Sergeant Harold Lyon, East Riding Yeomanry – Lantern Slide Lecture Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yorkshire Wolds Way Accommodation and Information Guide

Accommodation and Information Guide 79 miles of peaceful walking on the beautiful Yorkshire Wolds Yorkshire Wolds Way Accommodation & Information Guide 2 Contents Welcome . 3 Key . 6 West Heslerton . 17 East Heslerton . 18 About the Accommodation Guide . 3 Symbols for Settlements . 6 Sherburn . 18 Maps and Guides . 3 Symbols for Accommodation . 6 Weaverthorpe . 18 Public Transport . 3 Accommodation Symbols . 6 Ganton . 18 Hessle . 7 European Visitors . 3 Willerby Brow . 19 North Ferriby . 8 Out for the Day? . 3 Langtoft . 19 Welton . 8 Staxton . .. 19 Brough . 9 Holiday Operators . 4 Wold Newton . 19 Elloughton . 9 Book My Trail . 4 Flixton . 19/20 Brantingham . 9 Hunmanby . 20 Brigantes . 4 South Cave . 10 Muston . 20 Footpath Holidays . 4 North Newbald . 11 Filey . 21 Contours Walking Holidays . 4 Sancton . 11 Discovery Travel . .. 4 Goodmanham . 11 Mileage Chart . 23 Market Weighton . 12 Mickledore . 4 Shiptonthorpe . 12/13 Baggage Services . 4 Londesborough . 13 Nunburnholme . 13 Brigantes . 4 Pocklington . 13 Trail Magic Baggage . 4 Kilnwick Percy . 14 Wander – Art along the Yorkshire Wolds Way . 5 Millington . 14 Yorkshire Wolds Way Official Completion Book . 5 Meltonby . 15 Get a Certificate . .. 5 Huggate . 15 Fridaythorpe . 16 Buy mugs, badges, even Fingerblades! . 5 Thixendale . 16 Try a pint of Wolds Way Ale! . 5 Wharram le Street . .. 16 Did You Enjoy Yourself? . 5 North Grimston . .. 16 Comments . 5 Rillington . 17 Note: this contents page is interactive . Further information . 5 Wintringham . 17 Click on a title to jump to that section . This edition published April 2021 Yorkshire Wolds Way Accommodation & Information Guide 3 Welcome to the Yorkshire Wolds Way Accommodation and Information Guide This guide has been prepared to give you all Public Transport Flixton Muston Willerby Brow those extra details that you need in order to If you are planning to walk the full route from Hessle to Filey then it is Ganton Flixton Wold FILEY better to leave the car at home and travel by Public Transport . -

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County Postcode 64 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 70 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 72 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 74 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 80 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 82 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 84 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 1 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 2 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 3 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 4 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 1 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 3 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 5 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 7 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 9 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 11 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 13 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 15 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 17 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 19 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 21 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 23 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 25 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 -

