Wada, Yoshihide Increasing Dependence of Lowland Populations on Mountain Water Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Environmental Report on Thailand

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT ON THAILAND PREPARED BY THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIVISION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. AID/DS/ST CONTRACT NO, SA/TOA 1-77 WITH U.S. MAN AND THE BIOSPHERE SECRETARIAT DEPARTMENT OF STATE WASHINGTON, D.C. OCTOBER 1979 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF THAILAND Table of Contents Section page Introduction and Summary ii 1.0 Populat i h,ht'<eristics 1.1 Get i I p ition statistics .................................. 1 1.2 Sp i 1 ibution ........................................... 2 1.3 Ethr .."d religion ......................................... 6 1.4 Education ............ ......................................... 7 1.5 Health ........................................................ 8 1.6 Birth control and population policy.............................9 2.0 The Economy 2.1 General economic statistics .................................... 11 2.2 Economic structure and growth .................................. 13 3.0 Resources and Environmental Problems 3.1 Topography and climate ......................................... 17 3.2 Freshwater ..................................................... 21 3.3 Soils .......................................................... 26 3.4 Minerals ....................................................... 28 3.5 Forests ........................................................ 30 3.6 Coastal zone ................................................... 35 3.7 Wildlife ....................................................... 38 3.8 Fisheries ..................................................... -

Assessment of Tourist Site Potential and Application of Environmental

$4.60 ASSESSMENT OF TOURIST SITE POTENTIAL AND APPLICATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR ECOTOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN SRI NAN NATIONAL PARK. NAN PROVINCE Miss Tatsanawalai Utarasakul A Dissertation submitted in Partial Futfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorof Philosophy program in Environmentalscience (l nterdisciplinary Program) Graduate School Chulalongkom Univeaity Academic Year 2007 Copyright of Chutatongkom University I I Ts8T0g BpwrornBlusu lurttL]o3gt u3g 0992 truEstuE B-u rBraEL nBps u suurL BpmrEU g?ulr (ulguruunu) Bopuonlgu ury rBrrgrsEr3ru u grug[nUsu Eru r BrrErfu fu gnru SupnnwunuBsru ]gr]pnncpnErpgnrEmr g ulrusureU Bpcmr1tcrt ]m nqru!n*, nqql, Er3lpnnunuunlu orss gl oBpl lolrsLuLnrulBru opl Bopu cnlgsru U1^ruu nn:cy uh:c Juru: un cBpt $qrlpnnlonrwnugn$:sFsru Thesis Title ASSESSMENT OF TOURIST SITE POTENTIAL AND APPLICATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEM FOR ECOTOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN SRINAN NATIONAL PARK. NAN PROVINCE By Miss Tatsanawalai Utarasakul Field of Study Environmental Science Thesis Advisor Associate Professor Kumthorn Thirakhupt, Ph.D. Thesis Co-advisor Assistant Professor Art-ong Pradatsundarasar, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School, Chulalongkorn Universig in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctoral Degree htTfi: Dean of the Graduate School (A.ssistant Professor M.R. Kalaya Tingsabadh.Ph.D.) THESIS COMMITTEE e. 1,6 ;. ;.h.r4p. :l.|- .... ... chairman (Assistant Professor Chamwit Kositanont. Ph.D.) Thesis Advisor (Associate Professor Kumthom Thirakhupt. Ph.D. ) ?d"b Thesis Co-advisor (Assistant Professor Art-ong Pradatsundarasar. Ph.D.) it* ExternalMember Member (Associate Professor Thavivongse Sriburi, Ph.D.) It.. i-' ....(?....:.. LEs t i rt09 r'*u bt ssgognt u s ;'a,li; i! ;;,;; tif 91 Ellst tnugsuup ......St-.:"g.....::gnp*tbr,sspeEBuu""""""""""""ossz" U n*Upi,6n6p}u BuJuBnE.... -

Did the Construction of the Bhumibol Dam Cause a Dramatic Reduction in Sediment Supply to the Chao Phraya River?

