Damage, Losses and Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civilian Impact Monitoring Report

Civilian Impact Monitoring Report February 2018 Mountain Town, Yemen by Rod Waddington A bi-monthly report on civilian impact from armed violence in Al-Hudaydah, Sa’ada, Sana’a, Capital and Marib. December 2017 - January 2018. Table of content Executive Summary 3 Introduction 6 Methodology 6 Section 1: Overall Data trends 7 Section 4: Capital 32 1.1. Conflict developments December & January 7 4.1. Conflict developments December & January 32 1.2. Civilian impact 8 4.2. Civilian impact & protection implication 33 1.3. Direct protection implication 10 4.3. Geographical spread 35 1.4. Indirect protection implication 11 4.4. Type of armed violence and casualties over time 37 1.5. Geographical spread of incidents 12 1.6. Type of armed violence 14 Section 5: Sana’a 38 1.7. Type of impact per governorate 15 5.1. Conflict developments December & January 38 1.8. Civilian casualties 16 5.2. Civilian impact & protection implication 39 1.9. Casualties per type of armed violence 18 5.3. Geographical spread 41 5.4. Type of armed violence and casualties over time 43 Section 2: Al-Hudaydah 19 2.1 Conflict developments December & January 19 Section 6: Marib 44 2.2 Civilian impact & protection implication 20 6.1. Conflict developments December & January 44 2.3 Geographical spread 22 6.2. Civilian impact & protection implication 45 2.4 Type of armed violence and casualties over time 24 6.3. Geographical spread 47 6.4. Type of armed violence and casualties over time 49 Section 3: Sa’ada 25 3.1. Conflict developments December & January 25 3.2. -

Tentative Lists Submitted by States Parties As of 15 April 2021, in Conformity with the Operational Guidelines

World Heritage 44 COM WHC/21/44.COM/8A Paris, 4 June 2021 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Extended forty-fourth session Fuzhou (China) / Online meeting 16 – 31 July 2021 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8A. Tentative Lists submitted by States Parties as of 15 April 2021, in conformity with the Operational Guidelines SUMMARY This document presents the Tentative Lists of all States Parties submitted in conformity with the Operational Guidelines as of 15 April 2021. • Annex 1 presents a full list of States Parties indicating the date of the most recent Tentative List submission. • Annex 2 presents new Tentative Lists (or additions to Tentative Lists) submitted by States Parties since 16 April 2019. • Annex 3 presents a list of all sites included in the Tentative Lists of the States Parties to the Convention, in alphabetical order. Draft Decision: 44 COM 8A, see point II I. EXAMINATION OF TENTATIVE LISTS 1. The World Heritage Convention provides that each State Party to the Convention shall submit to the World Heritage Committee an inventory of the cultural and natural sites situated within its territory, which it considers suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List, and which it intends to nominate during the following five to ten years. Over the years, the Committee has repeatedly confirmed the importance of these Lists, also known as Tentative Lists, for planning purposes, comparative analyses of nominations and for facilitating the undertaking of global and thematic studies. -

Republic of Yemen Air Transport Sector Review Note

Republic of Yemen Air Transport Sector Review Note May, 2009 Middle East and North Africa Region Energy and Transport Unit CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange rate effective on January, 2009) Currency Unit = Yemeni Rial (YER) 1 YER = 0.005 USD 1 USD = 200 YER Fiscal Year: January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACAC Arab Civil Aviation Commission ADE Aden International Airport AOC Air Operator Certificate ATC Air Traffic Control ATIS Automated Terminal Information System BASA Bilateral Air Service Agreements CAMA Civil Aviation and Meteorological Authority of Yemen FIR Fligths Information Region GNSS Global Navigation Satellite Systems GoY Government of Yemen GPS Global Positioning System IATA International Air Transport Association ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization ILS Instrument Landing Approach MoT Ministry of Transport RIY Al-Mukalla Airport SAH Sana’a International Airport SARP Standards and Recommended Practices UAE United Arab Emirates USOAP Universal Safety Oversight Audit Programme VOR - DME VHF Omni-Directional Radio Range - Distance Measuring Equipment 2/65 January 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 4 I. THE AIR TRANSPORT SECTOR AT A GLANCE ....................................................................... 9 II. AIR TRANSPORT SERVICES AND COMPETITION POLICY..........................................10 A. DOMESTIC AIR TRANSPORT ...............................................................................................................10 -

Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study: Market Functionality and Community Perception of Cash Based Assistance

