Pdf 11.13 Mb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G – S C/39/5 ORIGINAL: English/Français/Deutsch/Español DATE/DATUM/FECHA: 2005-10-18

E - F - G – S C/39/5 ORIGINAL: English/français/deutsch/español DATE/DATUM/FECHA: 2005-10-18 INTERNATIONAL UNION UNION INTERNATIONALE INTERNATIONALER UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL FOR THE PROTECTION OF POUR LA PROTECTION VERBAND ZUM SCHUTZ PARA LA PROTECCIÓN NEW VARIETIES DES OBTENTIONS VON PFLANZEN- DE LAS OBTENCIONES OF PLANTS VÉGÉTALES ZÜCHTUNGEN VEGETALES GENEVA GENÈVE GENF GINEBRA COUNCIL CONSEIL DER RAT CONSEJO Thirty-Ninth Ordinary Trente-neuvième session Neununddreißigste ordent- Trigésima novena sesión Session ordinaire liche Tagung ordinaria Geneva, October 27, 2005 Genève, 27 octobre 2005 Genf, 27. Oktober 2005 Ginebra, 27 de octubre de 2005 COOPERATION IN EXAMINATION / COOPÉRATION EN MATIÈRE D’EXAMEN / ZUSAMMENARBEIT BEI DER PRÜFUNG / COOPERACIÓN EN MATERIA DE EXAMEN Document prepared by the Office of the Union / Document établi par le Bureau de l’Union / Vom Verbandsbüro ausgearbeitetes Dokument / Documento preparado por la Oficina de la Unión This document contains a synopsis of offers for cooperation in examination made by authorities, of cooperation already established between authorities and of any envisaged cooperation. * * * * * Le présent document contient une étude synoptique des offres de coopération en matière d’examen faites par les services compétents, de la coopération déjà établie entre des services et de la coopération prévue. * * * * * Dieses Dokument enthält einen Überblick über Angebote für eine Zusammenarbeit bei der Prüfung, die von Behörden abgegeben worden sind, über Fälle einer bereits verwirklichten Zusammenarbeit zwischen Behörden und über Fälle, in denen eine solche Zusammenarbeit beabsichtigt ist. * * * * * Este documento contiene un estudio sinóptico de las ofertas de cooperación en materia de examen realizadas por las autoridades, de la cooperación ya establecida entre autoridades y de cualquier otra cooperación prevista. -

The New Zealand Rain Forest: a Comparison with Tropical Rain Forest! J

The New Zealand Rain Forest: A Comparison with Tropical Rain Forest! J. W. DAWSON2 and B. V. SNEDDON2 ABSTRACT: The structure of and growth forms and habits exhibited by the New Zealand rain forest are described and compared with those of lowland tropical rain forest. Theories relating to the frequent regeneration failure of the forest dominants are outlined. The floristic affinities of the forest type are discussed and it is suggested that two main elements can be recognized-lowland tropical and montane tropical. It is concluded that the New Zealand rain forest is comparable to lowland tropical rain forest in structure and in range of special growth forms and habits. It chiefly differs in its lower stature, fewer species, and smaller leaves. The floristic similarity between the present forest and forest floras of the Tertiary in New Zealand suggest that the former may be a floristically reduced derivative of the latter. PART 1 OF THIS PAPER describes the structure The approximate number of species of seed and growth forms of the New Zealand rain plants in these forests is 240. From north to forest as exemplified by a forest in the far north. south there is an overall decrease in number of In Part 2, theories relating to the regeneration species. At about 38°S a number of species, of the dominant trees in the New Zealand rain mostly trees and shrubs, drop out or become forest generally are reviewed briefly, and their restricted to coastal sites, but it is not until about relevance to the situation in the study forest is 42°S, in the South Island, that many of the con considered. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Plant Charts for Native to the West Booklet

