The Importance of Time Zone Assignment: Evidence from Residential Electricity Consumption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hourglass User and Installation Guide About This Manual

HourGlass Usage and Installation Guide Version7Release1 GC27-4557-00 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, be sure to read the general information under “Notices” on page 103. First Edition (December 2013) This edition applies to Version 7 Release 1 Mod 0 of IBM® HourGlass (program number 5655-U59) and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. Order publications through your IBM representative or the IBM branch office serving your locality. Publications are not stocked at the address given below. IBM welcomes your comments. For information on how to send comments, see “How to send your comments to IBM” on page vii. © Copyright IBM Corporation 1992, 2013. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this manual ..........v Using the CICS Audit Trail Facility ......34 Organization ..............v Using HourGlass with IMS message regions . 34 Summary of amendments for Version 7.1 .....v HourGlass IOPCB Support ........34 Running the HourGlass IMS IVP ......35 How to send your comments to IBM . vii Using HourGlass with DB2 applications .....36 Using HourGlass with the STCK instruction . 36 If you have a technical problem .......vii Method 1 (re-assemble) .........37 Method 2 (patch load module) .......37 Chapter 1. Introduction ........1 Using the HourGlass Audit Trail Facility ....37 Setting the date and time values ........3 Understanding HourGlass precedence rules . 38 Introducing -

Atomic Desktop Alarm Clock

MODEL: T-045 (FRONT) INSTRUCTION MANUAL SCALE: 480W x 174H mm DATE: June 3, 2009 COLOR: WHITE BACKGROUND PRINTING BLACK 2. When the correct hour appears press the MODE button once to start the Minute digits Activating The Alarm Limited 90-Day Warranty Information Model T045 flashing, then press either the UP () or DOWN () buttons to set the display to the To turn the alarm ‘On’ slide the ALARM switch on the back panel to the ‘On’ position. The correct minute. Alarm On indicator appears in the display. Timex Audio Products, a division of SDI Technologies Inc. (hereafter referred to as SDI Technologies), warrants this product to be free from defects in workmanship and materials, under normal use Atomic Desktop 3. When the correct minutes appear press the MODE button once to start the Seconds At the selected wake-up time the alarm turns on automatically. The alarm begins with a single and conditions, for a period of 90 days from the date of original purchase. digits flashing. If you want to set the seconds counter to “00” press either the UP () or ‘beep’ and then the frequency of the ‘beeps’ increases. The alarm continues for two minutes, Alarm Clock DOWN () button once. If you do not wish to ‘zero’ the seconds, proceed to step 4. then shuts off automatically and resets itself for the same time on the following day. Should service be required by reason of any defect or malfunction during the warranty period, SDI Technologies will repair or, at its discretion, replace this product without charge (except for a 4. -

Daylight Saving Time (DST)

Daylight Saving Time (DST) Updated September 30, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45208 Daylight Saving Time (DST) Summary Daylight Saving Time (DST) is a period of the year between spring and fall when clocks in most parts of the United States are set one hour ahead of standard time. DST begins on the second Sunday in March and ends on the first Sunday in November. The beginning and ending dates are set in statute. Congressional interest in the potential benefits and costs of DST has resulted in changes to DST observance since it was first adopted in the United States in 1918. The United States established standard time zones and DST through the Calder Act, also known as the Standard Time Act of 1918. The issue of consistency in time observance was further clarified by the Uniform Time Act of 1966. These laws as amended allow a state to exempt itself—or parts of the state that lie within a different time zone—from DST observance. These laws as amended also authorize the Department of Transportation (DOT) to regulate standard time zone boundaries and DST. The time period for DST was changed most recently in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT 2005; P.L. 109-58). Congress has required several agencies to study the effects of changes in DST observance. In 1974, DOT reported that the potential benefits to energy conservation, traffic safety, and reductions in violent crime were minimal. In 2008, the Department of Energy assessed the effects to national energy consumption of extending DST as changed in EPACT 2005 and found a reduction in total primary energy consumption of 0.02%. -

