for many students. themselves nearly 7% extra this year, The strike is the result of a failure to but offer their staff only half that reach agreement in the current pay amount, the more we do the less we dispute, which has gone on for several get." months. The debate on whether to go In late March the AUT authorised a ahead with the strike was due to be ballot of its members after rejecting held last Thursday, after Felix went to the 3% pay increase offered by the press. According to the AUT document University and Colleges Employers Asso• "Action for a fair deal" the most likely ciation (UCEA). Determined to pursue date for a 24 hour strike is Tuesday 25 a 10% pay increase, a ballot was May, but the text warns that "the Exec• announced for April, with a possible utive Committee is instructed to con• strike taking place at the end of May. sider calling further strike or strikes in In early April UCEA put forward their the early part of the next academic final offer of 3.5%, which was immedi• year". -

Autechre Confield Mp3, Flac, Wma

Autechre Confield mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Confield Country: UK Released: 2001 Style: Abstract, IDM, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1635 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1308 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 182 Other Formats: AU DXD AC3 MPC MP4 TTA MMF Tracklist 1 VI Scose Poise 6:56 2 Cfern 6:41 3 Pen Expers 7:08 4 Sim Gishel 7:14 5 Parhelic Triangle 6:03 6 Bine 4:41 7 Eidetic Casein 6:12 8 Uviol 8:35 9 Lentic Catachresis 8:30 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warp Records Limited Copyright (c) – Warp Records Limited Published By – Warp Music Published By – Electric And Musical Industries Made By – Universal M & L, UK Credits Mastered By – Frank Arkwright Producer [AE Production] – Brown*, Booth* Notes Published by Warp Music Electric and Musical Industries p and c 2001 Warp Records Limited Made In England Packaging: White tray jewel case with four page booklet. As with some other Autechre releases on Warp, this album was assigned a catalogue number that was significantly ahead of the normal sequence (i.e. WARPCD127 and WARPCD129 weren't released until February and March 2005 respectively). Some copies came with miniature postcards with a sheet a stickers on the front that say 'autechre' in the Confield font. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Sticker): 5 021603 128125 Barcode (Printed): 5021603128125 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1 to 3): WARPCD128 03 5 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1 to 3, Etched In Inner Plastic Hub): MADE IN THE UK BY UNIVERSAL M&L Mastering SID Code -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Drone Records Mailorder-Newsflash MARCH / APRIL 2008

Drone Records Mailorder-Newsflash MARCH / APRIL 2008 Dear Droners & Lovers of thee UN-LIMITED music! Here are our new mailorder-entries for March & April 2008, the second "Newsflash" this year! So many exciting new items, for example mentioning only the great MUZYKA VOLN drone-compilation of russian artists, the amazing 4xLP COIL box, a new LP by our beloved obscure-philosophist KALLABRIS, deep meditation-drones by finlands finest HALO MANASH, finally some new releases by URE THRALL, and the four new Drone EPs on our own label are now out too!! Usually you find in our listing URLs of labels or artists where its often possible to listen to extracts of the releases online. LABEL-NEWS: We are happy to take pre-orders for: OÖPHOI - Potala 10" VINYL Substantia Innominata SUB-07 Two long tracks of transcendental drones by the italian deep-ambient master, the first EVER OÖPHOI-vinyl!! "Dedicated to His Holiness The Dalai Lama and to Tibet's struggle for freedom." Out in a few weeks! Soon after that we have big plans for the 10"-series with releases by OLHON ("Lucifugus"), HUM ("The Spectral Ship"), and VOICE OF EYE, so watch out!!! As always, pre-orders & reservations are possible. You also may ask for any new release from the more "experimental" world that is not listed here, we are probably able to get it for you. About 80% of the titles listed are in stock, others are backorderable quickly. The FULL mailorder-backprogramme is viewable (with search- & orderfunction) on our website www.dronerecords.de. Please send your orders & all communication to: [email protected] PLEASE always mention all prices to make our work on your orders easier & faster and to avoid delays, thanks a lot ! (most of the brandnew titles here are not yet listed in our database on the website, but will be soon, so best to order from this list in reply) BUILD DREAMACHINES THAT HELP US TO WAKE UP! with best drones & dark blessings from BarakaH 1 AARDVARK - Born CD-R Final Muzik FMSS06 2007 lim. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