26 Pohutukawa • Oi exposed coastal ecosystem KEY ♥ Nurse plant ■ Main component ✤ rare ✖ toxic to toddlers coastal sites For restoration, in this habitat: ••• plant liberally •• plant generally • plant sparingly Recommended planting sites Back Boggy Escarp- Sharp Steep Valley Broad Gentle Alluvial Dunes Area ment Ridge Slope Bottom Ridge Slope Flat/Tce Medium trees Beilschmiedia tarairi taraire ✤ ■ •• Corynocarpus laevigatus karaka ✖■ •••• Kunzea ericoides kanuka ♥■ •• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Metrosideros excelsa pohutukawa ♥■ ••••• • •• •• Small trees, large shrubs Coprosma lucida shining karamu ♥ ■ •• ••• ••• •• •• Coprosma macrocarpa coastal karamu ♥ ■ •• •• •• •••• Coprosma robusta karamu ♥ ■ •••••• Cordyline australis ti kouka, cabbage tree ♥ ■ • •• •• • •• •••• Dodonaea viscosa akeake ■ •••• Entelea arborescens whau ♥ ■ ••••• Geniostoma rupestre hangehange ♥■ •• • •• •• •• •• •• Leptospermum scoparium manuka ♥■ •• •• • ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Leucopogon fasciculatus mingimingi • •• ••• ••• • •• •• • Macropiper excelsum kawakawa ♥■ •••• •••• ••• Melicope ternata wharangi ■ •••••• Melicytus ramiflorus mahoe • ••• •• • •• ••• Myoporum laetum ngaio ✖ ■ •••••• Olearia furfuracea akepiro • ••• ••• •• •• Pittosporum crassifolium karo ■ •• •••• ••• Pittosporum ellipticum •• •• Pseudopanax lessonii houpara ■ ecosystem one •••••• Rhopalostylis sapida nikau ■ • •• • •• Sophora fulvida west coast kowhai ✖■ •• •• Shrubs and flax-like plants Coprosma crassifolia stiff-stemmed coprosma ♥■ •• ••••• Coprosma repens taupata ♥ ■ •• •••• •• -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Astelia Waialealae

Plants Pa‘iniu Astelia waialealae SPECIES STATUS: Federally Listed as Candidate Medeiros, © Smithsonian 2005 Genetic Safety Net Species IUCN Red List Ranking – Critically Endangered (CR D) Hawai‘i Natural Heritage Ranking‐ Critically Imperiled (G1) Endemism – Kaua‘i SPECIES INFORMATION: Astelia waialealae is a terrestrial rhizomatous perennial herb in the astelia family (Asteliaceae). Plants are short, from a bulbous caudex. Leaves silvery, 12‐20 cm long, and wooly pubescent. Scapes 10‐20 cm long. Racemes 3‐7 cm long. Tepals dark purple and densely pubescent. DISTRIBUTION: Astelia waialealae is endemic to the montane bogs on the central plateau of the island of Kaua‘i. Found only within the Alaka‘i Swamp, Sincock Bog, and Wai‘ale‘ale Summit areas. ABUNDANCE: Three subpopulations are known; with a total population of probably less than ten mature individuals in the Alaka‘i Swamp. The populations have shown a drastic decline over the past ten years. LOCATION AND CONDITION OF KEY HABITAT: Montane bogs located within wet forests in the cloud zone on the central plateau of the island of Kaua‘i. All three of the current occurrences are in Alaka‘i Swamp Wilderness Preserve. THREATS: In the past, most of the bogs have been heavily damaged by feral pigs; Competition with alien plants for light, space, and water; Fire; Small number of remaining individuals. CONSERVATION ACTIONS: The goals of conservation actions are not only to protect current populations, but also to establish further populations to reduce the risk of extinction. In addition to common statewide and island conservation actions, specific actions include: All remaining individuals are within small fenced, weeded, and monitored areas; Augment wild populations and establish new populations in safe harbors; Establish secure ex‐situ stocks with complete representation of remaining individuals. -

