The Gothicization of the Harry Potter Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolkien's Women: the Medieval Modern in the Lord of the Rings

Tolkien’s Women: The Medieval Modern in The Lord of the Rings Jon Michael Darga Tolkien’s Women: The Medieval Modern in The Lord of the Rings by Jon Michael Darga A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2014 © 2014 Jon Michael Darga For my cohort, for the support and for the laughter Acknowledgements My thanks go, first and foremost, to my advisor Andrea Zemgulys. She took a risk agreeing to work with a student she had never met on a book she had no academic experience in, and in doing so she gave me the opportunity of my undergraduate career. Andrea knew exactly when to provide her input and when it was best to prod and encourage me and then step out of the way; yet she was always there if I needed her, and every book that she recommended opened up a significant new argument that changed my thesis for the better. The independence and guidance she gave me has resulted in a project I am so, so proud of, and so grateful to her for. I feel so lucky to have had an advisor who could make me laugh while telling me how badly my thesis needed work, who didn’t judge me when I came to her sleep-deprived or couldn’t express myself, and who shared my passion through her willingness to join and guide me on this ride. Her constant encouragement kept me going. I also owe a distinct debt of gratitude to Gillian White, who led my cohort during the fall semester. -

Read Book Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Kindle

HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY HALLOWS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. K. Rowling | 640 pages | 16 Oct 2014 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408855713 | English | London, United Kingdom Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows PDF Book And it seems the trio is finally on track, going to Luna Lovegood's place, seeing her room which is heartbreaking and hearing the Tale of the Three Brothers and the Deathly Hallows — a wand, an invisibility cloak, and a resurrection stone. Several characters -- mostly recurring supporting players, but also a couple of newly introduced ones -- are killed, mostly via the Killing Curse. The tragedy of Snape's tortured life comes to an end. Live, From New York! And breaking into Gringott's? Go ahead. In Chapter 1 Voldemort uses the killing curse on muggle studies professor Burbage. But because Rickman knew, he told everyone else on set that it absolutely wasn't the case. These aren't three kids any more: They're a year-old hero and his best friends, willing to give up everything to save the wizarding world. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows came out a month after I'd turned They go to Godric's Hollow on Christmas and for the first time Harry sees his parents' grave, plus a magical statue dedicated to them that only wizards can see. Shacklebolt, in the form of a lynx, appears at Bill and Fleur's wedding reception. There are no Quidditch matches in the final novel. The insults "Mudblood" and "blood traitor" -- which are the wizarding world's equivalent of nasty racist terms -- are said several times as well. -

SWR2 RADIOPHON, 4. Juli 2019, 21:03 Uhr Musikcollagen Zum Unabhängigkeitstag Von Gaby Beinhorn

1 SWR2 RADIOPHON, 4. Juli 2019, 21:03 Uhr Musikcollagen zum Unabhängigkeitstag Von Gaby Beinhorn Portal öffnen und schließen Claude Debussy: Nr. 11: La danse de Puck Michael Kiedaischs Debussy Projekt ZeytmusikEdition (57545) ZME017-1; 04 00.06.38 Großes Feuerwerk Claude Debussy: Feux d'artifice. Prélude Nr. 12 Christoph Delz (Klavier) Eigenproduktion Fontes Rocha: Das Feuerwerk Mísia Ensemble CD-Titel: Drama box TROPICAL MUSIC; 68.850 Rufus Wainwright: Les feux d'artifice t'appellent CD-Titel: All days are nights: Songs for Lulu Emarcy Records 00699 George Antheil: Ausschnitt aus Fireworks and the Profane Waltzes, für Klavier Jorge Zulueta (Klavier) eigenproduktion Bonustrack: Feuerwerk Igor Strawinsky: Feu d'artifice, op. 4 SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg; Leitung: Sylvain Cambreling Eigenproduktion N. N.: Babbachichuija Tom Waits CD: Orbitones, spoon harps & bellowphones – Experimental musical instruments ELLIPSIS ARTS, 3610 Barbara Bucholz: Ay ne ne (Russian Gypsy Song) Barbara Buchholz; Victoria Perskaya (voc) CD: Theremin: Russia with love 2 Intuition Records; 3382-2 Ann Lennox; David A. Stewart: Sweet dreams (are made of this) Marilyn Manson CD: Lest we forget - The best of (Marilyn Manson) Interscope 9863978 John Adams: Tromba lontana Glenn Fschthal, Laurie McGaw (Trompete) San Francisco Symphony, Edo de Waart The chairman dances, 2 Fanfares u.a. Nonseuch, 979144-2 Nr. 8: Liberté Francis Poulenc: Figure humaine, Kantate EuropaChorAkademie, Sylvain Cambreling CD: Chormusik des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vol.2 Glor, GCO9211 Michael Kiedaisch (1962-) 00.02.02 Mike Svoboda, Matthias Stich, Doesika Van der Linden: Mon coeur resigné Michael Kiedaischs Debussy Projekt ZeytmusikEdition ZME017-1 Großes Feuerwerk Agostino Steffani: La libertà contenta – Die zufriedengestellte Freiheit. -

