The Review of International Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLICE FORCES to the BORDER! HUNGARY COMES FULL CIRCLE on OPEN BORDERS by John R

JUNE 2015 POLICE FORCES TO THE BORDER! HUNGARY COMES FULL CIRCLE ON OPEN BORDERS By John R. Haines John R. Haines is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute and Executive Director of FPRI's Princeton Committee. Much of his current research is focused on Russia and its near abroad, with a special interest in nationalist and separatist movements. As a private investor and entrepreneur, he is currently focused on the question of nuclear smuggling and terrorism, and the development of technologies to discover, detect, and characterize concealed fissile material. He is also a Trustee of FPRI. For other nations, their land has fixed boundaries. For Rome, its boundaries are the boundaries of the Roman world.1 So, too, it seems, for the nations of the European Community, and for the Community itself. And that is the basis of the immigration crisis now raging in Hungary. When the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November 1989—Der Mauerfall to Germans—it set the two Germanys on a course to reunification eleven months later. It was in Hungary, however, where “the first stone was knocked out of the wall,” declared Helmut Kohl. In June 1989 Hungarian foreign minister Gyula Horn and his Austrian counterpart, Alois Mock used wire cutters to cut a symbolic section of the barbed wire fence separating their two countries. The next month, a small group of Hungarian dissidents and Austrian politicians organized what they intended would be a symbolic border opening outside the Hungarian border village of Sopronpuszta. The opening became more than symbolic: within a few hours, some 600 East Germans passed through a simple wooden gate into Austria. -

Collection of Policy Papers on Police Reform in Serbia

COLLECTION OF Number 5 July 2011 POLICY PAPERS ON POLICE REFORM IN SERBIA www.ccmr-bg.org Belgrade Centre for Security Policy www.bgcentar.org.rs Belgrade Centre for Human Rights COLLECTION OF POLICY PAPERS ON POLICE REFORM IN SERBIA NUMBER 5 JULY 2011 Authors: Jan Litavski Saša Đorđević Žarko Marković In front of you is fifth Collection of Policy Papers on Police Reform in Serbia which is the result of joint work of two CSOs: the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, and the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights. It is a part of the project “Fostering Civil Society Involvement in Police Reform” supported by the OSCE Mission to Serbia, the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Geneva Centre for Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF). The views expressed herein are those merely of the three research- ers from the CSOs in Serbia and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the OSCE Mission to Serbia, the Embassy of the Netherlands and the Geneva Centre for Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF). Collection of Policy Papers on Police Reform in Serbia Number 5, July 2011 Authors: Jan Litavski Saša Đorđević Žarko Marković Publishers: Belgrade Centre for Security Policy Gundulićev venac 48, Belgrade Tel: 011 | 32 87 226; 32 87 334 Email: [email protected] www.bezbednost.org | www.ccmr-bg.org Belgrade Centre for Human Rights Beogradska 54, Beograd Tel: 011 | 30 85 328; 34 47 121 Email: [email protected] www.bgcentar.org.rs Design and type settings: Saša Đorđević Coverpage (photographies): Ethics (2011) [Phi2010.com]; Networking (2010) [Techgenie.com]; Illegal migrants from Africa (2011) [Allvoices.com]; Serbian Police officers (2011) [Kurir.rs]; Exchange of Information (2011) [Dreamstime.com]; Illegal migrants in Europe (2011) [Guardian.co.uk] Print run: 200 Published with the support of the Mission OSCE to Serbia, the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Geneva Centre for Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF). -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Council of Ministers

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA COUNCIL OF MINISTERS SECOND READINESS REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ROAD MAP FOR VIZA LIBERALIZATION Sarajevo, 1 October 2009 CONTENT BLOCK 1 – Document Security ................................................................................................... 3 BLOCK 2 - Illegal migration, including readmission ................................................................ 7 BLOCK 3 - Public order and security……………………………………..………………...… 18 BLOCK 4 - External relations and fundamental rights………………...…………………….. 63 ANNEX 1 – Migration Profile of Bosnia and Herzegovina …………………………………... 65 ANNEX 2 – Returnee Reintegration Strategy…………………………………………………131 ANNEX 3 – Strategy for Combating Organized Crime…………………………………....... 167 ANNEX 4 – Strategy and Action Plan for the Prevention of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorist Activities in Bosnia and Herzegovina………………....190 ANNEX 5 – National Anti-Corruption Strategy and Action Plan…………………………...217 ANNEX 6 – Draft Law on Amendments to the Criminal Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina …………………………………………………………242 ANNEX 7 – Draft Law on Agency for Prevention of Corruption and on Cooperation in Fight of Corruption……………………………………………………………281 ANNEX 8 – Law on Prohibition of Discrimination…………………………………...………290 ANNEX 9 - Bosnia and Herzegovina Chief Prosecutor Report...............................................301 ANNEX 10 – Information on the situation in the Institution of Human Rights Ombudsman for Bosnia and Herzegovina………………………………..……308 2 BLOCK 1 Document Security Passports/travel -

