Sussex Industrial History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIAS Newsletter 061.Pdf

SUSSEX INDUSTRIAL HISTORIC FARM BUILDINGS GROuP ~T~ ARCHAEOLOGY SOCIETY Old farm buildings are among the most conspicuous and pleasing features of the ~ Rcgistcral ChJri'y No_ 267159 traditional countryside. They are also among the most interesting, for they are valuable --------~=~------ and substantial sources of historical knowledge and understanding. NEWSLETTER No.6) ISSN 0263 516X Although vari ous organisations have included old farm build-iogs among their interests there was no s ingle one solely concerned with the subject. It was the absence of such an Price lOp to non-members JANUAR Y 1989 organisation which led to the establishment of the Group in 1985. Membership of the Group is open to individuals and associations. A weekend residential conference, which inc ludes visits to farm buildings of historical interest, is held CHIEF CONTENTS annually. The Group also publishes a Journal and issues regular newsletters to members. Annual Reports - Gen. Hon. Secretary, Treasurer If you wish t o join, send your subscription (£5 a year for individuals) to the Area Secretaries' Reports Secretary, Mr Roy Bridgen, Museum of English Rural Life, Box 229, Whiteknights, Reading In auguration of Sussex Mills Group RG2 2AG. Telephone 0731! 875123. New En gland Road railway bridges - Brighton Two Sussm: Harbours in the 18th century MEMBERSHIP C HANGES Brighton & Hcve Gazette Year Book New Members Mrs B.E. Longhurst 29 Alfriston Road, Worthing BN I4 7QS (0903 200556) '( II\R Y DATES Mrs E. Riley-Srnith E\rewhurst, Loxwood, Nr. Bi lill1 gshurst RHI/i OR J ( O~03 75235 Sunday, 5th Ma rch. Wo rking vi sit to Coultershaw Pump, Pe tworth. -

1 No 183 Sept 2011

No 183 Sept 2011 1 www.sihg.org.uk Three Very Different Wealden Iron Furnaces by Alan Crocker On 23 July I attended the AGM of the Wealden Iron Research Group (WIRG) at the Rural Life Centre (RLC), Tilford. These meetings are usually held in Sussex but this year the event came to Surrey, as the RLC has recently constructed a half -scale replica of a Wealden iron blast furnace and forge, complete with waterwheel, bellows and tilt hammer. The meeting started at 1030 with coffee and biscuits and then the Director of the RLC, Chris Shepheard, a former Chairman of SIHG, talked about the formation of the museum, its activities and the enormous amount of work done by volunteers, known as ‘Rustics’. A group of these, headed by Gerald Baker, has been responsible for raising funds for and constructing the replica furnace in a former pig sty on the museum site. After lunch in the RLC Restaurant, Gerald operated the furnace for our party. There is no stream flowing through the museum site so the waterwheel, which is overshot and 6 feet in hammer. The Rustics had lit a wood fire in diameter, has to be turned by circulating water the kiln but for several reasons it was not with an electrically powered pump. One end of its possible to demonstrate smelting and shaft operates paired bellows which force air into forging. This was partly because of safety the base of the furnace through a hole known as a regulations, partly because charcoal and iron tuyere. The other end of the shaft operates a trip ore are not yet available and partly because with a small-scale furnace the high temperatures required may not be attainable. -

The Association for Industrial Archaeology

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY 1o^7 WINTER 1 998 THE BULLETIN OF THE ASSOCIANON FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY 95 oence FREE TO MEMBERS OF AIA South Atlantic lA o Napier engineering o Honduran mines o TICCIH piers o Ferranti o Wey barges o education o regional news Honduran mining complexes of the sixteenth century Pastor G6mez this period, which was also the time when mining exploitation started. INDUSTRIAL This anicle (translated by Elanca Martin) outlines Mining activity was at first usually limited to HAEOLOG the historical background and potential value of washing gold in alluvial deposits, where forced studying the sixteenth-century industrial native labourers used rudimentary technology. The NEWS rO7 archaeological heritage of two Honduran districts: original Spanish conquerors started to look for Santa Lucia Tegucigalpa and San Lorenzo other income sources when alluvial deposits Winter 1998 Guazucardn. both of which have documented became over-exploited and the indiginous soutces. population, already declining, came under the President protection of the Spanish Crown. Dr Michael Hanison In November 1995, the Honduran Institute of The discovery of silver deposits near 19 Sandles Close, The Ridings, Droitwich Spa WR9 8RB Anthropology & History (lnstituto Hondureno de Comayagua (then the seat of colonial government) Vice-President Antropologla e Historia) carried out archaeological marked the beginning of industrial mining Dr Marilyn Palmer School of Archaeological Studies, The University, Leicester surveys in San Lorenzo Guazucardn, in the exploitation in the country. lt was in 1569 that the LEl 7RH municipality of Ojojona, where a colonial mining first silver minerals in the district of San Lorenzo Treasurer complex was found. -