Download Book / the Bonnie Wright Handbook

EJ4HDZNNTW3U < Kindle ~ The Bonnie Wright Handbook - Everything You Need to Know about Bonnie... The Bonnie Wright Handbook - Everything You Need to Know about Bonnie Wright Filesize: 6.05 MB Reviews It is great and fantastic. I actually have read and so i am certain that i am going to going to go through once again yet again in the future. I realized this ebook from my dad and i encouraged this book to find out. (Dr. Kayden Gerlach) DISCLAIMER | DMCA AQADCGPRXRUT \\ Kindle < The Bonnie Wright Handbook - Everything You Need to Know about Bonnie... THE BONNIE WRIGHT HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT BONNIE WRIGHT To read The Bonnie Wright Handbook - Everything You Need to Know about Bonnie Wright PDF, please refer to the button below and download the file or have access to other information which might be relevant to THE BONNIE WRIGHT HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT BONNIE WRIGHT book. Tebbo. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 146 pages. Dimensions: 11.9in. x 8.4in. x 0.4in.Bonnie Francesca Wright (born 17 February 1991) is an English actress, fashion model, screenwriter, director and producer. She is best known for playing Ginny Weasley in the Harry Potter film series. This book is your ultimate resource for Bonnie Wright. Here you will find the most up-to-date information, photos, and much more. In easy to read chapters, with extensive references and links to get you to know all there is to know about Bonnie Wrights Early life, Career and Personal life right away. A quick look inside: Bonnie Wright, Agatha Christie, Agatha Christie: A Life in Pictures, Evanna Lynch, Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (video game), Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (film), Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (video game), King Alfred School, London, London College of Communication, Matthew Lewis (actor), Rupert Grint, The Replacements (TV series), The Wizarding World of Harry Potter (Islands of Adventure), Tom Felton, University of the Arts London, Wright 128. -

Leadership Role Models in Fairy Tales-Using the Example of Folk Art

Review of European Studies; Vol. 5, No. 5; 2013 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Leadership Role Models in Fairy Tales - Using the Example of Folk Art and Fairy Tales, and Novels Especially in Cross-Cultural Comparison: German, Russian and Romanian Fairy Tales Maria Bostenaru Dan1, 2& Michael Kauffmann3 1 Urban and Landscape Design Department, “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism, Bucharest, Romania 2 Marie Curie Fellows Association, Brussels, Belgium 3 Formerly Graduate Research Network “Natural Disasters”, University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Correspondence: Maria Bostenaru Dan, Urban and Landscape Design Department, “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism, Bucharest 010014, Romania. Tel: 40-21-3077-180. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 11, 2013 Accepted: September 20, 2013 Online Published: October 11, 2013 doi:10.5539/res.v5n5p59 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v5n5p59 Abstract In search of role models for leadership, this article deals with leadership figures in fairy tales. The focus is on leadership and female domination pictures. Just as the role of kings and princes, the role of their female hero is defined. There are strong and weak women, but by a special interest in the contribution is the development of the last of the first to power versus strength. Leadership means to deal with one's own person, 'self-rule, then, of rulers'. In fairy tales, we find different styles of leadership and management tools. As properties of the good boss is praised in particular the decision-making and less the organizational skills. -

