Amlaíb Cuarán

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding Neil Oliver, “History of Scotland” BBC2, 2009 “ The many armies, tens of thousands of warriors clashed at the site known as Brunanburh where the Mersey Estuary enters the sea . For decades afterwards it was simply known called the Great Battle. This was the mother of all dark-age bloodbaths and would define the shape of Britain into the modern era. Althouggg,h Athelstan emerged victorious, the resistance of the northern alliance had put an end to his dream of conquering the whole of Britain. This had been a battle for Britain, one of the most important battles in British historyyy and yet today ypp few people have even heard of it. 937 doesn’t quite have the ring of 1066 and yet Brunanburh was about much more than blood and conquest. This was a showdown between two very different ethnic identities – a Norse-Celtic alliance versus Anglo-Saxon. It aimed to settle once and for all whether Britain would be controlled by a single Imperial power or remain several separate kingdoms. A split in perceptions which, like it or not, is still with us today”. Some of the people who’ve been trying to sort it out Nic k Hig ham Pau l Cav ill Mic hae l Woo d John McNeal Dodgson 1928-1990 Plan •Background of Brunanburh • Evidence for Wirral location for the battle • If it did happen in Wirra l, w here is a like ly site for the battle • Consequences of the Battle for Wirral – and Britain Background of Brunanburh “Cherchez la Femme!” Ann Anderson (1964) The Story of Bromborough •TheThe Viking -

1 Clontarf 1014

Clontarf 1014 – a battle of the clans? 1. The contemporary record In its account of the battle of Clontarf the northern AU report that Brian, son of Cennétig, king of Ireland, and Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Tara, led an army to Dublin (Áth Cliath) • all of the Leinsterman (Laigin) were assembled to meet him (Brian), the foreigners of Áth Cliath, and a similar number of foreigners of Lochlainn (Scotland) • a sterling battle was fought between them, the like of which had never been encountered before Then the foreigners and the Leinstermen first broke in defeat and were completely wiped out • there fell on the side of the foreign troop Máel Mórda, king of Leinster, and Domnall, king of the Forthuatha • of the foreigners fell Dubgall, son of Amlaíb (= Óláfr), Sigurd, earl (jarl) of Orkney, and Gilla Ciaráin, heir designate of the foreigners, etc. • Brodar who slew Brian, chief of the Scandinavian fleet, together with 6,000 others was also killed or drowned Of the Irish who fell in the counter-shock were Brian, overking of the Irish of Ireland and of the foreigners [of Limerick and Waterford] and of the Britons [of Wales?], the Augustus of the whole of the north-west of Europe [= Ireland] • his son Murchad and the latter’s son Tairdelbach, Conaing, the heir designate of Mumu, Mothla, king of the Déisi Muman, etc. • the list includes numerous kings of various parts of Munster, plus Domnall, the earl of Marr in Scotland • this list carries conviction when analysed against known details The southern AI report similarly, though more -

Arrest Report - 2019

Arrest Report - 2019 Arrest:19TEW-41-A-AR Date:1/1/2019 Last Name: CORREA First Name:YANELA Age: 18 Address:156 CYPRESS ST City:MANCHESTER State: NH Offense COCAINE, TRAFFICKING IN, 36 GRAMS OR MORE, LESS THAN 100 GRAMS Arrest:19TEW-41-AR Date:1/1/2019 Last Name: MENDOZA First Name:ELVIN Age: 22 Address:9 BYRON AVE City:LAWRENCE State: MA Offense COCAINE, TRAFFICKING IN, 36 GRAMS OR MORE, LESS THAN 100 GRAMS WARRANT - 1818CR003461 - TRAFFICKING IN 100 GRMS HEROIN WARRANT-DOCKET#1818CR006396 - OP MV W/ REVOKED LICENSE Arrest:19TEW-294-AR Date:1/2/2019 Last Name: KING First Name:TAMMY Age: 37 Address:181 LOUDON RD City:CONCORD State: NH Offense ASSAULT W/DANGEROUS WEAPON/ TO WIT CLEANING BOTTLE VANDALIZE PROPERTY c266 §126A DISGUISE TO OBSTRUCT JUSTICE WARRANT -LARCENY OVER 1200.00 266/30/B WARRANT - LARCENY OVER 1200.00 - 266/30/A WARRANT - LARCENY OVER 1200.00 BY SINGLE SCHEME - 266/30/B WARRANT - SHOPLIFTING $250+ BY ASPORTATION - 266/30A/S THREAT TO COMMIT CRIME - ASSAULT & BATTERY Arrest:19TEW-337-AR Date:1/3/2019 Last Name: PUNTONI First Name:CORY Age: 27 Address:10 LOCKE ST City:HAVERHILL State: MA Offense WARRANT- DOCKET#1838CR002437-ORDINANCE VIOLATION Arrest:19TEW-470-AR Date:1/3/2019 Last Name: GUTHRIE First Name:CHRISTOPHER Age: 31 Address:108 CHAPEL ST City:LOWELL State: MA Offense Page 1 of 10 WARRANT DOCKET #1711CR001501 C275 S2 THREATENING TO COMMIT CRIME WARRANT DOCKET #1811CR004055 90-23 LICENSE SUSPENDED Arrest:19TEW-485-AR Date:1/3/2019 Last Name: DYESS First Name:CHRISTOPHER Age: 35 Address:133 SHAWSHEEN ST City:TEWKSBURY -

