The Politics of Understanding: Language As a Model of Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Far Horizon

The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Danny Wool, Lorna Hanrahan, Mary Musser, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team THE FAR HORIZON BY LUCAS MALET (MRS. MARY ST. LEGER HARRISON) BY THE SAME AUTHOR _The Wages of Sin_ _A Counsel of Perfection_ page 1 / 464 _Colonel Enderby's Wife_ _Little Peter_ _The Carissima_ _The Gateless Barrier_ _The History of Sir Richard Calmady_ "Ask for the Old Paths, where is the Good Way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest."--JEREMIAS. "The good man is the bad man's teacher; the bad man is the material upon which the good man works. If the one does not value his teacher, if the other does not love his material, then despite their sagacity they must go far astray. This is a mystery of great import."--FROM THE SAYINGS OF LAO-TZU. ..."Cherchons a voir les choses comme elles sont, et ne voulons pas avoir plus d'esprit que le bon Dieu! Autrefois on croyait que la canne a sucre seule donnait le sucre, on en tire a peu pres de tout maintenant. Il est de meme de la poesie. Extrayons-la de n'importe quoi, car elle git en page 2 / 464 tout et partout. Pas un atome de matiere qui ne contienne pas la poesie. Et habituons-nous a considerer le monde comme un oeuvre d'art, dont il faut reproduire les procedees dans nos oeuvres."--GUSTAVE FLAUBERT. CHAPTER I Dominic Iglesias stood watching while the lingering June twilight darkened into night. -

Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and the Appropriation of Huayan Thought

Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and the Appropriation of Huayan Thought A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 King Pong Chiu School of Arts, Languages and Cultures TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 List of Figures and Tables 4 List of Abbreviations 5 Abstract 7 Declaration and Copyright Statement 8 A Note on Transliteration 9 Acknowledgements 10 Chapter 1 - Research Questions, Methodology and Literature Review 11 1.1 Research Questions 11 1.2 Methodology 15 1.3 Literature Review 23 1.3.1 Historical Context 23 1.3.2 Thomé H. Fang and Huayan Thought 29 1.3.3 Tang Junyi and Huayan Thought 31 Chapter 2 – The Historical Context of Modern Confucian Thinkers’ Appropriations of Buddhist Ideas 33 2.1 ‘Ti ’ and ‘Yong ’ as a Theoretical Framework 33 2.2 Western Challenge and Chinese Response - An Overview 35 2.2.1 Declining Status of Confucianism since the Mid-Nineteenth Century 38 2.2.2 ‘Scientism’ as a Western Challenge in Early Twentieth Century China 44 2.2.3 Searching New Sources for Cultural Transformation as Chinese Response 49 2.3 Confucian Thinkers’ Appropriations of Buddhist Thought - An Overview 53 2.4 Classical Huayan Thought and its Modern Development 62 2.4.1 Brief History of the Huayan School in the Tang Dynasty 62 2.4.2 Foundation of Huayan Thought 65 2.4.3 Key Concepts of Huayan Thought 70 2.4.4 Modern Development of the Huayan School 82 2.5 Fang and Tang as Models of ‘Chinese Hermeneutics’- Preliminary Discussion 83 Chapter 3 - Thomé H. -

X********X************************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 264 IR 052 601 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo, Ed. TITLE Iowa and Some Iowans. A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 312p.; Fcr a supplement to the second edition, see ED 227 842. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibllographies; *Authors; Books; Directories; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; History Instruction; Learning Resources Centers; *Local Color Writing; *Local History; Media Specialists; Nonfiction; School Libraries; *State History; United States History; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT Prepared primarily by the Iowa State Department of Education, this annotated bibliography of materials by Iowans or about Iowans is a revised tAird edition of the original 1969 publication. It both combines and expands the scope of the two major sections of previous editions, i.e., Iowan listory and literature, and out-of-print materials are included if judged to be of sufficient interest. Nonfiction materials are listed by Dewey subject classification and fiction in alphabetical order by author/artist. Biographies and autobiographies are entered under the subject of the work or in the 920s. Each entry includes the author(s), title, bibliographic information, interest and reading levels, cataloging information, and an annotation. Author, title, and subject indexes are provided, as well as a list of the people indicated in the bibliography who were born or have resided in Iowa or who were or are considered to be Iowan authors, musicians, artists, or other Iowan creators. Directories of periodicals and annuals, selected sources of Iowa government documents of general interest, and publishers and producers are also provided. -

The Arid Soils of the Balikh Basin (Syria)

THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYRIA) M.A. MULDERS ERRATA THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYRIA). M.A. MULDERS, 1969 page 21, line 2 from bottom: read: 1, 4 instead of: 14 page 81, line 1 from top: read: x instead of: x % K page 103t Fig» 19: read: phytoliths instead of: pytoliths page 121, profile 51, 40-100 cm: read: clay instead of: silty clay page 125, profile 26, 40-115 cm: read: silt loam instead of: clay loam page 127, profile 38, 105-150 cm: read: clay instead of: silty loam page 127, profile 42, 14-40 cm: read: silty clay loam instead of: silt loam page 127, profile 42, 4O-6O cm: read: silt loam instead of: clay loam page 138, 16IV, texture: read: 81,5# sand, 14,4% silt instead of: 14,42! sand, 81.3% silt page 163, add: A and P values (quantimet), magnification of thin sections 105x THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYEIA). M.A. MULDERS, 19Ô9 page 18, Table 2: read: mm instead of: min page 80, Fig. 16: read: kaolinite instead of: kaolite page 84, Table 21 : read: Kaolinite instead of: Kaolonite page 99, line 17 from top: read: at instead of: a page 106, line 20 from bottom: read: moist instead of: most page 109t line 8 from bottom: read: recognizable instead of: recognisable page 115» Fig. 20, legend: oblique lines : topsoil, 0 - 30 cm horizontal lines : deeper subsoil, 60 - 100 cm page 159» line 6 from top: read: are instead of: is 5Y THE ARID SOILS OF THE BAUKH BASIN (SYRIA) 37? THE ARID SOILS OF THE BALIKH BASIN (SYRIA) PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE WISKUNDE EN NATUURWETENSCHAPPEN AAN DE RIJKS- UNIVERSITEIT TE UTRECHT, OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS, PROF.DR. -

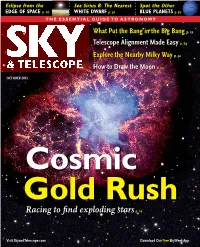

Sky & Telescope

Eclipse from the See Sirius B: The Nearest Spot the Other EDGE OF SPACE p. 66 WHITE DWARF p. 30 BLUE PLANETS p. 50 THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO ASTRONOMY What Put the Bang in the Big Bang p. 22 Telescope Alignment Made Easy p. 64 Explore the Nearby Milky Way p. 32 How to Draw the Moon p. 54 OCTOBER 2013 Cosmic Gold Rush Racing to fi nd exploding stars p. 16 Visit SkyandTelescope.com Download Our Free SkyWeek App FC Oct2013_J.indd 1 8/2/13 2:47 PM “I can’t say when I’ve ever enjoyed owning anything more than my Tele Vue products.” — R.C, TX Tele Vue-76 Why Are Tele Vue Products So Good? Because We Aim to Please! For over 30-years we’ve created eyepieces and telescopes focusing on a singular target; deliver a cus- tomer experience “...even better than you imagined.” Eyepieces with wider, sharper fields of view so you see more at any power, Rich-field refractors with APO performance so you can enjoy Andromeda as well as Jupiter in all their splendor. Tele Vue products complement each other to pro- vide an observing experience as exquisite in performance as it is enjoyable and effortless. And how do we score with our valued customers? Judging by superlatives like: “in- credible, truly amazing, awesome, fantastic, beautiful, work of art, exceeded expectations by a mile, best quality available, WOW, outstanding, uncom- NP101 f/5.4 APO refractor promised, perfect, gorgeous” etc., BULLSEYE! See these superlatives in with 110° Ethos-SX eye- piece shown on their original warranty card context at TeleVue.com/comments. -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

Flashback, Flash Forward: Re-Covering the Body and Id-Endtity in the Hip-Hop Experience

FLASHBACK, FLASH FORWARD: RE-COVERING THE BODY AND ID-ENDTITY IN THE HIP-HOP EXPERIENCE Submitted By Danicia R. Williams As part of a Tutorial in Cultural Studies and Communications May 04,2004 Chatham College Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Tutor: Dr. Prajna Parasher Reader: Ms. Sandy Sterner Reader: Dr. Robert Cooley ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Prajna Paramita Parasher, my tutor for her faith, patience and encouragement. Thank you for your friendship. Ms. Sandy Sterner for keeping me on my toes with her wit and humor, and Dr. Cooley for agreeing to serve on my board. Kathy Perrone for encouraging me always, seeing things in me I can only hope to fulfill and helping me to develop my writing. Dr. Anissa Wardi, you and Prajna have changed my life every time I attend your classes. My parent s for giving me life and being so encouraging and trusting in me even though they weren't sure what I was up to. My Godparents, Jerry and Sharon for assisting in the opportunity for me to come to Chatham. All of the tutorial students that came before me and all that will follow. I would like to give thanks for Hip-Hop and Sean Carter/Jay-Z, especially for The Black Album. With each revolution of the CD my motivation to complete this project was renewed. Whitney Brady, for your excitement and brainstorming sessions with me. Peace to Divine Culture for his electricity and Nabri Savior. Thank you both for always being around to talk about and live in Hip-Hop. Thanks to my friends, roommates and coworkers that were generally supportive. -

