A Critique of Robert S. Hartman's 'Four Axiological Proofs of the Infinite Aluev of Man'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

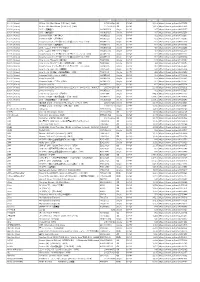

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

PAINTER. Work, As the Deiail Was Car- Hibah Lodob, Nols.F

"3T 35X 13 'WPAtssr SAyB-aaiyjsaS- ' 4 VOLUME 1. NEWTOWN, CO'., JAN. 31, W7M. JOHN T. PEARCE, Editor and Manager. Subscription Price, $1.00 A Year PHOFESSIONAL CARDS. There the chase stopped. If I pur. Before leaving the depot I examined A , Trap for Brigands. sued the object much further I was left my Doles. "On the 21t of January Za- WM. O. WILK, M. O., uualdbd to grope la the dark. none, alone, bad engaged apartments in HOW A BAND WAS WIPED OUT. the Rue Physician and Surgeon, Bandy Hook, Ot. Had It not been for one fact I should Racpart. His landlord said be nn.IIHBD ITMI TH0BS0AT. The Vsrdarelll band, so called from have abandoned, In Ihe press of oilier seldom went out saw no company.'' AT FAIRFIELD U. R. LIVE TOO LONG. their cbeif and bis brothers, had for NEWTOWN, COUNTY, CONN. N.BETTS, JR, . TO business, the matter at once. That one I was dumbfounded. The woman, more two committed A. A. Stmeel, - and D It la aad to lie down In the cold, cold grave. than years great Fut'r Vrop'r. fact, which told Die In the imperative then.dropped from the drama Hint night. ditor and DENTIST, When the mind is strong, and the hoart la brave depredations In Apulia, In 8outbern Italy J.T,fne, 1 Jfan'r. Sandy Hoob, Conn. voice of to bring every Into My theories and my It is sad to leave all that is lovely and fair duty faculty conclusions, then, at were allowed to A Year. -

Immortal Song Seventeen Eng Sub 2018

Immortal song seventeen eng sub 2018 Continue Contest South Korean television music program Immortal Songs: Singing LegendGenreMusicPresented Shin Dong-YupCountry OriginsSut Korea Origin (s) Korean No. episodes426 (as of October 19, 2019) ManufacturingInsyant Manufacturer (s)Kwon Yong Taek KBSProduction location (s) South KoreaRunning time110 minutesProduction company (s) KBS EntertainmentReleaseOriginal networkKBSOriginal release4, 2011 - March 31, 2012 (as Immortal Songs 2), April 7, 2012 (2012-04-07) -PresentChronologyPreced byImmortal Songs (2007-2009)External LinksWebsite Immortal Songs: Singing Legends (Korean: 불후의 명곡: 전설을 노래하다; RR: Bulhu-ui Myeong-gok: Jeonseoreul Noraehada), also known as Immortal Song 2 (Korean: 불후의 명곡 2), is a South Korean television music competition program presented by Shin Dong-yup. This is the revival of Immortal Songs (2007-2009), and in each episode there are singers who perform their reimagined versions of the songs. Synopsis Originally aired as Immortal Songs 2 as part of KBS Saturday Freedom, each episode had six idol singers who performed the singer's songs of the episode. After restructuring in 2012, the show returned on April 7 as an independent program and renamed Immortal Songs: Singing the Legend. Each episode now includes seven singers or bands from different walks of life and annual experiences ranging from members of popular idol K-pop bands to legendary solo artists. As before, each of them performs their own reimagined versions of the famous songs of the legendary singer of the episode. The new format features special episodes that revolve around specific topics, such as festivities or festivities. Invited singers sit in the waiting room with three hosts, where they meet the audience. -

