December 15, 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boundary Condition Controls on the High-Sand-Flux Regions of Mars Matthew Chojnacki1, Maria E

https://doi.org/10.1130/G45793.1 Manuscript received 8 November 2018 Revised manuscript received 18 January 2019 Manuscript accepted 20 February 2019 © 2019 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 11 March 2019 Boundary condition controls on the high-sand-flux regions of Mars Matthew Chojnacki1, Maria E. Banks2, Lori K. Fenton3, and Anna C. Urso1 1Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA 2National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland 20771, USA 3Carl Sagan Center at the SETI (Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) Institute, Mountain View, California 94043, USA ABSTRACT DATA SETS AND METHODS Wind has been an enduring geologic agent throughout the history of Mars, but it is often To assess bed-form morphology and dynamics, unclear where and why sediment is mobile in the current epoch. We investigated whether we analyzed images acquired by the High Resolu- eolian bed-form (dune and ripple) transport rates are depressed or enhanced in some areas tion Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) cam- by local or regional boundary conditions (e.g., topography, sand supply/availability). Bed- era on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (0.25–0.5 form heights, migration rates, and sand fluxes all span two to three orders of magnitude m/pixel; McEwen et al., 2007; see Table DR1 in across Mars, but we found that areas with the highest sand fluxes are concentrated in three the GSA Data Repository1). Digi tal terrain mod- regions: Syrtis Major, Hellespontus Montes, and the north polar erg. -

Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park and Regional Reserve

<iframe src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/ns.html?id=GTM-5L9VKK" height="0" width="0" style="display:none;visibility:hidden"></iframe> Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park and Regional Reserve About Check the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 30092021.pdf) before visiting this park. Located within the driest region of the Australian continent, the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park is in the centre of the Simpson Desert, one of the world's best examples of parallel dunal desert. The Simpson Desert's sand dunes stretch over hundreds of kilometres and lie across the corners of three states - South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory. The Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Regional Reserve, just outside the Conservation Park, features a wide variety of desert wildlife preserved in a landscape of varied dune systems, extensive playa lakes, spinifex grasslands and acacia woodlands. The reserve links the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park to Witjira National Park. Simpson Desert parks in South Australia and Queensland are closed in summer from 1 December to 15 March. Vehicles are required to have high visibility safety flags (#safety) attached to the front of the vehicle. Opening hours Open daily. Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park and Regional Reserve are closed from 1 December to 15 March each year. Access may be restricted due to local road conditions. Please refer to the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin-30092021.pdf) for current access and road condition information. Closures and safety This park is closed on days of Catastrophic Fire Danger and may also be closed on days of Extreme Fire Danger. -

Australia: State of the Environment 1996: Chapter 4

Chapter 4 . Biodiversity ‘Still Flying’ from the painting of a Wandering Albatross by Richard Prepared by Weatherly. Denis Saunders (Chair), CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology Andrew Beattie, Centre for Biodiversity and Bioresources, School of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University Susannah Eliott (Research Assistant/Science Writer), Centre for Science Communication, University of Technology, Sydney Marilyn Fox, School of Geography, University of New South Wales Burke Hill, CSIRO Division of Fisheries Bob Pressey, New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service Duncan Veal, Centre for Biodiversity and Bioresources, School of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University Jackie Venning, State of Environment Reporting, South Australian Department of Environment and Natural Resources Mathew Maliel (State of the Environment Reporting Unit member), Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories (Facilitator) Charlie Zammit (former State of the Environment Reporting Unit member), Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories (former Facilitator) 4-1 . Australia: State of the Environment 1996 . Contents Introduction. 4-4 Pressure . 4-7 Human populations . 4-9 Urban development . 4-9 Tourism and recreation . 4-9 Harvesting resources and land use. 4-10 Fisheries . 4-10 Forestry . 4-11 Pastoralism. 4-12 Agriculture . 4-12 Introduced species . 4-16 Vertebrates . 4-16 Invertebrates. 4-17 Plants. 4-18 Micro-organisms. 4-20 Native species out of place . 4-20 Pollution . 4-21 Mining . 4-22 Climate change . 4-22 State . 4-23 The state of ecosystem diversity . 4-23 Biogeographic regionalisations for Australia . 4-23 Ecosystem diversity. 4-26 The state of species diversity. 4-30 Number and distribution of species . 4-31 Status of species . -