Defining Fantasy

1 DEFINING FANTASY by Steven S. Long This article is my take on what makes a story Fantasy, the major elements that tend to appear in Fantasy, and perhaps most importantly what the different subgenres of Fantasy are (and what distinguishes them). I’ve adapted it from Chapter One of my book Fantasy Hero, available from Hero Games at www.herogames.com, by eliminating or changing most (but not all) references to gaming and gamers. My insights on Fantasy may not be new or revelatory, but hopefully they at least establish a common ground for discussion. I often find that when people talk about Fantasy they run into trouble right away because they don’t define their terms. A person will use the term “Swords and Sorcery” or “Epic Fantasy” without explaining what he means by that. Since other people may interpret those terms differently, this leads to confusion on the part of the reader, misunderstandings, and all sorts of other frustrating nonsense. So I’m going to define my terms right off the bat. When I say a story is a Swords and Sorcery story, you can be sure that it falls within the general definitions and tropes discussed below. The same goes for Epic Fantasy or any other type of Fantasy tale. Please note that my goal here isn’t necessarily to persuade anyone to agree with me — I hope you will, but that’s not the point. What I call “Epic Fantasy” you may refer to as “Heroic Fantasy” or “Quest Fantasy” or “High Fantasy.” I don’t really care. -

Dumbledores Army Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix for String Quartet Nicholas Hooper Score and Parts Sheet Music

Dumbledores Army Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix For String Quartet Nicholas Hooper Score And Parts Sheet Music Download dumbledores army harry potter and the order of the phoenix for string quartet nicholas hooper score and parts sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of dumbledores army harry potter and the order of the phoenix for string quartet nicholas hooper score and parts sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 5105 times and last read at 2021-09-24 11:11:40. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of dumbledores army harry potter and the order of the phoenix for string quartet nicholas hooper score and parts you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Cello, Viola, Violin Ensemble: String Quartet Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Fireworks Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix For String Quartet Nicholas Hooper Score And Parts Fireworks Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix For String Quartet Nicholas Hooper Score And Parts sheet music has been read 4357 times. Fireworks harry potter and the order of the phoenix for string quartet nicholas hooper score and parts arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 16:44:52. [ Read More ] Fireworks Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix Nicholas Hooper For String Quartet Full Score And Parts Fireworks Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix Nicholas Hooper For String Quartet Full Score And Parts sheet music has been read 15280 times. -

Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy Kimberly Wickham University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Wickham, Kimberly, "Questing Feminism: Narrative Tensions and Magical Women in Modern Fantasy" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 716. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/716 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUESTING FEMINISM: NARRATIVE TENSIONS AND MAGICAL WOMEN IN MODERN FANTASY BY KIMBERLY WICKHAM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF KIMBERLY WICKHAM APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Carolyn Betensky Robert Widell Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 Abstract Works of Epic Fantasy often have the reputation of being formulaic, conservative works that simply replicate the same tired story lines and characters over and over. This assumption prevents Epic Fantasy works from achieving wide critical acceptance resulting in an under-analyzed and under-appreciated genre of literature. While some early works do follow the same narrative path as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Epic Fantasy has long challenged and reworked these narratives and character tropes. That many works of Epic Fantasy choose replicate the patriarchal structures found in our world is disappointing, but it is not an inherent feature of the genre. -

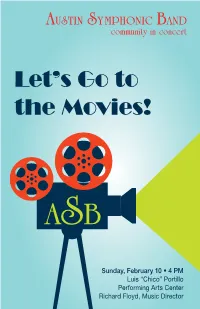

Download a PDF of the Concert Program

AUSTIN SYMPHONIC BAND community in concert Let’s Go to the Movies! Sunday, February 10 • 4 PM Luis “Chico” Portillo Performing Arts Center Richard Floyd, Music Director ASB Board of Directors and Officers Richard Floyd, Music Director Music Director: Richard Floyd Richard Floyd is in his 57th year of active involvement as Assistant Music Director: Bill Haehnel a conductor, music educator, and administrator. He has enjoyed Executive Director: Amanda Pierce a distinguished and highly successful career at virtually every level of wind band performance from beginning band programs President: Bryan Chin-Foon through high school and university wind ensembles as well as Past-President: Marty Legé adult community bands. Floyd recently retired as State Director of President-Elect: Kristin Morris Music at UT/Austin. He now holds the title Texas State Director of Music Emeritus. He has served as Music Director and Conductor Board of Directors: of the Austin Symphonic Band since 1985. Betsy Appleton Floyd is a recognized authority on conducting, the art of wind band rehearsing, con- John Bodnar cert band repertoire, and music advocacy. As such, he has toured extensively through- Tim DeFries out the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe as a clinician, adjudicator, and Clif Jones conductor including appearances in 42 American states and in nine other countries. In 2002 he was the single recipient of the prestigious A.A. Harding Award pre- Treasurer: Sharon Kojzarek sented by the American School Band Directors Association. The Texas Bandmasters Secretary: Kyndra Cullen Association named him Texas Bandmaster of the Year in 2006 and also recognized Bookkeeper: Mark Knight him with the TBA Lifetime Administrative Achievement Award in 2008 and the TBA Librarian: Karen VanHooser Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015. -