Infinite She's Back Korean Version Mp3 Download

infinite she's back korean version mp3 download [Single] Infinite – Be Mine (Japanese) Infinite’s dance hit Be Mine brought them to a new level of popularity in Korea last year. Now they’re bringing the 80s style synth pop number to Japan! Infinite’s second single includes the Japanese-language version of Be Mine, as well as Over the Top and Julia as side tracks. [Single] Infinite – Second Invasion (Live) 인피니트 (Infinite) – Second Invasion (Live) Release Date: 2012.02.24 Language: Korean Genre: Dance Pop Bitrate: 320kbps. Track List: 01 Cover Girl (Live Ver.) [Single] INFINITE – She’s Back [Japanese] INFINITE – She’s Back [Japanese Single] Release Date: 2012.08.29 Genre: J-Pop Language: Japanese Bit Rate: iTunes-M4A-AAC. Infinite’s third Japanese single is a remake of their 2010 summer hit She’s Back. Composed by Sweetune, the uptempo dance song brightens the summer with light beats and a cheery mood. The single’s side tracks are the Japanese version of their debut single To-Ra-Wa (“Come Back Again”) and a Korean remix version of She’s Back. Track List: 01. She’s Back -Japanese Ver.- 02. TO-RA-WA -Japanese Ver.- 03. She’s Back -Koreran Remix Ver.- [Single] Infinite – What is Mom OST Part.1. 인피니트 (Infinite) – 엄마가 뭐길래 OST Part. 1 Release Date: 2012.10.08 Genre: OST Language: Korean Bit Rate: MP3-320kbps. Track List: 01. 환상그녀. [Single] L (INFINITE) & Yerim – Shut Up Flower Boy Band OST Part 5. 엘(인피니트) & 예림(투개월) – 닥치고 꽃미남 밴드 (tvN 월화드라마) Part 5 Release Date: 2012.03.12 Genre: OST: Language: Korean Bit Rate: 320kbps. -

Juvenile Protection and Sexual Objectification: Analysis of the Performance Frame in Korean Music Television Broadcasts1

ACTA KOR ANA VOL. 16, NO. 2, DECEMBER 2013: 329–365 JUVENILE PROTECTION AND SEXUAL OBJECTIFICATION: ANALYSIS OF THE PERFORMANCE FRAME IN KOREAN 1 MUSIC TELEVISION BROADCASTS By CEDARBOUGH T. SAEJI2 The wide-spread sexual objectification of women in Korean popular music performance subconsciously teaches men and boys that women and girls are sexual objects that exist to please them. Simultaneously sexual objectification disempowers girls and women by emphasizing superficial beauty. Although many decisions related to K- pop choreography, costumes, or lyrics may be attributed to music management companies, this article analyzes how music television programs Inkigayo (Seoul Broadcasting System) and Music Core (Munhwa Broadcasting Company) contribute to the sexual objectification of women through the ways that emcees frame performances and the ways the camera draws attention to sexualized body parts. In August 2012 racy performances by the girl group Kara raised public debate and spurred calls for amendments to the Juvenile Protection Law. At that time commentary focused on the impact of sexually provocative performances on young people. The law places responsibility for monitoring content onto the content producers and broadcasters, yet frame analysis of Kara’s performances, compared with performances in early 2013, demonstrated that neither Inkigayo nor Music Core had changed the sexually objectifying performance frame on their shows. The final version of the revised law, 1 This research was supported by Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund of 2013. 2 Author’s Note: Thank you to the editor and enormously helpful anonymous reviewers at Acta Koreana as well as friends and colleagues with whom I discussed aspects of this paper: my gratitude to Logan Clark, Timothy Gitzen, Meredith Perry, Jungwon Kim, Jisoo Hyun, Thea Suh, Go Gwanyeong, and the audience for my presentation at the 2013 International Association for the Study of Popular Music conference. -