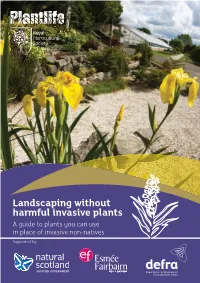

Landscaping Without Harmful Invasive Plants

Landscaping without harmful invasive plants A guide to plants you can use in place of invasive non-natives Supported by: This guide, produced by the wild plant conservation Landscaping charity Plantlife and the Royal Horticultural Society, can help you choose plants that are without less likely to cause problems to the environment harmful should they escape from your planting area. Even the most careful land managers cannot invasive ensure that their plants do not escape and plants establish in nearby habitats (as berries and seeds may be carried away by birds or the wind), so we hope you will fi nd this helpful. A few popular landscaping plants can cause problems for you / your clients and the environment. These are known as invasive non-native plants. Although they comprise a small Under the Wildlife and Countryside minority of the 70,000 or so plant varieties available, the Act, it is an offence to plant, or cause to damage they can do is extensive and may be irreversible. grow in the wild, a number of invasive ©Trevor Renals ©Trevor non-native plants. Government also has powers to ban the sale of invasive Some invasive non-native plants might be plants. At the time of producing this straightforward for you (or your clients) to keep in booklet there were no sales bans, but check if you can tend to the planted area often, but it is worth checking on the websites An unsuspecting sheep fl ounders in a in the wider countryside, where such management river. Invasive Floating Pennywort can below to fi nd the latest legislation is not feasible, these plants can establish and cause cause water to appear as solid ground. -

Astelia Chathamica

Astelia chathamica COMMON NAME Chatham Island astelia or kakaha, Moriori flax SYNONYMS Astelia nervosa var. chathamica Skottsb. FAMILY Asteliaceae AUTHORITY Astelia chathamica (Skottsb.) L.B.Moore FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No Chatham Islands. Photographer: John Sawyer ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Herbs - Monocots NVS CODE ASTCHA CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 70 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | At Risk – Recovering | Qualifiers: CD, IE, RR PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | At Risk – Recovering | Qualifiers: IE, RR 2004 | Threatened – Nationally Endangered BRIEF DESCRIPTION Kakaha has long flax-like leaves clad in silvery hairs. Male and female flowers are found on separate plants. The male flower stalk is very thick Astelia chathamica plant, Chatham (Rekohu) and bears dark green, scented flowers, while the female plant has pale, Island, Rangaika Cliffs, March 1999. greenish-white flowers. Flowering occurs from October to December, Photographer: Geoff Walls while the orange or red fruit may be seen from February to July. DISTRIBUTION Endemic to the Chatham Islands where it is known from Chatham Island and Pitt Island. HABITAT Kakaha occupies a range of moist sites. It can be found on forest floors, cliffs, rock bluffs, lakeshore scarps and stream margins, as well as in swamps. It was formerly widespread, but now tends to be restricted to sheltered, rocky, or protected spots in the bush or scrub where it is safe from grazing. FLOWERING October - December FLOWER COLOURS Green, White FRUITING February - July LIFE CYCLE Fleshy berries are dispersed by frugivory (Thorsen et al., 2009). THREATS Browsing and physical destruction by stock and feral animals have impacted severely on this species. -

Biogeography of the Monocotyledon Astelioid Clade (Asparagales): a History of Long-Distance Dispersal and Diversification with Emerging Habitats

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Biogeography of the monocotyledon astelioid clade (Asparagales): A history of long-distance dispersal and diversification with emerging habitats Birch, Joanne L ; Kocyan, Alexander Abstract: The astelioid families (Asteliaceae, Blandfordiaceae, Boryaceae, Hypoxidaceae, and Lanari- aceae) have centers of diversity in Australasia and temperate Africa, with secondary centers of diversity in Afromontane Africa, Asia, and Pacific Islands. The global distribution of these families makes this an excellent lineage to test if current distribution patterns are the result of vicariance or long-distance dispersal and to evaluate the roles of tertiary climatic and geological drivers in lineage diversification. Sequence data were generated from five chloroplast regions (petL-psbE, rbcL, rps16-trnK, trnL-trnLF, trnS-trnSG) for 104 ingroup species sampled across global diversity. The astelioid phylogeny was inferred using maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian inference methods. Divergence dates were estimated with a relaxed clock applied in BEAST. Ancestral ranges were reconstructed in ’BioGeoBEARS’ applying the corrected Akaike information criterion to test for the best-fit biogeographic model. Diver- sification rates were estimated in Bayesian Analysis of Macroevolutionary Mixtures [BAMM]. Astelioid relationships were inferred as Boryaceae(Blandfordiaceae(Asteliaceae(Hypoxidaceae plus Lanariaceae))). The crown astelioid node was dated to the Late Cretaceous (75.2 million years; 95% highest posterior densities interval 61.0-90.0 million years) with an inferred Eastern Gondwanan origin. However, aste- lioid speciation events have not been shaped by Gondwanan vicariance. Rather long-distance dispersal since the Eocene is inferred to account for current distributions. -

