Knitting After Making What We Do with What We Make

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Small Seeds Bigtreesgrow

YMSO14Cover.REVISE:Layout 1 9/4/14 12:10 PM Page 1 September/October 2014 From Small Seeds BigTreesGrow FREE COPY YMN1014-Namaste.indd 1 04/08/2014 11:33 AM Shown –Fietelberg, Mount Antero, Caroline Peak, and Santa Isabel in Schachenmayr Bravo Big Color Distributor of Rowan, Schachenmayr, My Mountain, Regia, Lopi, James C. Brett, Butterfl y Super 10 Cotton 800 445-9276 US • 800 263-2354 Canada YMN1014-Westminster_REV.indd 1 8/20/14 2:49 PM 02_YMSO14EdLetter.FINAL:Layout 1 9/4/14 11:52 AM Page 2 Editor’s Letter Inspired ROSE CALLAHAN I get most of my best ideas while at the Yarn Market News Smart Business Conference. Or in the shower, but mostly at the conference. Even though the sessions we schedule focus on small businesses, particularly small retail businesses, there’s so much for me to learn as well— not just ways to help educate my readers, but also to help Yarn Market News and aspects of my own personal life. Branding, negotiating, trends—all of these things come into play. IStore owners who attend the conference tell me it changes their perspective on just about everything. The people who attend year after year keep coming back for that very reason (and it’s a point of pride for us, too). In an atmosphere of support and openness, we can discuss obstacles and challenges, share thoughts and ideas and so much more. Early next year we will return to Seattle for our annual meeting of the minds. A recurring “theme” for the shows has been “how to be successful in a changing economy.” We know it’s tough out there for all business owners. -

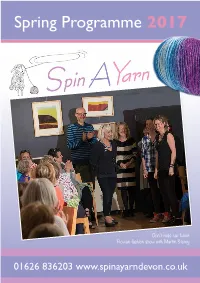

Spring Programme 2017

Spring Programme 2017 Don’t miss our latest Rowan fashion show with Martin Storey 01626 836203 www.spinayarndevon.co.uk 1 Spring 17_Layout 1 17/11/2016 12:05 Page 1 BOOK 705 THE ELEVENTH SUBLIME EXTRA FINE MERINO DK BOOK 18 designs for women www.sublimeyarns.com t +44 (0)1924 369666 e [email protected] The Sublime Knitting Helpline: +44 (0)1924 231686 2 Telephone: 01626 836203 www.spinayarndevon.co.uk SPRING NEWSLETTER 2017 Dear Friends Address: 26 Fore Street While writing this newsletter in November, Bovey Tracey, Devon TQ13 9AD the skies are blue and the trees are Telephone: 01626 836 203 looking glorious in shades of red and www.spinayarndevon.co.uk bronze. Hope that this is a good omen [email protected] for the winter and that Christmas is dry, sunny and cold, a perfect time to enjoy our beautiful winter knits. SPIN A YARN FASHION SHOW – 21 FEBRUARY First exciting news is that Martin Storey is to host another Fashion Show for Spin A Yarn at the Devon Guild of Craftsmen on Tuesday, 21 February 2017. This will start as usual at 6.00pm with a welcome drink, followed by a full evening meal and fashion show. In addition to Rowan samples Martin will be bringing along samples from three of his recent books, More Fairisle Knits, Scandinavian Knits and Afghan Knits. WORKSHOPS We are very excited about our Spring/ Summer schedule as we have lots of new workshops for you. These include Brioche Knitting and Celtic Cables with Claire Crompton and Orenburg and Shetland shawl workshops with Anniken while Alison Crowther Smith is teaching us how to make the most of Kidsilk Haze and similar yarns. -

Addicted to Ball and Club Juggling

Addicted to Ball and Club Juggling -A guide to improve your juggling- Addicted to Ball and Club Juggling Book 1: Two hands 2 Preface................................................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Structure of the book ............................................................................. Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Part 1: A juggling course...................................................Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Topic 1: General stuff ........................................................Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. General working advise.......................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Practical training advise ......................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Advise on buying and using juggling props........................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Conventions ........................................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Games .................................................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Topic 2: Enlarge your skill, improve your technique .....Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. Training advise ..................................................................................... Fout! Bladwijzer niet gedefinieerd. -

