Mon Gastrointestinal Causes of Right Lower Quadrant Abdominal Pain at Multidetector CT1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Herbivore Digestive System Buffalo Zebra

The Herbivore Digestive System Name__________________________ Buffalo Ruminant: The purpose of the digestion system is to ______________________________ _____________________________. Bacteria help because they can digest __________________, a sugar found in the cell walls of________________. Zebra Non- Ruminant: What is the name for the largest section of Organ Color Key a ruminant’s Mouth stomach? Esophagus __________ Stomach Small Intestine Cecum Large Intestine Background Information for the Teacher Two Strategies of Digestion in Hoofed Mammals Ruminant Non‐ruminant Representative species Buffalo, cows, sheep, goats, antelope, camels, Zebra, pigs, horses, asses, hippopotamus, rhinoceros giraffes, deer Does the animal Yes, regurgitation No regurgitation regurgitate its cud to Grass is better prepared for digestion, as grinding Bacteria can not completely digest cell walls as chew material again? motion forms small particles fit for bacteria. material passes quickly through, so stool is fibrous. Where in the system do At the beginning, in the rumen Near the end, in the cecum you find the bacteria This first chamber of its four‐part stomach is In this sac between the two intestines, bacteria digest that digest cellulose? large, and serves to store food between plant material, the products of which pass to the rumination and as site of digestion by bacteria. bloodstream. How would you Higher Nutrition Lower Nutrition compare the nutrition Reaps benefits of immediately absorbing the The digestive products made by the bacteria are obtained via digestion? products of bacterial digestion, such as sugars produced nearer the end of the line, after the small and vitamins, via the small intestine. intestine, the classic organ of nutrient absorption. -

Sporadic (Nonhereditary) Colorectal Cancer: Introduction

Sporadic (Nonhereditary) Colorectal Cancer: Introduction Colorectal cancer affects about 5% of the population, with up to 150,000 new cases per year in the United States alone. Cancer of the large intestine accounts for 21% of all cancers in the US, ranking second only to lung cancer in mortality in both males and females. It is, however, one of the most potentially curable of gastrointestinal cancers. Colorectal cancer is detected through screening procedures or when the patient presents with symptoms. Screening is vital to prevention and should be a part of routine care for adults over the age of 50 who are at average risk. High-risk individuals (those with previous colon cancer , family history of colon cancer , inflammatory bowel disease, or history of colorectal polyps) require careful follow-up. There is great variability in the worldwide incidence and mortality rates. Industrialized nations appear to have the greatest risk while most developing nations have lower rates. Unfortunately, this incidence is on the increase. North America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand have high rates for colorectal neoplasms (Figure 2). Figure 1. Location of the colon in the body. Figure 2. Geographic distribution of sporadic colon cancer . Symptoms Colorectal cancer does not usually produce symptoms early in the disease process. Symptoms are dependent upon the site of the primary tumor. Cancers of the proximal colon tend to grow larger than those of the left colon and rectum before they produce symptoms. Abnormal vasculature and trauma from the fecal stream may result in bleeding as the tumor expands in the intestinal lumen. -

Digestive System

Naziha Sultan Ahmed, BVMS, MSc Scientific degree (Assis. Prof.), Department of Anatomy College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2856-8277 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Naziha_Ahmed Anatomy | Part 18| 2nd year 2019 Digestive System Fixation of the liver (Ligaments of the liver): 1-Lesser omentum: consist of two parts: a/Hepatogastric ligament: connect between hepatic porta and lesser curvature of the stomach . b/Hepatoduodenal ligament: connect between hepatic porta and the cranial part of the duodenum. 2-Coronary ligament: connect between the parietal (diaphragmatic ) surface of liver, with the diaphragm and the caudal vena cava. 3-Falciform ligament: connect between the notch of round ligament in the liver and the sternal part of the diaphragm. 4-Round ligament: the residue (remnants) of the umbilical vein of the fetus. 5-Hepatorenal ligament: connect between the right lobe of liver and the right kidney. 6-Right & left triangular ligaments: connect between the dorsal border of right and left lobes of the liver and the diaphragm . Both ligaments continue medially with the coronary ligament. CouAnatomy | Digestive system | Assis. Prof. Naziha Sultan Ahmed Page | 1 The pancreas: Pancreas has V-shape. It consists of base and two limbs (right & left limbs). *In horse: large pancreas body perforated by portal vein and long left limb, with short right limb (because of large size of cecum in horse ). The horse pancreas has two ducts: 1-Chief pancreatic duct: opens with bile duct at the major duodenal papilla. 2-Accessory pancreatic duct: opens at the minor duodenal papilla. *In dog: pancreas notched by the portal vein. -