Pocklington School Bus Routes

OUR School and other private services MALTON RILLINGTON ROUTES Public services Revised Sept 2020 NORTON BURYTHORPE DRIFFIELD LEPPINGTON NORTH SKIRPENBECK WARTHILL DALTON GATE STAMFORD HELMSLEY BRIDGE WARTER FULL MIDDLETON NEWTON SUTTON ON THE WOLDS N ELVINGTON UPON DERWENT YORK KILNWICK SUTTON POCKLINGTON UPON DERWENT AUGHTON LUND COACHES LECONFIELD & MINIBUSES BUBWITH From York York B & Q MOLESCROFT WRESSLE MARKET Warthill WEIGHTON SANCTON Gate Helmsley BISHOP BEVERLEY Stamford Bridge BURTON HOLME ON NORTH Skirpenbeck SPALDING MOOR NEWBALD Full Sutton HEMINGBOROUGH WALKINGTON Pocklington SPALDINGTON SWANLAND From Hull NORTH CAVE North Ferriby Swanland Walkington HOWDEN SOUTH NORTH HULL Bishop Burton CAVE FERRIBY Pocklington From Rillington Malton RIVER HUMBER Norton Burythorpe HUMBER BRIDGE Pocklington EAST YORKSHIRE BUS COMPANY Enterprise Coach Services (am only) PUBLIC TRANSPORT South Cave Driffield North Cave Middleton-on-the-Wolds Hotham North Newbald 45/45A Sancton Hemingbrough Driffield Babthorpe Market Weighton North Dalton Pocklington Wressle Pocklington Breighton Please contact Tim Mills Bubwith T: 01430 410937 Aughton M: 07885 118477 Pocklington X46/X47 Hull Molescroft Beverley Leconfield Bishop Burton Baldry’s Coaches Kilnwick Market Weighton BP Garage, Howden Bus route information is Lund Shiptonthorpe Water Tower, provided for general guidance. Pocklington Pocklington Spaldington Road End, Routes are reviewed annually Holme on Spalding Moor and may change from year to Pocklington (am only) For information regarding year in line with demand. Elvington any of the above local Please contact Parents are advised to contact Sutton-on-Derwent service buses, please contact Mr Phill Baldry the Transport Manager, or the Newton-on-Derwent East Yorkshire Bus M:07815 284485 provider listed, for up-to-date Company Email: information, on routes, places Please contact the Transport 01482 222222 [email protected] and prices. -

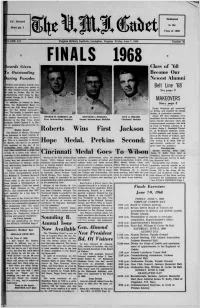

FINALS Livards Given Class of '68 'O Outstanding Become Our Hiring Parades Newest Alumni

Dedicated G.C. Revised to tlie Story pg. 3 Class of 1968 •LUME LIV Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia. Friday, June 7, 1968 Number 30 X FINALS livards Given Class of '68 'o Outstanding Become Our hiring Parades Newest Alumni pi pliliiitiary and athletic awards were Resented to twenty-one cadets at Belt Line '68 Ae ftrst awards review parade of See page 3 "le year on Friday, May 24. The •esenitations were made by Miaj eneral George R. E. Shell, VMI iUperinitendent. MAKEOVERS y In addition ito honors in these Story page 2 elds, the Regimental Band re- eived the VMI Blood Donor Tro K Finals Weekend got underway >by for the fourth consecutivr on Friday and reached its climax 'ear. The trophy is awarded annu- Sunday at graduation exercises. •liy to the oadet company having' About 217 first classmen were GEORGE H. ROBERTS, JR. KENNETH J. PERKINS, GUY A. WILSON he highest percentage of contri- candidates for the baccalaureate de- First Jackson-Hope Medalist , Second Jackson-Hope Medalist Cincinnati Medalist •utionis to the Red Cross blood grees Sunday afternoon when the >rogram. Cadet Captain T. B. Bar- commencement ceremony was held on Jr. accepted the award for his in front of Preston Library at 2 company. o'clock. Judge J. Randolph Tucker Martin Award Roberts Wins First Jackson Jr. of Richmond Hustings Court, Th« Charles R. Martin. '55 award a VMI graduate and former presi- was presented to cadet Captain W dent of the Board of Visitors, gave P. Cobb, Echo company commiandi. the commencement address. Maj. er. -

