The Inherent Conflict of Interest in Police-Prosecutor Relationships & How Immunity Lets Them 'Get Away with Murder', 54 Idaho L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment with Unadjudicated Perjury: Deadly Than the Witnesses Ever Had Said!”2 Weapon Or Imaginary Beast?

Litigation News November 2016 Volume XVII, Number IX December 2016 Few Perjurers Are Prosecuted Impeachment with Although lying under oath is endemic, perjury is Unadjudicated Perjury: rarely prosecuted. When it is, the defendant is usu- ally a politician. The prosecution of Alger Hiss was Deadly Weapon or probably the most famous political perjury prosecu- tion ever in the United States. It made a young anti- Imaginary Beast? communist California Congressman named Richard Nixon a household name.3 The recent perjury by Robert E. Scully, Jr. conviction of Kathleen Kane, the Attorney General Stites & Harbison, PLLC of Pennsylvania, for lying about her role in leaking grand jury testimony to embarrass a political oppo- Impeaching a witness at trial with his prior nent is a modern case in point.4 More memorable untruthfulness under oath is the epitome of cross for those of us of a certain age, President Bill Clinton examination. When you do it, the day is glorious. testified falsely under oath in a judicially supervised When someone does it to your witness, your month deposition in a federal civil case that he did not have is ruined. Yet, this impeachment method is seldom sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. He was not successfully employed. It is very like Lewis Carroll’s prosecuted for perjury despite being impeached by imaginary Snark, which when hunted could not be the House of Representatives, fined $900,000.00 for 1 caught: “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.” civil contempt by the presiding federal judge, and Only the unadjudicated perjurer can catch himself having had his Arkansas law license suspended for out on cross because “extrinsic evidence” of the act is five years for the falsehood.5 Absent some such prohibited. -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

Police Perjury: a Factorial Survey

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey Author(s): Michael Oliver Foley Document No.: 181241 Date Received: 04/14/2000 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0032 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL-FINAL TO NCJRS Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey h4ichael Oliver Foley A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The City University of New York. 2000 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. I... I... , ii 02000 Michael Oliver Foley All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Promotion and Protection of the Human Rights and Fundamental

Written Submission prepared by the International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara University School of Law for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Call for Input on the Promotion and protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Africans and people of African descent against excessive use of force and other human rights violations by law enforcement officers pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 43/1 International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara Law 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, CA 95053-0424 U.S.A. Tel: +1 (408) 554-4770 [email protected] http://law.scu.edu/ihrc/ Diann Jayakoddy, Student Maxwell Nelson, Student Sukhvir Kaur, Student Prof. Francisco J. Rivera Juaristi, Director December 4, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 3 II. IN A FEDERALIST SYSTEM, STATES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS MUST EXERCISE THEIR AUTHORITY TO REFORM LAWS ON POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY AND ON RESTRICTING THE USE OF FORCE BY POLICE OFFICERS 4 A.Constitutional standards on the use of force by police officers 5 B.Federal law governing police accountability 6 C.State police power 7 D.Recommendations 9 III. STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS MUST LIMIT THE ROLE OF POLICE UNIONS IN OBSTRUCTING EFFORTS TO HOLD POLICE OFFICERS ACCOUNTABLE IN THE UNITED STATES 9 A.Police union contracts limit accountability and create investigatory and other hurdles 10 1.Police unions can impede change 11 2.Police unions often reinforce a culture of impunity 12 B.Recommendations 14 IV. INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS REGARDING NON-DISCRIMINATION AND THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS TO LIFE, HEALTH, AND SECURITY REQUIRE DIVESTMENT OF POLICE DEPARTMENT FUNDING AND REINVESTMENT IN COMMUNITIES AND SERVICES IN THE UNITED STATES 14 A.“Defunding the Police” - a Movement Calling for the Divestment of Police Department Funding in the United States and Reinvestment in Communities 15 B.Recommendations 18 2 I. -