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2020 doi:10.30845/ijll.v7n3p2 Skaldic Panegyric and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Poem on the Redemption of the Five Boroughs Leading Researcher Inna Matyushina Russian State University for the Humanities Miusskaya Ploshchad korpus 6, Moscow Russia, 125047 Honorary Professor, University of Exeter Queen's Building, The Queen's Drive Streatham Campus, Exeter, EX4 4QJ Summary: The paper attempts to reveal the affinities between skaldic panegyric poetry and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle poem on the ‘Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ included into four manuscripts (Parker, Worcester and both Abingdon) for the year 942. The thirteen lines of the Chronicle poem are laden with toponyms and ethnonyms, prompting scholars to suggest that its main function is mnemonic. However comparison with skaldic drápur points to the communicative aim of the lists of toponyms and ethnonyms, whose function is to mark the restoration of the space defining the historical significance of Edmund’s victory. The Chronicle poem unites the motifs of glory, spatial conquest and protection of land which are also present in Sighvat’s Knútsdrápa (SkP I 660. 9. 1-8), bearing thematic, situational, structural and functional affinity with the former. Like that of Knútsdrápa, the function of the Chronicle poem is to glorify the ruler by formally reconstructing space. The poem, which, unlike most Anglo-Saxon poetry, is centred not on a past but on a contemporary event, is encomium regis, traditional for skaldic poetry. ‘The Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ can be called an Anglo-Saxon equivalent of erfidrápa, directed to posterity and ensuring eternal fame for the ruler who reconstructed the spatial identity of his kingdom. -

Suibne Mac Cináeda from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

11/4/2015 4:33 PM https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suibne_mac_Cináeda Suibne mac Cináeda From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Suibne mac Cináeda (died 1034),[2] also known as Suibne mac Cinaeda,[3] Suibne mac Cinaedh,[4] and Suibhne mac Cináeda,[5][note 1] was an Suibne mac Cináeda eleventh-century ruler of the Gall Gaidheil, a population of mixed King of the Gall Gaidheil Scandinavian and Gaelic ethnicity. There is little known of Suibne, as he is only attested in three sources that record the year of his death. He seems to have ruled in a region where Gall Gaidheil are known to have dwelt: either the Hebrides, the Firth of Clyde region, or somewhere along the south- Suibne's name as it appears on folio 16v of Oxford western coast of Scotland from the firth southwards into Galloway. Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson B 488 (the Annals of Tigernach).[1] Suibne's patronym, meaning "son of Cináed", could be evidence that he was a Died 1034 brother of the reigning Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Scotland, and thus a member of the royal Alpínid dynasty. Suibne's career appears to have Dynasty possibly Alpínid dynasty coincided with an expansion of the Gall Gaidheil along the south-west coast Father possibly Cináed mac Maíl Choluim of what is today Scotland. This extension of power may have partially contributed to the destruction of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, an embattled realm which then faced aggressions from Dublin Vikings, Northumbrians, and Scots as well. The circumstances of Suibne's death are unknown, although one possibility could be that he was caught up in the vicious dynastic-strife endured by the Alpínids. -

Archaeology of Mother Earth Sites and Sanctuaries Through the Ages Rethinking Symbols and Images, Art and Artefacts from History and Prehistory

Archaeology of Mother Earth Sites and Sanctuaries through the Ages Rethinking symbols and images, art and artefacts from history and prehistory Edited by G. Terence Meaden BAR International Series 2389 2012 Published by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com BAR S2389 Archaeology of Mother Earth Sites and Sanctuaries through the Ages: Rethinking symbols and images, art and artefacts from history and prehistory © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012 ISBN 978 1 4073 0981 1 Printed in England by 4edge, Hockley All BAR titles are available from: Hadrian Books Ltd 122 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7BP England www.hadrianbooks.co.uk The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com the neolithic monument of newgrange in ireland: a coSmic womb? Kate Prendergast Oxford University, Department of Continuing Education Abstract: This paper argues that the Neolithic monument of Newgrange, in common with comparable monuments known as passage- graves, functioned to facilitate womb-like ritual experiences and birth-based cosmological beliefs. It explores the evidence for the design, material deposits, astronomy, rock art and associated myth at Newgrange to suggest the myriad ways that birth-based ritual and cosmology are invoked at the site, and it locates this evidence in the context of the transition to agriculture with which such monuments were associated. Key words: Neolithic, Newgrange, monument, womb, womb-like, ritual, astronomy, winter solstice, re-birth, ancestors. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Kinship Report for Roy Einar Christopherson

