PALS Review 2015 Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE and SAMPLE History Approach Basic Emergency Care Course Objectives • List the hazards that must be considered when approaching an ill or injured person • List the elements to approaching an ill or injured person safely • List the components of the systematic ABCDE approach to emergency patients • Assess an airway • Explain when to use airway devices • Explain when advanced airway management is needed • Assess breathing • Explain when to assist breathing • Assess fluid status (circulation) • Provide appropriate fluid resuscitation • Describe the critical ABCDE actions • List the elements of a SAMPLE history • Perform a relevant SAMPLE history. Essential skills • Assessing ABCDE • Needle-decompression for tension • Cervical spine immobilization pneumothorax • • Full spine immobilization Three-sided dressing for chest wound • • Head-tilt and chin-life/jaw thrust Intravenous (IV) line placement • • Airway suctioning IV fluid resuscitation • • Management of choking Direct pressure/ deep wound packing for haemorrhage control • Recovery position • Tourniquet for haemorrhage control • Nasopharyngeal (NPA) and oropharyngeal • airway (OPA) placement Pelvic binding • • Bag-valve-mask ventilation Wound management • • Skin pinch test Fracture immobilization • • AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) Snake bite management assessment • Glucose administration Why the ABCDE approach? • Approach every patient in a systematic way • Recognize life-threatening conditions early • DO most critical interventions first - fix problems before moving on -

Strategies to Support the COVID-19 Response in Lmics a Virtual Seminar Series Screening, Triage and Patient Flow

Strategies to support the COVID-19 response in LMICs A virtual seminar series Screening, Triage and Patient Flow Bhakti Hansoti, MBChB, MPH, PhD - Associate Professor in Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University OBJECTIVES 1. Clinical Features 2. Preparing the Department 3. Initial Management 4. Other Management Considerations 5. Summary Clinical Features Severity • Most people with COVID-19 develop mild or uncomplicated illness • Approximately 14% develop severe disease requiring hospitalization and oxygen support • 5% require admission to an intensive care unit • In severe cases, COVID-19 can be complicated by • Acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS) • Sepsis and septic shock • Multiorgan failure, including acute kidney injury and cardiac injury. Preparing the Department Elements to be assessed have been divided into the following areas: • Establishment of a core team and key internal and external contact points • Human, material and facility capacity • Communication and data protection • Hand hygiene, personal protective equipment (PPE), and waste management • Triage, first contact and prioritization • Patient placement, moving of the patients in the facility, and visitor access • Environmental cleaning https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/checklist- hospitals-preparing-reception-and-care-coronavirus-2019-covid-19 Split flow Protecting Yourself These videos can help with PPE donning and doffing technique: • Donning and doffing PPE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I94l IH8xXg8 • Recommended PPE during care https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPL -

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols Protocols Table of Contents GENERAL PROVISIONS ................................................................................................ 3 DESTINATION DECISION SUMMARY-METRO BAKERSFIELD AREA ........................ 5 DETERMINATION OF DEATH ..................................................................................... 12 101 AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION ...................................................................................... 16 102 ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS ............................................................ 18 103 ALLERGIC REACTION/ANAPHYLAXIS ................................................................ 20 104 ASYSTOLE/ PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY ............................................. 22 105 BITES STINGS ENVENOMATION ......................................................................... 24 106 BRADYCARDIA ..................................................................................................... 26 107 BRIEF RESOLVED UNEXPLAINED EVENT ......................................................... 29 108 BURNS ................................................................................................................... 32 109 CHEMPACK ........................................................................................................... 35 110 CHEST PAIN OR ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME ........................................... 37 111 CHEST TRAUMA .................................................................................................. -

High Performance CPR Update

High Performance CPR Update Page | 1 Final Revision 8/8/2012 As part of our ongoing Quality Assurance in Cardiac Arrest incidents, Skagit County EMS under the direction of Dr. Don Slack, MPD is making changes to the way that ALS and BLS providers perform CPR. Overview: CPR quality has a dramatic impact on pt survival when done according to these guidelines. Minimal breaks in compressions, full chest recoil, adequate compression depth and adequate compression rate are all components of CPR that an increase survival from sudden cardiac arrest. Together these components go together to create High Performance CPR (HP CPR). Roles: As a rule for the unconscious, unresponsive, pulseless patient the FIRST person to the patient starts compressions. SECOND person does defibrillation (If there are only 2 responders to begin with, ventilations should begin after the rhythm analysis and shock if indicated). THIRD person should start ventilating the patient, placing a King Airway as soon as is practical. A timekeeper needs to be assigned to ensure high quality CPR, minimal interruption and help track the ALS interventions. Principles of HP CPR 1. EMT’s own CPR!! 2. Minimize interruption in CPR at all times, use a timekeeper 3. Ensure proper depth of compressions (>2 inches) 4. Ensure full chest recoil/decompression 5. Ensure proper chest compression rate (100-120/min) 6. Rotate compressors at least every 2 minutes 7. Do not interrupt compressions to ventilate patient, even if an advanced airway is not placed 8. Hands off the chest only during analysis and shock delivery, hover hands over chest during shock delivery and be ready to resume compressions 9. -