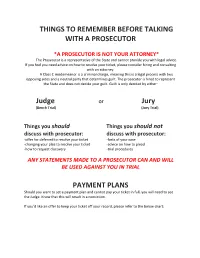

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GEORGE RAHSAAN BROOKS, Petitioner, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Respondent On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI George Rahsaan Brooks, pro se State Correction Institution Coal Township 1 Kelley Drive Coal Township, Pennsylvania 17866-1021 Identification Number: AP-4884 QUESTIONS PRESENTED WHETHER THE UNITED STATES HAS A SUBSTANTIAL INTEREST IN PREVENTING THE RISK OF INJUSTICE TO DEFENDANT AND AN IN- TEREST IN THE PUBLIC'S CONFIDENCE IN THE JUDICIAL PROCESS NOT BEING UNDERMINED? WHETHER THE STATE COURT'S DECISION CONCERNING BRADY LAW WAS AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF CLEARLY ESTABLISHED FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? WHETHER THE STATE COURTS ENTERED A DECISION IN CONFLICT WITH ITS RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURES, DECISIONAL LAW AND CONSTITU- TION ON THE SAME IMPORTANT MATTER AS WELL AS DECIDED AN IMPOR- TANT FEDERAL QUESTION ON NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IN A WAY THAT CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT AND DEPARTED FROM THE AC- CEPTED AND USUAL COURSE OF JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS AND FEDERAL LAW? a. WHETHER THE SUPERIOR'S COURT'S DECISION THAT CHARGING IN- STRUMENT IS NOT NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IS AN UNREASONABLE DETERMINATION OF FACTS IN LIGHT OF THE EVIDENCE PRESENTED TO THE STATE COURT AND AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? DID THE STATE COURT WILLFULLY FAIL TO DECIDE AN IMPORTANT QUESTION OF FEDERAL LAW AND THE CONSTITUTION ON FRAUD ON THE COURT WHICH HAS BEEN SETTLED BY FEDERAL LAW AND BY THIS COURT? I APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Commonwealth v. -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships. -

The Prosecutor, the Term “Prosecutorial Miscon- Would Clearly Fall Within a Layperson’S Definition of Prose- Duct” Unfairly Stigmatizes That Prosecutor

The P ROSECUTOR Measuring Prosecutorial Actions An Analysis of Misconduct versus Error B Y S HAWN E. MINIHAN Rampant Prosecutorial Misconduct The New York Times, Jan. 4, 2014 The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, And The System That Protects Them The Huffington Post, Aug. 5, 2013 Misconduct by Prosecutors, Once Again The New York Times, Aug. 13, 2012 22 O CTOBER / NOVEMBER / DECEMBER / 2014 P ROSECUTORIAL MISCONDUCT has become nation- in cases where such a perception is entirely unwarranted… .”11 al news. To a layperson, the term “prosecutorial miscon- The danger inherent in the court’s overbroad use of the duct” expresses “intentional wrongdoing,” or a “deliberate term “prosecutorial misconduct” is twofold. First, in cases violation of a law or standard” by a prosecutor.1 where there is an innocent mistake or poor judgment on The newspaper articles cited at left describe acts that the part of the prosecutor, the term “prosecutorial miscon- would clearly fall within a layperson’s definition of prose- duct” unfairly stigmatizes that prosecutor. A layperson may cutorial misconduct. For example, the article “Rampant assume that the prosecutor intentionally committed a Prosecutorial Misconduct” discusses United States v. Olsen, wrongdoing or deliberately violated a law or ethical stan- where federal prosecutors withheld a report that revealed dard. sloppy work on the part of the government’s forensic sci- In those cases where the prosecutor has, in fact, commit- entists, resulting in wrongful convictions.2, 3 The article ted misconduct, the term “prosecutorial misconduct” may “The Untouchables: America’s Misbehaving Prosecutors, not impose a harsh enough degree of stigmatization. -