Kinship Report for Roy Einar Christopherson Kinship of Roy Einar Christopherson Name: Birth Date: Relationship: (Christopherson,Stephanie) First Cousin (Fearghal,King in Ossory Dunghal mac) 31st Great Grandfather (Hjaldursson,Veðra-Grímur) 31st Great Grandfather (Kjarvalsdóttir,Rafarta) 29th Great Grandmother (MacCRUNNMAIL,Faelain) 35th Great Grandfather (MacFAELAIN,Cu Chercca) 34th Great Grandfather Böðvar "breiðavað" 1230 20th Great Grandfather "barnakarl", Ölvir 30 Great Grandfather "barnakarl", Ölvir Abt. 810 AD Unrelated "barnakarl", Ölvir 840 AD 33rd Great Grandfather "bíldur", Önundur Abt. 900 AD Unrelated "eldri", Runólfur Þorsteinsson Abt. 1460 12th Great Grandfather "elsta", Guðrún Aradóttir Abt. 1772 3rd Great Grandmother "elsti", Vigfús Arason 18 May 1839 Twenty-Sixth Cousin 2x Removed "fullspakur", Þorkell Abt. 850 AD 27th Great Grandfather "GRAABARD", Guttorm Abt. 1090 Unrelated "háleygski", Grímur Abt. 860 AD Unrelated "hersir", Gormur Abt. 740 AD Unrelated "hjálmur", Þóroddur Abt. 890 AD 26th Great Grandfather "Hvamm-Sturla", (Þórðarson,Sturla) Fifteenth Cousin 21x Removed In Law "hvassi", Úlfur Abt. 830 AD 29th Great Grandfather "Jernside", King of Uppsala Sweden Björn Abt. 777 AD Unrelated "kjöllari", Ketill 670 AD 32nd Great Grandfather "lági", Steinólfur Abt. 840 AD 31st Great Grandfather "mjóbeinn", Þrándur Abt. 850 AD 28th Great Grandfather "mjóvi", Atli 820 AD 31st Great Grandfather "mjóvi", Oddur Abt. 910 AD 29th Great Grandparent "rauði", Sighvatur Abt. 845 AD Unrelated "reyðarsíða", Þorgils Abt. 780 AD 32nd Great -

List of Manuscript and Printed Sources Current Marks and Abreviations

1 1 LIST OF MANUSCRIPT AND PRINTED SOURCES CURRENT MARKS AND ABREVIATIONS * * surrounds insertions by me * * variant forms of the lemmata for finding ** (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted by me + + surrounds insertion from the addenda ++ (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted from addenda † † marks what is (I believe) certainly wrong !? marks an unidentified source reference [ro] Hogan’s Ro [=reference omitted] {1} etc. different places but within a single entry are thus marked Identical lemmata are numbered. This is merely to separate the lemmata for reference and cross- reference. It does not imply that the lemmata always refer to separate names SOURCES Unidentified sources are listed here and marked in the text (!?). Most are not important but they are nuisance. Identifications please. 23 N 10 Dublin, RIA, 967 olim 23 N 10, antea Betham, 145; vellum and paper; s. xvi (AD 1575); see now R. I. Best (ed), MS. 23 N 10 (formerly Betham 145) in the Library of the RIA, Facsimiles in Collotype of Irish Manuscript, 6 (Dublin 1954) 23 P 3 Dublin, RIA, 1242 olim 23 P 3; s. xv [little excerption] AASS Acta Sanctorum … a Sociis Bollandianis (Antwerp, Paris, & Brussels, 1643—) [Onomasticon volume numbers belong uniquely to the binding of the Jesuits’ copy of AASS in their house in Leeson St, Dublin, and do not appear in the series]; see introduction Ac. unidentified source Acallam (ed. Stokes) Whitley Stokes (ed. & tr.), Acallam na senórach, in Whitley Stokes & Ernst Windisch (ed), Irische Texte, 4th ser., 1 (Leipzig, 1900) [index]; see also Standish H. -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

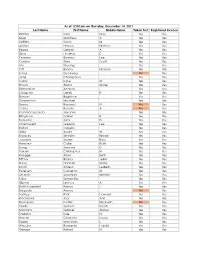

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes