William Dawes' Gravity Measurement in Sydney Cove, 1788

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vicious Circle”: Unscrambling A.-C

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 15 t 19881, 228-239 Breaking a “Vicious Circle”: Unscrambling A.-C. Clairaut’s Iterative Method of 1743 JOHN L. GREENBERG Centre de Recherches Alexar~dre KoyrC, 12. rue Colherf. 75.002 Puris. FI.N~C.C In this paper 1 show how in 1743 A.-C. Clairaut applied an iterative method to calculate the ellipticity of an infinitesimally flattened, homogeneous ellipsoid of revolution in equilib- rium, taken to represent the earth. Clairaut did not make very clear what he was doing and, as a result, left certain readers in the dark. They could not understand the point of the calculation and erroneously thought that Clairaut was going around in circles. The paper ends with a discussion of Clairaut’s clarification of the calculation, published in 1760 in response to the criticisms of John Muller, and a brief comparison of Clairaut’s iterative method with the “Newton-Raphson Method.” 1 1988.4cademlc Pres\. Inc. Dans cet article je montre la methode d’approximation d’A.-C. Clairaut pour trouver I’ellipticite d’un ellipsoi’de homogene de revolution en equilibre dont l’ellipticitt est infinite- simale et qui reprtsente la terre. Certains lecteurs ont mal compris Clairaut. Ceux-ci ont cru Clairaut pris au piege dans un “cercle vicieux en logique.” Clairaut a repondu a son critique John Muller en 1760, et j’explique cette reponse. Mon article se termine par une breve comparaison de la methode de Clairaut et de celle dite “Newton-Raphson.” Cette com- paraison peut eclairer la cause du malentendu. -

Edwin Danson, UK: the Work of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon

The Work of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon Edwin DANSON, United Kingdom Key words: Mason, Charles; Dixon, Jeremiah; Mason-Dixon Line; Pre-revolutionary History; Surveying; Geodesy; US History; Pennsylvania; Maryland. ABSTRACT The geodetic activities of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon in America between 1763-68 were, for the period, without precedent. Their famous boundary dividing Maryland from Pennsylvania, the Mason-Dixon Line, today remains a fitting monument to these two brave, resourceful and extremely talented scientists. Tutored by Astronomer Royal Dr James Bradley, Charles Mason was aware of the contemporary theories and experiments to establish the true shape of the Earth. He was also cognisant of what was being termed “the attraction of mountains” (deviation of the vertical). However, at the time it was no more than a theory, a possibility, and it was by no means certain whether the Earth was solid or hollow. The Mason-Dixon Line, a line of constant latitude fifteen miles south of Philadelphia, although the most arduous of their tasks, was only part of their work for the proprietors of Maryland and Pennsylvania. For the Royal Society of London, they also measured the first degree of latitude in America. In recent years, the Mason-Dixon Line Preservation Partnership has located many of the original markers and surveyed them using GPS. The paper reviews the work of Mason and Dixon covering the period 1756-1786. In particular, their methods and results for the American boundary lines are discussed together with comments on the accuracy they achieved compared with GPS observations. CONTACT Edwin Danson 14 Sword Gardens Swindon, SN5 8ZE UNITED KINGDOM Tel. -

Redalyc.The International Pendulum Project

Revista Electrónica de Investigación en Educación en Ciencias E-ISSN: 1850-6666 [email protected] Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires Argentina Matthews, Michael R. The International Pendulum Project Revista Electrónica de Investigación en Educación en Ciencias, vol. 1, núm. 1, octubre, 2006, pp. 1-5 Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=273320433002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Año 1 – Número 1 – Octubre de 2006 ISSN: en trámite The International Pendulum Project Michael R. Matthews [email protected] School of Education, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia The Pendulum in Modern Science Galileo in his final great work, The Two New Sciences , written during the period of house arrest after the trial that, for many, marked the beginning of the Modern Age, wrote: We come now to the other questions, relating to pendulums, a subject which may appear to many exceedingly arid, especially to those philosophers who are continually occupied with the more profound questions of nature. Nevertheless, the problem is one which I do not scorn. I am encouraged by the example of Aristotle whom I admire especially because he did not fail to discuss every subject which he thought in any degree worthy of consideration. (Galileo 1638/1954, pp.94-95) This was the pendulum’s low-key introduction to the stage of modern science and modern society. -