Small Adult CPR-2 Bag with Litesaver Manometer Brochure

ORDERING INFORMATION Your Need ... Our Innovation® O Manometer 2 Detector 2 AerosolTubing Reservoir Infant Cushion Mask Expandable Large Bore Color-Coded Mask PEEP w/Filter StatCO Manometer LiteSaverTiming Light with CPR (Synthetic Rubber) CPR-2 (PVC) Light Blue Oxygen Bag Reservoir (22mm) Adult Cushion Mask SmallAdult Cushion Mask with Flange #3 Pediatric Cushion Mask Child Cushion Mask PEEP Valve Pop-Off Dark Blue Oxygen Reservoir 0-60 cm H PART # OTHER #10-56402 X X X X X X #10-56403 X X X X #10-56404 X X X X X #10-56411 X X X X #10-56412 X X X X X #10-56423 X X X X X X #10-56424 X X X X X X CPR-2 Small Adult Bag with Manometer #10-56432 X X X X X #10-56435 X X X X X X X #10-56437 X X X X #10-56438 X X X X X #10-56440 X X X X #10-58500 X X X X #10-58501 X X X X X #10-58502 X X X X X #10-58503 X X X X X X #10-58506 X X X X X X #10-58507 X X X X X #10-58509 X X X X X #10-58512 X X X X X X X #10-55901 X X X #10-55904 X X X #10-55907 X X X #10-55909 X X X X #10-55910 X X X X #10-55912 X X X #10-55913 X X X X X X No lock clip #10-55915 X X X X X #10-55916 X X X #10-55917 X X X X X #10-55918 X X X X X X #10-55922 X X X X X X X #10-55923 X X X X #10-55924 X X X X X #10-55928 X X X #10-58400 X X X X #10-55365 LiteSaver Manometer Assy 20/Box 0-60 cm H2O, Adult Frequency 10 BPM #10-55366 LiteSaver Manometer Assy 20/Box Assembly 0-60 cm H2O In-Line Tee Right Orientation, Adult Frequency 10 BPM #10-55367 LiteSaver Manometer Assy 20/Box Assembly 0-60 cm H2O In-Line Tee Left Orientation, Adult Frequency 10 BPM = CPR-2 Small Adult Bags *References Can EMS Providers Provide Appropriate Tidal Volumes in a Simulated Adult-sized Patient with a Pediatric-sized Bag-Valve-Mask? Journal Pre-hospital Emergency Care, Volume 21, 2017, Issue 1, Jeffery Siegler, MD, EMT-P, Melissa Kroll, MD, Susan Wojcik, PhD, ATC & Hawnwan Philip May, MD Avoid Airway Catastrophes on the Extremes of Minute Ventilation, Acepnow.com, January 20, 2015, Richard M. -

Capnography (ILS/ALS)

Capnography (ILS/ALS) Clinical Indications: 1. Capnography shall be used as soon as possible in conjunction with any airway management adjunct, including endotracheal, Blind Insertion Airway Devices (BIAD) or Bag Valve Mask (BVM). 2. Capnography should also be used on all patients treated with CPAP or epinephrine for respiratory distress. 3. Acute respiratory distress. 4. Assisted ventilations. 5. Sustained altered mental status. Procedure: 1. Attach capnography sensor to the BIAD, endotracheal tube, or oxygen delivery device. 2. Note CO2 level and waveform changes. These will be documented on each respiratory failure, cardiac arrest, or respiratory distress patient. 3. The capnometer shall remain in place with the airway and be monitored throughout the prehospital care and transport. 4. Any loss of CO2 detection or waveform indicates an airway problem and should be documented. 5. The capnogram should be monitored as procedures are performed to verify or correct the airway problem. 6. Document the procedure and results on/with the Patient Care Report (PCR) and the Airway Evaluation Form. 7. In all patients with a pulse, an ETCO2 >20 is anticipated. In the post-resuscitation patient, no effort should be made to lower ETCO2 by modification of the ventilatory rate. Further, in post- resuscitation patients without evidence of ongoing, severe bronchospasm, ventilatory rate should never be < 6 breaths per minute. 8. In the pulseless patient, and ETCO2 waveform with an ETCO2 value >10 may be utilized to confirm the adequacy of an airway to include BVM and advanced devices when Sp02 will not register. Critical Comment: • When CO2 is NOT detected, three factors must be quickly assessed : 1. -

