Hutton's Contribution to the Invention of Contours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Mathematical Journal and Its Descendants: the Linchpin of a Research Community in the Early and Mid-Victorian Age ✩

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematica 31 (2004) 455–497 www.elsevier.com/locate/hm The Cambridge Mathematical Journal and its descendants: the linchpin of a research community in the early and mid-Victorian Age ✩ Tony Crilly ∗ Middlesex University Business School, Hendon, London NW4 4BT, UK Received 29 October 2002; revised 12 November 2003; accepted 8 March 2004 Abstract The Cambridge Mathematical Journal and its successors, the Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal,and the Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, were a vital link in the establishment of a research ethos in British mathematics in the period 1837–1870. From the beginning, the tension between academic objectives and economic viability shaped the often precarious existence of this line of communication between practitioners. Utilizing archival material, this paper presents episodes in the setting up and maintenance of these journals during their formative years. 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Résumé Dans la période 1837–1870, le Cambridge Mathematical Journal et les revues qui lui ont succédé, le Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal et le Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, ont joué un rôle essentiel pour promouvoir une culture de recherche dans les mathématiques britanniques. Dès le début, la tension entre les objectifs intellectuels et la rentabilité économique marqua l’existence, souvent précaire, de ce moyen de communication entre professionnels. Sur la base de documents d’archives, cet article présente les épisodes importants dans la création et l’existence de ces revues. 2004 Elsevier Inc. -

Edwin Danson, UK: the Work of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon

The Work of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon Edwin DANSON, United Kingdom Key words: Mason, Charles; Dixon, Jeremiah; Mason-Dixon Line; Pre-revolutionary History; Surveying; Geodesy; US History; Pennsylvania; Maryland. ABSTRACT The geodetic activities of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon in America between 1763-68 were, for the period, without precedent. Their famous boundary dividing Maryland from Pennsylvania, the Mason-Dixon Line, today remains a fitting monument to these two brave, resourceful and extremely talented scientists. Tutored by Astronomer Royal Dr James Bradley, Charles Mason was aware of the contemporary theories and experiments to establish the true shape of the Earth. He was also cognisant of what was being termed “the attraction of mountains” (deviation of the vertical). However, at the time it was no more than a theory, a possibility, and it was by no means certain whether the Earth was solid or hollow. The Mason-Dixon Line, a line of constant latitude fifteen miles south of Philadelphia, although the most arduous of their tasks, was only part of their work for the proprietors of Maryland and Pennsylvania. For the Royal Society of London, they also measured the first degree of latitude in America. In recent years, the Mason-Dixon Line Preservation Partnership has located many of the original markers and surveyed them using GPS. The paper reviews the work of Mason and Dixon covering the period 1756-1786. In particular, their methods and results for the American boundary lines are discussed together with comments on the accuracy they achieved compared with GPS observations. CONTACT Edwin Danson 14 Sword Gardens Swindon, SN5 8ZE UNITED KINGDOM Tel. -

Articles Articles

Articles Articles ALEXI BAKER “Precision,” “Perfection,” and the Reality of British Scientific Instruments on the Move During the 18th Century Résumé Abstract On représente souvent les instruments scientifiques Early modern British “scientific” instruments, including du 18e siècle, y compris les chronomètres de précision, precision timekeepers, are often represented as static, comme des objets statiques, à l’état neuf et complets en pristine, and self-contained in 18th-century depictions eux-mêmes dans les descriptions des débuts de l’époque and in many modern museum displays. In reality, they moderne et dans de nombreuses expositions muséales were almost constantly in physical flux. Movement and d’aujourd’hui. En réalité, ces instruments se trouvaient changing and challenging environmental conditions presque constamment soumis à des courants physiques. frequently impaired their usage and maintenance, Le mouvement et les conditions environnementales especially at sea and on expeditions of “science” and difficiles et changeantes perturbaient souvent leur exploration. As a result, individuals’ experiences with utilisation et leur entretien, en particulier en mer et mending and adapting instruments greatly defined the lors d’expéditions scientifiques et d’exploration. Ce culture of technology and its use as well as later efforts sont donc les expériences individuelles de réparation at standardization. et d’adaptation des instruments qui ont grandement contribué à définir la culture de la technologie. In 1769, the astronomer John Bradley finally the calculation of the distance between the Earth reached the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall and the Sun. Bradley had not needed to travel with his men, instruments, and portable tent as far as many of his Transit counterparts, but observatory after a stressful journey. -

Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in: Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa40899 _____________________________________________________________ Paper: Tucker, J. Richard Price and the History of Science. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 23, 69- 86. _____________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ 69 RICHARD PRICE AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE John V. Tucker Abstract Richard Price (1723–1791) was born in south Wales and practised as a minister of religion in London. He was also a keen scientist who wrote extensively about mathematics, astronomy, and electricity, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in support of a national history of science for Wales, this article explores the legacy of Richard Price and his considerable contribution to science and the intellectual history of Wales. -

Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches Within the New Digital History (Pp

CHAPTER 14 The Many Ways to Talk about the Transits of Venus Astronomical Discourses in Philosophical Transactions, 1753–1777 Reetta Sippola A Popular Astronomical Event In the 1760s, one of astronomy’s rarest predictable phenomena, the so-called Transit of Venus, was calculated to take place twice: in 1761 and in 1769. This phenomenon, when the planet Venus passes across the Sun, from the Earth’s vantage point, was not only extremely rare, as the previous transit had taken place in 1639 and the next was to follow in 1874, but also very valuable scien- tifically, as observing this kind of transit would make it possible to determine the distance between the Earth and the Sun more accurately than before. This could in turn make it easier to improve a number of practical issues relying on astronomical knowledge, foremost among them to improve the accuracy of calculating locations at sea, which at this time was at best inaccurate, often resulting in costly and deadly accidents. Thus, the two Transit of Venus events and the astronomical information that could be derived from observing them enjoyed wide interest among both scientific professionals and the general How to cite this book chapter: Sippola, R. (2020). The many ways to talk about the Transits of Venus: Astronomical discourses in Philosophical Transactions, 1753–1777. In M. Fridlund, M. Oiva, & P. Paju (Eds.), Digital histories: Emergent approaches within the new digital history (pp. 237–257). Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. https://doi.org/10.33134 /HUP-5-14 238 Digital Histories public. The scientific interest in the transits during the 18th century was rep- resented through a large number of news items and scientific reports in the scientific literature, especially in scientific periodicals, such as thePhilosophi - cal Transactions of the Royal Society of London. -

Reconstructing the Lost Contours of Charles Hutton

Reconstructing the lost contours of Charles Hutton Karen Rann a, David Fairbairn b, *, Ella Southern c a Queens University, Belfast, UK; [email protected] b Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; [email protected] c Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; [email protected] * Corresponding author Keywords: Historical land surveying, contour mapping This study reports on an historical investigation of map-making practice and achievement from the late 18th century, and attempts to reconstruct the practices and outcomes of an innovative surveying and mapping exercise, using historical data and contemporary geospatial data handling. The episode involves the processing of data captured as part of an extensive project by the then (British) Astronomer Royal, Maskelyne, in the mid 1770s, to measure the gravitational attraction and density of the earth. This experiment was conducted on the isolated mountain of Schiehallion in Central Scotland, and resulted in several differing approaches to calculating the mass of the mountain, and determining and interpreting the resultant effect on gravity measurements on its slopes. In order to do this, an accurate determination of “the figure and dimensions of the hill” (Maskelyne, 1775) was required. The survey work was undertaken under Maskelyne’s supervision by his previous assistant, Barrow, and local surveyor, Menzies. The data collected included astronomical observations to establish latitudinal positions, lengths of fixed base lines (one to the north of the mountain and one to the south), a standard traverse around the mountain to establish fixed points, and transects/vertical profiles radiating from those points. The land surveying techniques were known and widely used, although at the time having only been recently documented, in the book ‘A Treatise on Mensuration’. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Reconstructing the Lost Contours of Charles Hutton

Reconstructing the lost contours of Charles Hutton Karen Rann a, David Fairbairn b, *, Ella Southern c a Queens University, Belfast, UK; [email protected] b Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; [email protected] c Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; [email protected] * Corresponding author Keywords: Historical land surveying, contour mapping This study reports on an historical investigation of map-making practice and achievement from the late 18th century, and attempts to reconstruct the practices and outcomes of an innovative surveying and mapping exercise, using historical data and contemporary geospatial data handling. The episode involves the processing of data captured as part of an extensive project by the then (British) Astronomer Royal, Maskelyne, in the mid 1770s, to measure the gravitational attraction and density of the earth. This experiment was conducted on the isolated mountain of Schiehallion in Central Scotland, and resulted in several differing approaches to calculating the mass of the mountain, and determining and interpreting the resultant effect on gravity measurements on its slopes. In order to do this, an accurate determination of “the figure and dimensions of the hill” (Maskelyne, 1775) was required. The survey work was undertaken under Maskelyne’s supervision by his previous assistant, Barrow, and local surveyor, Menzies. The data collected included astronomical observations to establish latitudinal positions, lengths of fixed base lines (one to the north of the mountain and one to the south), a standard traverse around the mountain to establish fixed points, and transects/vertical profiles radiating from those points. The land surveying techniques were known and widely used, although at the time having only been recently documented, in the book ‘A Treatise on Mensuration’. -