INTER-AGENCY JOINT CASH STUDY: MARKET FUNCTIONALITY AND COMMUNITY PERCEPTION OF CASH BASED ASSISTANCE YEMEN REPORT DECEMBER 2017 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 Cash and Market Working Group Partners The following organisations contributed to the production of this report, as members of the Cash and Market Working Group for Yemen (CMWG) 1 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 Cover Image: OCHA/ Charlotte Cans, Sana’a, June 2015. https://ocha.smugmug.com/Countries/Yemen/General-views-Sanaa/i-CrmGpCB About REACH REACH facilitates the development of information tools and products that enhance the capacity of aid actors to make evidence-based decisions in emergency, recovery and development contexts. All REACH activities are conducted through inter-agency aid coordination mechanisms. For more information, you can write to our in-country office: [email protected]. You can view all our reports, maps and factsheets on our resource centre: reachresourcecentre.info, visit our website at reach-initiative.org, and follow us @REACH_info 2 Inter-Agency Joint Cash Study - 2017 SUMMARY Since 2015, conflict in Yemen has left 3 million people displaced and over half of the population food insecure, and has destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure1. As of July 2017, much of the population had lost their primary source of income, 46% lacked access to a free improved water source2, and an outbreak of cholera had become the largest in modern history.3 The Cash and Market Working Group (CMWG) estimated that in 2016, cash transfer programmes were conducted in 22 governorates across Yemen; however, it found little evidence to determine which method of financial assistance is the most suitable in the context of Yemen. -

Cyclone Luban

Yemen: Cyclone Luban Flash Update 2 | 17 October 2018 Situation Overview Thousands of people have been displaced by Tropical Cyclone “Luban” that made landfall on the coast of Yemen on 14 October. Three people are confirmed dead, 14 missing and more than 100 injured according to the Al Maharah Emergency Operations Room. The cyclone lost strength and has been downgraded to a Tropical Depression as of 15 October. In the last three days, several districts have been flooded following heavy rains, causing a significant number of houses to collapse. Al Maharah is the most seriously affected governorate with heavy to medium rains still falling in northern areas of Man’ar, Sayhut, Al Masilah and Qishn districts. Continuing rains might trigger further flooding towards coastal areas of Al Ghaydah, Hat, Shahn, and Hawf districts. In Al Masilah District, the main bridge that connects Al Maharah and Hadramaut governorates has been seriously damaged with humanitarian partners trying to find alternative access roads from Al Mukalla. The road that links The road that links Hawf District to Oman has been damaged. Photo: Al Maharah Hawf District to Oman is also seriously Emergency Operations Room damaged. The flood damage is preventing access to affected populations in the coastal districts of Al Masilah, Sayhut, Qishn, Huswain, Al Ghaydah and Hawf. Access is partially possible to Sayhut and Al Masilah districts. The electricity supply in the provincial capital of Al Ghaydah and other coastal districts such as Qishn, has been disrupted. Telephone communication with some areas, particularly Hawf District, is cut off. Helicopters have been used to evacuate 350 people so far from areas surrounded by floods. -

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

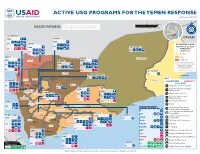

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S. -

Struggle for Citizenship.Indd

From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen CRU Report From the struggle for citizenship to the fragmentation of justice FROM THE STRUGGLE FOR CITIZENSHIP TO THE FRAGMENTATION OF JUSTICE Yemen from 1990 to 2013 Erwin van Veen Conflict Research Unit, The Clingendael Institute February 2014 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Clingendael Institute P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/ Table of Contents Executive summary 7 Acknowledgements 11 Abbreviations 13 1 Introduction 14 2 Selective centralisation of the state: Commerce and security through networked rule 16 Enablers: Tribes, remittances, oil and civil war 17 Tools: Violence, business and religion 21 The year 2011 and the National Dialogue Conference 26 The state of justice in 1990 and 2013 28 3 Trend 1: The ‘instrumentalisation’ of state-based justice 31 Key strategies in the instrumentalisation of justice 33 Consequences of politicisation and instrumentalisation 34 4 Trend 2: The weakening of tribal customary law 38 Functions and characteristics of tribal law 40 Key factors that have weakened tribal law 42 Consequences of weakened tribal law 44 Points of connection -

Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis Economic Warfare & The

HUMANITARIAN AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis Economic Warfare & the Humanitarian Context January 2017 HUMANITARIAN FORESIGHT THINK TANK HUMANITARIAN FORESIGHT THINK TANK Yemen Six Month Economic Analysis / January 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An inclusive political solution to the conflict is unlikely in the next six months, despite the high possibility of state economic collapse and a metastasizing humanitarian crisis across the country. President Hadi’s refusal to accept the terms of a recent UN peace plan is likely stalling Saudi financial relief and threatens to fracture his support base in the south. Meanwhile, the crippled state economy is supporting a thriving shadow economy, which will fragment power structures on both sides of the conflict as stakeholders engage in war profiteering. Not only will this diminish the chances for unity in the long run, it also increases food insecurity and poverty for the most vulnerable, while benefiting those in power who already dominate the parallel market. Amidst this turmoil, AQAP and IS influence will increase. This report will examine the economic context affecting humanitarian needs in Yemen, and present scenarios offering potential trajectories of the conflict to assist in humanitarian preparedness. Source: Ali Zifan (6 December 2016), Insurgency in Yemen detailed map, Wikipedia INTRODUCTION The slow progress in the war between the internationally-recognized Yemeni government of Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and the Zaidi Shia Houthi-Ali Abdallah Saleh alliance has caused the Saudi- backed Hadi coalition to instrumentalise the Yemeni economy, conducting a war of attrition. As Sanaa’s Central Bank of Yemen (CBY) hemorrhaged through its reserves in the previous two years of war, growing criticism of the governor’s alleged complicity in Houthi embezzlement culminated in the 18 September decision by the Hadi government to move the CBY from the Houthi-controlled capital to Aden and position a new governor to run the institution. -