Articles Articles

Articles Articles ALEXI BAKER “Precision,” “Perfection,” and the Reality of British Scientific Instruments on the Move During the 18th Century Résumé Abstract On représente souvent les instruments scientifiques Early modern British “scientific” instruments, including du 18e siècle, y compris les chronomètres de précision, precision timekeepers, are often represented as static, comme des objets statiques, à l’état neuf et complets en pristine, and self-contained in 18th-century depictions eux-mêmes dans les descriptions des débuts de l’époque and in many modern museum displays. In reality, they moderne et dans de nombreuses expositions muséales were almost constantly in physical flux. Movement and d’aujourd’hui. En réalité, ces instruments se trouvaient changing and challenging environmental conditions presque constamment soumis à des courants physiques. frequently impaired their usage and maintenance, Le mouvement et les conditions environnementales especially at sea and on expeditions of “science” and difficiles et changeantes perturbaient souvent leur exploration. As a result, individuals’ experiences with utilisation et leur entretien, en particulier en mer et mending and adapting instruments greatly defined the lors d’expéditions scientifiques et d’exploration. Ce culture of technology and its use as well as later efforts sont donc les expériences individuelles de réparation at standardization. et d’adaptation des instruments qui ont grandement contribué à définir la culture de la technologie. In 1769, the astronomer John Bradley finally the calculation of the distance between the Earth reached the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall and the Sun. Bradley had not needed to travel with his men, instruments, and portable tent as far as many of his Transit counterparts, but observatory after a stressful journey. -

Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in: Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa40899 _____________________________________________________________ Paper: Tucker, J. Richard Price and the History of Science. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 23, 69- 86. _____________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ 69 RICHARD PRICE AND THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE John V. Tucker Abstract Richard Price (1723–1791) was born in south Wales and practised as a minister of religion in London. He was also a keen scientist who wrote extensively about mathematics, astronomy, and electricity, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in support of a national history of science for Wales, this article explores the legacy of Richard Price and his considerable contribution to science and the intellectual history of Wales. -

Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches Within the New Digital History (Pp

CHAPTER 14 The Many Ways to Talk about the Transits of Venus Astronomical Discourses in Philosophical Transactions, 1753–1777 Reetta Sippola A Popular Astronomical Event In the 1760s, one of astronomy’s rarest predictable phenomena, the so-called Transit of Venus, was calculated to take place twice: in 1761 and in 1769. This phenomenon, when the planet Venus passes across the Sun, from the Earth’s vantage point, was not only extremely rare, as the previous transit had taken place in 1639 and the next was to follow in 1874, but also very valuable scien- tifically, as observing this kind of transit would make it possible to determine the distance between the Earth and the Sun more accurately than before. This could in turn make it easier to improve a number of practical issues relying on astronomical knowledge, foremost among them to improve the accuracy of calculating locations at sea, which at this time was at best inaccurate, often resulting in costly and deadly accidents. Thus, the two Transit of Venus events and the astronomical information that could be derived from observing them enjoyed wide interest among both scientific professionals and the general How to cite this book chapter: Sippola, R. (2020). The many ways to talk about the Transits of Venus: Astronomical discourses in Philosophical Transactions, 1753–1777. In M. Fridlund, M. Oiva, & P. Paju (Eds.), Digital histories: Emergent approaches within the new digital history (pp. 237–257). Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. https://doi.org/10.33134 /HUP-5-14 238 Digital Histories public. The scientific interest in the transits during the 18th century was rep- resented through a large number of news items and scientific reports in the scientific literature, especially in scientific periodicals, such as thePhilosophi - cal Transactions of the Royal Society of London. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

The Meridian Arc Measurement in Peru 1735 – 1745

The Meridian Arc Measurement in Peru 1735 – 1745 Jim R. SMITH, United Kingdom Key words: Peru. Meridian. Arc. Triangulation. ABSTRACT: In the early 18th century the earth was recognised as having some ellipsoidal shape rather than a true sphere. Experts differed as to whether the ellipsoid was flattened at the Poles or the Equator. The French Academy of Sciences decided to settle the argument once and for all by sending one expedition to Lapland- as near to the Pole as possible; and another to Peru- as near to the Equator as possible. The result supported the view held by Newton in England rather than that of the Cassinis in Paris. CONTACT Jim R. Smith, Secretary to International Institution for History of Surveying & Measurement 24 Woodbury Ave, Petersfield Hants GU32 2EE UNITED KINGDOM Tel. & fax + 44 1730 262 619 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ddl.org/figtree/hsm/index.htm HS4 Surveying and Mapping the Americas – In the Andes of South America 1/12 Jim R. Smith The Meridian Arc Measurement in Peru 1735-1745 FIG XXII International Congress Washington, D.C. USA, April 19-26 2002 THE MERIDIAN ARC MEASUREMENT IN PERU 1735 – 1745 Jim R SMITH, United Kingdom 1. BACKGROUND The story might be said to begin just after the mid 17th century when Jean Richer was sent to Cayenne, S. America, to carry out a range of scientific experiments that included the determination of the length of a seconds pendulum. He returned to Paris convinced that in Cayenne the pendulum needed to be 11 lines (2.8 mm) shorter there than in Paris to keep the same time. -

Telling Time By: Sophia James Education, LLC the World Is Fascinated by How “Time” Goes by Fast Or How We Never Have Enough

