Josiah White and the Lehigh Canal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pennsylvania June, 2004

A Bicentennial Inventory of America's Historic Canal Resources Published by the American Canal Society, 117 Main St., Freemansburg, PA 18017 DRAFT Pennsylvania June, 2004 Map by William H. Shank Amazing Pennsylvania Canals American Canal & Transportation Center PENNSYLVANIA CANALS State Canals Beaver Division Conneaut Division Delaware Division Eastern Division Juniata Division North Branch Division Shenango Division Susquehanna Division West Branch Division Western Division Bald Eagle & Spring Creek Navigation Codorus Navigation Conestoga Navigation Delaware & Hudson Canal Lehigh Canal Leiper Canal Pennsylvania & Ohio Cana lSandy & Beaver Canal Schuylkill Navigation Susquehanna & Tidewater Canal Union Canal Pine Grove Brasnch & Feeder Wiconisco Canal CONNECTING RAILROADS Allegheny Portage Railroad Delaware & Hudson Gravity Railroad Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad New Portage Railroad Pennsylvania Coal Company Gravity Railroad Philadelphia & Columbia Railroad Switchback Gravity Railroad BIBLIOGRAPHY Archer, Robert F., A History of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, Howell-North Books, Berkeley, CA 1978 ISBN 0- 8310-7113-3 Barber, David G., A Guide to the Lehigh Canal, Lower & Upper Divisions, Appalachian Mountain Club, Delaware Valley Chapter, 1992, 136 pages Barber, David G., A Guide to the Delaware & Hudson Canal, Center for Canal History and Technology, Easton, PA, 2003, 164 pages, ISBN 0-930973-32-1 Bartholomew, Ann and Metz, Lance E., Delaware and Lehigh Canals, Center for Canal History and Technology, Easton, PA, 1989, 158 pages, ISBN 0-930973-09-7 -

ANTHRACITE Downloaded from COAL CANALS and the ROOTS of AMERICAN FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCE, 1820–1860 Envhis.Oxfordjournals.Org

CHRISTOPHER F. JONES a landscape of energy abundance: ANTHRACITE Downloaded from COAL CANALS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCE, 1820–1860 envhis.oxfordjournals.org ABSTRACT Between 1820 and 1860, the construction of a network of coal-carrying canals transformed the society, economy, and environment of the eastern mid- Atlantic. Artificial waterways created a new built environment for the region, an energy landscape in which anthracite coal could be transported cheaply, reliably, at Harvard University Library on October 26, 2010 and in ever-increasing quantities. Flush with fossil fuel energy for the first time, mid-Atlantic residents experimented with new uses of coal in homes, iron forges, steam engines, and factories. Their efforts exceeded practically all expec- tations. Over the course of four decades, shipments of anthracite coal increased exponentially, helping turn a rural and commercial economy into an urban and industrial one. This article examines the development of coal canals in the ante- bellum period to provide new insights into how and why Americans came to adopt fossil fuels, when and where this happened, and the social consequences of these developments. IN THE FIRST DECADES of the nineteenth century, Philadelphians had little use for anthracite coal.1 It was expensive, difficult to light, and considered more trouble than it was worth. When William Turnbull sold a few tons of anthracite to the city’s waterworks in 1806, the coal was tossed into the streets to be used as gravel because it would not ignite.2 In 1820, the delivery © 2010 The Author. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Society for Environmental History and the Forest History Society. -

The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1989 The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal Stuart William Wells University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Wells, Stuart William, "The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal" (1989). Theses (Historic Preservation). 350. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Wells, Stuart William (1989). The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Wells, Stuart William (1989). The Schuylkill Navigation and the Girard Canal. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/350 UNIVERSITY^ PENNSYLVANIA. LIBRARIES THE SCHUYLKILL NAVIGATION AND THE GIRARD CANAL Stuart William -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