Nutrition Digestive Systems

4-H Animal Science Lesson Plan Nutrition Level 2, 3 www.uidaho.edu/extension/4h Digestive Systems Sarah D. Baker, Extension Educator Goal (learning objective) Pre-lesson preparation Youth will learn about the differences, parts and Purchase supplies (bread, soda, orange juice, functions between ruminant and monogastric diges- Ziploc baggies) tive systems. Make copies of Handouts 1, 2, and 3 for group Supplies Prepare bread slices Copies of Handout 1 “Ruminant vs Monogastric Make arrangements to do the meeting in a lo- Digestive System” make enough copies for group cation that has internet connection, tables, and Copies of Handout 2 “Ruminant Digestive System chairs – Parts and Functions” make enough copies for Read/review lesson group Watch video Copies of Handout 3 “Monogastric Digestive Sys- Test computer/internet connection and video be- tem – Parts and Functions” make enough copies fore meeting https://youtu.be/JSlZjgpF_7g for group Computer (may need speakers depending on facil- Lesson directions and outline ity and group size) Share the following information with the youth: Internet connection to view YouTube video The definition of digestion is the process of break- Slices of bread cut into 4 squares (each member ing down food by mechanical and enzymatic action in will need one square of bread) the stomach and intestines into substances that can be used by the body. The digestive system performs five Sandwich size Ziploc baggies (one bag for each major functions: member) 1. Food intake One, three-ounce cup for holding liquid (one cup for each member) 2. Storage 1 Liter of bottle of soda 3. -

(2012) 284-291 Morphological Studies On

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Journal of Advanced Veterinary Research (University Assiut, Egypt) Journal of Advanced Veterinary Research Volume 2 (2012) 284-291 Original Research Morphological Studies on the Postnatal Development of the Gut-associated Lymphoid Tissues of the Rabbit Cecum Abdelmohaimen M. Saleh Department of Anatomy and Histology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Assiut University, 71526 Assiut, Egypt. Abstract The macroscopic, morphometric, light and scanning electron microscopic structure of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of cecum were studied in the rabbits aged from birth to 16 weeks. The GALT were formed of lymph follicles covered by low columnar epithelium containing intraepithelial lymphocytes and leukocytes. They were concentrated at the ileocecal entrance (ileocecal patch) and in the blind end of the cecum vermiform appendix. In the ileocecal patch, GALT were in direct contact with the lumen, while those of the appendix were covered by the interval intestinal villi in young rabbits and mucosal folds in the adult rabbits. The lymphoid follicles of the ileocecal patch were composed of dome region and germinal center and were separated by narrow inter-follicular areas. Whereas, the lymphoid follicles of the appendix were composed dome region and germinal center in the newly born rabbits and up to the 2nd week of age, the follicles became composed of four different sites: dome region, germinal center, coronal area, and a wide interfollicular area between neighboring follicles. Morphome- trically; the dimensions of the lymphoid follicles of the cecal GALT increased in size with the advancement of the age. -