Full Plant Catalogue

Full Plant Catalogue visit us at www.growingspectrum.co.nz or look for us on facebook PMS 323 PMS 254 Contents Mission Statement 1 Company Profile 2 General Information 3 Roses 5 Topiary 7 Perennials & Potted Bulbs 9 Ornamental Shrubs 31 Mission Statement To be a wholesale nursery of honesty and integrity, growing and marketing a wide spectrum of quality plants while providing prompt efficient service to our customers. To have motivated knowledgeable staff, innovative in both production and promotion while caring about the well being and safety of the others we work with and profiting fairly through our efficiency. Growing Spectrum Plant Catalogue • www.growingspectrum.co.nz 1 Company Profile Growing Spectrum is geared to sell 95% to retail Garden Centres, with a lesser volume to landscapers, local bodies and, more recently, overseas companies looking for quality export product. Our Company is focused on producing premium quality plants and has achieved respect throughout the industry for maintaining this focus. Our reputation for experience, quality and being able to predict future trends has gained us recognition as a market leader in the Nursery industry. A large percentage of our product is grown on “spec”; the balance on contract. Growing Spectrum welcomes enquiries from clients requiring contract-grown stock. Our growing area consists of: 20 acres of Field Product and 8 acres of Container Product. We are currently producing over 450,000 plants per annum. Each week our current stock availability is reassessed and updated. A monthly user-friendly catalogue is produced for our extensive client list. In December we also release our Annual Indent Catalogue, enabling customers to forward order product. -

Invasion and Resilience in Lowland Wet Forests of Hawai'i

Vegetation Patterns in Lowland Wet Forests of Hawai'i Presented to the Faculty of the Tropical Conservation Biology and Environmental Science Program University of Hawai`i at Hilo In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Science by Cindy J. Dupuis Hilo, Hawai`i 2012 i © Cindy J. Dupuis 2012 ii iii Stands in Brilliant Composition Here the forest pockets proclaim themselves in plain view Uttering an ancient essence and origin beyond human Stands in brilliant composition The green growth entwined, by branch and by root A fragile glimpse that in itself supersedes strife A niche not nebulous to those embraced Shading the order of diminishing grandeur Far into the moss covered bottoms And this I treasure For so lovely is apportioned the diversity of lives Beyond the appetite of impenetrable invasion These lasting remains in lingering potency Hover, between the likely and the possible C. J. Dupuis iv Acknowledgments: I would like to offer sincere gratitude first and foremost to my advisor, Jonathan Price and to my good friend and committee member, Ann Kobsa. To Jonathan, a wealth of information, an extraordinary mentor, and a committed supporter of this project…thank you! To Ann, the most dedicated individual of Hawaii lowland wet forests imaginable, thank you for your kind generosity and support on all levels of this academic undertaking! Thank you to other committee members, Becky Ostertag and Flint Hughes for your diligent standards, insightful editing, your expertise in, and enthusiasm for Hawaii’s lowland wet forests. Special thanks as well to student peers, co-workers and volunteers who assisted me in very strenuous field work: Ann Kobsa, Tishanna Bailey-Ben, Anya Tagawa, Lincoln Tyler, Eric Akerman. -

Vegetation and the Australian Alps Factsheet

vegetation in THE AUSTRALIAN ALPS Plants provide Aboriginal people with food, fibre, medicine, shelter and tools. Most plants have a song, story, dance and ceremony associated with it. Each plant also has a group of people who have a responsibil- ity to care for and control the use of that plant and the animals linked to it. Only women use some plants while others are associated with men. Plants are used in a similar, if not the same way, wherever they grow across Australia. For example, eucalypts provide weapons and utensils, shelter, firewood, charcoal for art and sap for medicine and tanning skins. Plants that grow at high altitudes are only accessible during summer and this is why there were large gatherings of Aboriginal people in the mountains during the warmer months. The Australian Alps provided a plentiful supply of seeds, berries, nectar and roots to eat and a supply of medicines that were not available at lower altitudes. The bark of some shrubs were used to make string nets to catch Bogong Moths and plants also provided shelter and food for a variety of animals that were also useful to Aboriginal people. The life cycle of some plants indicate the availability of food resources elsewhere and sometimes dictated text: Rod Mason the movement of people. For example, the end of the flowering season of one species may indicate that illustration: Jim Williams it was time for one group of people to leave an area and another to arrive or a certain species of wattle flowering indicates fish are plentiful somewhere else.