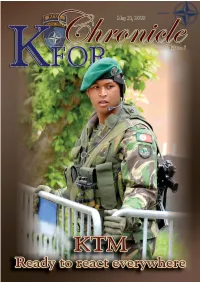

Kfor Chronicle

KFOR CHRONICLE By MAJ Jo Schöpf, PhD, AUT A Photos by Armend Aqifi On October 5, KFOR Exercise KFOR multinational units. "Balkan Hawk" was conducted at "This is a warning for those who Camp Vrelo. oppose to peace and stability in This exercise was to demonstrate Kosovo that NATO is ready, willing KFOR readiness in dealing with and able to fulfill its mandate," said potential conflict in Kosovo and to LTG Giuseppe Valotto, COMKFOR. test the interoperability, sustainability and capabilities of its units. One of the exercise scenarios was in active- ly displayed the KFOR ability of crowd riot control. Impressively as troops to rapidly deploy and settle conflicts in order to maintain a safe and secure environment for Kosovo in accordance with UNSCR 1244. The exercise was in close coopera- tion between Kosovo Police Service (KPS), Multinational Specialized Unit (MSU), UNMIK-Police, KFOR Tactical Maneuver Battalion (KTM) and the German and Italian Operational Reserve Force (ORF) Battalion. Approximately 400 peacekeepers took part in the operation designed to respond to riots or other violence that threatens to flare up in the province, run by the UN and NATO since Kosovo's 1998-1999 war. The exercise was in several steps. The scenario was based on a simulated demonstration against an International organization. The Danish and American soldiers who were acting as demonstrators were instructed to be violent and that the violence should escalate more and more. The demonstrators played their role very convincingly. Soon enough the headquarter was threat- ened. At this stage support was requested. Helicopters transported reinforcements from the Portuguese army as the KPS and KFOR soldiers attempted to keep a riot in check. -

Chapter 24: Justice, Freedom and Security

Chapter 24: Justice, freedom and security EU policies aim to maintain and further develop the Union as an area of freedom, security and justice. On issues such as border control, visas, external migration, asylum, police cooperation, the fight against organised crime and against terrorism, cooperation in the field of drugs, customs cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal and civil matters, Member States need to be properly equipped to adequately implement the growing framework of common rules. Above all, this requires a strong and well-integrated administrative capacity within the law enforcement agencies and other relevant bodies, which must attain the necessary standards. A professional, reliable and efficient police organisation is of paramount importance. The most detailed part of the EU’s policies on justice, freedom and security is the Schengen acquis, which entails the lifting of internal border controls in the EU. However, for the new Member States substantial parts of the Schengen acquis are implemented following a separate Council Decision to be taken after accession. 1 Migration 1. Please provide information on general immigration policy, as well as legislation or other rules governing migration in your country. Migration policy in the Republic of Serbia is defined in accordance with the achievements of international law in the domain of human protection, proclaimed by agreements between the UN Member States (ratified by our country), such as: Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons (1959), Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (1963), Convention on the Status of Refugees (1963), International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1971), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1971) and other conventions. -

Annual Report of the Secretary General on Police-Related Activities 2015

Annual Report of the Secretary General on Police-Related Activities 2015 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe is The World’s Largest Regional Security Organization working to ensure peace, democracy and stability for more than a billion people between Vancouver and Vladivostok. This report is submitted in accordance with Decision 9, paragraph 6, of the Bucharest Ministerial Council Meeting, 4 December 2001 © OSCE 2016 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction be accompanied by an acknowled- gement of the OSCE as the source. OSCE Secretariat Transnational Threats Department Strategic Police Matters Unit Wallnerstrasse 6 1010 Vienna, Austria SEC.DOC/2/16 21 July 2016 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.osce.org/secretariat/policing http://polis.osce.org Original: ENGLISH Table of Contents Preface by the OSCE Secretary General 2 Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 9 2. Activities of the Transnational Threats Department 13 2.1 TNTD/Co-ordination Cell 15 2.2 TNTD/Strategic Police Matters Unit 16 2.3 TNTD/Action against Terrorism Unit 24 2.4 TNTD/Borders Security and Management Unit 27 3. Police-Related Activities of other Thematic Units 31 3.1 Gender Section 32 3.2 Office of the Co-ordinator of Economic and Environmental Activities 33 3.3 Office of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings 34 4. Police-Related -

Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL

2021 1-2. Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 _ CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL Number 1-2 Volume III. February 2021 ISSN 2676-9778 GÁBOR ANDROVICZ: Service placement and housing conditions of the Budapest police staff from the 1880s to the 1930s SZABOLCS MÁTYÁS – ZSOLT LIPPAI – ÁGOTA NÉMETH – PÉTER FELFÖLDI – IVETT NAGY – ERIKA GÁL: Criminal geographical analysis of cycling accidents in Budapest ANDREA PŐDÖR: Investigation of different visualisation methods for crime mapping MÁTÉ SIVADÓ: The basic patterns of drug use are in some parts of the world and the possible causes of differences Abstracts of the 1st Criminal Geography Conference of the Hungarian Assocation of Police Science Hungarian Association of Police Science 1 Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 CGJ ___________________________________________________________________________ CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL ___________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC AND APPLIED RESEARC IN CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHY SCIENCE VOLUME III / NUMBER 1-2 / FEBRUARY 2021 2 Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 Academic and applied research in criminal geography science. CGR is a peer-reviewed international scientific journal. Published four times a year. Chairman of the editorial board: SZABOLCS MÁTYÁS Ph.D. assistant professor (University of Public Service, Hungary) Honorary chairman of the editorial board: JÁNOS SALLAI Ph.D. professor (University of Public Service, Hungary) Editor in chief: VINCE VÁRI Ph.D. assistant professor (University of Public Service, Hungary) Editorial board: UFUK AYHAN Ph.D. associate professor (Turkish National Police Academy, Turkey) MARJAN GJUROVSKI Ph.D. assistant professor (State University ’St. Kliment Ohridski’, Macedonia) LADISLAV IGENYES Ph.D. assistant professor (Academy of the Police Force in Bratislava, Slovakia) IVAN M. KLEYMENOV Ph.D. professor (National Research University Higher School of Economics, Russia) KRISTINA A. -

CHRONICLE 05.Qxp

[Commentary] CCoonnttiinnuuee ttoo lliigghhtt tthhee wwaayy ttoo aa bbrriigghhtteerr ffuuttuurree As I close in on a full year here on the ground in Kosovo I cannot help but think what KFOR has been through over the past eleven months. Together, the KFOR Team has seen many historical moments and all along the KFOR Soldier, Sailor, Airman, Marine, and Civilian employee have served proudly and with distinction. Coming from 33 different Nations and varied backgrounds and experiences, you have come together here in Kosovo for the one mission we have had since 1999: to maintain the Safe and Secure environment for all of Kosovo. Through your actions you continue to light the way to a brighter future for all the people here. These gains were not made without sacrifices and while you have been separated from your loved ones for months at a time, you have continued to serve proudly, with distinction and always with a smile on your face. All of you have worked through many long days and nights, and many fought to quell the violence of March 17th, but through it all, you have served proudly and honorably with dedication and courage. It has been a great personal and professional honor to serve with the entire KFOR Team over this past year. I thank all of you for your sacrifices, your hard work, and your professionalism and I pray that this experience proves to be a lasting blessing for all of you, your families, and for all the citizens of Kosovo. Brigadier General William T. Wolf, U.S. -