L Infinite Love U Like U Mp3 Download

L infinite love u like u mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Infinite Love Songs Download- Listen Infinite Love MP3 songs online free. Play Infinite Love movie songs MP3 by A.R. Rahman feat. Blaaze and download Infinite Love songs on renuzap.podarokideal.ru · Giliran "L" tampil solo di atas panggung. Aduh, gemas banget melihat wajahnya yang ganteng, ditambah lagi suaranya yang bikin hati deg-degan. Dapatkan akses VIP Author: GADISmagz. renuzap.podarokideal.ru - Artis Kim Yerim dan member boyband Infinite, L yang membintangi drama SHUT UP FLOWER BOY BAND bakal merilis single duet pertama mereka. Secara resmi, audio dari single berjudul Love U Like U bakal dirilis pada tanggal 12 Maret.. Single Love U Like U merupakan bagian dari drama yang disiarkan tvN tersebut.L Infinite dan Kim Yerim berhasil menghadirkan cerita cinta tersendiri. L and Kim Yerim – Love U Like U (Eng lyrics + Rom) Posted on Maret 26, by awanderingwonder. 0. I love you, I love you. the words that I can’t bear anymore my trembling heart. the words that I kept hiding in my heart (L & Yerim) Just like the sunshines that glaringly shines on . Fill Your Life with Infinite Love Hypnosis CDs and mp3s, affirmations, subliminal and supraliminal programming - Love is a source of all miracles. 인피니트 H – Fly High [EP] Release Date: Genre: Hip Hop Language: Korean Bit Rate: MPkbps. Fly High with Infinite H! Formed by Infinite’s resident rappers Hoya and Dong Woo, the subunit Infinite H has already impressed fans with performances at their concert tour and the year-end specials. MB. -

Anne Frank's Di

Pakistan School Attack On the 17th December 2014, a greatly upsetting attack took place in Pakistan. Taliban terrorists shot 132 children [aging from twelve to six- teen], ten school staff members, including the principal of the school, and three soldiers in the Army Public School and Degree College. A hundred people were also injured, many having gunshot wounds. It was found out that the terrorists burst into the auditorium where a large number of students were taking an exam and gunned down many of them within minutes. A 14-year-old survivor, Ahmed Faraz, recalled that one of the terrorists ordered his men to kill all the children hiding under the benches. They carried on shooting incessantly. Parents send their children to school expecting them to be safe. How- ever in some countries, school is not as safe as schools in Singapore. So, we should stay alert and be thankful to have this privilege for the safe en- vironment where we study in. It was also said that the students thought that the attack was a drill. As a result, most of them did not take it very seriously. Having said that, many of us tend to take drills in school lightly by joking around and thinking that it is a waste of time. These attacks can be avoided if all of us cooperate and stay united. The root cause of such at- tacks is based on a religion not being accepted by others around them. In this article, we observe that the Islamic culture was not accepted and thus these attacks occurred. -

Of Summit Yjici

Red Cross Drive Red Cross Drive Month of March Month of March S7»K Y-r, No. It SUMMIT, N. J.. THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 1946 Letter From France Htochd SwcctttM Privt 1M7 ffcaitme O« Hospital tart Amos Hiatt Again Root Buys City Hall; Pays Thanks Red Cross Elected President $60,000; Adopt Budget Production taps Adolph Root, president of Roofs Department Store at Sine* VJ Day the R«d Craw Of Summit YJiCi. At a meeting of the Board of Summit, bought the City Hall for $60,000 at a public auc- production Coif* of Summit hat tion held by Common Council Tuesday night. Mr. Root waft tten engaged principally is pro- Directors of the Summit Y. M. ducing garmentu for thi relief of C. A. held immediately following the only bidder. His bid was made by bia counsel. Judge destitute European* in the war the annual dinner meeting on last John L. Hughes. The possession of City; Hall ia to be re* ravaged areas. Letter* from the Thursday, Amos Hlatt was re* talned by the city for a period of seven months from tha recipients have shown their re- elected president of the Summit date of the sale, with the exception of a two-atony build* ipcnsc to tlst fjUla, Association for the coming year. ing containing the firehouse and two apartments for which The following letter waa receiv- Other officers who were also re- elected were Fred L. Palmer, vice- possession will be available not later than October 1,1948. ed from a f*enefc lawyer and has president, Holmes A. -

