1. Situation Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #2, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 December 7, 2018

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 DECEMBER 7, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Relief actor records at least 150 GBV cases in Bentiu during a 12-day period 5% 7% 20% UN records two aid worker deaths, 60 7 million 7% Estimated People in South humanitarian access incidents in October 10% Sudan Requiring Humanitarian USAID/FFP partner reaches 2.3 million Assistance 19% 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan – people with assistance in October December 2017 15% 17% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE 6.1 million Health (17%) Nutrition (15%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/FFP $402,253,743 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) September 2018 Shelter & Settlements (5%) 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $628,994,9784 2 million BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 Estimated IDPs in 84% 9% 5% South Sudan OCHA – November 8, 2018 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,760,121,951 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES 194,900 Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases KEY DEVELOPMENTS UNMISS – November 15, 2018 During a 12-day period in late November, non-governmental organization (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) recorded at least 150 gender-based violence (GBV) cases in Unity State’s Bentiu town, representing a significant increase from the approximately 2.2 million 100 GBV cases that MSF recorded in Bentiu between January and October. -

Enhancing People's Resilience in Northern Bahr El Ghazal, South

BRIEF / FEBRUARY 2021 Enhancing people’s resilience in Northern Bahr el Ghazal, South Sudan Northern Bahr el Ghazal, situated in the northern part The major sources of livelihoods in Northern Bahr el of South Sudan, is one of the country’s states that Ghazal are cattle rearing, small-scale agriculture and experiences fewer incidences of sub-national conflict, trade, especially in Aweil town – the capital of the state cattle raiding and revenge killings, and has experienced – and in the payams1 near to the border with Sudan. Due relatively less political violence than other states since to a long dry spell between May and July 2020, followed the eruption of civil war in South Sudan in December by heavy rains between July and September – which led 2013. to flooding in many of the state’s counties – low harvests and food insecurity are anticipated in 2021. The government of South Sudan increased the number of states in the country from ten to 32 between October Like their fellow citizens in other parts of the country, 2015 and February 2020. Northern Bahr el Ghazal was people in Northern Bahr el Ghazal are facing a dire split into two states (Aweil and Aweil East) and two of economic plight. Several factors have accentuated this its counties (Aweil North and Aweil South) were given to situation, including poor road network connections, Raja county in Western Bahr el Ghazal to form Lol state. the closure of the South Sudan-Sudan borders due to When the government reversed this decision in February disagreements over the border line, multiple taxation on 2020 and returned to the original ten states, Northern roads connecting the state to the country’s capital Juba, Bahr el Ghazal reverted to its former status. -

The Republic of South Sudan

INTEGRATED FOOD SECURITY PHASE CLASSIFICATION THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN KEY IPC FINDINGS: JANUARY-JULY 2017 The food security situation in South Sudan continues to deteriorate, with 4.9 million (about 42% of population) estimated to be severely food insecure (IPC Phases 3, 4, and 5), from February to April 2017. This is projected to increase to 5.5 million people, (47% of the national population) at the height of the 2017 lean season in July. The magnitude of these food insecure populations is unprecedented across all periods. In Greater Unity, some counties are classified in Famine or high likelihood/risk of Famine. In the absence of full quantitative data sets (food consumption, livelihoods changes, nutrition and mortality), analyses were complemented with professional judgment of the Global IPC Emergency Review Committee and South Sudan IPC Technical Working Group (SS IPC TWG) members. The available data are consistent with Phase 5 (Famine) classification and include available humanitarian assistance plans at the time of the analysis. In January 2017, Leer County was classified in Famine, Koch at elevated likelihood that Famine was happening and Mayendit had avoided Famine through delivery of humanitarian assistance. From February to July 2017, Leer and Mayendit are classified in Famine, while Koch is classified as Famine likely to happen. Panyijiar was in Phase 4 (Emergency) in January and is likely to avoid a Famine if the humanitarian assistance is delivered as planned from February to July 2017. With consistent, adequate, and timely humanitarian interventions, the Famine classification could be reversed with many lives saved. Acute malnutrition remains a major public health emergency in South Sudan. -