Crimen 2021-01

UDK: 343.13:351.746.2(439) doi: 10.5937/crimen2101023C Originalni nauni rad primljen / prihvaen: 14.02.2021. / 02.04. 2021. Dragana Čvorović* University of Criminal Investigation and Police Studies, Serbia Vince Vári** University of Public Service, Faculty of Law, Hungary POLICE IN THE HUNGARIAN CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS Abstract: The police play a key role in the Hungarian criminal justice system. In addition to the legality supervision and effective professional management of the prosecution, the police have performed investigative tasks, which has procedural autonomy in initiating differentiated procedural methods in the reconnaissance and examination phase. The investigation consists of reconnaissance and investigation. In contrast, in the examination phase, they work under the direction of the prosecution. In addition to the general police, there are special police bodies in the country that do not have investigative powers but can take part in the preparatory process at the initial stage of the investigation, in particular by collecting data to establish the suspicion of a crime. Such bodies are the National Defense Service for Internal Corruption and Terrorism and the Counter-Terrorism Center. In our article, we provide an overview of the role of the police in a state organization. In accordance with that, we analyze the police’s law enforcement role, outline the investigative activities of the Hungarian police and their tasks in criminal proceedings. Keywords: police, criminal proceedings, investigation, prosecution, reconnaissance, exami- nation. THE PLACE OF THE POLICE IN THE STATE ORGANIZATION Introductory remarks) In the post-compromise era of the development of the Hungarian public ad- ministration, the police gradually became a modern public administration body and gained a place in the public administration. -

Annual Report 2015

2015 ODIHR OSCE OFFICE FOR DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS Annual Report 2015 ANNUAL REPORT ODIHR OSCE OFFICE FOR DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS Annual Report 2015 Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10 00-251 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2016 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ODIHR as the source. ISBN 978-92-9234-938-7 Designed by Nona Reuter Printed in Poland by Poligrafus Jacek Adamiak Contents Overview by the ODIHR Director 04 Elections 08 Democratization 14 Human Rights 26 Tolerance and Non-Discrimination 32 Contact Point for Roma and Sinti Issues 38 Human Dimension Meetings 2015 44 Selected 2015 Conferences and Meetings 47 Extrabudgetary Programmes and Projects 2015 54 Legislative Reviews in 2015 59 2015 Publications 60 Election Reports and Statements Released in 2015 61 ODIHR Structure and Budget 63 4 • Elections Overview by the ODIHR Director Overview • 5 OSCE/ODIHR Director Michael Georg Link, speaking at the Supplementary Human Dimension Meeting on OSCE Contribution to the Protection of National Minorities, in Vienna, 29 October 2015 OSCE/ Micky Amon-Kröll The 57 participating States that make participating States whenever and of human rights. In 2015 alone, over up the Organization for Security and wherever the rights of marginalized 500 of Ukrainian stakeholders bene- Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) contin- individuals are at stake. All participat- fited from training events on human ued to face challenges to the imple- ing States have recognized that their rights monitoring and hate crime, mentation of their human dimension commitments to strengthen democra- workshops on political party financing, commitments in 2015. -

DCAF Annual Report 2017

DCAF DCAF AnnualAnnex to Report the DCAF 2017 PerformanceDedicated to making Report states 2017 Keyand Activitiespeople safer per through Project/Programme more effective and accountable security and justice CONTENTS Table III.1: Southeast Europe – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ........................................................ 1 Table III.2: Middle East and North Africa – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ........................................ 5 Table III.3: Sub-Saharan Africa – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 .................................................... 12 Table III.4: Eastern Europe/South Caucasus/Central Asia – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 .......... 15 Table III.5: Asia-Pacific – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ................................................................ 17 Table III.6: Latin America and the Caribbean – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ............................... 19 Table III.7: Bilateral Donors – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 .......................................................... 20 Table III.8: Multilateral Organizations – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ........................................... 21 Table III.9: Other Multilateral Platforms – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ........................................ 26 Table III.10: Security Governance – Key activities by project/programme in 2017 ................................................ 27 Table III.11: Gender and Security -

Opinion on the Draft Law on Police of Serbia

Warsaw, 7 October 2015 Opinion-Nr.: GEN-SRB/275/2015 [AlC] www.legislationline.org OPINION ON THE DRAFT LAW ON POLICE OF SERBIA based on an unofficial English translation of the draft law provided by the OSCE Mission to Serbia This Opinion has benefited from contributions made by the OSCE Strategic Police Matters Unit, Transnational Threats Department, of the OSCE Secretariat and by Dr. Andy Aitchison, Lecturer in Criminology (University of Edinburgh) and Researcher on Criminal Justice in Transitional States OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights Ulica Miodowa 10 PL-00-251 Warsaw ph. +48 22 520 06 00 fax. +48 22 520 0605 OSCE/ODIHR Opinion on the Draft Law on Police of Serbia TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 II. SCOPE OF REVIEW ................................................................................. 3 III. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................... 3 IV. ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................. 5 1. International Standards on Democratic Policing ........................................................ 5 2. General Comments ......................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Purpose and Scope of the Draft Law ............................................................................... 7 2.2. Linkages between the Draft Law and the Code of Criminal Procedure .........................