Colon and Rectum

AJC12 7/14/06 1:24 PM Page 107 12 Colon and Rectum (Sarcomas, lymphomas, and carcinoid tumors of the large intestine or appendix are not included.) C18.0 Cecum C18.5 Splenic flexure of C18.9 Colon, NOS C18.1 Appendix colon C19.9 Rectosigmoid C18.2 Ascending colon C18.6 Descending colon junction C18.3 Hepatic flexure of C18.7 Sigmoid colon C20.9 Rectum, NOS colon C18.8 Overlapping lesion of C18.4 Transverse colon colon SUMMARY OF CHANGES •A revised description of the anatomy of the colon and rectum better delineates the data concerning the boundaries between colon, rectum, and anal canal. Ade- nocarcinomas of the vermiform appendix are classified according to the TNM staging system but should be recorded separately, whereas cancers that occur in the anal canal are staged according to the classification used for the anus. •Smooth extramural nodules of any size in the pericolic or perirectal fat are con- sidered lymph node metastases and will be counted in the N staging. In contrast, irregularly contoured nodules in the peritumoral fat are considered vascular invasion and will be coded as transmural extension in the T category and further denoted as either a V1 (microscopic vascular invasion) if only microscopically visible or a V2 (macroscopic vascular invasion) if grossly visible. • Stage Group II is subdivided into IIA and IIB on the basis of whether the primary tumor is T3 or T4 respectively. • Stage Group III is subdivided into IIIA (T1-2N1M0), IIIB (T3-4N1M0), or IIIC (any TN2M0). INTRODUCTION The TNM classification for carcinomas of the colon and rectum provides more detail than other staging systems. -

Digestive System A&P DHO 7.11 Digestive System

Digestive System A&P DHO 7.11 Digestive System AKA gastrointestinal system or GI system Function=responsible for the physical & chemical breakdown of food (digestion) so it can be taken into bloodstream & be used by body cells & tissues (absorption) Structures=divided into alimentary canal & accessory organs Alimentary Canal Long muscular tube Includes: 1. Mouth 2. Pharynx 3. Esophagus 4. Stomach 5. Small intestine 6. Large intestine 1. Mouth Mouth=buccal cavity Where food enters body, is tasted, broken down physically by teeth, lubricated & partially digested by saliva, & swallowed Teeth=structures that physically break down food by chewing & grinding in a process called mastication 1. Mouth Tongue=muscular organ, contains taste buds which allow for sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami (meaty or savory) sensations Tongue also aids in chewing & swallowing 1. Mouth Hard palate=bony structure, forms roof of mouth, separates mouth from nasal cavities Soft palate=behind hard palate; separates mouth from nasopharynx Uvula=cone-shaped muscular structure, hangs from middle of soft palate; prevents food from entering nasopharynx during swallowing 1. Mouth Salivary glands=3 pairs (parotid, sublingual, & submandibular); produce saliva Saliva=liquid that lubricates mouth during speech & chewing, moistens food so it can be swallowed Salivary amylase=saliva enzyme (substance that speeds up a chemical reaction) starts the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates (starches) into sugar 2. Pharynx Bolus=chewed food mixed with saliva Pharynx=throat; tube that carries air & food Air goes to trachea; food goes to esophagus When bolus is swallowed, epiglottis covers larynx which stops bolus from entering respiratory tract and makes it go into esophagus 3. -