Amplifying People's Voices to Contribute to Peace and Resilience

BRIEF / MARCH 2021 Amplifying people’s voices to contribute to peace and resilience in Warrap, South Sudan Warrap state is in the northern part of South Sudan. The clans in the state were high. The governor toured Tonj state borders Unity state to the north-east, Lakes to the North, Tonj South and Gogrial East counties with peace east, Northern Bahr el Ghazal to the north and Western and reconciliation messages and pledged to work closely Bahr el Ghazal to the south. The state is home to the with peace actors in the state. However, violent conflicts Dinka and Bongo ethnic communities. among rival clans in Greater Tonj have intensified, leading to Bona Panek – who was seen as having a ‘soft’ approach The main sources of livelihoods for people in Warrap to communal conflict – being replaced by General Aleu include cattle rearing and small-scale farming, as well Ayieny on 28 January 2021. as beekeeping and wild honey harvesting among the Bongo community in Tonj South County. Cattle rearing Warrap, like many other parts of South Sudan, is is associated with numerous challenges such as cattle experiencing tough economic times. There are multiple raids, stealing, and the need to migrate to neighbouring factors at play, such as political instability in the state communities in search of food and for grazing lands and and in the country, poor road connections, persistent water for animals. In recent years, Warrap has experienced intercommunal violence, and hyperinflation compounded unprecedented intercommunal conflicts, violent cattle by a decline in the purchasing power of the South raiding fuelled by the proliferation of small arms and light Sudanese pound. -

Who Does What Where in Northern Bahr El Ghazal State (30 June 2014)

Who does What Where in Northern Bahr el Ghazal State (30 June 2014) Q d Q ASCDA, CES, CESVI, Concern, DRC, FAO, SP, SPEDP, l SUDAN d VSFS, Welthungerhilfe l ACF-USA, FAO, NRC, SP,Abyei VSFS Region HealtNetTPO f f IRC g g UNMAS à e Concern, IOM e ACF-USA, UNICEF ARC, IRC, NVP, SC, UNHCR, UNICEF, VSF-S Concern, MSF-Spain, UNICEF j ç IAS, SDC ARC, NVP, UNICEF, VSF-S j SDC ç Aweil North Q Aweil East Q UNICEF d Northern Bahr el Ghazal d CESVI, Concern, FAO, NRC, PIN, l ASCDA, AWODA, FAO, HeRYSS SPEDP, Welthungerhilfe l f IRC Concern f g g Aweil West e à à e IRC, UNICEF Warrap Concern, MC, UNICEF j UNICEF, VSF-S !! ARC, UNICEF, VSF-S, YES j ç OCHA SDC ç Aweil Centre Aweil South m Q d i WFP CORDAID, DRC, FAO, FLDA-SS, l SAADO, STO, VSFS, Welthungerhilfe f IRC Legend SUDAN g UNHAS Abyei Camp management Region Q à UNMAS SOUTH SUDAN ETHIOPIA m Coordination e Education MC, UNICEF CAR d Juba ! Emergency j ARARD, ARC, NRC, UNICEF, VSF-S KENYA i Telecommunication DRC ç UGANDA l Food security and livelihood f Health # of Organizations per county g Logistics No organization Mine action 1 - 2 organizations à NFI & Emergency Shelter Qdi fgà je çl 3 - 4 organizations e Western Bahr el Ghazal Aweil Centre 0 0 1 1 1 1 2 5 0 0 8 Nutrition 5 or more Aweil East 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 7 0 2 5 organizations Protection No organization j Aweil North 0 0 0 1 0 1 3 4 0 1 10 Aweil South 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 2 0 0 4 Not applicable WASH 30 km ç UNICEF, UNFPA and WHO have nationwide health projects Aweil West 0 1 0 1 0 0 2 4 0 1 7 Creation date: 19 June 2014. -

C the Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan

C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons (from State Ministries of Livestock and Fishery Industries and FAO South Sudan Office) for collecting field data from the sample counties in nine of the ten States of South Sudan: Angelo Kom Agoth; Makuak Chol; Andrea Adup Algoc; Isaac Malak Mading; Tongu James Mark; Sebit Taroyalla Moris; Isaac Odiho; James Chatt Moa; Samuel Ajiing Uguak; Samuel Dook; Rogina Acwil; Raja Awad; Simon Mayar; Deu Lueth Ader; Mayok Dau Wal and John Memur. The authors also extend their special thanks to Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor and Dr Abdal Monium Osman, Senior Programme Officer, at FAO South Sudan for initiating this study and providing the necessary support during the preparatory and field deployment phases. DISCLAIMER FAO South Sudan mobilized a team of independent consultants to conduct this study. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. COMPOSITION OF STUDY TEAM Yacob Aklilu Gebreyes (Team Leader) Gezu Bekele Lemma Luka Biong Deng Shaif Abdullahi i C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...I ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... VI NOTES .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Security Council Distr.: General 31 May 2012