Knitting in Australia: Artefact & Exegesis

1 Knitting in Australia: artefact & exegesis Sue Green Approved for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne University of Technology August, 2018 2 3 Abstract This project, undertaken by artefact and exegesis, draws together a book about knitting in Australia intended for a general readership, with a scholarly framework. The exegesis arises from issues identified in producing the artefact, an interview-based, non-fiction publication, Disruptive knitting: how knitters are changing the world. Its nine themed chapters are created through autoethnographic, Practice-Led Research based on reporting and interpreting 87 interviewers with knitters and related interviewees. This includes their knittings’ relevance to key social issues such gender, women’s role and social inequality. It enriches the discussion of how, for many, knitting has become a tool for rebellion, art making and activism on feminist and political issues. It examines and demonstrate knitting’s ability not only to reflect the wider Australian society, but to influence that society through both individual and collective acts of knitting in the context of the gendered nature of the craft. Central to this artefact production and its exegetical framework are two complementary questions: How has the traditional craft of knitting, stereotypically a woman’s hobby for the purpose of producing utilitarian items including garments, evolved to become a tool for numerous other purposes including political protest, reinforcement of and rebellion against traditional gender roles, and the creation of fine art? What does the practice of knitting reveal about Australian society and how has it influenced events in that society since World War II? This project brings together insights into creative work that has largely been isolated as women’s craft, created by labour regarded as having no calculable value. -

Rubin Named Superintendent for Cranford Schools at $165,000 DWC

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, March 30, 2017 OUR 127th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 13-2017 Periodical – Postage Paid at Rahway, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] ONE DOLLAR DWC OKs Grants, Discusses Girls Day, Night Out By DOMINIC A. LAGANO The board receives recommenda- DWC Executive Director Sherry Specially Written for The Westfield Leader tions from its Design Committee, Cronin. “They started with having WESTFIELD — The Downtown which works with business and prop- rock and roll players come and per- Westfield Corporation (DWC) board erty owners to ensure that the busi- form in their space and it developed a of directors, the management entity ness in question adheres to Westfield’s cult following among rock and roll of the Special Improvement District ordinances regarding signage and the bands.” (SID), at its Monday night approved like. The board also approved a grant grants for two businesses opening The board first approved a grant for Hand Picks, a clothing store that soon in the downtown area. for Emack & Bolio, a shop to be will be located at 107 Prospect Street. As part of its mandate, the DWC located at 258 East Broad Street that “I don’t know if you’ve been watch- provides grants to businesses that will feature “ice cream for the con- ing Facebook, but kids have been improve the exterior façades of their noisseur.” nuts about this place. They sell urban buildings, which usually occurs when “The first grant is for Emack and wear,” stated Ms. -

The Little Book of the Cultural Hijacker

The Little Book of the Cultural Hijacker Towards Critical Action Graphic Design Stefania Passera 1 the little book of the cultural hijacker - towards critical action graphic design Master of Arts Thesis Aalto University School of Art and Design Department of Media Master Programme in Graphic Design Printed in Aalto University School of Art and Design, Helsinki Binded at Kirjansitomo Jokinen, Helsinki Papers: Colorit 120g, Munken Lynx 120g Font: Archer Spring 2011, Helsinki 2 3 Index iv index 1 introduction 11 chapter 1 Soita Mummolle A prototype for low-budget social campaigns. 12 1. The idea 14 2. Conditions of the experiment 16 3. Timeline of the campaign and planning 18 4. Marketing tools 18 4.1. Blog 20 4.2. Social media (Facebook, Twitter, Flickr) 23 4.3. Survey 24 4.4. Street Actions 26 4.5. Knit Guerrilla 29 4.6. Billposting 30 4.7. Flash mob 32 4.8 PR 33 5. Evaluation 36 6. Beyond the case study 36 6.1. Prototyping as a trigger for innovative communication strategies 42 6.2. The online/offline dialectic 44 6.3. Design techniques, appropriation, focus on media iv 46 6.4. Female participation and the do-it-yourself attitude 49 7. Design case studies for comparison 49 7.1. Carrotmob: crowdsourced good-doing 52 7.2. Buy Nothing Day: use the media against themselves 54 7.3. Improv Everywhere VS. Bill2: different implementations of the flash mob format 57 7.4. Novita sponsors guerrilla knitting in Kallio, Helsinki: companies' new way to speak to their potential customers 59 7.5. -