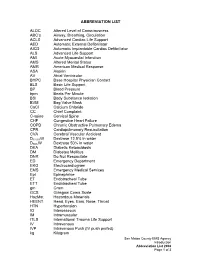

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

Information on Defibrillation and Ventilation with the LUCAS® Chest Compression System

® LUCAS CHEST COMPRESSION SYSTEM Information on Defibrillation and Ventilation with the LUCAS® Chest Compression System The goal when using the LUCAS device is to provide effective, After Defibrillation consistent, and uninterrupted chest compressions. When an After the shock is delivered it is important to verify the position of the interruption to chest compressions occurs, the patient’s coronary suction cup to see it has not moved out of place. This is easier to do perfusion pressure (CPP) drops rapidly. CPP is the measure of the if an ink marker line was marked where the suction cup was originally pressure that drives blood flow through the coronary arteries to the positioned on the patient. Readjust as necessary. heart muscle. The heart normally maintains a CPP of 60 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) or more. During cardiac arrest, the CPP drops dramatically, threatening the heart muscle’s blood supply. As it can take Oxygenation with Ventilation some time to build up CPP again, interruptions to chest compressions should be minimized. To supply adequate concentrations of oxygen in the blood, ensure the patient is properly ventilated. Ventilations should be provided in The current American Heart Association Guidelines emphasize conjunction with mechanical chest compressions. Interruptions to 1 minimizing interruptions when delivering high quality CPR: chest compressions should be minimized to maintain the level of • Minimize pre- and post-shock pauses (class I), oxygen delivered to tissues. During the first few minutes of sudden cardiac arrest, chest compressions to improve blood flow have been • Pause compressions for less than 10 seconds when delivering two shown to be more important than ventilations because oxygen blood breaths (class IIa), levels remain high initially.4 • Maximize the time with chest compressions (class IIb). -

The Golden Hour > How Time Shapes Airway Management > by Charlie Eisele,BS,NREMT-P

September 2008 The A supplement to JEMS (the Journal of Emergency Medical Services) Conscience of EMS JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES Sponsored by Verathon Inc. ELSEVIER PUBLIC SAFETY The Perfect View How Video Laryngoscopy Is Changing the Face of Prehospital Airway Management A supplement to September 2008 JEMS, sponsored by Verathon Inc. 4 Foreword > To See or Not to See, That Is the Question > By A.J.Heightman,MPA,EMT-P 5 5 The Golden Hour > How Time Shapes Airway Management > By Charlie Eisele,BS,NREMT-P 9 The Video Laryngoscopy Movement > Can-Do Technology at Work > By John Allen Pacey,MD,FRCSc 11 ‘Grounded’ Care > Use of Video Laryngoscopy in a Ground 11 EMS System: Better for You, Better for Your Patients > By Marvin Wayne,MD,FACEP,FAAEM 14 Up in the Air > Video Laryngoscopy Holds Promise for In-Flight Intubation > By Lars P.Bjoernsen,MD,& M.Bruce Lindsay,MD 16 16 The Military Experience > The GlideScope Ranger Improves Visualization in the Combat Setting > By Michael R.Hawkins,MS,CRNA 19 Using Is Believing > Highlights from 72 Cases Involving Video Laryngoscopy at Martin County (Fla.) Fire Rescue > By David Zarker,EMT-P 21 Teaching the Airway > Designing Educational Programs for 21 Emergency Airway Management > By Michael F.Murphy,MD; Ron M.Walls,MD; & Robert C.Luten,MD COVER PHOTO KEVIN LINK Disclosure of Author Relationships: Authors have been asked to disclose any relationships they may have with commercial supporters of this supplement or with companies that may have relevance to the content of the supplement. Such disclosure at the end of each article is intended to provide readers with sufficient information to evaluate whether any material in the supplement has been influenced by the writer’s relationship(s) or financial interests with said companies. -

Resuscitation and Defibrillation

AARC GUIDELINE: RESUSCITATION AND DEFIBRILLATION AARC Clinical Practice Guideline Resuscitation and Defibrillation in the Health Care Setting— 2004 Revision & Update RAD 1.0 PROCEDURE: signs, level of consciousness, and blood gas val- Recognition of signs suggesting the possibility ues—included in those conditions are or the presence of cardiopulmonary arrest, initia- 4.1 Airway obstruction—partial or complete tion of resuscitation, and therapeutic use of de- 4.2 Acute myocardial infarction with cardio- fibrillation in adults. dynamic instability 4.3 Life-threatening dysrhythmias RAD 2.0 DESCRIPTION/DEFINITION: 4.4 Hypovolemic shock Resuscitation in the health care setting for the 4.5 Severe infections purpose of this guideline encompasses all care 4.6 Spinal cord or head injury necessary to deal with sudden and often life- 4.7 Drug overdose threatening events affecting the cardiopul- 4.8 Pulmonary edema monary system, and involves the identification, 4.9 Anaphylaxis assessment, and treatment of patients in danger 4.10 Pulmonary embolus of or in frank arrest, including the high-risk de- 4.11 Smoke inhalation livery patient. This includes (1) alerting the re- 4.12 Defibrillation is indicated when cardiac suscitation team and the managing physician; (2) arrest results in or is due to ventricular fibril- using adjunctive equipment and special tech- lation.1-5 niques for establishing, maintaining, and moni- 4.13 Pulseless ventricular tachycardia toring effective ventilation and circulation; (3) monitoring the electrocardiograph and recogniz- -