Weaving Genres, and Roughing up Beats: New Album Review

Weaving Genres, And Roughing Up Beats: New Album Review Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world Is it just me, or was Record Store Day 2017 a tiny bit crap? The last time I was surrounded by that amount of middle-aged, balding men, reeking of sweat, I had walked into a strip-club by mistake. So, rather than relive the horrors of that day, I will dispense with the waffle and dive straight into the reviews. By JOHN BITTLES The electronic musings of Darren Jordan Cunningham’s Actress project have long been a favourite of those who enjoy a bit of cerebral resonance with their beats. While 2014’s Ghettoville disappointed, there was more than enough goodwill left over from the dusty grooves of his R.I.P. album and his excellent DJ Kicks mix to ensure that expectations for a new LP were suitably high Thankfully the futuristic funk and controlled passion of AZD doesn’t let us down! Out now on the always reliable Ninja Tune label the album is a dense listening experience which makes the ideal soundtrack for lonely dance floors and fevered heads. After the short intro of Nimbus, Untitled 7 gets us off to a stunning start with its deep, steady groove. From here Fantasynth’s shuffling beats and solitary melody line recall the twisted genius of Howie B and Dancing In The Smoke deconstructs the ghost of Chicago house and takes it to a gloriously darkened place. Meanwhile Faure In Chrome and There’s An Angel In The Shower’s disquieting ambiance are so good you could wallow in them for days. -

Roedelius Bio Engl

ROEDELIUS: JARDIN AU FOU CD and Vinyl Release date: March 27th 2009 Cat No BB23 CD 927892/LP 927891 The essentials: ► Hans-Joachim Roedelius: born 1934; first record release in 1969 with Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Konrad Schnitzler), and active ever since as a solo artist and in various collaborations (amongst others with Moebius/Cluster, Moebius and Michael Rother/Harmonia, as well as with Brian Eno). One of the most prolific musicians of the German avant-garde and a key figure in the birth of Krautrock, synthesizer pop and ambient music. ► Jardin au Fou was first released on the French EGG label in 1979 ► produced by Peter Baumann (Tangerine Dream) ► liner notes by Asmus Tietchens ► CD features six bonus tracks: three remixes, three new tracks One of the most remarkable albums of the so-called Krautrock scene has to be Jardin au Fou by Hans-Joachim Roedelius (Cluster, Harmonia), issued in 1979. All the more noteworthy as it bore no resemblance whatsoever to what was expected of avant-garde electronica and displayed none of the typical Krautrock characteristics. Rhythm machine, sequencer and abstract sounds are conspicuous by their absence. Indeed, listeners were stunned by one of the most beautiful, charming, ethereal and peaceful albums in the history of German rock music. It was produced by Peter Baumann at his own Paragon Studios in 1978, a year after he left Tangerine Dream to concentrate on a solo career and production work. At the time, he was charged by the French label EGG with delivering three productions from the German electro/avant- garde/Krautrock cosmos. -

Generative Rhythmic Models

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarly Materials And Research @ Georgia Tech GENERATIVE RHYTHMIC MODELS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Alex Rae In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Music Technology in the Department of Music Georgia Institute of Technology May 2009 GENERATIVE RHYTHMIC MODELS Approved by: Professor Parag Chordia, Advisor Department of Music Georgia Institute of Technology Professor Jason Freeman Department of Music Georgia Institute of Technology Professor Gil Weinberg Department of Music Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES . v LIST OF FIGURES . vi SUMMARY . viii I INTRODUCTION . 1 1.1 Background . 6 1.1.1 Improvising Machines . 6 1.1.2 Theories of Creativity . 8 1.1.3 Creativity and Style Modeling . 10 1.1.4 Graphical Models . 10 1.1.5 Music Information Retrieval . 11 II QAIDA MODELING . 14 2.1 Introduction to Tabla . 15 2.1.1 Theka . 19 2.2 Introduction to Qaida . 20 2.2.1 Variations . 21 2.2.2 Tihai . 22 2.3 Why Qaida? . 22 2.4 Methods . 24 2.4.1 Symbolic Representation . 29 2.4.2 Variation Generation . 31 2.4.3 Variation Selection . 35 2.4.4 Macroscopic Structure . 38 2.4.5 Tihai . 38 2.4.6 Audio Output . 39 2.5 Evaluation . 40 iii III LAYER BASED MODELING . 47 3.1 Introduction to Layer-based Electronica . 49 3.2 Methods . 51 3.2.1 Source Separation . 55 3.2.2 Partitioning . -

Artificial Intelligence, Ovvero Suonare Il Corpo Della Macchina O Farsi Suonare? La Costruzione Dell’Identità Audiovisiva Della Warp Records