James D. Harris, Principal Engineer, and James S. Stevenson, Canal Commissioner

JAMES D. HARRIS, PRINCIPAL ENGINEER, AND JAMES S. STEVENSON, CANAL COMMISSIONER By HUBERTIS M. CUMMINGS T HE career of James Dunlop Harris in connection with the 1building of the Canals of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was not initiated with peculiarly brilliant auspices. It was by Act of February 25, 1826, that the program for effectuation of the State's proposed system of Internal Improve- ments was officially endorsed. Seven weeks later, on April 6, a letter from Joseph McIlvaine, Secretary to the new Board of Canal Commissioners, went forward from Philadelphia, requesting that Mr. Harris "proceed forthwith to Pittsburgh, and take the place of assistant to Nathan S. Roberts."' For his service under that distinguished engineer, who himself had come into the employment of Pennsylvania after a career upon the Erie Canal in New York, he was to have three dollars a day and necessary expenses. 2 Three to four months later, the young surveyor from Bellefonte had run his levels between Pine Creek and the City of Pittsburgh, in conformity to the Board's instructions to his superior, and "con- tinued them over Grant's Hill to Suke's Run for the purposes of ascertaining the propriety of terminating the canal at the Monon- gahela in that direction."' This feat, reported on November 304 bv himself, was clarified by another report of the same date by Nathan S. Roberts. That second engineer recommended a route by the course which his assistant had located: for, "very expensive" and "longer" than other routes as it would be, it "would do less damage to individuals" 5 as it passed "around the southern suburbs,"6 ' Joseph McIlvaine to J. -

Guide-Book of the Lehigh Valley Railroad And

t.tsi> GUIDE-BOOK OF THE LEHIGH VALLEY RAILROAD AND ITS SEVERAL BRANCHES AND CONNECTIONS; WITH AN ACCOUNT, DESCRIPTIVE AND HISTORICAL, OF THE PLACES ALONG THEIR ROUTE; INCLUDING ALSO A HISTORY OF THE COMPANY FROM ITS FIRST ORGANIZA- TION. AND INTERESTING FACTS CONCERNING THE ORIGIN AND GROWTH OF THE COAL AND IRON TRADE IN THE LEHIGH AND WYOMING REGIONS. HANDSOMELY ILLISTEATED FROM RECENT SKETCHES, PREFIXED TO WHICH IS A MAP OF THE ROAD AND ITS CONNECTIONS. PHILADELPHIA: A J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO. 1873. flS^ Cn Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by WILLIAM H. SAYRE, In the OfBce of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, by WILLIAM H. SAYRE, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. RELIABLE CONNECTIONS FREIGHT. QUICK TIME Tlic facilities of the Lehigh Valley Double Track Uailroad LAST HXPRLSS TRAINS, for the prompt dispatch of all kinds iif Merchandise Krciglils are iHU'i|ualed. NEW YORK, Fast PHILADKLlMllA, DOUBLE TRACK SHORT LINE, Frhigi IT Trains BALTIMUKK, WIN n.Ml.V liKTWKKN AND RUNNING TO ANU FROM ALL POINTS IN TlIK New WASHINGTON, York, Mahanoy City, Philadelphia, Wilkes-Marrc, DAILY (Suiidi y» ox.,o,)U)cJ) for Belhlohein, Pittslon, Allcntown, Auburn, .MIdUowii, Maiich CliunU, Rodu-St.T, MAHAIOY,BEAyER MEADOW, HAZLETON &WYOMING I'iiiilra, Glen Onoko, and tlu Buffalo, Mauch Clumk, Ithaca, Switch-back, Niagara Falls, Hazleton, Owego, Catawissa, The Canadas, COAL FIELDS, Catawissa, Auburn, Sunbui^, Dunkirk, Danville, Rochester, Wilkcs-Ban-e, Erie, . Pittston, Oil Regions, AND THROUGH THE .Sunbury, Buffalo, Hazleton, Cleveland, Danville, Toledo, ,\Ni) Al.l, I'OIN-IS IN Till'; Mahanoy City, 1 )etroit. -

Lehigh Canal Recreation Commission July 17, 2018 Elaine L. Chao

Lehigh Canal Recreation Commission July 17, 2018 Elaine L. Chao Secretary of Transportation United States Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE Washington, DC 20590 Re: BUILD 2018: Riverside Drive Multimodal Revitalization Corridor Project Dear Ms. Chao: This letter is to express support for the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission’s request for a 2018 BUILD grant. The grant funding requested is a missing link to fully connect the 165-mile D&L Trail. The project location near the mid-point of this long-distance trail will impact the four townships and three boroughs that the Lehigh Canal Recreation Commission represents via Allentown’s Riverside Drive Multimodal Revitalization Corridor project. We include Parryville, East Penn, Mahoning, and Franklin townships as well as Lehighton, Weissport and Jim Thorpe Boroughs. Riverside Drive is a 3.25 mile multi-municipal commuter corridor, includes a twelve foot bike and walking commuter corridor that is part of the main north-south route of the D&L Trail. This is a collaboration of more than 20 local public, private and non-profit organizations working together. It is a critical commuting link in the 165-mile Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor Trail network and offers an alternative travel option to regional trail systems and job centers. It improves connectivity between rural and urban areas of the Lehigh Valley and eastern Pennsylvania. The project is located along a vacated rail corridor adjacent to a redevelopment project known as The Waterfront, in the City of Allentown. On the large former brownfield, formerly Lehigh Structural Steel, the project will provide a river walk, floating docks to support public access to the river, two public plazas, and a main street through the adjacent site redevelopment. -