Charlwood Parish Council

CHARLWOOD PARISH COUNCIL Serving the communities of Charlwood, Hookwood and Norwood Hill www.charlwoodparishcouncil.gov.uk e-mail: [email protected] Draft Minutes of Full Council Meeting held on 16th September 2019 at 8pm Venue Charlwood S&CC Attending Penny Shoubridge (PS), Carolyn Evans (CE), Nick Hague (NH), Walter Hill (WH), Richard Parker (RP), Howard Pearson (HP), Lisa Scott (LS), Trevor Stacey (TS). Clerk Trevor Haylett Also Jan Gillespie, Hilary Sewill, Peter Suchy, Jackie Tyrrell Attending Item 1 Apologies – James O’Neill, County Councillor Helyn Clack. 2 Declaration of Interest – None 3 Minutes – Nick Hague proposed and Howard Pearson seconded that the Minutes of the Meeting held on 15th July be approved. This was agreed and the Minutes duly signed. 3.1 Chairman’s Comments – Penny Shoubridge said that it had been decided to move Public Questions down the Agenda so the item came after the reports of the Planning & S&A Committees. This was so the public could raise matters after hearing those reports. PS also explained that asylum seekers had again been placed at the Russhill Hotel for a short period. The Home Office was providing transport for them and hi-vis jackets so they would be safe when walking into the village. 4 Report of the Planning and Highways Committee -- 4.1 Planning Comments on applications to week ending 6th September - These had been circulated and NH proposed, with PS seconding, that they be accepted. That was approved. The Committee had given support to the travel plan submitted by Charlwood School and had advised that it could be enhanced by the repainting of the parking-zone lines outside the school gates. -

Mill Memories

Issue 2 February 2008 Mill Memories The Newsletter of the Friends of the Mills Archive A new opportunity; a new challenge The Heritage Lottery Fund told us in January that they have awarded us £49,800 for our new “Frank Gregory Online” project! Issue 1 of Mill Memories featured our successful Kent Millers’ Special features: Tales venture, also supported by the HLF and launched at Postcards as Cranbrook windmill last September. That 2-year undertaking historical records allowed us to catalogue more than 8000 images and documents Chiltern mill on Kent mills and put them on the Internet for all to see. drawings This new commission is much more ambitious and underlines Frank Gregory and how the Mills Archive works with other bodies to protect our Kenneth G Farries milling heritage. Frank’s enormous, largely disorganised collection is stored at the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum at Derek Ogden’s Singleton, West Sussex, but ever since it was left to them almost millwrighting files 10 years ago, it has not been available to the public. We intend over the next three years to remedy that, sorting the material, labelling, indexing and scanning as needed, before Inside this issue: carefully storing the mill items in archival enclosures. We will display all the best documents and images on our website along Collections in Practice 2 with detailed finding aids for the other objects. In time the News from the Archive 3 originals will be returned to Singleton, but we will keep copies of the most interesting matter in Reading. Friends’ Forum 8 People Pages 10 Bookshelf 12 Visiting the Archive 13 Although this is our fourth successful Lottery bid, they do not pay our rent, storage and other costs, which is why the support of the Joining the Friends 14 Friends is so highly valued. -