How to Add Another Time Zone to a Lotus Notes Calendar

How to Add Another Time Zone to a Lotus Notes Calendar Adding another Lotus Notes 8 allows users to set up more than one time zone in their calendar views. time zone to Please follow the steps in the table below to add another time zone to your calendar. Lotus Notes Calendar Note: This process has only been tested for Lotus Notes 8. Step Action 1 Open Lotus Notes 2 Navigate to the Calendar 3 In the lower right corner, click on the In Office drop-down menu and select Edit Locations… 4 In the navigator on the left, select Calendar and To Do, then Regional Settings 5 In the Time Zone section, checkmark the Display an additional time zone option 6 Enter the Time zone label that you wish to use Note: This is a free-form text field and is for the user only. It does not impact any system functionality. 7 Use the Time Zone drop-down to select the time zone that you wish to add Continued on next page How To Add Another Time Zone To A Lotus Notes Calendar.Doc Page 1 of 2 How to Add Another Time Zone to a Lotus Notes Calendar, Continued Adding another time zone to Step Action Lotus Notes 8 As desired, checkmark the Display an additional time zone in the main calendar Calendar and/or the Display an additional time zone in the Day-At-A-Glance calendar options (continued) 9 Once all options have been filled out, click the Save button 10 Verify that the calendar displays the time zones correctly How To Add Another Time Zone To A Lotus Notes Calendar.Doc Page 2 of 2 . -

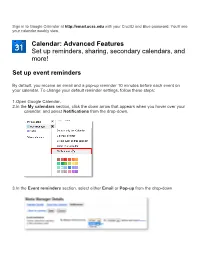

Calendar: Advanced Features Set up Reminders, Sharing, Secondary Calendars, and More!

Sign in to Google Calendar at http://email.ucsc.edu with your CruzID and Blue password. You'll see your calendar weekly view. Calendar: Advanced Features Set up reminders, sharing, secondary calendars, and more! Set up event reminders By default, you receive an email and a pop-up reminder 10 minutes before each event on your calendar. To change your default reminder settings, follow these steps: 1. Open Google Calendar. 2. In the My calendars section, click the down arrow that appears when you hover over your calendar, and select Notifications from the drop-down. 3. In the Event reminders section, select either Email or Pop-up from the drop-down. 4. Enter the corresponding reminder time (between one minute and four weeks). 5. Optionally, click Add a reminder to create a new reminder or remove to delete an existing reminder. 6. Click Save. Set up event notifications By default, you receive an email message when someone invites you to a new event, changes or cancels an existing event, or responds to an event. To change your default notification settings, follow these steps: 1. Open Google Calendar. 2. In the My calendars section, click the down arrow that appears when you hover over your calendar, and select Notifications from the drop-down. 3. In the Choose how you would like to be notified section, select the Email check box for each type of notification you’d like to receive. 4. Click Save. Note: If you select the Daily agenda option, the emailed agenda won’t reflect any event changes made after 5am in your local time zone. -

Cozi Calendar Helps Your Family Coordinate Daily Activities: See Who's Doing What Each Day, Who Is Supposed to Pick up Whom from School, and So On

Web sign in Family calendar Getting started with the shared family calendar Entering appointments Coordinating schedules between family members Color coding Describing things you do every week (or month, etc.) Understanding why some appointments appear bold Getting reminders for appointments Printing Getting Started Setting your home time zone Family Calendar Related features: Activity schedules Internet calendars (including holiday and school calendars) Contacts Family calendar gadget Shopping Lists Getting started with the shared family calendar To Do Lists The Cozi Calendar helps your family coordinate daily activities: see who's doing what each day, who is supposed to pick up whom from school, and so on. Messages From your Cozi home page, clicking anywhere on the calendar preview displays the Cozi Calendar. Family Journal Entering appointments Cozi Collage If you’re entering a whole bunch of related appointments for a school, sports, club, or childcare schedule, you can quickly enter them as an activity schedule. Mobile Access You can add an appointment to the family calendar by doing one of the following: Cozi Express Type an appointment directly in the text box at the top of the calendar. You can quickly enter an appointment using your own words. Type the appointment the way you would describe it in everyday language; for example, "Lunch, 12:00 tomorrow". Cozi identifies the date and time of the appointment and puts it in the right place in the family calendar. If you don't specify a name, the appointment applies to All, and will -