January 2014

January 2014 Get in Gear or te New Year FREE COPY Editor’s Letter Business Minded ROSE CALLAHAN One of my favorite weekends of the year is the one spent at the Yarn Market News Smart Business Conference. The name of the conference is long and solidly describes what it is, but let’s be honest: It’s a little boring. It doesn’t get across just how fun and special this event actually is. When I tell people outside our industry why I’m unavailable that weekend, they give me a sympathetic look, for in their fields “professional development” is a tedious affair. But in our case, that’s not true at all. I’m quick to explain not only why I like going to the conference so much, but why it’s so important to the industry. The atmosphere is warm, Ofriendly and open, but it’s educational and inspiring as well. We’re there for serious work—the state of our economy is, after all, no laughing matter—but that doesn’t mean we can’t have some fun while we do it. Something that strikes me every year is how noncompetitive every- one is while they’re together. People with shops in the same general area commiserate about a problem customer, a local law that affects their businesses, the vagaries of the recent weather. Those who are meeting for the first time set up regular phone calls to talk shop once they’re back home. Owners who’ve been in business for decades regularly (and eagerly) share on our cover tips—handling vendors, for instance—with LYSOs who’ve been open for less than a year. -

A Craft Makes a Comeback

by Phyllis McIntosh A Craft Makes a Comeback The joy of “making a piece of string into something I can wear,” as one knitter described it, has catapulted the ancient craft of hand knitting into one of the most popular hobbies in the United States. Once considered the province of grannies and expectant mothers stitching layettes, knitting is enjoying a 21st century resurgence, espe- cially among young people. Knitting, it turns out, is a trendy, often eco-friendly pastime with a wide range of appeals. And, thanks to the Internet, modern knitters can share knowledge and ideas through vir- tual knitting circles that span the nation and even the globe. 36 2 0 1 1 N u m b e r 1 | E n g l i s h T E a c h i n g F o r u m History of Knitting 20th century, rejected by one generation as too old-fashioned for the modern woman Historians believe that knitting origi- and embraced by the next as a fun, even nated in the Middle East and spread to trendy, pastime. Some swings in popularity Europe, via trade routes, and eventually were dictated by history. During the Great to the western world as European immi- Depression of the 1930s, for example, grants settled there. The oldest known many women turned to knitting out of items of knitted fabric are socks dating economic necessity. In wartime, Americans from the 3rd to 5th century, excavated in answered the patriotic call to knit socks, Egypt during the 1800s. Likely created sweaters, scarves, mittens, and stretch ban- with a single needle, they closely resemble dages for soldiers on the battlefront. -

Feb 2017 Newsletter What the Knit! a 501(C)(3) Corporation PO Box 21594, Bakersfield , CA 93390

Feb 2017 Newsletter What the Knit! A 501(c)(3) corporation PO Box 21594, Bakersfield , CA 93390 Guild Meeting Saturday February 11th, 2017 Executive Board Members President - Suzanne Bryan 9:00 AM to Noon at the Kern Co. [email protected] Supt. of Schools Bldg. at Vice President - Katherine Birkbeck th 1300 17 Street, Room 1A [email protected] Free parking in structure Treasurer - Jacki Rickels accessible from 18th Street [email protected] Secretary - Renee Petrowsky Plan for an informal "social knit" during [email protected] the last hour of the guild meeting. Parliamentarian - Cathy Henry We're going to break into groups to At Large - Amy St Amour give some hands-on individual At Large - Sharon Wainwright ************************* assistance. Bring something to knit. Committee Chairs OR Bring a project you're "stuck" on ✴ Program - Suzanne Bryan and get hands on help from an ✴ Fair Coordinator - Janie Reiland experienced knitter. OR Bring your i-Pad ✴ Greeter - Sharon Wainwright or similar device used for . Ravelry ✴ Hospitality Committee - Linda Neel Also bring donation yarn, needles, and ✴ Librarian - Barbara Norman - accessories to this guild meeting. We [email protected] collect and donate it to the high school ✴ Membership Committee - Cindy librarians who have yarn clubs. The McBride students will appreciate it. Bring items ✴ Newsletter - Claire Christian you have either lost interest in or have ✴ Pay It Forward Committee - Pam too much or too many of (i.e. stitch Neufeld markers). ✴ Retreat Committee - Kate Birkbeck, Cindy McBride & Linda Neel Keep in mind that the raffled items ✴ Focused Sponsorships - Cathy Henry at the monthly guild meetings also ✴ Sunshine - April Cox come from your donations. -