Digestive System of Goats 3 References

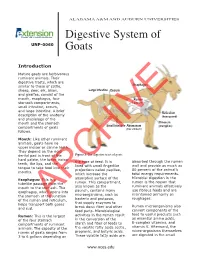

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Digestive System of UNP-0060 Goats Introduction Mature goats are herbivorous ruminant animals. Their digestive tracts, which are similar to those of cattle, Esophagus sheep, deer, elk, bison, Large Intestine Cecum and giraffes, consist of the mouth, esophagus, four Rumen stomach compartments, (paunch) small intestine, cecum, and large intestine. A brief Reticulum description of the anatomy (honeycomb) and physiology of the mouth and the stomach Omasum Small Intestine Abomasum (manyplies) compartments of goats (true stomach) follows. Mouth: Like other ruminant animals, goats have no upper incisor or canine teeth. They depend on the rigid dental pad in front of the Figure 1. The digestive tract of goats. hard palate, the lower incisor the type of feed. It is absorbed through the rumen teeth, the lips, and the lined with small fingerlike wall and provide as much as tongue to take food into their projections called papillae, 80 percent of the animal’s mouths. which increase the total energy requirements. Microbial digestion in the Esophagus: This is a absorptive surface of the rumen is the reason that tubelike passage from the rumen. This compartment, ruminant animals effectively mouth to the stomach. The also known as the use fibrous feeds and are esophagus, which opens into paunch, contains many maintained primarily on the stomach at the junction microorganisms, such as roughages. of the rumen and reticulum, bacteria and protozoa, helps transport bothARCHIVE gases that supply enzymes to Rumen microorganisms also and cud. break down fiber and other feed parts. Microbiological convert components of the feed to useful products such Rumen: This is the largest activities in the rumen result as essential amino acids, of the four stomach in the conversion of the B-complex vitamins, and compartments of ruminant starch and fiber of feeds to vitamin K. -

Axis Scientific Human Digestive System (1/2 Size)

Axis Scientific Human Digestive System (1/2 Size) A-105865 48. Body of Pancreas 27. Transverse Colon 02. Hard Palate 47. Pancreatic Notch 07. Nasopharynx 05. Tooth 01. Lower Lip F. Large Intestine 06. Tongue 21. Jejunum A. Oral Cavity 09. Pharyngeal Tonsil 03. Soft Palate 08. Opening to Auditory Tube 28. E. Small Intestine 04. Uvula 11. Palatine Tonsil Descending Colon 40. Gallbladder 37. Round Ligament of Liver 22. Ileum 38. Quadrate Lobe 44. Proper Hepatic Artery 42. Common Hepatic Duct 45. Hepatic Portal Vein C. Esophagus 15. Fundus of Stomach 30. Rectum 29. Sigmoid Colon 13. Cardia 26. Ascending Colon 39. Caudate Lobe 24. Ileocecal Valve 35. Left Lobe of 16. Body of 34. Falciform Liver Stomach 41. Cystic Duct Ligament 36. Right Lobe of Liver G. Liver 31. Anal Canal 14. Pylorus D. Stomach 33. External 18. Duodenum Anal Sphincter Muscle 17. Pyloric Antrum 46. Head of Pancreas 23. Cecum 51. Accessory Pancreatic Duct 49. Tail of 50. Pancreatic 25. Vermiform 20. Minor Duodenal Papilla H. Pancreas Duct Pancreas Appendix 19. Major Duodenal Papilla 32. Internal Anal Sphincter Muscle 01. Lower Lip 20. Minor Duodenal Papilla 39. Caudate Lobe 02. Hard Palate 21. Jejunum 40. Gallbladder 03. Soft Palate 22. Ileum 41. Cystic Duct 42. Common Hepatic Duct 04. Uvula 23. Cecum 43. Common Bile Duct 05. Tooth 24. Ileocecal Valve 44. Proper Hepatic Artery 06. Tongue 25. Vermiform Appendix 45. Hepatic Portal Vein 07. Nasopharynx 26. Ascending Colon 46. Head of Pancreas 08. Opening to Auditory Tube 27. Transverse Colon 47. Pancreatic Notch 09. Pharyngeal Tonsil 28. -

