Inquiry Into Homelessness in Victoria Final Report: Summary Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book 1 Tuesday, 23 December 2014

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 1 Tuesday, 23 December 2014 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier ......................................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education ............................. The Hon. J. A. Merlino, MP Treasurer ....................................................... The Hon. T. H. Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Employment ............ The Hon. J. Allan, MP Minister for Industry and Minister for Energy and Resources ........... The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Roads and Road Safety and Minister for Ports ............. The Hon. L. A. Donnellan, MP Minister for Tourism and Major Events, Minister for Sport and Minister for Veterans .................................................. The Hon. J. H. Eren, MP Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ........... The Hon. M. P. Foley, MP Minister for Emergency Services and Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation .................................. The Hon. J. F. Garrett, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services .............. The Hon. J. Hennessy, MP Minister for Training and Skills .................................... The Hon. S. R. Herbert, MLC Minister for Local Government, Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Minister for Industrial Relations ................................. The Hon. N. M. Hutchins, MP Special Minister of State .......................................... The Hon. G. Jennings, MLC Minister for Families and Children, and Minister for Youth Affairs ...... The Hon. J. Mikakos, MLC Minister for Environment, Climate Change and Water ................. The Hon. L. -

Liberal Nationals Released a Plan

COVID-19 RESPONSE May 2020 michaelobrien.com.au COVID-19 RESPONSE Dear fellow Victorians, By working with the State and Federal Governments, we have all achieved an extraordinary outcome in supressing COVID-19 that makes Victoria – and Australia - the envy of the world. We appreciate everyone who has contributed to this achievement, especially our essential workers. You have our sincere thanks. This achievement, however, has come at a significant cost to our local economy, our community and to our way of life. With COVID-19 now apparently under a measure of control, it is urgent that the Andrews Labor Government puts in place a clear plan that enables us to take back our Michael O’Brien MP lives and rebuild our local communities. Liberal Leader Many hard lessons have been learnt from the virus outbreak; we now need to take action to deal with these shortcomings, such as our relative lack of local manufacturing capacity. The Liberals and Nationals have worked constructively during the virus pandemic to provide positive suggestions, and to hold the Andrews Government to account for its actions. In that same constructive manner we have prepared this Plan: our positive suggestions about what we believe should be the key priorities for the Government in the recovery phase. This is not a plan for the next election; Victorians can’t afford to wait that long. This is our Plan for immediate action by the Andrews Labor Government so that Victoria can rebuild from the damage done by COVID-19 to our jobs, our communities and our lives. These suggestions are necessarily bold and ambitious, because we don’t believe that business as usual is going to be enough to secure our recovery. -

2010 Victorian State Election Summary of Results

2010 VICTORIAN STATE ELECTION 27 November 2010 SUMMARY OF RESULTS Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Results.......................................................................................... 3 Detailed Results by District ............................................................................... 8 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Result ........................................................ 24 Regional Summaries....................................................................................... 30 By-elections and Casual Vacancies ................................................................ 34 Legislative Council Results Summary of Results........................................................................................ 35 Incidence of Ticket Voting ............................................................................... 38 Eastern Metropolitan Region .......................................................................... 39 Eastern Victoria Region.................................................................................. 42 Northern Metropolitan Region ........................................................................ 44 Northern Victoria Region ................................................................................ 48 South Eastern Metropolitan Region ............................................................... 51 Southern Metropolitan Region ....................................................................... -

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Labor

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Branch Victorian Labor MPs We want you to email the MP in the electoral district where your school is based. If your school is not in a Labor held area then please email a Victorian Labor upper house MP who covers your area from the separate list below. Click here if you need to look it up. Email your local MP and cc the Education Minister and the Premier Legislative Assembly MPs (lower house) ELECTORAL DISTRICT MP NAME MP EMAIL MP TELEPHONE Albert Park Martin Foley [email protected] (03) 9646 7173 Altona Jill Hennessy [email protected] (03) 9395 0221 Bass Jordan Crugname [email protected] (03) 5672 4755 Bayswater Jackson Taylor [email protected] (03) 9738 0577 Bellarine Lisa Neville [email protected] (03) 5250 1987 Bendigo East Jacinta Allan [email protected] (03) 5443 2144 Bendigo West Maree Edwards [email protected] 03 5410 2444 Bentleigh Nick Staikos [email protected] (03) 9579 7222 Box Hill Paul Hamer [email protected] (03) 9898 6606 Broadmeadows Frank McGuire [email protected] (03) 9300 3851 Bundoora Colin Brooks [email protected] (03) 9467 5657 Buninyong Michaela Settle [email protected] (03) 5331 7722 Activate. Educate. Unite. 1 Burwood Will Fowles [email protected] (03) 9809 1857 Carrum Sonya Kilkenny [email protected] (03) 9773 2727 Clarinda Meng -