A Critique of Robert S. Hartman's 'Four Axiological Proofs of the Infinite Value of Man' Raymond M

University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1971 A Critique of Robert S. Hartman's 'Four Axiological Proofs of the Infinite Value of Man' Raymond M. Pruitt University of Tennessee - Knoxville Recommended Citation Pruitt, Raymond M., "A Critique of Robert S. Hartman's 'Four Axiological Proofs of the Infinite Value of Man'. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1971. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3541 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Raymond M. Pruitt ne titled "A Critique of Robert S. Hartman's 'Four Axiological Proofs of the Infinite Value of Man'." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Philosophy. Rem B. Edwards, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: John W. Davis, Dwight Van de Vate, Jr. Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official student records.) November 16, 1971 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Raymond M. Pruitt entitled "A Critique of Robert S. -

MINAT TERHADAP MUSIK KOREA DI KALANGAN REMAJA DI YOGYAKARTA (Studi Pada Penggemar K-Pop Di Daerah Sleman)

MINAT TERHADAP MUSIK KOREA DI KALANGAN REMAJA DI YOGYAKARTA (Studi pada Penggemar K-Pop di Daerah Sleman) SKRIPSI Diajukan Kepada Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta untuk memenuhi Sebagian Persyaratan Guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Ekonomi Disusun Oleh: ANISA NUR ANDINA 08408144033 PROGRAM STUDI MANAJEMEN - JURUSAN MANAJEMEN FAKULTAS EKONOMI UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA 2013 LEMBAR PERSETUJUAN SKRIPSI MINAT TERHADAP MUSIK KOREA DI KALANGAN REMAJA DI YOGYAKARTA (Studi pada Penggemar K-Pop di Daerah Sleman) Disusun Oleh : Anisa Nur Andina NIM. 08408144033 Telah disetujui oleh Dosen Pembimbing untuk diajukan dan dipertahankan di depan Tim Penguji Tugas Akhir Skripsi Jurusan Manajemen, Fakultas Ekonomi, Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta. Yogyakarta, 28 Mei 2013 Menyetujui, Pembimbing Dyna Herlina Suwarto, M.Sc NIP. 19810421 200501 2 001 ii lit PERI\IYATAAN Nama Anisa Nur Andina NIM 08408144033 Prodi/Jurusan Manajernen Fakultas Falarltas Ekonomi Judul Penelitian :Minat Terhadap Musik Korea di Kalangan Remaja di Yogyakarta (Studi pada Penggemar K-Pop di Daerah Sleman). rrya saya sendiri dan sepanjang pengetahuan saya, tidak berisi materi yang dipublikasikan atau ditulis oleh orang lain \ atau telah digunakan sebagai persymatan penyelesaian studi di perguruan tinggi lain, . kecuali pada bagian tertentu yang saya ambil sebagai acuan atau kutipan dengan I mengikuti tata penulisan karya ilmiatr yang telah lazim. i Yogyakarta, 28 Mei 2013 Yang menyatakan, AnisaW Nur Andina NrM.08408144033 IV MOTTO “Kemarin hanya akan menjadi kenangan untuk hari ini dan esok adalah impian untuk hari ini, mari lakukan yang terbaik” (Penulis) “Patience is bitter, but it’s fruit is sweet” (Jang Dongwoo - Infinite) “Hai orang-orang beriman, jadikan sabar dan shalatmu sebagai penolongmu, sesungguhnya Allah beserta orang-orang yang sabar” (Al Baqarah: 153) “Pendidikan adalah mempelajari apa yang bahkan kau tak tahu dari apa yang tak kau ketahui” ( Daniel J.