Conservation Management Zones of Australia

Conservation Management Zones of Australia Mitchell Grasslands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Lawn Hill National Park – Peter Lik Page 4: Kowaris (Dasyuroides byrnei) – Leong Lim Page 10: Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum) – JJ Harrison Page 16: Australian Fossil Mammal Sites (Riversleigh) – World Heritage Listed site – Colin Totterdell Page 18: Mitchell Grasslands -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Summary of Plots in the Lake Eyre Basin

S ummary of Plots in the Lake Eyre Basin 2010 - 2016 Cravens Peak Reserve, QLD Acknowledgments TERN AusPlots Rangelands gratefully acknowledges the staff of the numerous properties both public and private that have helped with the work and allowed access to their land. AusPlots Rangelands also acknowledges the staff from the 4 state and territory governments who have provided assistance on the project. Thanks also to the many volunteers who helped to collect, curate and process the data and samples. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Accessing the Data ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Point intercept data ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Plant collections ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Leaf tissue samples ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Site description information .............................................................................................................................. 3 Structural summary .......................................................................................................................................... -

Energy from the Desert

SUMMARY Energy from the Desert Feasibility of Very Large Scale Photovoltaic Power Generation (VLS-PV) Systems EDITOR Kosuke Kurokawa Energy from the Desert SUMMARY Energy from the Desert Feasibility of Very Large Scale Photovoltaic Power Generation (VLS-PV) Systems EDITOR Kosuke Kurokawa PART THREE: SCENARIO STUDIES AND RECOMMENDATIONS Published by James & James (Science Publishers) Ltd 8–12 Camden High Street, London, NW1 0JH, UK © Photovoltaic Power Systems Executive Committee of the International Energy Agency The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the copyright holder and the publisher. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Printed in Hong Kong by H&Y Printing Ltd Cover image: Horizon Stock Images / Michael Simmons Neither the authors nor the publisher make any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the information contained in this publication, or assume any liability with respect to the use of, or damages resulting from, this information. Please note: in this publication a comma has been used as a decimal point, according to the ISO standard adopted by the International Energy Agency. CHAPTER ELEVEN: CONCLUSIONS OF PART 1 AND PART 2 Contents Foreword vi Preface vii Task VIII Participants viii COMPREHENSIVE SUMMARY Objective 1 Background and concept of VLS-PV 1 VLS-PV case studies 1 Scenario studies 2 Understandings 2 R ecommendations 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. -

Scf Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey

SCF PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY PSWS Technical Report 12 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PILOT PHASE OF THE PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY 2009-2012 November 2012 Dr Tim Wacher & Mr John Newby REPORT TITLE Wacher, T. & Newby, J. 2012. Summary of results and achievements of the Pilot Phase of the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey 2009-2012. SCF PSWS Technical Report 12. Sahara Conservation Fund. ii + 26 pp. + Annexes. AUTHORS Dr Tim Wacher (SCF/Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey & Zoological Society of London) Mr John Newby (Sahara Conservation Fund) COVER PICTURE New-born dorcas gazelle in the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Game Reserve, Chad. Photo credit: Tim Wacher/ZSL. SPONSORS AND PARTNERS Funding and support for the work described in this report was provided by: • His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi • Emirates Center for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) • International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC) • Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF) • Zoological Society of London (ZSL) • Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification (Niger) • Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Halieutiques (Chad) • Direction de la Chasse, Faune et Aires Protégées (Niger) • Direction des Parcs Nationaux, Réserves de Faune et de la Chasse (Chad) • Direction Générale des Forêts (Tunis) • Projet Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes (Niger) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Sahara Conservation Fund sincerely thanks HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, for his interest and generosity in funding the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey through the Emirates Centre for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) and the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC). This project is carried out in association with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). -