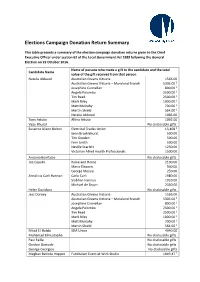

Elections Campaign Donation Return Summary

Elections Campaign Donation Return Summary This table presents a summary of the election campaign donation returns given to the Chief Executive Officer under section 62 of the Local Government Act 1989 following the General Election on 22 October 2016. Name of persons who made a gift to the candidate and the total Candidate Name value of the gift received from that person Natalie Abboud Australian Greens Victoria 1566.00 Australian Greens Victoria – Moreland Branch 5305.00 5 Josephine Connellan 800.00 1 Angela Palombo 2500.00 1 Tim Read 2500.00 1 Mark Riley 1000.00 1 Matt Mulcahy 700.00 1 Martin Shield 564.00 1 Natalie Abboud 1085.00 Tony Astuto Alfina Astuto 1092.00 Vijay Bhusal No disclosable gifts Susanne Alison Bolton Electrical Trades Union 13,408 2 Sean Brocklehurst 500.00 Tim Gooden 500.00 Fern Smith 500.00 Neville Scarlett 1250.00 Victorian Allied Health Professionals 1500.00 Antonio Bonifazio No disclosable gifts Joe Caputo Raine and Horne 2100.00 Mario Elezovic 500.00 George Messie 250.00 Annalivia Carli Hannan Carlo Carli 1980.00 Siobhan Hannan 1910.00 Michael de Bruyn 2350.00 Helen Davidson No disclosable gifts Jess Dorney Australian Greens Victoria 1566.00 Australian Greens Victoria – Moreland Branch 5305.00 5 Josephine Connellan 800.00 1 Angela Palombo 2500.00 1 Tim Read 2500.00 1 Mark Riley 1000.00 1 Matt Mulcahy 700.00 1 Martin Shield 564.00 1 Milad El‐Halabi SDA Union 4040.00 Mohamad Elmustapha No disclosable gifts Paul Failla No disclosable gifts Gordon Gartside No disclosable gifts George Georgiou No disclosable gifts -

Inquiry Into the Impact of the COVID‑19 Pandemic on the Tourism and Events Sectors

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Economy and Infrastructure Committee Inquiry into the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the tourism and events sectors Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2021 PP No 254, Session 2018–2021 ISBN 978 1 922425 35 5 (print version), 978 1 922425 36 2 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Mr Enver Erdogan Mr Bernie Finn Mr Rodney Barton Southern Metropolitan Western Metropolitan Eastern Metropolitan Mr Mark Gepp Mrs Bev McArthur Mr Tim Quilty Mr Lee Tarlamis OAM Northern Victoria Western Victoria Northern Victoria South Eastern Metropolitan Participating members Dr Matthew Bach, Eastern Metropolitan Ms Melina Bath, Eastern Victoria Dr Catherine Cumming, Western Metropolitan Hon David Davis, Southern Metropolitan—substitute Member for Mrs McArthur for this Inquiry Mr David Limbrick, South Eastern Metropolitan Hon Wendy Lovell, Northern Victoria—substitute Member for Mr Finn for this Inquiry Mr Andy Meddick, Western Victoria Mr Craig Ondarchie, Northern Metropolitan Hon Gordon Rich-Phillips, South Eastern Metropolitan Ms Sheena Watt, Northern Metropolitan ii Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee About the Committee Functions The Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee’s functions are to inquire into and report on any proposal, matter or thing concerned with agriculture, commerce, infrastructure, industry, major projects, public sector finances, transport and education. As a Standing Committee, it may inquire into, hold public hearings, consider and report on any Bills or draft Bills, annual reports, estimates of expenditure or other documents laid before the Legislative Council in accordance with an Act, provided these are relevant to its functions. -