The Role of the Prosecutor: Serving the Interests of All the People

V INE.2PPR 03/14/01 10:33 AM THE ROLE OF THE PROSECUTOR: SERVING THE INTERESTS OF ALL THE PEOPLE Alan Vinegrad* The legal profession’s conception of public interest work has tradi- tionally focused on the work of pro bono or civil liberties-based organi- zations, such as the American Civil Liberties Union and its local chapters, a variety of legal defense funds, the Legal Aid Society, and other similar organizations. Certain law schools provide financial incentives and insti- tutional support designed to actively encourage their students to pursue job opportunities with these groups. Many students—the author in- cluded—can easily spend three years at a law school and not have any notion that public interest work also includes the job of being an Assistant District Attorney (local prosecutor), an Assistant Attorney General (state prosecutor), or an Assistant United States Attorney (federal prosecutor). Many others, aware of the general role of the prosecutor in our legal system, nevertheless have been steeped in publicity in recent years about the rather unique and increasingly politicized work of our most prominent prosecutors—the special prosecutors appointed under the now defunct Independent Counsel statute.1 From this publicity, one can easily draw incomplete, if not unfair, judgments about what it means to be a prose- cutor in our society. It did not occur to me until well into my legal career that my own notion of public interest work was under-inclusive in this one significant respect: it did not include the work of the tens of thousands of federal, state, and local prosecutors across the country who lead the legal fight against crime and protect our society and its citizens from those who seek to enrich themselves at society’s expense. -

From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, Or Complicity?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, or Complicity? Steven Zeidman* “To meet his constitutional and ethical obligations, a prosecutor should . approach the preparation of a case with a healthy skepticism . He should not assume his witnesses are telling the truth . .”1 “The often close relationship between prosecutors and police make detection of police fabrication unlikely.”2 “[Manhattan District Attorney] Vance’s efforts to make prosecutors smarter . depend on what he calls ‘extreme collaboration’ with the Police Department . working hand in glove with the investigators from the police . ”3 The prosecutor’s constitutional and ethical duty to truth is central to many of Bennett Gershman’s illuminating and trenchant articles about the role of the prosecutor.4 And while ruminating about that obligation conjures up the need for systematic and aggressive investigation while a criminal case is pending, in this essay I argue that nowhere is that duty more critical than at the very moment when a decision is made whether to file charges.5 Specifically, I argue that to meaningfully actualize their duty to truth, prosecutors must extricate themselves from their extant close relationships with the police by adopting a deliberately confrontational approach to police witnesses. Moreover, once a case is charged, they must overcome their longstanding reluctance to liberal disclosure by immediately providing defense counsel with all available discovery. Scholars have written about the complicated relationship between prosecutors * Professor, CUNY School of Law. J.D., Duke University School of Law. -

Blue Lives Matter

COP FRAGILITY AND BLUE LIVES MATTER Frank Rudy Cooper* There is a new police criticism. Numerous high-profile police killings of unarmed blacks between 2012–2016 sparked the movements that came to be known as Black Lives Matter, #SayHerName, and so on. That criticism merges race-based activism with intersectional concerns about violence against women, including trans women. There is also a new police resistance to criticism. It fits within the tradition of the “Blue Wall of Silence,” but also includes a new pro-police movement known as Blue Lives Matter. The Blue Lives Matter movement makes the dubious claim that there is a war on police and counter attacks by calling for making assaults on police hate crimes akin to those address- ing attacks on historically oppressed groups. Legal scholarship has not comprehensively considered the impact of the new police criticism on the police. It is especially remiss in attending to the implications of Blue Lives Matter as police resistance to criticism. This Article is the first to do so. This Article illuminates a heretofore unrecognized source of police resistance to criticism by utilizing diversity trainer and New York Times best-selling author Robin DiAngelo’s recent theory of white fragility. “White fragility” captures many whites’ reluctance to discuss ongoing rac- ism, or even that whiteness creates a distinct set of experiences and per- spectives. White fragility is based on two myths: the ideas that one could be an unraced and purely neutral individual—false objectivity—and that only evil people perpetuate racial subordination—bad intent theory. Cop fragility is an analogous oversensitivity to criticism that blocks necessary conversations about race and policing.