Pediatric Trauma and Critical Care Provides Six (6) Hours of Continuing Education Credit

PEDIATRIC TRAUMA AND CRITICAL CARE PROVIDES SIX (6) HOURS OF CONTINUING EDUCATION CREDIT AGENDA 0800-0830 Registration 0830-0930 Transport Pearls for the Neonate Patty Duncan, BSN, RNC 0930-0940 Break 0940-1140 Pediatric Airway and Prehospital Golden Hour Dave Duncan, MD 1145-1215 Lunch 1215-1315 State of the Art EMS Protocols are Created, Not Born That Way Paul S. Rostykus, MD, MPH, FAEMS 1315-1325 Break 1325-1525 Pediatric Trauma Heather Summerby, RN 1525-1530 Evaluation Transport Pearls for the Neonate Patty Duncan There are not many careers where your decisions and interactions can positively impact the life of a human for up to 80 plus years. Dr. Stephen Butler PEARLS OF NEONATAL TRANSPORT FROM A 35 YEAR NICU RN PATTY DUNCAN BSN RNC PATTY DUNCAN BSN RNC • ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT COORDINATOR • ALS NICU TRANSPORT COORDINATOR • ASSISTANT NURSE MANAGER 61 BED LEVEL 3 NICU • STABLE INSTRUCTOR • NRP INSTUCTOR NICU TRANSPORT TEAM • VIA GROUND, FIXED WING AND ROTOR • SERVE 27 COUNTIES IN NORTHERN CA • 3 OUT OF HOUSE TRANPORT ISOLETTE CONTAIN CONV VENT HFJV NITRIC OXIDE ACTIVE COOLING TECOTHERM BCPAP THE NEONATE-WHY THEY ARE SPECIAL • OF, RELATING TO ,OR AFFECTING THE NEWBORN AND ESPECIALLY THE HUMAN INFANT DURING THE FIRST MONTH AFTER BIRTH • MERRIAM-WEBSTER Large surface area compared to size keep them warm (BSA is 3X greater than adult) Correct ventilation is the key to solving most issue be smart Glucose is their energy source - keep them sweet NEONATES: MASTERS OF DISGUISE KEY = TREAT THE SYMPTOM! • Tachypnea: the most common symptom! • Respiratory Distress Syndrome • Transient tachypnea of the newborn, Hyaline Membrane Disease, pneumothorax, pneumonia • Sepsis-bacterial, virus • Cardiac-ductal dependent vs non ductal dependent • Metabolic Acidosis • Hypoglycemia, • Hypothermia TREAT THE SYMPTOMS! THE DIAGNOSIS WILL FOLLOW (MAYBE) S.T.A.B.L.E. -

FIRST AID QUICK SHEET- Airway and Breathing

FIRST AID QUICK SHEET Airway and Breathing After you have checked to make sure the scene is safe and put on gloves to protect yourself (Danger) and checked if the patient is responsive (Response), if you find the patient is not responding, you should think: ABC. First check for an Airway and Breathing. Instructions for the A and B steps of the DR. ABC acronym for first aid priorities are below: How to Adjust Someone’s Airway (A): 1. Gently swipe the mouth with one finger to ensure that no objects are blocking the airway. 2. Place two fingers under the casualties chin and one hand on the forehead. 3. Gently lift the chin with two fingers, removing the tongue from the back of the throat. 4. If transport is delayed, roll the casualty onto their side in the recovery position to allow fluids to drain from the mouth Note: If someone is able to speak, their airway is open. Breathing (B): 1. Always remember to look, listen, and feel when checking for breathing. 2. LOOK to see the chest rise and fall. 3. LISTEN to hear breath sounds. 4. Place one hand on the stomach and FEEL for breathing movement and FEEL beneath the nose for air movement. After you have secured an airway and checked for breathing, you may move on to check for bleeding in the C (circulation) step of DR. ABC. *Please be safe and practice first aid at your own risk. LFR International is not liable for injuries resulting from any first aid attempts. .