Victoria New South Wales

Victoria Legislative Assembly – January Birthdays: - Ann Barker - Oakleigh - Colin Brooks – Bundoora - Judith Graley – Narre Warren South - Hon. Rob Hulls – Niddrie - Sharon Knight – Ballarat West - Tim McCurdy – Murray Vale - Elizabeth Miller – Bentleigh - Tim Pallas – Tarneit - Hon Bronwyn Pike – Melbourne - Robin Scott – Preston - Hon. Peter Walsh – Swan Hill Legislative Council - January Birthdays: - Candy Broad – Sunbury - Jenny Mikakos – Reservoir - Brian Lennox - Doncaster - Hon. Martin Pakula – Yarraville - Gayle Tierney – Geelong New South Wales Legislative Assembly: January Birthdays: - Hon. Carmel Tebbutt – Marrickville - Bruce Notley Smith – Coogee - Christopher Gulaptis – Terrigal - Hon. Andrew Stoner - Oxley Legislative Council: January Birthdays: - Hon. George Ajaka – Parliamentary Secretary - Charlie Lynn – Parliamentary Secretary - Hon. Gregory Pearce – Minister for Finance and Services and Minister for Illawarra South Australia Legislative Assembly January Birthdays: - Duncan McFetridge – Morphett - Hon. Mike Rann – Ramsay - Mary Thompson – Reynell - Hon. Carmel Zollo South Australian Legislative Council: No South Australian members have listed their birthdays on their website Federal January Birthdays: - Chris Bowen - McMahon, NSW - Hon. Bruce Bilson – Dunkley, VIC - Anna Burke – Chisholm, VIC - Joel Fitzgibbon – Hunter, NSW - Paul Fletcher – Bradfield , NSW - Natasha Griggs – Solomon, ACT - Graham Perrett - Moreton, QLD - Bernie Ripoll - Oxley, QLD - Daniel Tehan - Wannon, VIC - Maria Vamvakinou - Calwell, VIC - Sen. -

Federal & State Mp Phone Numbers

FEDERAL & STATE MP PHONE NUMBERS Contact your federal and state members of parliament and ask them if they are committed to 2 years of preschool education for every child. Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Aston Alan Tudge Liberal (03) 9887 3890 Hotham Clare O’Neil Labor (03) 9545 6211 Ballarat Catherine King Labor (03) 5338 8123 Indi Catherine McGowan Independent (03) 5721 7077 Batman Ged Kearney Labor (03) 9416 8690 Isaacs Mark Dreyfus Labor (03) 9580 4651 Bendigo Lisa Chesters Labor (03) 5443 9055 Jagajaga Jennifer Macklin Labor (03) 9459 1411 Bruce Julian Hill Labor (03) 9547 1444 Kooyong Joshua Frydenberg Liberal (03) 9882 3677 Calwell Maria Vamvakinou Labor (03) 9367 5216 La Trobe Jason Wood Liberal (03) 9768 9164 Casey Anthony Smith Liberal (03) 9727 0799 Lalor Joanne Ryan Labor (03) 9742 5800 Chisholm Julia Banks Liberal (03) 9808 3188 Mallee Andrew Broad National 1300 131 620 Corangamite Sarah Henderson Liberal (03) 5243 1444 Maribyrnong William Shorten Labor (03) 9326 1300 Corio Richard Marles Labor (03) 5221 3033 McEwen Robert Mitchell Labor (03) 9333 0440 Deakin Michael Sukkar Liberal (03) 9874 1711 McMillan Russell Broadbent Liberal (03) 5623 2064 Dunkley Christopher Crewther Liberal (03) 9781 2333 Melbourne Adam Bandt Greens (03) 9417 0759 Flinders Gregory Hunt Liberal (03) 5979 3188 Melbourne Ports Michael Danby Labor (03) 9534 8126 Gellibrand Timothy Watts Labor (03) 9687 7661 Menzies Kevin Andrews Liberal (03) 9848 9900 Gippsland Darren Chester National -

Inquiry Into the Impact of Animal Rights Activism on Victorian Agriculture

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Economy and Infrastructure Committee Inquiry into the impact of animal rights activism on Victorian agriculture Parliament of Victoria Economy and Infrastructure Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2020 PP No 112, Session 2018-20 ISBN 978 1 925703 94 8 (print version), 978 1 925703 95 5 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Nazih Elasmar Bernie Finn Rodney Barton Northern Metropolitan Westerm Metropolitan Eastern Metropolitan Mark Gepp Bev McArthur Tim Quilty Sonja Terpstra Northern Victoria Western Victoria Northern Victoria Eastern Metropolitan Participating members Melina Bath, Eastern Victoria Dr Catherine Cumming, Western Metropolitan Hon. David Davis, Southern Metropolitan David Limbrick, South Eastern Metropolitan Andy Meddick, Western Victoria Craig Ondarchie, Northern Metropolitan Hon. Gordon Rich-Phillips, South Eastern Metropolitan Hon. Mary Wooldridge, Eastern Metropolitan ii Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee About the committee Functions The Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee’s functions are to inquire into and report on any proposal, matter or thing concerned with agriculture, commerce, infrastructure, industry, major projects, public sector finances, transport and education. As a Standing Committee, it may inquire into, hold public hearings, consider and report on any Bills or draft Bills, annual reports, estimates of expenditure or other documents laid before the Legislative Council in accordance with an Act, provided these are relevant to its functions. Secretariat Patrick O’Brien, Committee Manager Kieran Crowe, Inquiry Officer Caitlin Connally, Research Assistant Justine Donohue, Administrative Officer Contact details Address Legislative Council Economy and Infrastructure Committee Parliament of Victoria Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 8682 2869 Email [email protected] Web https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/eic-lc This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