Philomusica on-line 13/2 (2014) Artificial Intelligence, ovvero suonare il corpo della macchina o farsi suonare? La costruzione dell’identità audiovisiva della Warp Records Alessandro Bratus Dipartimento di Musicologia e Beni Culturali Università di Pavia [email protected] § A partire dai tardi anni Ottanta la § Starting from the late 1980s Warp Records di Sheffield (e in seguito Sheffield (then London) based Warp Londra) ha avuto un ruolo propulsivo Records pushed forward the extent nel mutamento della musica elettronica and scope of electronic dance music popular come genere di musica che well beyond its exclusive focus on fun non si limita all’accompagna-mento del and physical enjoinment. One of the ballo e delle occasioni sociali a esso key factors in the success of the label correlate. Uno dei fattori chiave nel was the creative use of the artistic successo dell’etichetta è stato l’uso possibilities provided by technology, creativo delle possibilità artistiche which fostered the birth of a di- offerte dalla tecnologia, favorendo la stinctive audiovisual identity. In this formazione di un’identità ben ca- respect a crucial role was played by ratterizzata, in primo luogo dal punto the increasing blurred boundaries di vista audiovisivo. Sotto questo profilo between video and audio data, su- un ruolo fondamentale ha giocato la bjected to shared processes of digital possibilità di transcodifica tra dati transformation, transcoding, elabora- audio e video nell’era digitale, poten- tion and manipulation. zialmente soggetti agli stessi processi di Although Warp Records repeatedly trasformazione, elaborazione e mani- resisted the attempts to frame its polazione. artistic project within predictable Nonostante la Warp Records abbia lines, its production –especially mu- ripetutamente resistito a ogni tentativo sic videos and compilations– suggests di inquadrare il proprio progetto arti- the retrospective construction of a stico entro coordinate prevedibili, i suoi consistent imagery. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

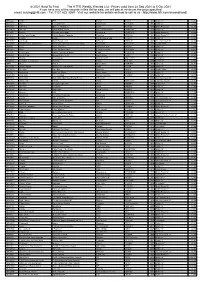

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

Autechre Envane Mp3, Flac, Wma

Autechre Envane mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Envane Country: UK Released: 1997 Style: Abstract, IDM MP3 version RAR size: 1213 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1665 mb WMA version RAR size: 1291 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 410 Other Formats: MMF XM ADX AHX APE MP1 FLAC Tracklist 1 Goz Quarter 9:43 2 Latent Quarter 7:37 3 Laughing Quarter 7:05 4 Draun Quarter 10:50 Companies, etc. Published By – Warp Music Published By – EMI Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warp Records Limited Copyright (c) – Warp Records Limited Credits Design – The Designers Republic Producer – Ae* Written-By – Brown*, Booth* Notes Warp Music EMI Music. (P) 1997 Warp Records Ltd (C) 1997 Warp Records Ltd. Made In England. Released in a standard jewel case with clear tray and 4-page booklet. "Goz Quarter" samples a lyric from Dr. Octagon's "No Awareness". Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Printed): 5021603089020 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1): 83191 WAP89CD Matrix / Runout (Variant 2): 95637 WAP89CD 1:1:1 Matrix / Runout (Variant 3): 83191 WAP89CD 1:1:3: Matrix / Runout (Variant 4): WAP89CD Matrix / Runout (Variant 5): 83191 WAP89CD 1:1:4 Matrix / Runout (Variant 6): 83191 WAP89CD I:1:8 Mastering SID Code (Variant 1, 3, 5, 6): IFPI L042 Mastering SID Code (Variant 2): IFPI L041 Mastering SID Code (Variant 4): IFPI LR61 Mould SID Code (Variant 1, 5): none Mould SID Code (Variant 2): IFPI 7306 Mould SID Code (Variant 3): IFPI 7305 Mould SID Code (Variant 4): IFPI RZ08 Mould SID Code (Variant 6): IFPI 7303 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year WAP 89 CDP Autechre Envane (CD, EP, Promo) Warp Records WAP 89 CDP UK 1997 WAP 89 Autechre Envane (12") Warp Records WAP 89 UK 1997 WAP89 Autechre Envane (12", W/Lbl, Sti) Warp Records WAP89 UK 1997 WAP 89X Autechre Envane (12") Warp Records WAP 89X UK 1997 WAP 89CD Autechre Envane (CD, EP, RP) Warp Records WAP 89CD UK Unknown Comments about Envane - Autechre Quendant One of my faves in the Autechre catalog.