United Nations S/2012/384 Security Council Distr.: General 31 May 2012 Original: English Letter dated 31 May 2012 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of South Sudan to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council As you are aware, the Republic of the Sudan has reported to the Security Council that it has withdrawn Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) from the Abyei Area. This has apparently been confirmed by the United Nations and was subsequently welcomed in a statement by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. I regret to inform you that SAF have not in fact withdrawn from Abyei. Rather, SAF troops have been redeployed as police officers within the Abyei Area. There are two platoons of SAF troops in police uniform in Abyei town; two platoons of SAF troops in police uniform in Langer (Goli), 22 km north of Abyei town; and two platoons of SAF troops in police uniform in Agany, 10 km north of Langer (Goli). The Sudan Armed Forces have also established a centre, west of Diffra, for various militias that are engaged in attacks in Northern Bahr-el-Ghazal State and in Abyei Area. It is our understanding that Major General Adam Mohamed is SAF commander in charge of all these forces deployed in the Abyei Area. The Sudan Armed Forces have also continued to launch ground attacks and aerial bombardments in Northern Bahr-el-Ghazal State. Furthermore, the Sudan continues to violate South Sudanese airspace by conducting flights over Western Bahr-el-Ghazal, Northern Bahr-el-Ghazal and Unity states, as well as Juba. -

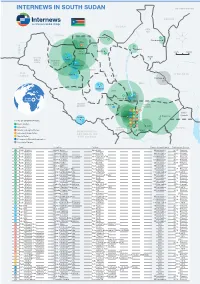

Internews in South Sudan Map Updated May 2020

INTERNEWS IN SOUTH SUDAN MAP UPDATED MAY 2020 SUDAN SUDAN UPPER NILE SUDAN Jamjang 11 3 Gendrassa Abyei 1 2 UNITY 34 Malakal 40 Bentiu 0 km 100 km Turalei 7 SUDAN 4 5 Nasir WESTERN Aweil BAHR EL NORTHERN GHAZAL BAHR EL 32 GHAZAL Kwajok WARRAP D.R. 41 Wau ETHIOPIA CONGO 42 Leer Pochala 36 JONGLEI 37 38 Rumbek LAKES 8 9 10 6 Bor South Awerial Sudan WESTERN Mundri EASTERN EQUATORIA 35 EQUATORIA 12 18 24 30 13 19 25 Ilemi- Kapoeta Dreieck Yambio Juba 14 20 26 15 21 27 31 TYPES OF ORGANIZATIONS 43 16 22 28 Radio Station 17 23 29 Torit Repeaters CENTRAL KENYA Media Training Institution EQUATORIA Magwi DEMOCRATIC 33 Advocacy Organization REPUBLIC OF Media Outlet THE CONGO Community-Based Organization UGANDA Associate Partner Type Location Partner Reach (if applicable) Partnership Active 1 Radio Station Abyei, Agok Abyei FM 60 km radius 2015 - Present 3 Radio Station Jamjang, Unity Jamjang FM 60 km radius 2016 - Pesent 4 Radio Station Aweil, Northern Bahr el Ghazal Akol Yam 91.0FM 150 km radius 2017 - Present 6 Radio Station Awerial, Lakes Mingkaman 100FM 150 km radius 2014 - Present 7 Radio Station Bentiu, Unity Kondial FM 30 km radius 2018 - Present 8 Radio Station Bor, Jonglei Radio Jonglei 50 km radius 2018 11 Radio Station Gendrassa, Upper Nile Radio Salam 30 km radius 2019 - Present 19 Radio Station Juba, Central Equatoria Radio Bakhita 100 km radius 2015-2016 23 Radio Station Juba, Central Equatoria Advance Youth Radio 50 km radius 2019 - Present 26 Radio Station Juba, Central Equatoria Eye Radio 60 km radius 2014 - Present 28 Radio Station -

Distribution of Ethnic Groups in Southern Sudan Exact Representationw Ohf Iteh En Isleituation Ins Tehnen Acrountry