Gps Coördinates Great Britain

GPS COÖRDINATES GREAT BRITAIN 21/09/14 Ingang of toegangsweg camping / Entry or acces way campsite © Parafoeter : http://users.telenet.be/leo.huybrechts/camp.htm Name City D Latitude Longitude Latitude Longitude 7 Holding (CL) Leadketty PKN 56.31795 -3.59494 56 ° 19 ' 5 " -3 ° 35 ' 42 " Abbess Roding Hall Farm (CL) Ongar ESS 51.77999 0.27795 51 ° 46 ' 48 " 0 ° 16 ' 41 " Abbey Farm Caravan Park Ormskirk LAN 53.58198 -2.85753 53 ° 34 ' 55 " -2 ° 51 ' 27 " Abbey Farm Caravan Park Llantysilio DEN 52.98962 -3.18950 52 ° 59 ' 23 " -3 ° 11 ' 22 " Abbey Gate Farm (CS) Axminster DEV 50.76591 -3.00915 50 ° 45 ' 57 " -3 ° 0 ' 33 " Abbey Green Farm (CS) Whixall SHR 52.89395 -2.73481 52 ° 53 ' 38 " -2 ° 44 ' 5 " Abbey Wood Caravan Club Site London LND 51.48693 0.11938 51 ° 29 ' 13 " 0 ° 7 ' 10 " Abbots House Farm Goathland NYO 54.39412 -0.70546 54 ° 23 ' 39 " -0 ° 42 ' 20 " Abbotts Farm Naturist Site North Tuddenham NFK 52.67744 1.00744 52 ° 40 ' 39 " 1 ° 0 ' 27 " Aberafon Campsite Caernarfon GWN 53.01021 -4.38691 53 ° 0 ' 37 " -4 ° 23 ' 13 " Aberbran Caravan Club Site Brecon POW 51.95459 -3.47860 51 ° 57 ' 17 " -3 ° 28 ' 43 " Aberbran Fach Farm Brecon POW 51.95287 -3.47588 51 ° 57 ' 10 " -3 ° 28 ' 33 " Aberbran Fawr Campsite Brecon POW 51.95151 -3.47410 51 ° 57 ' 5 " -3 ° 28 ' 27 " Abererch Sands Holiday Centre Pwllheli GWN 52.89703 -4.37565 52 ° 53 ' 49 " -4 ° 22 ' 32 " Aberfeldy Caravan Park Aberfeldy PKN 56.62243 -3.85789 56 ° 37 ' 21 " -3 ° 51 ' 28 " Abergwynant (CL) Snowdonia GWN 52.73743 -3.96164 52 ° 44 ' 15 " -3 ° 57 ' 42 " Aberlady Caravan -

01793 846222 Email: [email protected]

Science Museum Library and Archives Science Museum at Wroughton Hackpen Lane Wroughton Swindon SN4 9NS Telephone: 01793 846222 Email: [email protected] SIMNS A guide to the Simmons Collection of research records relating to British windmills and watermills Compiled by H. E. S. Simmons (1901-1973) SIMNS A guide to the Simmons Collection of research records relating to British windmills and watermills List Contents BOX DESCRIPTION PAGE (original list) General note on the collection, I including access and copying Abbreviations used in the survey Iii notes SIMNS Survey notes: windmills 1 1 SIMNS Survey notes: watermills 4 2 SIMNS Miscellaneous notes 8 3 SIMNS Maps (Simmons own numbering) 9 4 SIMNS Maps (unnumbered by Simmons) 14 5 SIMNS Photographs: windmills 24 (note 6 p.23) SIMNS Photographs: watermills 47 (note 7 p.23) SIMNS General records and records of mill 54 8 photography Introduction Herbert Edward Sydney Simmons was born on 29th September 1901 in Washington, Sussex. He worked for many years as a civil servant in the Ministry of Defence; during the Second World War he served in the Royal Air Force, stationed in Warwickshire and East Anglia. He died on 26th October 1973 at his home in Shoreham-by-Sea, Sussex. Simmons had a lifelong interest in windmills and watermills. During more than 40 years of private research, he visited many mill sites and consulted a wide range of documentary sources, including fire insurance records, local newspapers, directories and maps. He also exchanged information with other mill enthusiasts and thus gathered further information on those mills he was unable to visit. -