By H.D.V. PRENDERGAST a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1

STRUCTURAL, BIOCHEMICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL RELATIONSHIPS IN AUSTRALIAN c4 GRASSES (POACEAE) • by H.D.V. PRENDERGAST A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1987. Canberra, Australia. i STATEMENT This thesis describes my own work which included collaboration with Dr N .. E. Stone (Taxonomy Unit, R .. S .. B.S .. ), whose expertise in enzyme assays enabled me to obtain comparative information on enzyme activities reported in Chapters 3, 5 and 7; and with Mr M.. Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c .. s .. r .. R .. O .. ), whose as yet unpublished taxonomic views on Eragrostis form the basis of some of the discussion in Chapter 3. ii This thesis describes the results of research work carried out in the Taxonomy Unit, Research School of Biological Sciences, The Australian National University during the tenure of an A.N.U. Postgraduate Scholarship. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My time in the Taxonomy Unit has been a happy one: I could not have asked for better supervision for my project or for a more congenial atmosphere in which to work. To Dr. Paul Hattersley, for his help, advice, encouragement and friendship, I owe a lot more than can be said in just a few words: but, Paul, thanks very much! To Mr. Les Watson I owe as much for his own support and guidance, and for many discussions on things often psittacaceous as well as graminaceous! Dr. Nancy Stone was a kind teacher in many days of enzyme assays and Chris Frylink a great help and friend both in and out of the lab •• Further thanks go to Mike Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c.s.I.R.O.) for identifying many grass specimens and for unpublished data on infrageneric groups in Eragrostis; Dr. -

Survey of the Underground Signs of Marsupial Moles in the WA Great Victoria Desert

Survey of the underground signs of marsupial moles in the WA Great Victoria Desert Report to Tropicana Joint Venture and the Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts, Northern Territory Government Joe Benshemesh Martin Schulz September 2008 Marsupial moles in the WA Great Victoria Desert Benshemesh & Schulz 2008 Contents Summary.......................................................................................................................3 Introduction..................................................................................................................5 Methods........................................................................................................................7 Methods........................................................................................................................8 Sites.........................................................................................................................8 Trenches.................................................................................................................9 Moleholes ..............................................................................................................9 Additional data ....................................................................................................9 Results..........................................................................................................................12 Characteristics attributes of backfilled tunnels in WA GVD.............................12 -

(A) Global Distribution of Hyperarid and Dryland Areas Figure 9.2

a Figure 9.2 (a) Global distribution of hyperarid and dryland areas Drylands Dry subhumid areas Dry subhumid areas DrylandsSemiarid areas AridSemiarid areas areas DrylandsDryDry subhumidsubhumid areasareas HyperaridArid areas areas SemiaridSemiaridDryDry subhumidsubhumid areasareas areasareas AridArid areasareasHyperarid areas SemiaridSemiarid areasareas HyperaridHyperarid areasareas Map produced by ZOÏ Environment Network, September 2010 Source: UNEAridAridP W orld areasareas Conservation Monitoring Centre DrylandsHyperaridHyperarid areasareas Map produced by ZOÏ Environment Network, September 2010 MapMap producedproduced byby ZOÏZOÏ EnvironmentEnvironment Network,Network, SeptemberSeptember 20102010 Source: UNEDryP subhumidWorld Conservation areas Monitoring Centre Source:Source:b UNEUNEPP WWorldorld ConservationConservation MonitoringMonitoring CentreCentre DrylandsSemiarid areas Arid areas Figure 9.2 DryDry subhumidsubhumid areasareas Hyperarid areas SemiaridSemiarid areasareas (b) Regions MapMap producedproduced byby ZOÏZOÏ EnvironmentEnvironment Network,Network, SeptemberSeptember 20102010 Source:Source: UNEUNEPPAridArid WW areasorldareasorld ConservationConservation MonitoringMonitoring CentreCentre vulnerable to HyperaridHyperarid areasareas Map produced by ZOÏ Environment Network, September 2010 Source: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre desertification MapMap producedproduced byby ZOÏZOÏ EnvironmentEnvironment Network,Network, SeptemberSeptember 20102010 Source:Source: UNEUNEPP WWorldorld ConservationConservation MonitoringMonitoring -

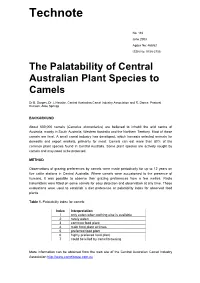

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2.