Switchback Book.Indd

Switchback Grav ity Railroad Historic Landscape Preservation Planning Study Graduate Program in Historic Preservation School of Design University of Pennsylvania Acknowledgements This study was conducted at the request, and with the support, of the Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, for which Dale Freudenberger served as project manager. The project partners and University of Pennsylvania team would like to thank all those who contributed to the research and analysis and those who provided advice and input. Study Team: Preservation Studio 2007, Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, School of Design, University of Pennsylvania Alex Bevk, Jenna Cellini, Caroline Cheong, Nicole Collum, Mark Donofrio, Sean Fagan, Marco Federico, Kimberly Forman, Anita Franchetti, Catherine Keller, Maureen McDougall, Sara McLaughlin, Suzanne Segur, Imogen Wirth-Granlund, Emily Wolf, Randall Mason (Associate Professor), Ashley J. Hahn (Teaching Assistant), Erica C. Avrami (Critic) Partners: Dale Freudenberger, Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor Joseph DiBello, National Park Service; Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance (RTCA) John Drury, Switchback Gravity Railroad Foundation Contributors and Advisors: Citizens from the towns of Jim Thorpe and Summit Hill Mauch Chunk Historical Society Toni Artuso, Carbon County Office of Economic Development Summit Hill Historical Society Phyllis Bolton, Carbon County Planning Office & Redevelopment Authority Dennis DeMara, PA DCNR Michael Heery, Carbon County Chamber of Commerce Dan Hugos, Jim -

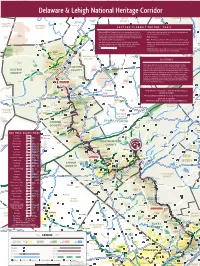

The Corridorland Can 209 Be Found 11 Port Miles Open590 and 84Publicly Accessible

6 191 97 55 BRADFORD COUNTY 29 6 Delaware6 & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor652 42 81 Lackawanna Wayne County Park NEW YORK State Park Carbondale 6 State Game 6 WAYNE Land 316 SULLIVAN COUNTY State Game Land 307 Rabbit Hollow COUNTY (Wildlife Sanctuary) 92 191 97 SULLIVAN Archbald Pothole Clarks Summit Varden COUNTY WYOMING State Park Conservation Archbald AreaFAS T FAC T S ABOU T THE D&L TRAIL 6 laware COUNTY EXIT 194 De Ri ve 6 r 42 What StateYou Game Will Find: Hundreds of sites on the National Register of Historic Surface: While surfaces may vary by region, the trail is primarily eight feet Land 300 Places; twenty-four stateState game Game lands; fourteen national historic landmarks; six Statewide Game and topped with crushed limestone. 6 State Game ORANGE State Game 81 Land 310 Lake Land 183 Land 57 national recreation trails; thirteen state parks; three state historical sites; three Land 116 97 State Game 476 Wallenpaupack Grade: Mostly level. Upper Delaware Land 66 Lackawanna national natural landmarks; two Pennsylvania scenic rivers, one National Scenic COUNTY River Management Area Heritage River; and a National348 Historic Landmark District. 590 Rules: No motorized vehicles. No alcohol. Local rules and regulations apply.Buckhorn Trail State Game 309 (proposed) 380 6 Natural Area 435 Open Trail: The D&L Trail is a work in progress with approximately507 140 Signage: Waysides depicting the unique history of the CorridorLand can 209 be found 11 Port miles open590 and 84publicly accessible. When complete, the D&L Trail and Spurs along402 the route. Directional signs and mile markers are being installed on an 92 Scranton 191 Jervis Back will provide 165 miles of multi-use trail. -

Lehigh Canals, Historical Significance (Continued)