Hip Deep Opinion, Essays, and Vision from American Teenagers

hip deep Opinion, Essays, and Vision from American Teenagers edited by abe louise young with the Youth Board of Next Generation Press next generationpress Copyright © by Next Generation Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by Next Generation Press Printed in China by Kwong Fat Offset Printing Co. Ltd. Distributed by National Book Network, Lanham, Maryland ISBN --- Book design by Sandra Delany Next Generation Press, a not-for-profit book publisher, brings forward the voices and views of adolescents on their own lives, language, learning, and work. With a particular focus on youth without privilege, Next Generation Press raises awareness of young people as a powerful force for social justice. Next Generation Press, P.O. Box , Providence, RI www.nextgenerationpress.org Contents preface. vii Dixie Goswami introduction: it’s hip to be deep. ix anote for teachers. .xii and others who care about young people’s reading and writing 1. “Connected by Courage”: Experiences of Family . Della Jenkins . .. Maria Maldonado . Brittany Cavallaro . Nicole Schwartzberg . Daniel Cacho . Anonymous . Cat deLuna ’ : . Theresa Staruch ’ . Blanca Garcia . Dylan Oteri 2. “My Voice Is an Independent Song”: My School, My Path, My Learning . Eric Green . Jane S. Jiang . Stephanie Compton ’ . Daniel Omar Araniz ’. John Wood . Alice Nam : . Élan Jade Jones . Daniel Klotz . Jane S. Jiang ’ . James Slusser . Bessie Jones . Candace Coleman 3. “Because It’s Mine, and Because Ain’t Nobody Just Gonna Take It from Me”: Living in the Body I Have . Telvi Altamirano . -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

Thesis-20.Pdf (4.452Mb)

Factors Influencing Biotite Weathering by Ryan Ronald Reed Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Crop and Soil Environmental Sciences APPROVED: Dr. Lucian Zelazny Dr. James Baker (Committee Chair) Dr. Matthew Eick Dr. Jack Hall (Department Head) December, 2000 Blacksburg, Virginia R.Reed ii Factors Influencing Biotite Weathering by Ryan Reed Lucian W. Zelazny, Chairman Crop and Soil Environmental Sciences (ABSTRACT) Weathering products of primary minerals such as biotite can greatly influence soil properties and characteristics. Weathering of biotite supplies nutrients such as K+ and weathers into vermiculite/montmorillonite or kaolinite, which have varying influences on soil properties and characteristics. Various laboratory studies and field investigations have suggested that biotite weathers predominantly to kaolinite in the Piedmont of Virginia, and to vermiculite/montmorillonite in the Blue Ridge. This study was conducted to determine if the weathering mechanisms of biotite are controlled by temperature, or if other factors, such as vegetation or leaching intensity dominantly influence the weathering process. A column study investigation was conducted to assess the influence of different acids, simulated rainfall rates, surface horizons, and temperature on the weathering and cation release of biotite. A field investigation was also conducted on the clay mineral fraction of soils in Grayson County, VA formed above biotite granite. The soils were sampled at two elevational extremes to assess clay mineral weathering at the maximum climatic difference in the region. Leaching of columns packed with biotite with selected treatments of acids, surface horizons, leaching rates, and temperatures produced no detectable secondary weathering-products of biotite by x-ray diffraction (XRD). -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Political Aesthetic of Irony in the Post-Racial United States Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8fd7t1ph Author Jarvis, Michael Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Political Aesthetic of Irony in the Post-Racial United States A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Michael R. Jarvis March 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jennifer Doyle, Chairperson Dr. Sherryl Vint Dr. Keith Harris Copyright by Michael R. Jarvis 2018 The Dissertation of Michael R. Jarvis is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the support of my committee, Professors Jennifer Doyle, Sherryl Vint, and Keith Harris. Thank you for reading this pile of words, for your feedback, encouragement, and activism. I am not alone in feeling lucky to have had each of you in my life as a resource, mentor, critic, and advocate. Thank you for being models of how to be an academic without sacrificing your humanity, and for always having my back. A thousand times, thank you. Sincere thanks to the English Department administration, UCR’s Graduate Division, and especially former Dean Joe Childers, for making fellowship support available at a crucial moment in the writing process. I was only able to finish because of that intervention. Thank you to the friends near and far who have stuck with me through this chapter of my life.