Republic of Yemen NATIONAL REPORT

Republic of Yemen Republic of Yemen NATIONAL REPORT Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development - HABITAT III - 2016, Quito/ Ecuador Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges ......................................................................................... 7 1. Managing rapid urbanization .......................................................................................................... 7 2. Managing rural‐urban linkages ....................................................................................................... 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs ....................................................................................................... 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged ........................................................................................... 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development ................................................................................... -

Yemen Humanitarian Situation Report May 2019

UNICEF YEMEN HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT MAY 2019 - Yemen Humanitarian Situation Report marginalized community during a cholera prevention session conducted femaleby religious leaders in in Al Hasabah district, Sana’a.in ©UNICEF Yemen/2019/Mona Adel. childA from a Highlights May 2019 • On 16 May, multiple air strikes hit various locations in Amanat Al Asimah and Sana’a 12.3 million governorates, killing children and wounding more than 70 civilians. Seven children # of children in need of humanitarian between the ages of 4 and 14 were also killed on 24 May in an attack on the Mawiyah assistance (estimated) district, in the southern Yemeni city of Taiz. This attack increased the verified number 24.1 million # of people in need of children killed and injured the escalation of violence near Sanaa and in Taiz to 27 in (OCHA, 2019 Yemen Humanitarian Needs only 10 days, but the actual numbers are likely to be much higher. Overview) • The number of Acute Watery Diarrhoea/suspected cholera cases has continued to rise 1.71 million since the start of 2019, with 312 out of 333 districts reporting suspected cases this year # of children internally displaced (IDPs) so far. Since 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2019, there have been 365,223 suspected cases 4.7 million and 638 associated deaths recorded (CFR 0.20 per cent). Children under five represent # of children in need of educational assistance 360,000 a quarter of the total suspected cases. # of children under 5 suffering Severe Acute • UNICEF continues to assess and monitor the nutrition situation in Yemen. -

Yemen Country Office

Yemen Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Yemen/2020 Reporting Period: 1 – 31 March 2021 © UNICEF/2021/Yemen Situation in Numbers (OCHA, 2021 Humanitarian Needs Overview) Highlights 11.3 million • The humanitarian situation in Ma’rib continued to be of concern, and with various children in need of waves of violence during the reporting period, the situation showed no signs of humanitarian assistance improvement. People’s lives remained to be impacted every day by fighting, and thousands were being displaced from their homes and displacement sites. Conflict continued as well as in Al Hodeidah, Taizz, and Al Jawf. 20.7 million • In March, 30,317 IDPs were displaced, with the majority of displacement waves people in need coming from Ma’rib, Al Hodeidah, Taizz and Al-Jawf, as internal displacement within governorates towards safer districts increased. • The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) reached an additional 3,500 newly displaced 1.58 million families, 2,200 families of which were in Ma’rib (24,500 individuals). Beneficiaries children internally displaced received RRM kits that included food, family basic hygiene kits, and female dignity kits. (IDPs) • As of 5 April 2021, there were 4,798 COVID-19 officially confirmed cases in Yemen, with 946 associated deaths and 1,738 recovered cases (resulting in a 19.7 per cent confirmed fatality rate). 382 suspected cases were health workers, or 4.78 per cent of the total cases. Funding Status UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status 2021 Appeal: $576.9M SAM Admission 15% n Funding status -

How the Germans Brought Their Communism to Yemen

Miriam M. Müller A Spectre is Haunting Arabia Political Science | Volume 26 This book is dedicated to my parents and grandparents. I wouldn’t be who I am without you. Miriam M. Müller (Joint PhD) received her doctorate jointly from the Free Uni- versity of Berlin, Germany, and the University of Victoria, Canada, in Political Science and International Relations. Specialized in the politics of the Middle East, she focuses on religious and political ideologies, international security, international development and foreign policy. Her current research is occupied with the role of religion, violence and identity in the manifestations of the »Isla- mic State«. Miriam M. Müller A Spectre is Haunting Arabia How the Germans Brought Their Communism to Yemen My thanks go to my supervisors Prof. Dr. Klaus Schroeder, Prof. Dr. Oliver Schmidtke, Prof. Dr. Uwe Puschner, and Prof. Dr. Peter Massing, as well as to my colleagues and friends at the Forschungsverbund SED-Staat, the Center for Global Studies at the University of Victoria, and the Political Science Depart- ment there. This dissertation project has been generously supported by the German Natio- nal Academic Foundation and the Center for Global Studies, Victoria, Canada. A Dissertation Submitted in (Partial) Fulfillment of the Requirements for the- Joint Doctoral Degree (Cotutelle) in the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences ofthe Free University of Berlin, Germany and the Department of Political Scien- ceof the University of Victoria, Canada in October 2014. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non- commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author.