The Avian Cecum: a Review

Wilson Bull., 107(l), 1995, pp. 93-121 THE AVIAN CECUM: A REVIEW MARY H. CLENCH AND JOHN R. MATHIAS ’ ABSTRACT.-The ceca, intestinal outpocketings of the gut, are described, classified by types, and their occurrence surveyed across the Order Aves. Correlation between cecal size and systematic position is weak except among closely related species. With many exceptions, herbivores and omnivores tend to have large ceca, insectivores and carnivores are variable, and piscivores and graminivores have small ceca. Although important progress has been made in recent years, especially through the use of wild birds under natural (or quasi-natural) conditions rather than studying domestic species in captivity, much remains to be learned about cecal functioning. Research on periodic changes in galliform and anseriform cecal size in response to dietary alterations is discussed. Studies demonstrating cellulose digestion and fermentation in ceca, and their utilization and absorption of water, nitrogenous com- pounds, and other nutrients are reviewed. We also note disease-causing organisms that may be found in ceca. The avian cecum is a multi-purpose organ, with the potential to act in many different ways-and depending on the species involved, its cecal morphology, and ecological conditions, cecal functioning can be efficient and vitally important to a birds’ physiology, especially during periods of stress. Received 14 Feb. 1994, accepted 2 June 1994. The digestive tract of most birds contains a pair of outpocketings that project from the proximal colon at its junction with the small intestine (Fig. 1). These ceca are usually fingerlike in shape, looking much like simple lateral extensions of the intestine, but some are complex in struc- ture. -

The Immune-Enhancing Effects of Dietary Fibres and Prebiotics

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (2002), 87, Suppl. 2, S221–S230 DOI: 10.1079/BJN/2002541 q The Authors 2002 https://www.cambridge.org/core The immune-enhancing effects of dietary fibres and prebiotics P. D. Schley and C. J. Field* Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, T6G 2P5 . IP address: The gastrointestinal tract is subjected to enormous and continual foreign antigenic stimuli from 170.106.40.40 food and microbes. This organ must integrate complex interactions among diet, external patho- gens, and local immunological and non-immunological processes. It is critical that protective immune responses are made to potential pathogens, while hypersensitivity reactions to dietary antigens are minimised. There is increasing evidence that fermentable dietary fibres and the , on newly described prebiotics can modulate various properties of the immune system, including 30 Sep 2021 at 08:21:57 those of the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT). This paper reviews evidence for the immune-enhancing effects of dietary fibres. Changes in the intestinal microflora that occur with the consumption of prebiotic fibres may potentially mediate immune changes via: the direct contact of lactic acid bacteria or bacterial products (cell wall or cytoplasmic components) with immune cells in the intestine; the production of short-chain fatty acids from fibre fermen- tation; or by changes in mucin production. Although further work is needed to better define the changes, mechanisms for immunomodulation, and the ultimate impact on immune health, there , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at is convincing preliminary data to suggest that the consumption of prebiotics can modulate immune parameters in GALT, secondary lymphoid tissues and peripheral circulation. -

Digestive Tract Comparison • the Small Intestine Is a Tube Roughly Twenty Feet Long Deided Into the Duodenum, Jejunum and Ileum

• Small Intestine Human/Dog Digestive system or Simple Monogastric Digestion Digestive Tract Comparison • The small intestine is a tube roughly twenty feet long deided into the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. • The first part of the small intestine is the duodenum, the site of most chemical digestive reactions and is Mouth smoother than the rest of the small intestine • A specialized region of the digestive tract designed to break up large particles of food into • Bile, bicarbonate and pancreatic enzymes are secreted into the duodenum to breakdown nutrients in the smaller, more manageable particles chyme so that they can be readily absorbed. • Saliva is added to moisten food and begin carbohydrate breakdown by amylase in humans. •Bicarbonate from the pancreas neutralizes corrosive stomach acid from 3.5 in the stomach to 8.5 in the • There are four main types of teeth in the human or dog: incisors, canines, premolars and small intestine. molars. •Pancreatic enzymes include lipases, peptidases and amylases. •One reason dog and cat canines are much larger than ours is that they need to be able to rip and •Lipases break down fats. Peptidases break down proteins. Amylases break down carbohydrates. tear through tough raw meat. Humans have evolved to eat easier to chew, cooked meat. • Bile from the liver is stored in the gall bladder and secreted into the duodenum to emulsify fat. • While chewing, food is transformed into what is called a bolus, a food ball, and then forced •The jejunum and ileum are next in the small intestine and are covered in villi, finger-like projections.