water Article Did the Construction of the Bhumibol Dam Cause a Dramatic Reduction in Sediment Supply to the Chao Phraya River? Matharit Namsai 1,2, Warit Charoenlerkthawin 1,3, Supakorn Sirapojanakul 4, William C. Burnett 5 and Butsawan Bidorn 1,3,* 1 Department of Water Resources Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (W.C.) 2 The Royal Irrigation Department, Bangkok 10300, Thailand 3 WISE Research Unit, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 4 Department of Civil Engineering, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Pathumthani 12110, Thailand; [email protected] 5 Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +66-2218-6455 Abstract: The Bhumibol Dam on Ping River, Thailand, was constructed in 1964 to provide water for irrigation, hydroelectric power generation, flood mitigation, fisheries, and saltwater intrusion control to the Great Chao Phraya River basin. Many studies, carried out near the basin outlet, have suggested that the dam impounds significant sediment, resulting in shoreline retreat of the Chao Phraya Delta. In this study, the impact of damming on the sediment regime is analyzed through the sediment variation along the Ping River. The results show that the Ping River drains a mountainous Citation: Namsai, M.; region, with sediment mainly transported in suspension in the upper and middle reaches. By contrast, Charoenlerkthawin, W.; sediment is mostly transported as bedload in the lower basin. Variation of long-term total sediment Sirapojanakul, S.; Burnett, W.C.; flux data suggests that, while the Bhumibol Dam does effectively trap sediment, there was only a Bidorn, B. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Aim Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Highland Cash Crop Development and Biodiversity Conservation: The Hmong in Northern Thailand by Waranoot Tungittiplakorn B.Sc., Chulalongkorn University, 1988 M..Sc., Asian Institute of Technology, 1991 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment o f the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Geography We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Dr. -

Dawna Tenasserim Landscape

• DAWNA TENASSERIM LANDSCAPE TENASSERIM DAWNA LEAFLET FEBRUARY 2014 PANDA.ORG/GREATERMEKONG WWF-Greater Mekong DAWNA TENASSERIM LANDSCAPE Jitvijak / WWF-Thailand © Wayuphong The landscape includes 30,539km2 of protected areas and nearly 50,000km2 of wilderness area, providing shelter to over 150 mammals and nearly 570 bird species. © WWF-Greater Mekong DAWNA TENASSERIM LANDSCAPE WWF is conserving the Dawna Tenasserim Landscape as an intact ecosystem with protected and connected habitats for wildlife, and safeguarding its valuable ecosystem services for local communities and the nations of Myanmar and Thailand. The Dawna Tenasserim Landscape, which covers 63,239 km² of Thailand and Myanmar, is defined by the Dawna and Tenasserim mountain ranges. These mountains are the source for the region’s major rivers and watershed systems: the Tenasserim, in the Taninthayi Region of Myanmar, and the Mae Khlong, Chao Phraya, Phetchaburi, and Lower Western watershed systems in Thailand. Ancient human civilizations have risen and fallen in this landscape, and the area is home to diverse ethnic groups who have thrived there for centuries. The Myanmar portion of this landscape receives heavy rainfall and supports some of the largest areas of lowland evergreen forest remaining in the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot. The Thai side is dryer and is covered by a mosaic of evergreen and deciduous forests. The Dawna Tenasserim Landscape also contains one of the largest protected area networks in Southeast Asia, formed by the contiguous Western Forest Complex and Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex THE DAWNA TENASSERIM in Thailand. Additional protected areas are proposed for the forests in Myanmar as well. LANDSCAPE CONTAINS Flagship Species ONE OF THE LARGEST From the tiny endemic Kitti’s hog-nosed bat (also known as the bumblebee bat), contender PROTECTED AREA for the title of smallest mammal in the world, to the Asian elephant, the Dawna Tenasserim is home to a remarkable diversity of animals. -

Decisions Adopted by the World Heritage Committee at Its 37Th Session (Phnom Penh, 2013)

World Heritage 37 COM WHC-13/37.COM/20 Paris, 5 July 2013 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE World Heritage Committee Thirty-seventh session Phnom Penh, Cambodia 16 - 27 June 2013 DECISIONS ADOPTED BY THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE AT ITS 37TH SESSION (PHNOM PENH, 2013) Table of content 2. Requests for Observer status ................................................................................ 3 3A. Provisional Agenda of the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee (Phnom Penh, 2013) ......................................................................................................... 3 3B. Provisional Timetable of the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee (Phnom Penh, 2013) ......................................................................................................... 3 5A. Report of the World Heritage Centre on its activities and the implementation of the World Heritage Committee’s Decisions ................................................................... 4 5B. Reports of the Advisory Bodies ................................................................................. 5 5C. Summary and Follow-up of the Director General’s meeting on “The World Heritage Convention: Thinking Ahead” (UNESCO HQs, 2-3 October 2012) ............................. 5 5D. Revised PACT Initiative Strategy............................................................................ 6 5E. Report on -

Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors

About the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors The transformation of transport corridors into economic corridors has been at the center of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program since 1998. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted this Assessment to guide future investments and provide benchmarks for improving the GMS economic corridors. This Assessment reviews the state of the GMS economic corridors, focusing on transport infrastructure, particularly road transport, cross-border transport and trade, and economic potential. This assessment consists of six country reports and an integrative report initially presented in June 2018 at the GMS Subregional Transport Forum. About the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program The GMS consists of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, the People’s Republic of China (specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1992, with assistance from the Asian Development Bank and building on their shared histories and cultures, the six countries of the GMS launched the GMS Program, a program of subregional economic cooperation. The program’s nine priority sectors are agriculture, energy, environment, human resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade facilitation. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining -

A Biogeographic Synthesis of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Indochina

BAIN & HURLEY: AMPHIBIANS OF INDOCHINA & REPTILES & HURLEY: BAIN Scientific Publications of the American Museum of Natural History American Museum Novitates A BIOGEOGRAPHIC SYNTHESIS OF THE Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF INDOCHINA Publications Committee Robert S. Voss, Chair Board of Editors Jin Meng, Paleontology Lorenzo Prendini, Invertebrate Zoology RAOUL H. BAIN AND MARTHA M. HURLEY Robert S. Voss, Vertebrate Zoology Peter M. Whiteley, Anthropology Managing Editor Mary Knight Submission procedures can be found at http://research.amnh.org/scipubs All issues of Novitates and Bulletin are available on the web from http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace Order printed copies from http://www.amnhshop.com or via standard mail from: American Museum of Natural History—Scientific Publications Central Park West at 79th Street New York, NY 10024 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (permanence of paper). AMNH 360 BULLETIN 2011 On the cover: Leptolalax sungi from Van Ban District, in northwestern Vietnam. Photo by Raoul H. Bain. BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY A BIOGEOGRAPHIC SYNTHESIS OF THE AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF INDOCHINA RAOUL H. BAIN Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Herpetology) and Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History Life Sciences Section Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, ON Canada MARTHA M. HURLEY Center for Biodiversity and Conservation, American Museum of Natural History Global Wildlife Conservation, Austin, TX BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 360, 138 pp., 9 figures, 13 tables Issued November 23, 2011 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2011 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract......................................................... -

Population Structure and Dynamics of the Endangered Tree Tetracentron Sinense Oliver

Pak. J. Bot., 52(2): 613-619, 2020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.30848/PJB2020-2(4) POPULATION STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS OF THE ENDANGERED TREE TETRACENTRON SINENSE OLIVER WENYING LI1,2Ɵ, HUAICHUN LI1,2Ɵ, XIAOHONG GAN1,2*, XUEMEI ZHANG1,2 AND ZENGLI FAN1,2 1Key Laboratory of Southwest China Wildlife Resources Conservation (Ministry of Education), Nanchong 637009, China 2Institute of Plant Adaptation and Utilization in Southwest Mountain, China West Normal University, Nanchong 637009, China *Correspondence author’s email: [email protected]; [email protected] ƟAuthor’s contribute equally to this work Abstract Tetracentron sinense is an endangered tree in China in appendix III of CITES. The current status and dynamics of wild population of T. sinense are unknown, but are vital to its conservation. Diameter at breast height (or basal height for individuals <2.5 m) of all individuals of the T. sinense population in Meigu Dafengding Nature Reserve was investigated. Population size structure, time-specific life tables, survival analysis, and time series analysis were used to analyze the conservation status and dynamics of a natural population. The size structure of the population showed a spindle shape, with few younger individuals (including seedling and sapling) being present, and more middle-aged and aged individuals. The survival curve was a Deevey-type II. The mortality rate, killing power, mortality density, and hazard rate of the population all peaked in the 6th and 12th age-classes. In the first six age-classes, survival rate decreased monotonically, while the cumulative mortality rate rapidly increased, after which the change in trend became relatively gentle. -