CANAL STATUS ACS HAER STATE/PROVINCE LENGTH LIFT LOCKS DATES IN USE CANAL SLACKWATER TOTAL No./SIZE COUNTIES: LOCATION (Endpoints of Canal): 1 2 TOPOGRAPHIC MAPS: 3 4 ENLARGEMENTS HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE: PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: American Canal Society Index NAMES & ADDRESSES OF GROUPS CONCERNED WITH CANAL'S PRESERVATION/RESTORATION: BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY: UNPUBLISHED RECORDS, PHOTOS, DRAWINGS (CEHR, HAER, HABS. Local or Regional Historical Societies, Libraries, etc.): EXISTING OR RECOMMENDED LANDMARK STATUS (CEHR, National Register, ETC.): Investigation made by: Date: Address: Use additional pages for added information Lehigh Canals, Historical Significance (continued) Josiah White’s final achievement, to tie his entire navigation and transportation system together from east to west, was the “Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad” completed in 1841, which carried freight over the mountains 25 miles from White Haven on the Lehigh to Wilkes-Barre on the Susquehanna. To lift the loaded cars out of the Wyoming Valley at the north end of the route, he used a series of three inclined planes, known as the “Ashley Planes,” run by powerful stationary engines similar in design to those on the Allegheny Portage Railroad. These planes were said to have the highest lift of any in the world. The rail line also included a 1,800-foot tunnel north of White Haven. Disaster struck Josiah White’s enterprises in 1841 when a tremendous flood rolled down the Lehigh Valley, with great loss of life, destroying most of the Lehigh Navigation System, portions of his coal and iron works, and virtually all of the beautifully constructed locks of the Lehigh Valley Canal. Such a catastrophe would have ruined a lesser man, but Josiah White, with fierce determination, within four months rebuilt enough of his navigation system to get back into operation, at least to Philadelphia, and shortly thereafter, restored most of his canal system to its original condition. -

D&R Canal.Qxd

THE DELAWARE & RARITAN CANAL: 175 YEARS AND COUNTING hat’s 66 miles long, 75 feet expansion that followed it, the 1860s The business of the canal was to serve wide, and 175 years old? and 1870s were the most profitable business. All along the route, canalboats WYou’ve probably guessed years for the waterway. In fact, in 1866, delivered Pennsylvania anthracite coal to that it’s the Delaware and Raritan Canal, a record 2,990,000 tons were shipped factories, homes, and coal yards in New the best kept secret in Central New through the waterway—more tonnage Jersey, New York harbor, and points Jersey. than was carried in any single year on north and south. They brought farm This long, narrow, state park is a the much longer and more famous Erie products to market; carried store-bought peaceful haven for the residents of this, Canal. goods to residents in the interior; the most densely populated state in the Anthracite coal was the chief cargo delivered raw materials to factories; and nation. The D&R offers miles of transported on the D&R. It was distributed finished products to outlets wooded towpaths and gently flowing shipped from the coalfields of throughout the region. Businesses along water where visitors can walk, jog, bike, northeastern Pennsylvania to Easton, via the canal included food packing fish, take photographs, birdwatch, ride the Lehigh Canal, or to Philadelphia, via companies, rubber reclaiming plants, horses, cross-country ski, canoe, kayak, the Schuylkill Canal. From Easton, distilleries, coal yards, quarries, lumber or just sit and enjoy the quiet. -

The Upper Grand Section of the Lehigh Navigation Is Built from Mauch Chunk to White Haven. with 20 Dams and 29 Locks, This Water

The Delaware Canal The Upper Grand The American Slate quarrying be- The peak year of The Great Flood of The Bethlehem Iron Fire at the Avondale 1834 and Morris Canal 1838 section of the Lehigh 1840 Industrial Revolution 1848 gins rapid growth 1855 anthracite coal 1862 June 3-5, the Lehigh 1863 Company begins 1869 Mine near Plymouth, connect with the Lehigh Navigation Navigation is built from Mauch begins with the first large-scale with the founding of Bangor by transport on the Lehigh and River region’s worst-ever natural production of iron railroad rails at Luzerne County, kills 110 miners. (completed in 1829) at Easton. The Chunk to White Haven. With 20 production of iron using anthracite Welsh immigrant Robert Jones. Delaware canals; 1.3 million tons disaster, destroys the Upper Grand its South Bethlehem location. In response, Pennsylvania three-canal system carried dams and 29 locks, this coal and local iron ore, at the The “Slate Belt” extends through of anthracite are delivered from section, the upper Lehigh lumber- Bethlehem Iron Company was the enacts the first mine safety laws anthracite to the Philadelphia and waterway overcame a difference Lehigh Crane Iron Works in what central Northampton County from northern mines. The Lehigh Valley ing industry, and much of the predecessor of the Bethlehem in the United States, but the di- New York markets. in elevation of more than 600 feet. is now Catasauqua. Slatington to Bangor. Railroad opens late in the year. Lehigh Canal. Steel Company. saster spurs mine union activity..