SUNDIALS \0> E O> Contents Page

REG: HER DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Letter 1 1-3 BUREAU OF STANDARDS Circular WASHINGTON LC 3^7 (October Jl., 1932) Prepared by R. E. Gould, Chief, Time Section ^ . fA SUNDIALS \0> e o> Contents Page I. Introduction „ 2 II. Corrections to be applied 2 1. Equation of time 3 III. Construction 4 1. Materials and foundation 4 2. Graphical construction for a horizontal sundial 4 3. Gnomon . 5 4. Mathematical construction ........ 6 5,. Illustrations Fig. 1. Layout of a dial 7 Fig. 2. Suggested forms g IV. Setting up the dial 9 V. Mottoes q VI. Bibliography -10 . , 2 I. Introduction One of the earliest methods of determining time was by observing the position of the shadow cast by an object placed in the sunshine. As the day advances the shadow changes and its position at any instant gives an indication of the time. The relative length of the shadow at midday can also be used to indicate the season of the year. It is thought that one of the purposes of the great pyramids of Egypt was to indicate the time of day and the progress of the seasons. Although the origin of the sundial is very obscure, it is known to have been used in very early times in ancient Babylonia. One of the earliest recorded is the Dial of Ahaz 0th Century, B. C. mentioned in the Bible, II Kings XX: 0-11. , The Greeks used sundials in the 4th Century B. C. and one was set up in Rome in 233 B. C. Today sundials are used largely for decorative purposes in gardens or on lawns, and many inquiries have reached the Bureau of Standards regarding the construction and erection of such dials. -

Latitudinal Trends in Human Primary Activities

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Latitudinal trends in human primary activities: characterizing the winter day as a synchronizer Received: 29 August 2017 José María Martín-Olalla Accepted: 15 March 2018 This work analyzes time use surveys from 19 countries (17 European and 2 American) in the middle Published: xx xx xxxx latitude (38–61 degree) accounting for 45% of world population in this range. Time marks for primary activities are contrasted against light/dark conditions. The analysis reveals winter sunrise synchronizes labor start time below 54 degree, occurring within winter civil twilight. Winter sunset is a source of synchronization for labor end times. Winter terminator punctuate meal times in Europe: dinner occurs 3 h after winter sunset time within 1 h; 40% narrower than variability of dinner local times. The sleep- wake cycle of laborers is shown to be related to winter sunrise whereas standard population’s appears to be irrespective of latitude. The signifcance of the winter terminator depends on two competing factors average labor time (~7 h30 m) and the shortest photoperiod. Winter terminator gains signifcance when both roughly matches. That is within a latitude range from 38 degree to 54 degree. The signifcance of winter terminator as a source of synchronization is also related to contemporary year round time schedules: the shortest photoperiod represents the worst case scenario the society faces. Earth’s rotation period (one day or T = 24 h, the defnition of hour) notably infuences biological rhythms1,2 and social human behavior. It is also the time basis to which mechanical clocks are sync. Clocks track time ofset rela- tive to the subsolar meridian— the great circle intersecting Earth’s rotation axis and the subsolar point, where the Sun is directly overhead— hence clock time is insensitive to latitude. -

Special Commission on Commonwealth's Time Zone Report

Report of the Special Commission on the Commonwealth’s Time Zone November 1, 2017 1 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................3 Purpose of the Commission .......................................................................................6 Structure of the Commission .....................................................................................6 Background ................................................................................................................8 Findings ....................................................................................................................12 Economic Development: Commerce and Trade ...................................................12 Labor and Workforce ............................................................................................14 Public Health .........................................................................................................15 Energy ...................................................................................................................16 Crime and Criminal Justice...................................................................................18 Transportation .......................................................................................................19 Broadcasting .........................................................................................................20 Education and School Start-Times .......................................................................21 -