Fantasy As a Popular Genre in the Works of J. R. R. Tolkien and J. K

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Tereza Havířová FantasyasaPopularGenreintheWorksofJ.R.R.Tolkien andJ.K.Rowling Masters’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. Brno 2007 Ideclare thatIhaveworkedonthis dissertationindependently,usingonlythesources listedinthe bibliography. ……………………………. 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his time, patienceandadvice. I wouldalso like tosay‘thanks’ tomyeternal source of inspiration,my darktwin, theonlyreaderofFW,andthereal Draco. 3 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ....................................................................................................................................3 TABLE OF CONTENTS .....................................................................................................................................4 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................5 2 GENRE .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 3 FORMULAIC LITERATURE .................................................................................................................. 11 3.1 DEFINITION ............................................................................................................................................ 11 4 ROMANCE -

4 in 650: by Ned Kleiner an Interview with Asma, at About Ten O’Clock on Tues- Dr

Drama Preview: As You Like It -See Page 4- The Greylock Echo Monday, November 9th Mount Greylock RHS Williamstown, Mass MAJOR ADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES DUE FOR NEXT YEAR 4 in 650: By NED KLEINER An interview with Asma, At about ten o’clock on Tues- Dr. Rose Ellis, who had already a success, facilitating new curric- day, October 20th, Carrie Greene served as the WES superintendent ular alignment and shared teacher Salma, Seema, and stood up in front of the Mt. Grey- for a number of years. The move, development resources. Carrie lock School Committee to talk however, turned out largely to be Greene, a first-year member of Naseema about the future of the high the Mount Greylock School school. At the end of this Committee, suggested that By CATE COSTLEY year, Dr. Travis’s contract Mt. Greylock follow the el- will expire, and he has in- ementary schools’ example. dicated that he is interested Until Greene’s an- in retiring. Greene was sup- nouncement at the School posed to report on how the Committee meeting, a differ- school should go about find- ent outcome seemed likely. ing his replacement. To the The Massachusetts Depart- surprise of the committee, ment of Education supports Greene, who had spent more “Regionalization,” in which than thirty hours interview- the Northern Berkshire high ing town and state officials, schools (Drury, Hoosac, and recommended that Mt. Mt. Greylock) would com- Greylock join Superinten- bine into one super-region. dency Union 71. David Archibald, the chair On July 1, 2008, the ad- of the School Committee, ministrations at William- outlined one of the benefits stown and Lanesborough of regionalization to me: “if Elementary Schools joined you need a hundred thousand to create Union 71. -

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince™ (B

LIVE AT POWELL HALL Friday, October 25, 2019, at 7:00PM Saturday, October 26, 2019, at 7:00PM Norman Huynh, conductor Sunday, October 27, 2019, at 2:00PM NICHOLAS HOOPER Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince™ (b. 1957) In Concert There will be one 25-minute intermission. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince™ Synopsis As Lord Voldemort™ tightens his grip on both the Muggle and Wizarding Worlds™, Dumbledore is more intent upon preparing Harry for the battle fast approaching. Even as the showdown looms, romance blossoms for Harry, Ron, and Hermione and their classmates. Love is in the air, but danger lies ahead and Hogwarts may never be the same again. NORMAN HUYNH Norman Huynh has established himself as a conductor with an ability to captivate an audience through a multitude of musical genres. This season, Huynh continues to showcase his versatility in concerts featuring Itzhak Perlman, Hip-Hop artists Nas and Wyclef Jean, and vocal superstar Storm Large. Born in 1988, Huynh is a first generation Asian American and the first in his family to pursue classical music as a career. He is currently the Harold and Arlene Schnitzer Associate Conductor of the Oregon Symphony and maintains an international guest conducting schedule. Upcoming and recent engagements include the Detroit Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Orchestra Sinfònica del Vallès, Eugene Symphony, Grant Park Music Festival, and the Princess Galyani Vadhana Youth Orchestra of Bangkok. He has served as a cover conductor for the New York Philharmonic and Los Angeles Philharmonic with John Williams. Huynh has been at the forefront of moving orchestral music out of the traditional concert hall into venues where an orchestra is not conventionally found.