Sussex Industrial Archaeology Sooety

SUSSEX INDUSTRIAL MEMBERSHIP CHA'lCES ARCHAEOLOGY SOOETY R.epter<d Chuity No. 267159 Ne~ Life Member ISSN 0263 516 X A. G. Ste',;ens, 26 Lorna Road, Hove, BN3 3EN NEWSLETTER NO. 43 New Memcers JULy 1984 A.E. Baxter, 11 Milton Street, Worthing, \-lest Sussex. EN'1 3NE (Worthing 203058) M.S. Davis, 73 Islingword Street, Brighton, East Sussex. BN2 2US CHIEF CONTENTS J.R. Elliot, 1 Hammer Cottages, Chequer Lane, Bosham, Chichester, POla 8EL (Bosham 572450) New Publication: I.A. of Sussex - A Field Guide S.I.A.S. E.S.C.C. :~oc al Government Unit, So~thover House, Sou ~ hover Road, Lewes, BN7 lYA , Mathematical Tiles Galore E.W. O'Shea (Lewes 5400, Ext.590) Council for British Archaeology Conference E. T. C. Harris, 18 Sergison Road, HaY..Iards Heath, West Sussex. RH 16 lH>\ 13th October, 1984 (Haywards Heath 451466) P. ;". Pannett, 3 Forest View, Hailsharn, East Sussex. BN27 3ET (Hailsham 840481 ) ( roRTIiCCMING VISITS Dr. R.C. Riley, 48 Maplehurst Road, Chichester, West Sussex P019 4RP . (Chichester 528635) 23rd September, Saturday 2.00 p.m. Another 'get-together' with the East Kent Mrs. A.C. Riley, 48 Maplehurst Road, Chichester, West Sussex. PC19 4RP Mills Croup in the Lec~ure Room of the Public Library, Tunbridge WelL~. (Chichester 528635) PUBLICATIONS Ch3nges of Address A New Publication M. Brunnarius, 30 Chanctonbury Road, Burgess Hill, West Sussex. RH15 9i:;Y Wi th this Newsletter it is hoped will be enclosed a leaflet publicising an R.H. Crook, 6 Anni ngton Road, Eastbourne, BN22 8NG ( East ~o urne 2905~) 0.1". -

1 No 198 Mar 2014

No 198 Mar 2014 1 www.sihg.org.uk Puttocks Charabanc Outing 1911 Dennis Brothers Motor Vehicles across the Centuries, see page 5 Dart Midi-bus 2004 Newsletter 198 March 2014 2 Contents 2 Notices 3 Diary 27 March 2014 - 31 May 2014 4 Venues, Times & Contacts 5 Dennis Brothers Motor Vehicles by John Dennis, Grandson of founder & Roger Heard, former Director report by Gordon Knowles 6 Iron Age long-handled combs - Controversial Artefacts! by Glenys Crocker 7 Industrial Archaeology Review Vol. 35 No. 2 November 2013 report by Gordon Knowles 8 Alexander Raby, Downside Mill and Coxes Lock Mill and their place in the Industrial Revolution by Richard Savage, report by Glenys Crocker Reports & Notices Details of meetings are reported in good faith, but information may become out of date. Please check before attending. SIHG Visits, Details & Updates at www.sihg.org.uk SERIAC 2014 South East Regional Industrial Archaeology Conference " Bricks, Bugs & Computers" Saturday 12 April 2014, hosted by Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society with the help of Croydon Natural History & Scientific Society & Subterranea Britannica at Royal Russell School, Croydon Programme/application form can be downloaded from www.sihg.org.uk The deadline for submitting copy for the next Newsletter is 10 May 2014 Submissions are accepted in typescript, on a disc, or by email to [email protected]. Anything related to IA will be considered. Priority will be given to Surrey-based or topical articles. Contributions will be published as soon as space is available. Readers are advised that the views of contributors are not necessarily the views of SIHG. -