Native American Students' Understandings of Geologic Time Scale

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 46 ( 2012 ) 3159 – 3163 WCES 2012 Native American students’ understandings of geologic time scale: th 4-8 grade students’ understandings of earth’s geologic history Engin Karahan a *, Younkyeong Nam b, Gillian Roehrig c, Tamara Moored aGraduate Research Assistant, University of Minnesota, 320 Learning&Environmental Sciences 1954 Buford Ave, St Paul 55108, USA bPost-doctoral Associate, University of Minnesota, 320 Learning&Environmental Sciences 1954 Buford Ave, St Paul 55108, USA cAssociate Professor, University of Minnesota, 320 Learning&Environmental Sciences 1954 Buford Ave, St Paul 55108, USA dAssistant Professor, University of Minnesota, 320 Learning&Environmental Sciences 1954 Buford Ave, St Paul 55108, USA Abstract Geologic time scales is very important concept for understanding earth system events such as global climate change. However, understanding of geologic time scale in a relationship with human history is very difficult because of relatively short period of human existence in earth history. This study shows that Native American elementary students understand geological and historical event based on relative order of earth history. They understand Earth’s geological event as a sequential series. More importantly, they understand human history based on their own culture and history. © 20122012 Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier Ltd. Ltd. Selection and/or peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Uzunboylu Keywords: Geologic time scale, absolute time, relative time; 1. Introduction Under the increasing pressure of public concerns about environmental issues such as global warming and destruction of ecosystems, understandings of earth as a system have become essential for a scientifically literate citizenry. -

Atomix Atomic Clock 00562 Instructions

Atomix Atomic Clock Model 00562 About the Atomic Clock The National Institute of Standard and Technology (NIST) in Fort Collins, Colorado broadcasts the time signal (WWVB at 60 kHz AM radio signal) with an accuracy of 1 second per every 3,000 years. The signal is able to cover a distance of up to 2,000 miles from the source. Like a typical AM radio, your atomic clock will not be able to receive the WWVB signal in places surrounded by heavy concrete or metal panels. The reception of the time signal is also greatly affected by electrical or electronic interference. To get the best performance from the atomic clock, install the clock nearer to a window facing west. Battery Installation and Set Up Remove the battery cover and insert 2 “AA” alkaline batteries according to the direction shown inside the battery compartment. Once the batteries are installed the display will show all segments of the LCD display for 3 seconds and will beep once. Then the display will show 12:00pm Jan 1, 2000 together with room temperature. The Time Zone is defaulted at PST – Pacific Standard Time. Select the correct Timer Zone 1. Press the ZONE / DST button to select PST, MST, CST or EST. 2. Once a time zone is selected, your Atomix clock will start searching for the time signal. 3. While your Atomix clock is seeking the signal, the signal strength icon will change gradually indicating the search is continuing. 4. If the signal is available, your Atomix clock will display the local time in about 3-5 minutes. -

Any Time Zone to Any Time Zone: a Macro to Convert Anything Joe Deshon

Paper 4742-2020 Any Time Zone to Any Time Zone: A Macro to Convert Anything Joe DeShon ABSTRACT This paper describes a flexible and fully configurable macro that converts a datetime stamp from any time zone to any other time zone. The macro can be configured to operate with any and all of the more than 24 time zones in the world. INTRODUCTION Our company is a large multi-national manufacturing business with operations in almost every time zone in the world. In addition, we often need to query databases that are maintained in Germany, England, Belgium, Spain, Argentina, Columbia, Brazil, Connecticut, Kansas City, Mexico, Philippines, Singapore, Korea, and China. Many of these databases write records with datetime stamps in their local time. SAS time zone conversion functions generally convert only local time zones. We needed an all-purpose macro capable of converting a datetime stamp from any time zone to any time zone with the need for the user to know what the conversion factors are. This paper will demonstrate our solution to the problem: A simple, flexible, and customizable macro that will allow the conversion of a datetime from any time zone to any time zone. EXAMPLE PROBLEMS What is the time in Kansas City (Daylight Time) when the time is noon in Germany (Summer Time)? What is the time in China when the time is 1:00 AM in Buenos Aires? SAS TIME ZONE FUNCTIONS Base SAS™ provides several functions to convert one time zones, but they are concerned with converting the local time to GMT or the other way around.