The 2010 Victorian State Election

Research Service, Parliamentary Library, Department of Parliamentary Services Research Paper The 2010 Victorian State Election Bella Lesman, Rachel Macreadie and Greg Gardiner No. 1, April 2011 An analysis of the Victorian state election which took place on 27 November 2010. This paper provides an overview of the election campaign, major policies, opinion polls data, the outcome of the election in both houses, and voter turnout. It also includes voting figures for each Assembly District and Council Region. This research paper is part of a series of papers produced by the Library’s Research Service. Research Papers are intended to provide in-depth coverage and detailed analysis of topics of interest to Members of Parliament. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. P a r l i a m e n t o f V i c t o r i a ISSN 1836-7941 (Print) 1836-795X (Online) © 2011 Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of Parliamentary Services, other than by Members of the Victorian Parliament in the course of their official duties. Parliamentary Library Research Service Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 PART A: THE CAMPAIGN......................................................................................... 3 1. The Campaign: Key Issues, Policies and Strategies ......................................... 3 1.1 The Leaders’ Debates....................................................................................... 6 1.2 Campaign Controversies................................................................................... 7 1.3 Preference Decisions and Deals...................................................................... -

Electoral Regulation Research Network Newsletter October 2017

Electoral Regulation Research Network Newsletter E RRN Electoral Regulation Research Network October 2017 MELBOURNE LAW SCHOOL Dual Citizenship Cases: In the matter of questions referred to the Court of Disputed Returns pursuant to section 376 of the Commonwealth Electoral Director’s Message Act 1918 (Cth) concerning: Matthew Canavan, Scott Ludlam, Larissa Waters, 2 Malcolm Roberts, Barnaby Joyce, Fiona Nash, Nick Xenophon 3 Electoral News Re Roberts [2017] HCA 39 Alley v Gillespie 12 Research Collaboration Initiative Brooks v Easther (No 3) [2017] TASSC 54 Forthcoming Events 14 Hussain v ACT Electoral Commission 16 Event Reports Moonee Valley City Council Myrnong Ward election. Victorian Electoral Commission v Municipal Electoral Tribunal (Review and Regulation) [2017] VCAT 1156 22 Working Papers Manningham City Council Koonung Ward election: Victorian Electoral 22 Recent Publications Commission v Municipal Electoral Tribunal Z485/2017 24 Case Notes Robert Arthur Smith – Fail to lodge a declaration for a political party Director’s Message I am delighted to say that the New South Wales Electoral Commission, Victorian Electoral Commission and Melbourne Law School have committed to funding the Electoral Regulation Research Network for another three years (2018-2021). This milestone is the result of the efforts of many, in particular, the Network’s convenors and editors; its Administrator; and its Governance Board. At this juncture, it may be useful to be reminded of the rationale of the Network. An essential starting point is, of course, its founding document which provides that ‘(t)he purpose of the Network is to foster exchange and discussion amongst academics, electoral commissions and other interested groups on research relating to electoral regulation’. -

Advocacy Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL ADVOCACY REPORT 2019/20 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Wyndham City has a diverse and friendly During this term of Council, Wyndham City community, a relaxing lifestyle and endless has yielded significantly positive results for the business opportunities. It is the link between community. Some of the key achievements Melbourne and Geelong, Victoria’s two largest include: cities, making it an area of great economic • Significant levels of investment from the significance that extends beyond its own region, State and Federal Government towards impacting the rest of the state. infrastructure projects including level crossing Wyndham City is one of Australia’s fastest removals, new and updated train station car growing municipalities, with our population parks, and major road upgrades. expected to surpass 500,000 by 2040. A • Working with the private sector in the rapid population growth has created new planning and construction of major opportunities for the 270,000 people who infrastructure projects, including the Western already call Wyndham home. United Football Club’s Wyndham City As a community, we have always supported Stadium. one another in times of need. During this • State Government funding for new and coronavirus pandemic, there has been locally- upgraded primary and secondary schools. led initiatives aimed at supporting vulnerable members of our community, including the • Implementation of social and employment supply of food parcels and vouchers, and our programs that assist members of the Check in and Chat services. Council has also community who have experienced difficulty been responding rapidly to the social and in finding employment or opportunities to economic shock brought on by this pandemic upskill.