Parish Folders

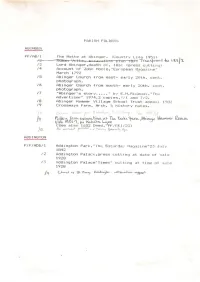

PA RISHFD LII)ElP; B ABINGER PF/AB/:l TIts Mo11e at Ab i nger". (Gaun t r•y Li-+ e 1951) , ROAa.n Vi 1 1a ^• o^; c:inn—rji an—j:D77 4o Lord Abinqer, death O'S-, 1861 (press cuttir.q) /4 Account o-f John Hool e, "European l>lagaz :i. rve" March 1792 /5 Abinger GhurcEi from east- eahly 20th„ cent- photograph» /6 Abinger Church from south- early 20th, cent, photograph. /7 "Abinger's story.,,,," by E,H.Rideout,"The Advertiser" 1974,2 copies,7/1 and 7/2. /a Abinger Ha mmer Village Sc In oo I Tr u s t a p p e a 1 198 2 /9 Crossways Farm, ArcEi, Fiistory notes. / /f- ,4 fJCvU TW ^<v.Vw<s VWa/uvvvaHv IZowajxa. /" i(jij L>AVNe. i: See a 1so 1652 Deed , "^PF / RE I/ 2.51 /(^ ADDINI3TDN P/F/ADD/1 Ad d i n g t o n Park," "i h s S a t u r d a; / -ila g a z .in e " 2 3 J111 y 1842 /2 Addington Palace,press cutting at date of e,..-:) | e 1928 Add i ngton Pal ace"Ti mes" c u 11 i n g <3. t t. i me o f 1928 h P A R J.S H F L.) I... r>£ R S ALBURY PF/ALB/l (Altau.ry Estate sale, Transferred to Ml 4/ALEt''9) /2 "A visit to Albu.ry Cathedral via St,. Martha'-s" (Catholic and Apostolic Church), incomplete press cutting undated,c.1855 /3 "The Parish, the Church and its Minister"by "The Clerical RoverA1bury section (see also PF/GFD/300) 1878? /4 Consecration o-f Parish Church with new chancel, press cuttinq ,undated, (19tl-K centurv ?) /5 William Oughtred, press cutting,undated, /6 Death ot Henry Drummond, preess cutting 1860 /7 Henry Drummond, obituary,"The Star" 1860 /8 Henry Drummond, Tuneral,press cutting 3n3„1860 /9 ditto di tto another pres;;s ci..i.11 i 11a1B60 /lO Henry Drummond,death "West Surrey Times"25.2,1860 /11 Albury Cliurch, incomplete 19th, century press c y 11i n g , u.n d a t e d, /12 S E? r Vi c e a t A1 fc) u r y C; I-ua r c I•) w i. -

Charlwood Bluebells.Pdf

point your feet on a new path Charlwood Bluebell Walk Distance: 4½ km=2¾ miles easy walking with some steep banks Region: Surrey Date written: 11-mar-2012 Author: Schwebefuss Date revised: 28-apr-2015 Refreshments: Charlwood Last update: 2-jun-2021 Map: Explorer 146 (Dorking) but the map in this guide should be sufficient Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Woodland, bluebells, village, church, pub In Brief This circular walk finds some areas of spectacular bluebell woods in south- east Surrey, near the Sussex border. This walk takes some unusual paths through the wood where you may be one of the few people to witness some of the best hidden displays. The best time to see the bluebells is usually mid-to-late April. There are no nettles or undergrowth. Normally any sensible footwear is ? fine but if it has been wet you will encounter some muddy patches where good boots or wellies will be needed. Your dog will be in good company. The walk begins in Charlwood village, postcode RH6 0DS near the church and the Half Moon pub. The lane near the pub is one-way and is a tight right turn (if coming from the north) from The Street. It tends to get full up towards lunchtime and on Sundays, in which case there are spaces in the village. For more details, see at the end of this text ( Getting There ). -

Rpsgroup.Com

Table 4.7: Summary of known Romano-British remains within Updated Scheme Design area Romano-British Location Significance Potential for currently settlement sites unknown sites 1 – RPS 114 (possible Horley Land Unknown Moderate - high (includes occupation area) Farm, now (possibly landscape and industrial Gatwick car park Medium) elements) east of railway 2 – RPS 405 – three Land east of Low north-south aligned London Road field-boundaries of possible RB date Saxon (AD 410 – AD 1066) Local Settlement 4.59 Settlements of early Saxon date are rarely identified in the Weald, despite place-name evidence that indicates encroachment into the Wealden forest for farming or pannage. By the late Saxon period the Weald had been sparsely settled. There are no Anglo-Saxon sites noted on the HERs/EH Archives within the updated scheme design area or the wider Study Area. However, a gully traced for about 20 m at the Gatwick North West Zone produced three sherds of Saxon pottery (Framework Archaeology 2001, 13). 4.60 The presence of at least late Saxon occupation is implicit in the local place-name evidence including Gatwick itself. However, the relatively large-scale archaeological excavations at Horley (ASE 2009; ASE 2013) and Broadbridge Heath (Margetts 2013) failed to identify archaeological evidence for Saxon settlement and it is possible that such evidence would also be elusive within the updated scheme design area. The place-names of most of the principal villages and hamlets of the wider Study Area reflect clearances in woodland. For example the Old English place-name ‘Charlwood’ emphasizes the largely wooded nature of the area in the Anglo-Saxon period, meaning ‘Wood of the freemen or peasants’ (Mills 1998).