Kari J. Brandtzaeg: Glasgow a Presentation of the Art Scene in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Collecting Scheme Scotland National

National Collecting Scheme Scotland National Collecting Scheme Scotland is an initiative that supports public collections across Scotland to acquire and present challenging contemporary visual art. The initiative also seeks to enable curators within those organisations to extend their knowledge and understanding of contemporary visual arts, and to develop their engagement with the visual arts sector in Scotland. Scotland is home to some very fine public collections, which are of local, national and international significance. It is the aim of the NCSS that those public collections are able to reflect the range and vibrancy of contemporary art created here and abroad, that they can help build new audiences for the contemporary visual arts, as well as engage and work with artists and visual arts organisations. Some facts : • NCSS is an initiative of the Scottish Arts Council. • Currently NCSS has seven museum partners. These are Aberdeen Art Gallery, McManus Galleries, Dundee, Edinburgh City Art Centre, Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow, Hunterian Art Gallery, Paisley Museum and Art Gallery, and the Pier Arts Centre, Orkney. • In its first phase - 2003-2006 - NCSS enabled a total of 122 acquisitions by six public collections (including craft in its first phase). In 2007-2008 a further 18 works of visual art have been acquired. The Scottish Arts Council will support further acquisitions in 2008-2009. • NCSS member were also involved in an innovative joint commissioning project – the first of its kind in the UK. They collaborated to commission Joanne Tatham & Tom O’Sullivan to create a substantial and ambitious new work of art for Scotland • Aberdeen Art Gallery hosted the Scotland & Venice exhibition December 2007- January 2008. -

Translation in the Work of Omer Fast Kelli Bodle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 (Mis)translation in the work of Omer Fast Kelli Bodle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Bodle, Kelli, "(Mis)translation in the work of Omer Fast" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 4069. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4069 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (MIS)TRANSLATION IN THE WORK OF OMER FAST A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Kelli Bodle B.A., Michigan State University, 2002 August 2007 Table of Contents Abstract……...……………………………………………………………………………iii Chapter 1 Documentary and Alienation: Why Omer Fast’s Style Choice and Technique Aid Him in the Creation of a Critical Audience……………………………… 1 2 Postmodern Theory: What Aspects Does Fast Use to Engage Audiences and How Are They Revealed in His Work……………………………………….13 3 Omer Fast as Part of a Media Critique……………………….………………31 4 Artists and Ethics……………….……………………………………………39 5 (Dis)Appearance of Ethics in Omer Fast’s Videos..…………………………53 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..64 Vita...……………………………………………………………………………………..69 ii Abstract For the majority of people, video art does not have a major impact on their daily lives. -

KARLA BLACK Born 1972 in Alexandria, Scotland Lives And

KARLA BLACK Born 1972 in Alexandria, Scotland Lives and works in Glasgow Education 2002-2004 Master of Fine Art, Glasgow School of Art 1999-2000 Master of Philosophy (Art in Organisational Contexts), Glasgow School of Art 1995-1999 BA (Hons) Fine Art, Sculpture, Glasgow School of Art Solo Exhibitions 2021 Karla Black: Sculptures 2000 - 2020, FruitMarket Gallery, Edinburgh 2020 Karla Black: 20 Years, Des Moines Art Centre, Des Moines 2019 Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2018 The Power Plant, Toronto Karla Black / Luke Fowler, Capitain Petzel, Berlin 2017 Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London Festival d’AutoMne, Musée des Archives Nationales and École des Beaux-Arts, Paris MuseuM Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle 2016 Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan A New Order (with Kishio Suga), Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh David Zwirner, New York Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne 2015 Irish MuseuM of Modern Art, Dublin 2014 Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan David Zwirner, New York 2013 Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover Institute of ConteMporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne GeMeenteMuseuM, The Hague 2012 Concentrations 55, Dallas MuseuM of Art, Dallas Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow Stuart Shave / Modern Art, London 2011 Scotland + Venice 2011 (curated by The FruitMarket Gallery), Palazzo Pisani, 54th Venice Biennale, Venice 2010 Capitain Petzel, Berlin WittMann Collection, Ingolstadt -