Sancton Parish Council Parish Council

Sancton Parish Council Minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on Monday 15th July 2019 at 7.00pm in Sancton Methodist Chapel, Rispin Hill, Sancton _________________________________________________________________________________ Present Cllr Derek Cary (Chairman) Cllr Anita Liley Cllr Chris Shepherd Cllr Pat Parvin Cllr Sally Wightman Cllr Marilyn Wintersgill Ward Cllr Mike Stathers 1 Member of the Public 150719/1 Apologies None. 150719/2 Declarations of Interest a) No declarations of interest by any member of the council in respect of the agenda items. b) No dispensations given to any member of the council in respect of the agenda items. 150719/3 Minutes of Previous Meeting The minutes of the meeting held on the 17 th June 2019 were approved by members and signed by the Chairman. Proposed: Cllr Wightman, seconded: Cllr Parvin. 150719/4 Public Participation Mr R Thomson provided an update on his work towards an interpretation board for the village which will focus on its history. It is proposed to use Jenko Ltd for the project as they have previously been involved in the village design statement, village hall and other endeavours. Themes explored across the two boards will include a reproduced Home Guard map, the Saxon burial ground, Houghton Hall and Sancton during both World Wars. It is estimated that the cost of the project will be £300-400 maximum. It will also be fitting to coincide its completion with the VE75 commemorations next year. 150719/5 Reports from Ward Councillor(s) Ward Cllr Stathers updated the Parish Council on activities within East Riding of Yorkshire Council: • Low Street parking problems – Response from ERYC: ‘the council has a waiting restriction policy for the introduction of parking restrictions and one of the elements, along with the need to satisfy traffic management objectives, is that they will not normally be considered in rural villages or urban residential areas unless justified by a poor accident record or the obstruction of bus services. -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

East Yorkshire Hull

East Yorkshire Hull - York X46 via Beverley - Market Weighton - Pocklington Hull - York X47 via Cottingham - Beverley - Market Weighton - Pocklington Monday to Friday Ref.No.: COB Service No X47 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 X46 Hull Interchange --- 0615 0635 0720 0830 0930 1030 1130 1230 1330 1430 1530 1630 1730 1810 1905 Beverley Road (Haworth Arms) --- 0623 0643 0729 0841 0941 1041 1141 1241 1341 1441 1541 1641 1741 1821 1913 Beverley Road (Tesco) --- 0629 0649 0735 0847 0947 1047 1147 1247 1347 1447 1547 1647 1747 1827 1919 Beverley (Normandy Avenue) --- 0638 0658 0745 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1557 1657 1757 1837 1928 Beverley Bus Station Arr --- 0644 0704 0751 0905 1005 1105 1205 1305 1405 1505 1605 1705 1805 1845 1934 Beverley Bus Station Dep --- 0647 0707 0757 0907 1007 1107 1207 1307 1407 1507 1612 1717 1817 --- 1937 Bishop Burton (Altisidora) --- 0655 0715 0805 0915 1015 1115 1215 1315 1415 1515 1620 1725 1825 --- 1945 Market Weighton Sancton Road --- 0707 0727 0817 0927 1027 1127 1227 1327 1427 1527 1632 1737 1837 --- 1957 Market Weighton (Griffin) Arr --- 0709 0729 0819 0929 1029 1129 1229 1329 1429 1529 1634 1739 1839 --- 1959 Market Weighton (Griffin) Dep --- 0710 0730 0822 0932 1032 1132 1232 1332 1432 1532 1637 1742 1842 --- 1959 Shiptonthorpe (Crown) --- 0717 0737 0829 0937 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1537 1642 1747 1847 --- 2004 Hayton (Green) --- 0720 0740 0832 0940 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1540 1645 1750 1850 --- 2007 Pocklington EY Depot Arr --- 0725 0745 0837 0945 1045 1145 1245 1345 -