Telling Time By: Sophia James Education, LLC The world is fascinated by how “time” goes by fast or how we never have enough “time” in a day. For ages the concept of time have fascinated people. For thousand of years time was measured by observing the movement of the sun, moon, or stars. We have used sundials and also clocks for many years to measure time. In order to record or indicate time devices were created. The devices are clocks, watches, and sundials. The oldest of these three devices are the sundials or shadow clocks. Many years ago people used sundials to in- dicate time of the day by the position of the shadows of objects on which the rays of the sun falls on. Through- out the day the sun moves across the sky, causing the shadows of the objects to move. Clocks, are machines that performs regular movements in equal intervals of time and is linked to a counting mechanisms that records the number of movements. The word clock comes from the Greek hora (“time”) and logos (“telling”). All clocks, of whatever form, are made with the principle of regular movements and equal intervals. Sometimes it is important to measure time exactly, such as when conducting an experiment or baking or when setting an appointment. Sometimes accuracy is not so important example when we are on vacation and have no timed plans. It is believed that shadow clocks or sundials known as gnomon, were the first device for indicating time.This sundial consisted of one vertical stick or pillar; the shadow that it cast gave an indication of the time of the day. -

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective

The Venus Transit: a Historical Retrospective Larry McHenry The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? A: Kepler’s Prediction – 1627: B: 1st Transit Observation – Jeremiah Horrocks 1639 2) Why was it so Important? A: Edmund Halley’s call to action 1716 B: The Age of Reason (Enlightenment) and the start of the Industrial Revolution 3) The First World Wide effort – the Transit of 1761. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 4) The Second Try – the Transit of 1769. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 5) The 19th Century attempts – 1874 Transit A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 6) The 19th Century’s Last Try – 1882 Transit - Photography will save the day. A: Countries and Astronomers involved B: What happened on Transit Day C: The Results 7) The Modern Era A: Now it’s just for fun: The AU has been calculated by other means). B: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation C: My personal experience – 2004 D: the 2004 and 2012 Transits: a Global Observation…Cont. E: My personal experience - 2012 F: New Science from the Transit 8) Conclusion – What Next – 2117. Credits The Venus Transit: A Historical Retrospective 1) What is a ‘Venus Transit”? Introduction: Last June, 2012, for only the 7th time in recorded history, a rare celestial event was witnessed by millions around the world. This was the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the Sun. -

Philosophical Transactions (A)

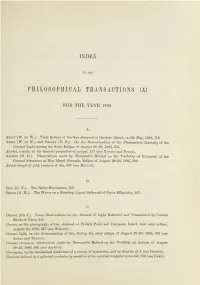

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1889. A. A bney (W. de W.). Total Eclipse of the San observed at Caroline Island, on 6th May, 1883, 119. A bney (W. de W.) and T horpe (T. E.). On the Determination of the Photometric Intensity of the Coronal Light during the Solar Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363. Alcohol, a study of the thermal properties of propyl, 137 (see R amsay and Y oung). Archer (R. H.). Observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of Extension of the Coronal Streamers at Hog Island, Grenada, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382. Atomic weight of gold, revision of the, 395 (see Mallet). B. B oys (C. V.). The Radio-Micrometer, 159. B ryan (G. H.). The Waves on a Rotating Liquid Spheroid of Finite Ellipticity, 187. C. Conroy (Sir J.). Some Observations on the Amount of Light Reflected and Transmitted by Certain 'Kinds of Glass, 245. Corona, on the photographs of the, obtained at Prickly Point and Carriacou Island, total solar eclipse, August 29, 1886, 347 (see W esley). Coronal light, on the determination of the, during the solar eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363 (see Abney and Thorpe). Coronal streamers, observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382 (see A rcher). Cosmogony, on the mechanical conditions of a swarm of meteorites, and on theories of, 1 (see Darwin). Currents induced in a spherical conductor by variation of an external magnetic potential, 513 (see Lamb). 520 INDEX. -

Lunar Distances Final

A (NOT SO) BRIEF HISTORY OF LUNAR DISTANCES: LUNAR LONGITUDE DETERMINATION AT SEA BEFORE THE CHRONOMETER Richard de Grijs Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, Balaclava Road, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract: Longitude determination at sea gained increasing commercial importance in the late Middle Ages, spawned by a commensurate increase in long-distance merchant shipping activity. Prior to the successful development of an accurate marine timepiece in the late-eighteenth century, marine navigators relied predominantly on the Moon for their time and longitude determinations. Lunar eclipses had been used for relative position determinations since Antiquity, but their rare occurrences precludes their routine use as reliable way markers. Measuring lunar distances, using the projected positions on the sky of the Moon and bright reference objects—the Sun or one or more bright stars—became the method of choice. It gained in profile and importance through the British Board of Longitude’s endorsement in 1765 of the establishment of a Nautical Almanac. Numerous ‘projectors’ jumped onto the bandwagon, leading to a proliferation of lunar ephemeris tables. Chronometers became both more affordable and more commonplace by the mid-nineteenth century, signaling the beginning of the end for the lunar distance method as a means to determine one’s longitude at sea. Keywords: lunar eclipses, lunar distance method, longitude determination, almanacs, ephemeris tables 1 THE MOON AS A RELIABLE GUIDE FOR NAVIGATION As European nations increasingly ventured beyond their home waters from the late Middle Ages onwards, developing the means to determine one’s position at sea, out of view of familiar shorelines, became an increasingly pressing problem.