Charles Hutton: Scientist, Mathematician and the Density of the Earth

Charles Hutton: scientist, mathematician and the density of the Earth Robin Johnson Outline his life his science his mathematics & teaching the Schiehallion experiment overview & summary 2 Charles Hutton: his life 3 Born on Percy Street; father Henry, mother Eleanor. Taught to read (Percy St.), and then to write (Benwell). Educated at Rev. Mr. Ivison’s school in Jesmond – and he then took over the school. 1737-1823 He moved the school to Stotes Hall, with three further moves as the school expanded. 3 Teaching by day, studying mathematics in the 4 evenings at Mr. James’ Mathematical School in Newcastle. Started teaching at the school; married Isabella in 1760; took over the school (advert). Pupils included John Scott (later Lord Eldon, Lord High Chancellor of England), his wife-to-be Elizabeth Surtees, and the children of Robert Shafto. 4 In 1773, he was appointed 5 Professor of Mathematics at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich. Left Isabella and his children in Newcastle. Elected to the Royal Society in 1774, and was its foreign secretary 1779-’83. 5 Isabella died in 1785; he remarried (Margaret). 6 Four daughters by first wife and one by his second, but two predeceased him. In 1786 he began to suffer from pulmonary disorders, so decided to move away from the Thames. New Royal Military Academy – closed in 1939 by Andrew Morton (1802–1845) 6 Ill health forced him to resign his Chair in 1807; he died in 1823. 7 In his last year, a fund was set up to honour him: to cover the cost of a marble bust and, so much was raised, also a medal. -

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective Larry McHenry The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? A: Kepler’s Prediction – 1627: B: 1st Transit Observation – Jeremiah Horrocks 1639 2) Why was it so Important? A: Edmund Halley’s call to action 1716 B: The Age of Reason (Enlightenment) and the start of the Industrial Revolution 3) The First World Wide effort – the Transit of 1761. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 4) The Second Try – the Transit of 1769. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 5) The 19th Century attempts – 1874 Transit A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 6) The 19th Century’s Last Try – 1882 Transit - Photography will save the day. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 7) The Modern Era A: Now it’s just for fun: The AU has been calculated by other means). B: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation C: My personal experience – 2004 D: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation…Cont. E: My personal experience - 2012 F: New Science from the Transit 8) Conclusion – What Next – 2117. Credits The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? Introduction: Last June, 2012, for only the 7th time in recorded history, a rare celestial event was witnessed by millions around the world. This was the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the Sun. -

James Hutton's Reputation Among Geologists in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

The Geological Society of America Memoir 216 Revising the Revisions: James Hutton’s Reputation among Geologists in the Late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries A. M. Celâl Şengör* İTÜ Avrasya Yerbilimleri Enstitüsü ve Maden Fakültesi, Jeoloji Bölümü, Ayazağa 34469 İstanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT A recent fad in the historiography of geology is to consider the Scottish polymath James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth the last of the “theories of the earth” genre of publications that had begun developing in the seventeenth century and to regard it as something behind the times already in the late eighteenth century and which was subsequently remembered only because some later geologists, particularly Hutton’s countryman Sir Archibald Geikie, found it convenient to represent it as a precursor of the prevailing opinions of the day. By contrast, the available documentation, pub- lished and unpublished, shows that Hutton’s theory was considered as something completely new by his contemporaries, very different from anything that preceded it, whether they agreed with him or not, and that it was widely discussed both in his own country and abroad—from St. Petersburg through Europe to New York. By the end of the third decade in the nineteenth century, many very respectable geologists began seeing in him “the father of modern geology” even before Sir Archibald was born (in 1835). Before long, even popular books on geology and general encyclopedias began spreading the same conviction. A review of the geological literature of the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries shows that Hutton was not only remembered, but his ideas were in fact considered part of the current science and discussed accord- ingly. -

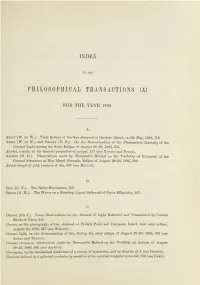

Philosophical Transactions (A)

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1889. A. A bney (W. de W.). Total Eclipse of the San observed at Caroline Island, on 6th May, 1883, 119. A bney (W. de W.) and T horpe (T. E.). On the Determination of the Photometric Intensity of the Coronal Light during the Solar Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363. Alcohol, a study of the thermal properties of propyl, 137 (see R amsay and Y oung). Archer (R. H.). Observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of Extension of the Coronal Streamers at Hog Island, Grenada, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382. Atomic weight of gold, revision of the, 395 (see Mallet). B. B oys (C. V.). The Radio-Micrometer, 159. B ryan (G. H.). The Waves on a Rotating Liquid Spheroid of Finite Ellipticity, 187. C. Conroy (Sir J.). Some Observations on the Amount of Light Reflected and Transmitted by Certain 'Kinds of Glass, 245. Corona, on the photographs of the, obtained at Prickly Point and Carriacou Island, total solar eclipse, August 29, 1886, 347 (see W esley). Coronal light, on the determination of the, during the solar eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363 (see Abney and Thorpe). Coronal streamers, observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382 (see A rcher). Cosmogony, on the mechanical conditions of a swarm of meteorites, and on theories of, 1 (see Darwin). Currents induced in a spherical conductor by variation of an external magnetic potential, 513 (see Lamb). 520 INDEX.