Download Download

British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2021 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 19 March 2021 Citation: Roslyn Shepherd King Pike, ‘What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918’, British Journal for Military History, 7.1 (2021), pp. 87-112. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of IDENTIFYING MILITARY ENGAGEMENTS IN EGYPT & THE LEVANT 1915-1918 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915- 1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike* Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the official names listed in the 'Egypt and Palestine' section of the 1922 report by the British Army’s Battles Nomenclature Committee and compares them with descriptions of military engagements in the Official History to establish if they clearly identify the events. The Committee’s application of their own definitions and guidelines during the process of naming these conflicts is evaluated together with examples of more recent usages in selected secondary sources. The articles concludes that the Committee’s failure to accurately identify the events of this campaign have had a negative impacted on subsequent historiography. Introduction While the perennial rose would still smell the same if called a lily, any discussion of military engagements relies on accurate and generally agreed on enduring names, so historians, veterans, and the wider community, can talk with some degree of confidence about particular events, and they can be meaningfully written into history. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

Interview Transcript As

Australians at War Film Archive Robert Douglas (Bob) - Transcript of interview Date of interview: 8th March 2004 http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/1609 Tape 1 00:36 Rolling now. OK Bob, I’ll just ask you to explain to us in ten minutes, what’s happened in your life. Well I suppose if you want to know what’s happened in my life, I would like to go back to really the very, early the beginning which involves my parents. And to understand my life perhaps, an understanding of my 01:00 parents would be useful. I’ll start with my mother, who was a magnificent woman. And she was born in London in 1878. And she was born, as she used to tell me, in the sound of Bow Bells, which made her a Cockney, really, from the Soho area. 01:30 She told me stories of, in her childhood, listening to the bell toll 80 times for each year of Queen Victoria’s life, and so it went on. Her family did tailoring for London tailors, Saville Row tailors. My maternal grandmother, whom 02:00 I don’t think I ever met, I may have done when I was very young, she made hand-pearled gentlemen’s jackets and waistcoats, that is invisible stitching, and that’s how they made their living. My mother found employment in a London hotel as a housemaid, and she was evidently very good at that. And she 02:30 progressed and became Housekeeper of a major hotel, which was a very important position in the hotel running. -

EAST RIDING Yorl{SHIRE. KILNWICK

E:ILNWICK·ON-THE·} 666 { I W.QLDS. EAST RIDING YORl{SHIRE. KILNWICK. Hesp John, blacksmith Pickering Miles, farmer, Glebe farn1 DuCane Lady, Kilnwick hall J ackson Isaao, farmer, New farm Pinder Jn. market gardnr. & carrier Jackson James R. grocer & carrier Robson John, farmer, Home farm COHMKRCIAL. J enkinson J ames, shoe maker Sisson William, joiner & wheelwrigm .Anderson Joseph, farmer, Lodge frm Newlove John Robert, farmer, Foun- Ward Andrew, carrier Bentley Jas. frmr.Kilnwick common tain house Bentley Thos. tailor, Kilnwick lodges Newlove William, farmer & cattle BRACKEN. Olappison Tom Ha.rry, frmr.Carr frm dealer, Town farm Staveley Frederick Simpson, farmer Davis Thos. farmer, J,nnd Moor farm Oldroyd Fredk.frmr.Lit.Fountain frm Wardell George, farm bailiff to Duggleby Chas.Hy.frmr.HornHill top Osborne Charles, carrier, market Frederi.ek S. Staveley e~q. (postal gardener & assistant overseer address, Cranswick) XILNWICK PERCY is a parish, township and small residence, in the gift of the Archbishop of York, and village 1~ miles north-east frWl Pocklington station on held since 1903 by the Rev. Waiter Ernest Bot..ty M.A.. of · the York and Market Weighton section of the North Selwyn College, Cambridge, who is also vicar of and Eastern railway, 14! south-east from York and 27! !1-om resides at Warter. Tithe amounting to £x5o is appro. Hull, in the Howdenshire division of the Biding, Wilton priated to the deanery of York. Kilnwick Percy Hall Beacon division of the wapentake of Barthill, Wilton is a beautiful mansion of stone surmunded with pleasure Eea'OOil petty -sessional dll.vision, Pocklington union and grounds, including a spacious lawn and a fine lake, county court district, II"Ural deanery of Pocklington, arch- and is the seat of Basil Duncombe esq.