'The Neo-Avant-Garde in Modern Scottish Art, And

‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ CRAIG RICHARDSON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (BY PUBLISHED WORK) THE SCHOOL OF FINE ART, THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART 2017 1 ‘THE NEO-AVANT-GARDE IN MODERN SCOTTISH ART, AND WHY IT MATTERS.’ Abstract. The submitted publications are concerned with the historicisation of late-modern Scottish visual art. The underpinning research draws upon archives and site visits, the development of Scottish art chronologies in extant publications and exhibitions, and builds on research which bridges academic and professional fields, including Oliver 1979, Hartley 1989, Patrizio 1999, and Lowndes 2003. However, the methodology recognises the limits of available knowledge of this period in this national field. Some of the submitted publications are centred on major works and exhibitions excised from earlier work in Gage 1977, and Macmillan 1994. This new research is discussed in a new iteration, Scottish art since 1960, and in eight other publications. The primary objective is the critical recovery of little-known artworks which were formed in Scotland or by Scottish artists and which formed a significant period in Scottish art’s development, with legacies and implications for contemporary Scottish art and artists. This further serves as an analysis of critical practices and discourses in late-modern Scottish art and culture. The central contention is that a Scottish neo-avant-garde, particularly from the 1970s, is missing from the literature of post-war Scottish art. This was due to a lack of advocacy, which continues, and a dispersal of knowledge. Therefore, while the publications share with extant publications a consideration of important themes such as landscape, it reprioritises these through a problematisation of the art object. -

0-208 Artwork

The North*s Original Free Arts Newspaper + www.artwork.co.uk Number 208 Pick up your own FREE copy and find out what’s really happening in the arts May - June 2019 Shedding Old Coats – one of the haunting works by Karólína Lárusdóttir from a recent exhibition of her work at the Castle Gallery, Inverness. In- side: Denise Wilson tells the story of this Anglo-Icelandic artist. INSIDE: Cultivating Patrick Geddes :: Tapestry Now Victoria Crowe at City Arts :: A northern take on Turner artWORK 208 May/June 2019 Page 2 artWORK 208 May/June 2019 Page 3 CASTLE GALLERY KELSO POTTERY 100 metresmetres behind behind the Kelso Kelso Abbey in the Knowes Car Park. Abbey in The Knowes Car Park. Mugs, jugs, bowls and “TimePorridge Tablets” and Soup fired Bowls, in Piggy theBanks Kelso and Goblets,Pit Kiln. Ovenproof OpenGratin DishesTuesday & Pit-fi to Saturday red Pieces. Open Mon, 10 Braemar Road, 10am-1pm and 2pm-5pm Ballater Thurs, Fri and TelephoneOpen Tues -(01573) Sat 10 to224027 1 - 2 to 5 Sat 10.00 -5.00 AB35 5RL NEWTelephone: SHOP, (01573) DISABLED 224027 ACCESS larksgallery.com facebook/Larks Gallery 013397 55888 CHECK OUT OUR ROBERT GREENHALF OTHER TITLES opening 17th may Jane B. Gibson RMS Wild Wings Over Lonely Shores Scotland’s Premier artWORK kirsty lorenz richard bracken 7th - 29th June www.artwork.co.uk Miniture Portrait Oils and woodcuts inspired by the birds of our jim wright kirstie cohen Painter coast and wetlands by Robert Greenhalf SWLA with hand-carved birds by Michael Lythgoe. West Highland www.resipolestudios.co.uk Open Studio/Gallery Castle Gallery, 43 Castle St, Inverness, IV2 3DU 01463 729512 Wayfarer loch sunart | acharacle | argyll | scotland | ph36 4hx EVERY FRIDAY [email protected] www.westhighlandwayfarer.co.uk or by appointment any www.castlegallery.co.uk THE other time. -

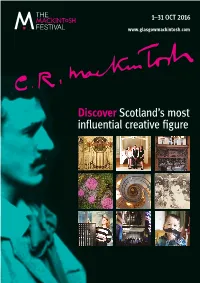

Discoverscotland's Most Influential

1–31 OCT 2016 www.glasgowmackintosh.com Discover Scotland’s most influential creative figure A Charles Rennie Mackintosh The Mackintosh Festival is organised 1868–1928. by members of Glasgow Mackintosh: Architect. Artist. Designer. Icon. Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum The work of the Scottish architect, designer Scotland Street School Museum and artist, Charles Rennie Mackintosh is today The Glasgow School of Art celebrated internationally. Mackintosh was one Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society of the most sophisticated exponents of the House for An Art Lover theory of the room as a work of art, and created The Hunterian distinctive furniture of great formal elegance. In The Hill House Glasgow, you will see the finest examples of his The Lighthouse buildings and interiors and examples of his creative The Glasgow Art Club collaborations with his wife, the accomplished Glasgow Museums Resource Centre (GMRC) artist and designer Margaret Macdonald. Mackintosh Queen’s Cross Special thanks to our partners: GBPT Doors Open Day Glasgow Women’s Library The Willow Tea Rooms The Glad Café Glasgow City Marketing Bureau Glasgow Restaurateurs Association Welcome to the fifth Mackintosh Festival Glasgow Mackintosh is delighted to present another month-long programme of over 40 arts and cultural events to celebrate the life of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Glasgow’s most famous architect, designer and artist. This year we are celebrating House – where you can celebrate installation of Kathy Hinde’s the 2016 Year of Innovation, their 20th birthday with kids -

Argyll & the Isles

EXPLORE 2020-2021 ARGYLL & THE ISLES Earra-Ghàidheal agus na h-Eileanan visitscotland.com Contents The George Hotel 2 Argyll & The Isles at a glance 4 Scotland’s birthplace 6 Wild forests and exotic gardens 8 Island hopping 10 Outdoor playground 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 38 Leisure activities 40 Shopping Welcome to… 42 Food & drink 46 Tours ARGYLL 49 Transport “Classic French Cuisine combined with & THE ISLES 49 Events & festivals Fáilte gu Earra-Gháidheal ’s 50 Accommodation traditional Scottish style” na h-Eileanan 60 Regional map Extensive wine and whisky selection, Are you ready to fall head over heels in love? In Argyll & The Isles, you’ll find gorgeous scenery, irresistible cocktails and ales, quirky bedrooms and history and tranquil islands. This beautiful region is Scotland’s birthplace and you’ll see castles where live music every weekend ancient kings were crowned and monuments that are among the oldest in the UK. You should also be ready to be amazed by our incredibly Cover: Crinan Canal varied natural wonders, from beavers Above image: Loch Fyne and otters to minke whales and sea eagles. Credits: © VisitScotland. Town Hotel of the Year 2018 Once you’ve started exploring our Kenny Lam, Stuart Brunton, fascinating coast and hopping around our dozens of islands you might never Wild About Argyll / Kieran Duncan, want to stop. It’s time to be smitten! Paul Tomkins, John Duncan, Pub of the Year 2019 Richard Whitson, Shane Wasik/ Basking Shark Scotland, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh / Bar Dining Hotel of the Year 2019 Peter Clarke 20ARS Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM). -

Jim Lambie Education Solo Exhibitions & Projects

FUNCTIONAL OBJECTS BY CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ! ! ! ! !JIM LAMBIE Born in Glasgow, Scotland, 1964 !Lives and works in Glasgow ! !EDUCATION !1980 Glasgow School of Art, BA (Hons) Fine Art ! !SOLO EXHIBITIONS & PROJECTS 2015 Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) Zero Concerto, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia Sun Rise, Sun Ra, Sun Set, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2014 Answer Machine, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013 The Flowers of Romance, Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong! 2012 Shaved Ice, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland Metal Box, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin, Germany you drunken me – Jim Lambie in collaboration with Richard Hell, Arch Six, Glasgow, Scotland Everything Louder Than Everything Else, Franco Noero Gallery, Torino, Italy 2011 Spiritualized, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY Beach Boy, Pier Art Centre, Orkney, Scotland Goss-Michael Foundation, Dallas, TX 2010 Boyzilian, Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris, France Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, Scotland Metal Urbain, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland! 2009 Atelier Hermes, Seoul, South Korea ! Jim Lambie: Selected works 1996- 2006, Charles Riva Collection, Brussels, Belgium Television, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2008 RSVP: Jim Lambie, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA ! Festival Secret Afair, Inverleith House, Ediburgh, Scotland Forever Changes, Glasgow Museum of Modern Art, Glasgow, Scotland Rowche Rumble, c/o Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin, Germany Eight Miles High, ACCA, Melbourne, Australia Unknown Pleasures, Hara Museum of -

Craft Generation Booklet CLAIRE BARCLAY

CLAIRE BARCLAY Untitled Element from ‘Shadow Spans’ by Claire Barclay 2010 Shellac, calico, fur felt 22cm x 18cm x height 24cm From the installation work ‘Shadow Spans’ at The Whitechapel Gallery, London. The installation reflected on the nature of liminal spaces on the boundaries of indoors and outdoors, for example, the porch, the entrance, windows and doors, the pavement etc. The sculptural components were in some way exploring aspects of the transitions we experience between private and public space. This hat-like form suggestive of a shift from formal to informal when removed at the point of entering a building. It is also abstracted from its familiar form and so made odd and dysfunctional. 3 CLAIRE BARCLAY Where are you based? Based in Glasgow - work in the Glasgow Sculpture Studios, Glasgow Print Studio, studio at home, work with other fabricators, engineering company, saddlers, fabric printing facilities. What is your definition / the definition you prefer of craft? Craft is present in all disciplines where hand skills evolve over time through the exploration of and fascination with particular tasks, whether practical or absurd, traditional or improvised. How does craft relate to your practice as an artist? I don’t consciously think of myself as craft- ing while I am making, as I do not have a specific goal in mind. The materials and processes I use are determined more often by the context in which I am working. I try to use each project as an opportunity to learn more skills but if the skills needed are beyond my ability, I need to work in collaboration with experts in order to realize the work. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica ISSN: 1989-8975 Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública (INAP) Forte, Pierpaolo Breves consideraciones sobre la adquisición de obras de arte en la regulación europea de los contratos públicos Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. 8, 2017, Noviembre-Abril, pp. 97-115 Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública (INAP) DOI: 10.24965/reala.v0i8.10436 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=576462577005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Recibido: 22-06-2017 Aceptado: 09-10-2017 DOI: 10.24965/reala.v0i8.10436 Breves consideraciones sobre la adquisición de obras de arte en la regulación europea de los contratos públicos Brief considerations on the acquisition of works of art in the European regulation of public contracts Pierpaolo Forte Università degli studi del Sannio [email protected] RESUMEN La obra, renunciando a una definición precisa de arte, reconoce que hay objetos de arte y objetos culturales, que, propiamente en esa capacidad, son relevantes también en términos legales, y trata de avanzar algunas reflexiones sobre la relevancia del arte en relación con la disciplina europea de contratos públicos y, en particular, con lo que puede deducirse de la Directiva 2014/24/UE, que puede entenderse como una especie de signo cultural capaz de ofrecer indicaciones sobre cómo se percibe el arte en Europa, también en términos políticos, en esta fase histórica. -

The Magazine of the Glasgow School of Art Issue 1

Issue 1 The Magazine of The Glasgow School of Art FlOW ISSUE 1 Cover Image: The library corridor, Mackintosh Building, photo: Sharon McPake >BRIEFING Funding increase We√come Research at the GSA has received a welcome cash boost thanks to a rise in Welcome to the first issue of Flow, the magazine of The Glasgow School of Art. funding from the Scottish Higher Education Funding In this issue, Ruth Wishart talks to Professor Seona Reid about the changes and Council (SHEFC).The research challenges ahead for Scotland’s leading art school. This theme is continued by grant has risen from £365,000 to £1.3million, as a result Simon Paterson, GSA Chairman, in his interview Looking to the Future which of the Research Assessment outlines the exciting plans the School has to transform its campus into a Exercise carried out in 2001. world-class learning environment. President’s dinner A dinner to encourage Creating a world-class environment for teaching and research is essential if potential ambassadors for the GSA was held in the the GSA is to continue to contribute to Scotland, the UK and beyond. Every Mackintosh Library by Lord year 300 students graduate from the GSA and Heather Walton talks to some Macfarlane of Bearsden, the School’s Honorary President. of them about the role the GSA plays in the cultural, social and economic life In his after dinner speech, Lord of the nation. One such graduate is the artist Ken Currie, recently appointed Wilson of Tillyorn, the recently appointed Chairman of the Visiting Professor within the School of Fine Art, interviewed here by Susannah National Museums of Scotland, Thompson. -

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Humanities And

Temporality and the Evocation of Fear and Unease in Selected Video Installations Patricia Driscoll A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Fine Arts by Dissertation. Johannesburg, 2012 Declaration: I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Fine Arts in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. _________________________ Patricia Driscoll __________ day of _________, 2012 ii Abstract: In this research I explore the evocation of fear and unease in selected video installations and how time impacts upon such evocation. For this purpose I consider the works of selected contemporary artists who deal directly with a form of time-based hyper-awareness linked to the experience of trauma, fear and panic. Amongst others, I discuss selected video artworks by Douglas Gordon, Ed Atkins, and South African artists William Kentridge, Kendell Geers and Berni Searle. I examine how such artworks engage with the expansion and collapse of time and experiences of being stuck or being absorbed in a significant moment. In undertaking this research I closely examine the mediums of film and video as well as contexts and the installation formats in which they are presented. I explore similar aspects of evoking unease in my own video installation titled Night-light and the supporting video work submitted for this degree. My previous creative experience has been in still photography in which I had become interested in exploring the capturing of time and movement and imparting an immersive temporal dimension or an extended moment in time in the still image.