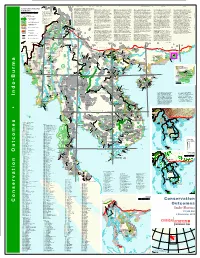

C O N S E R V a Tio N O U Tc O M E S • in D O -B U R

Conservation Outcomes Geographic Priorities for Investment This map presents a set of geographic targets for The Ecosystem Profile includes an investment Globally threatened mammals endemic to Hainan tributaries, including the Srepok, Sesan, and of high global importance for plant conservation, important congregations of globally threatened conservation action within the Indo-Burma strategy for engaging civil society organizations in Island include Hainan hare (Lepus hainanus) Sekong (Xe Kong) rivers, represent one of the supporting high levels of endemism in many species, such as greater adjutant (Leptoptilos Indo-Burma The political and geographic 50 0 50 100 150 200 Hotspot, at site (Key Biodiversity Area) and intiatives that address threats to biodiversity, Hainan gymnure (Neohylomys hainanensis) and best remaining examples of the riverine groups, such as orchids. The corridor supports dubius). The extensive area of flooded forest and designations shown on this map do not imply the expression of any landscape (conservation corridor) scales. The communities and livelihoods. The investment Hainan gibbon (Nomascus hainanus). The latter ecosystems of Indo-Burma, and provide services the richest assemblages of conifer species in the high levels of nutrients transported by the annual kilometers targets were defined through a consultative strategy focuses on those taxonomic, geographic species is believed to be entirely confined to vital to the livelihoods of millions of people. The region, including several globally threatened flood result -

Genetic Structure of the Red-Spotted Tokay Gecko, Gekko Gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Mainland Southeast Asia

Asian Herpetological Research 2019, 10(2): 69–78 ORIGINAL ARTICLE DOI: 10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.180066 Genetic Structure of the Red-spotted Tokay Gecko, Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Mainland Southeast Asia Weerachai SAIJUNTHA1, Sutthira SEDLAK1, Takeshi AGATSUMA2, Kamonwan JONGSOMCHAI3, Warayutt PILAP1, Watee KONGBUNTAD4, Wittaya TAWONG5, Warong SUKSAVATE1, Trevor N. PETNEY6 and Chairat TANTRAWATPAN7* 1 Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Biodiversity and Conservation Research Unit, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand 2 Department of Environmental Medicine, Kochi Medical School, Kochi University, Oko, Nankoku, Kochi 783-8505, Japan 3 Department of Anatomy, School of Medical Science, Phayao University, Phayao 56000, Thailand 4 Program in Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Maejo University, Chiang Mai 50290, Thailand 5 Department of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok 65000, Thailand 6 Department of Paleontology and Evolution, State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe, Erbprinzenstrasse 13, Karlsruhe 76133, Germany 7 Division of Cell Biology, Department of Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Rangsit Campus, Pathumthani 12120, Thailand Abstract This study was performed to explore the genetic diversity and genetic structure of red-spotted tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) from 23 different geographical areas in Thailand, Lao PDR and Cambodia. The mitochondrial tRNA- Gln/tRNA-Met/partial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 from 166 specimens was amplified and sequenced. A total of 54 different haplotypes were found. Highly significant genetic differences occurred between populations from different localities. The haplotype network revealed six major haplogroups (G1 to G6) belonging to different clades (clade A– E). Clade D and clade E were newly observed in this study. -

Analysis of Temporal and Spatial Variations in Hydrometeorological

167 © 2019 The Authors Journal of Water and Climate Change | 10.1 | 2019 Analysis of temporal and spatial variations in hydrometeorological elements in the Yarkant River Basin, China Ren-juan Wei, Liang Peng, Chuan Liang, Christoph Haemmig, Matthias Huss, Zhen-xia Mu and Ying He ABSTRACT Yarkant River is a tributary of Tarim River in China, and the basin lacks observational data. To investigate Ren-juan Wei Chuan Liang past climatic variations and predict future climate changes, precipitation, air temperature and runoff State Key Laboratory of Hydraulics and Mountain River Engineering, data from Kaqun hydrological station are analysed at monthly and seasonal scales using detrended College of Water Resource and Hydropower, fluctuation analysis (DFA). Results show that DFA scaling exponents of monthly precipitation, air Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, temperature and runoff are 0.535, 0.662 and 0.582, respectively. These three factors all show China long-range correlations. Their increasing trends will continue in the near future as the climate shifts Ren-juan Wei Sichuan Water Conservancy Vocational College, towards warmer and more humid. Spring and winter precipitation exhibit long-range correlations and Chengdu 611200, will increase in the future. In contrast, summer and autumn precipitation exhibits random fluctuations China and does not show stable trends. Air temperature during all seasons exhibits long-range correlations Liang Peng (corresponding author) Zhen-xia Mu and will continue to increase in the future. Runoff during the spring and summer exhibits weak anti- Ying He College of Water Conservancy and Civil persistence, but autumn and winter runoff show long-range correlations and increasing trends.