N Sisteemteoretiese Kartering Van Die Afrikaanse Literatuur Vir Die Tydperk 2000–2009: Kanonisering in Die Afrikaanse Literatuur

’n Sisteemteoretiese kartering van die Afrikaanse literatuur vir die tydperk 2000–2009: Kanonisering in die Afrikaanse literatuur A.J.T. (LETI) KLEYN Voorgelê ter vervulling van die vereistes vir die graad Philosophiae Doctor (Uitgewerswese) in die Fakulteit Ingenieurswese, Bou-omgewing en Inligtingtegnologie Universiteit van Pretoria Pretoria Studieleiers: prof. Maritha Snyman (Departement Inligtingkunde) prof. Henning Pieterse (Kreatiewe Skryfkuns/Departement Afrikaans) Universiteit van Pretoria 20 Mei 2013 © University of Pretoria Verklaring Ek verklaar dat “’n Sisteemteoretiese kartering van die Afrikaanse literatuur vir die tydperk 2000–2009: Kanonisering in die Afrikaanse literatuur:” my eie werk is in die ontwerp en uitvoering daarvan, dat dit nie voorheen vir enige graad- of eksamendoeleindes aan hierdie, of enige ander universiteit voorgelê is nie en dat alle bronne wat gebruik is, voldoende aangedui en erken is deur volledige bibliografiese verwysings. Declaration I declare that “’n Sisteemteoretiese kartering van die Afrikaanse literatuur vir die tydperk 2000– 2009: Kanonisering in die Afrikaanse literatuur” is my own work in design and execution, that it has not been submitted for any degree or examination at this or any other university, and that all the sources used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by complete reference. A.J.T. (Leti) Kleyn Geteken/signed ___________________ Datum/date ______________________ © University of Pretoria Opsomming In hierdie studie word ondersoek ingestel na die rolspelers in die -

A Craft Makes a Comeback

by Phyllis McIntosh A Craft Makes a Comeback The joy of “making a piece of string into something I can wear,” as one knitter described it, has catapulted the ancient craft of hand knitting into one of the most popular hobbies in the United States. Once considered the province of grannies and expectant mothers stitching layettes, knitting is enjoying a 21st century resurgence, espe- cially among young people. Knitting, it turns out, is a trendy, often eco-friendly pastime with a wide range of appeals. And, thanks to the Internet, modern knitters can share knowledge and ideas through vir- tual knitting circles that span the nation and even the globe. 36 2 0 1 1 N UMBER 1 | ENGLISH TEACHING FORUM History of Knitting 20th century, rejected by one generation as too old-fashioned for the modern woman Historians believe that knitting origi- and embraced by the next as a fun, even nated in the Middle East and spread to trendy, pastime. Some swings in popularity Europe, via trade routes, and eventually were dictated by history. During the Great to the western world as European immi- Depression of the 1930s, for example, grants settled there. The oldest known many women turned to knitting out of items of knitted fabric are socks dating economic necessity. In wartime, Americans from the 3rd to 5th century, excavated in answered the patriotic call to knit socks, Egypt during the 1800s. Likely created sweaters, scarves, mittens, and stretch ban- with a single needle, they closely resemble dages for soldiers on the battlefront. modern knits. The oldest surviving exam- During World War II, the American ples of true knitting, using the two-needle Red Cross supplied patterns for military method popular today, are blue and white wear that were shared among knitters, cotton socks, again from Egypt, that were many of whom produced the same items fabricated somewhere between the 11th over and over so they could memorize and the 14th centuries. -

Athabasca University APRJ-699 Hand Knitting Yarn Industry with Reference to Unique Sources of Supply from Canada

Athabasca University APRJ-699 Hand Knitting Yarn Industry with Reference to Unique Sources of Supply from Canada. Prepared By: Igor Pustylnick Coach: Lucien Cortis Date: 04/08/2006 Word Count: 15520 Executive Summary ..............................................................................................4 Introduction ...........................................................................................................7 Goals of Research ................................................................................................8 Industry Composition ............................................................................................9 Sources of Fiber..............................................................................................10 Industrial Fiber Growers...............................................................................10 Small Fiber Growers ....................................................................................12 Artificial Fiber Manufacturers .......................................................................12 Commodity Traders.........................................................................................13 Yarn Mills.........................................................................................................13 Cottage Mills................................................................................................13 Yarn Designers................................................................................................14 Yarn Distributors..............................................................................................14