Ethnic boundaries shown on this map are not an Distribution of Ethnic Groups in Southern Sudan exact representationW ohf iteh eN isleituation inS tehnen aCrountry. The administrative units and their names shown on this map do not imply White acceptance or recognition by the Government of Southern Sudan. Blue ") State Capitals This map aims only to support the work of the Humanitarian Community. Nile Renk Nile Sudan Renk Admin. Units County Level Southern Darfur Southern Shilluk Berta Admin. Units State Level Kordofan Manyo Berta Country Boundary Manyo Melut International Boundaries Shilluk Maban Sudan Fashoda Dinka (Abiliang) Abyei Pariang Upper Nile Burum Malakal Data Sources: National and State Dinka (Ruweng) ") boundaries based on Russian Sudan Malakal Baliet Abiemnhom Panyikang Map Series, 1:200k, 1970-ties. Rubkona Guit County Boundaries digitized based on Aweil North Statistical Yearbook 2009 Aweil East Twic Mayom ") Nuer (Jikany) Canal (Khor Fulus) Longochuk Southern Sudan Commission for Census, Dinka (Twic WS) Nuer (Bul) Statistics and Evaluation - SSCCSE. Fangak Dinka (Padeng) Digitized by IMU OCHA Southern Sudan Aweil West Dinka (Malual) Nuer (Lek) Gogrial East Unity Nuer (Jikany) Northern Bahr el Ghazal ") Luakpiny/Nasir Aweil Maiwut Aweil South Raga Koch Gogrial West Nuer (Jegai) Nyirol Ulang Nuer (Gawaar) Aweil Centre Warrap ") Tonj North Ayod Kwajok Mayendit Leer Dinka (Rek) Fertit Chad Nuer (Adok) Nuer (Lou) Jur Chol Tonj East ") Wau Akobo Western Bahr el Ghazal Nuer (Nyong) Dinka (Hol) Uror Duk Jur River Rumbek North Panyijar -

Greater Bahr El Ghazal, South Sudan July - September 2018

Situation Overview: Greater Bahr el Ghazal, South Sudan July - September 2018 Introduction. Map 1: REACH assessment coverage of the GBeG region, July (A), August (B) and September 2018 (C) C Continued conflict, displacement and A B environmental shocks negatively impacted access to food and restricted the ability for communities to meet basic needs in Greater Bahr el Ghazal (GBeG) between July and September 2018. Waves of displacement 0 - 4.9% in Western Bahr el Ghazal (WBeG) and 5 - 10% flooding in Northern Bahr el Ghazal (NBeG), 11 - 20% WBeG and Greater Tonj area1 (GTA) 21 - 50% threatened overall food security in the region. 51 - 100% Assessed settlement dynamics across the GBeG region from July in WBeG and NBeG states reporting the REACH has been assessing hard-to-reach to September 2018. The first section analyses presence of IDPs increased during the areas in WBeG since April 2017, NBeG since 742 settlements in 11 counties in the GBeG displacement and population movement and assessment period, whereas GTA saw a March 2018 and GTA since January 2018. region. To ensure an up to date understanding the second section focuses on access to food decrease in assessed settlements reporting The data was collected through key informant of current displacement dynamics and and basic services for both internally displaced IDPs living in the community, from 60% interviews on a monthly basis from settlements humanitarian conditions in settlements across WBeG State, NBeG State and GTA, REACH persons (IDPs) and local populations in Figure 1: Proportion of assessed settlements in Jur River, Wau, and Raja counties in WBeG assessed settlements in the GBeG region. -

Politics, Power and Chiefship in Famine and War a Study Of

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT POLITICS, POWER AND CHIEFSHIP IN FAMINE AND WAR A STUDY OF THE FORMER NORTHERN BAHR el-ghazal STATE, SOUTH SUDAN RIfT vAllEY INSTITUTE SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities Politics, power and chiefship in famine and war A study of the former Northern Bahr el-Ghazal state, South Sudan NICKI KINDERSLEY Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHOR Nicki Kindersley is a historian of the Sudans. She is currently Harry F. Guggenheim Research Fellow at Pembroke College, Cambridge University, and a Director of Studies on the RVI Sudan and South Sudan Course. THE RESEARCH TEAM The research was designed and conducted with co-researcher Joseph Diing Majok and research assistant Paulino Dhieu Tem. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES (SSCA) PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH & COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PROGRAMME MANAGER: Tymon Kiepe EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-54-8 COVER: A chiefs’ meeting in Malualkon in Aweil East, South Sudan. RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2017 Cover image © Nicki Kindersley Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers.