Volume 55 Numbers 1 & 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of the United States

NO. 16-273 In the Supreme Court of the United States GLOUCESTER COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, Petitioner, v. G.G., BY HIS NEXT FRIEND AND MOTHER, DEIRDRE GRIMM, Respondent. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE 8,914 STUDENTS, PARENTS, GRANDPARENTS, AND COMMUNITY MEMBERS, ET AL., IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER Kristen K. Waggoner David A. Cortman Counsel of Record J. Matthew Sharp Gary S. McCaleb Rory T. Gray Alliance Defending Freedom Alliance Defending Freedom 15100 N. 90th Street 1000 Hurricane Shoals Rd. Scottsdale, AZ 85260 N.E., Ste. D-1100 [email protected] Lawrenceville, GA 30043 (480) 444-0020 (770) 339-0774 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ...................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................................. 2 ARGUMENT .................................................................. 3 I. Title IX Does Not Require Schools to Violate Bodily Privacy Rights By Allowing Students to Use Locker Rooms, Showers, and Restrooms of the Opposite Sex. .................................................. 5 II. Students’ Bodily Privacy Rights Bar the School Board From Opening Sex-Specific Locker Room, Shower, and Restroom Facilities to Members of the Opposite Sex. ........................ 12 III.Exposing Individuals to Members of the Opposite Sex in Places Where Personal Privacy is Expected is Forbidden by the Constitutional Right of Bodily Privacy. ............. 14 IV. Bodily Privacy Rights Preclude Opening Even Certain Sex-Specific Places of Public Accommodation to Members of the Opposite Sex. ...................................................................... 18 V. Even in the Prison Context, the Constitutional Right of Bodily Privacy Forbids Regularly Exposing Unclothed Inmates to the View of Opposite-Sex Guards, and Students Have Much More Robust Privacy Rights. -

DOCUMENTING MIRACLES in the AGE of BEDE by THOMAS EDWARD ROCHESTER

SANCTITY AND AUTHORITY: DOCUMENTING MIRACLES IN THE AGE OF BEDE by THOMAS EDWARD ROCHESTER A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This doctoral dissertation investigates the writings of the Venerable Bede (673-735) in the context of miracles and the miraculous. It begins by exploring the patristic tradition through which he developed his own historical and hagiographical work, particularly the thought of Gregory the Great in the context of doubt and Augustine of Hippo regarding history and truth. It then suggests that Bede had a particular affinity for the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles as models for the writing of specifically ecclesiastical history. The use of sources to attest miracle narratives in six hagiographies known to Bede from Late Antiquity are explored before applying this knowledge to Bede and five of his early Insular contemporaries. The research is rounded off by a discussion of Bede’s use of miracles in the context of reform, particularly his desire to provide adequate pastoral care through his understanding of the ideal bishop best exemplified by Cuthbert and John of Beverley. -

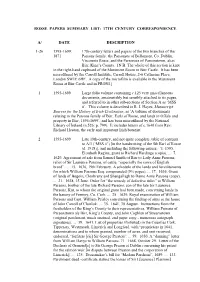

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbreviations are made according to the Council for British Archaeology’s Standard List of Abbreviated Titles of Current Series as at April 1991. Titles not covered in this list are abbreviated according to British Standard BS 4148:1985, with some minor exceptions. (———), 1793. Letter from ‘Mr W. T.’, Gentleman’s Mag., (———), 1933. ‘Proceedings ... 8 May 1933’, Trans. Bristol LXIII, 791 Gloucestershire Archaeol. Soc., LV, 1–12 (———), 1846a. ‘Proceedings ... 9 April 1845’, J. Brit. (———), 1935. ‘Carved stone in South Cerney church, Archaeol. Ass., ser. 1, I, 63–7 Gloucestershire’, Antiq. J., XV, 203–4 (———), 1846b. ‘Proceedings ... 13 August 1845’, J. Brit. (———), 1936. ‘Proceedings ... 20 May 1936’, Trans. Bristol Archaeol. Ass., ser. 1, I, 247–57 Gloucestershire Archaeol. Soc., LVIII, 1–7 (———), 1876. ‘S. Andrew’s church, Aston Blank, (———), 1949. ‘Roman Britain in 1948’, J. Roman Stud., Gloucestershire’, Church Builder, LIX, 172–4 XXXIX, 96–115 (———), 1886. ‘Diddlebury’, Trans. Shropshire Archaeol. (———), 1958–60. ‘A ninth century tombstone from Natur. Hist. Soc., IX, 289–304 Clodock’, Trans. Woolhope Natur. Fld. Club, XXXVI, (———), 1887. ‘Temple Guiting Church’, Gloucestershire 239 Notes and Queries, III, 204–5 (———), 2000. ‘Reports: West Midlands archaeology in (———), 1889. Report of the reopening of Wyre Piddle 2000’, West Midlands Archaeol., XLIII, 54–132 church, The Evesham Journal and Four Shires Advertiser, 31 (———), 2004. ‘Mystery of the disappearing font’, Gloss- August 1889, 8 ary: the joint newsletter of the Gloucestershire Record Office and (———), 1893–4a. ‘Discovery of mediæval and Roman the Friends of Gloucestershire Archives (Spring 2004), 4 remains on the site of the Tolsey at Gloucester’, Illus. Archaeol., I, 259–63 Abrams, L., 1996. -

Index of Moneyers Represented in the Catalogue

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-26016-9 — Medieval European Coinage Edited by Rory Naismith Index More Information INDEX OF MONEYERS REPRESENTED IN THE CATALOGUE Ordinary type indicates pages, bold type catalogue entries. Abba (Chester) 1474 , (Mercia) 1300 Ælfwine (Bristol) 1984 , (Cambridge) 1820 , (Chester) Abenel 2355 , 2456 , 2487 1479 , (Chichester) 2291 , 2322 , (Cricklade) 2110 , Aculf (east midlands) 1667 (Huntingdon) 2138 , (London) 1937 , 1966 , 2140 , Adalaver (east midlands) 1668 – 9 (Maldon) 1855 – 6 , (Thetford) 2268 , (Wilton) 2125 , 2160 , Adalbert 2457 – 9 , (east midlands) 1305 – 6 2179 Ade (Cambridge) 1947 , 1986 Æscman (east midlands) 1606 , 1670 , (Stamford) 1766 Adma (Cambridge) 1987 Æscwulf (York) 1697 Adrad 2460 Æthe… (London) 1125 Æ… (Chester) 1996 Æthel… (Winchester) 1922 Ælf erth 1511 , 1581 Æthelferth 1560 , (Bath) 1714 , (Canterbury) 1451 , (Norwich) Ælfgar (London) 1842 2051 , (York) 1487 , 2605 ; 303 Ælfgeat (London) 1843 Æthelgar 1643 , (Winchester) 1921 Ælfheah (Stamford) 2103 Æthelhelm (East Anglia) 940 , (Northumbria) 833 , 880 – 6 Ælfhere (Canterbury) 1228 – 9 Æthelhere (Rochester) 1215 Ælfhun (London) 1069 Æthellaf (London) 1126 , 1449 , 1460 Ælfmær (Oxford) 1913 Æthelmær (Lincoln) 2003 Ælfnoth (London) 1755 , 1809 , 1844 Æthelmod (Canterbury) 955 Ælfræd (east midlands) 1556 , 1660 , (London) 2119 , (Mercia/ Æthelnoth 1561 – 2 , (Canterbury) 1211 , (east midlands) 1445 , Wessex) 1416 , ( niweport ) (Lincoln) 1898 , 1962 Ælfric (Barnstaple) 2206 , (Cambridge) 1816 – 19 , 1875 – 7 , Æthelræd 90 -

Derbyshire Parish Registers. Marriages

Gc 942.51019 Aalp V. 5 942.51019 '^. L. Aalp V.5 1379093 I QENEALOSV C=0U1.e:cT10N / ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBBAR| 3 1833 00727 4258 DERBYSHIRE I PARISH REGISTERS. V. HILLIMORES AKISH REGISTER SERIES. '01.. CII. (DERBYSHIRE, VOL. V.) One hundred and fifty only printed. ue.^. Derbyshire Parish Registers Edited by W. P. W. PHILLIMORE, M.A., B.C.L. AND LL. LL. SIMPSON. VOL. V. QrX. aoniion : Issued to the Subscribers by Phillimore & Co. 124, Chancery Lane. 1909. — PREFACE. As promised in the last volume of the Marriage Registers of Derbyshire, the marriage records of St. Michael's are printed in this volume. ^ '^^QOQ^ The Editors do not doubt that these will prove equally interesting to Derbyshire people. In Volume V. they hope to print further instalments of town registers in the shape of those of St. Peter's, and also some village registers, to be followed in next volume by St. Werburgh's. It will be convenient to give here a list of the Derby- shire parishes of which the Registers have been printed in this series : — verbatim. They are reduced to a common form, and the following contractions have been freely used : w. = widower or widow. p. = of the parish of. s. = spinster, single woman, or co. = in the county of. son of. b. = bachelor or single man. dioc. = in the diocese of. d. = daughter of lie. = marriage licence. All these extracts have been made by Mr. LI. LI. Simpson. Thanks are due to the parish clergy for permission to print these extracts. It may be well to remind the reader that these printed abstracts of the registers are not legal "evidence." For certificates application must be made to the local clergy. -

HADLEIGH DEANERY and ITS COURT. There Were in the County

16 HADLEIGH DEANERY AND ITS COURT. There were in the County of Suffolka few parishes which lay without the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Norwich,and wereconsequently known as " Pectliars." These parishes were Hadleigh, Monks' Eleigh, and Moulton, which were in the jurisdiction of the Arch- bishop of Canterbury, and Freckenham in the juris- diction of the Bishop of Rochester. In the last volume of the Proceedings of our Institute (p. 325) it was shewn that the South Elmham parishes con- stituted a Deanery because they formed a part of the temporalities of the Bishop of Norwich ; so, likewise, as the three parishes of Hadleigh, Monks' Eleigh and Moulton :weremanors belonging to the Archbishop of Canterbury they possessed a Court, and the official of the Manors was the Commissary for the Deanery to which these said parishes belonged. This Deanery was known as the Deanery of Bocking, a town now considered as part of Braintree, in Essex. Six parishes in the county of Essex comprised the remaining part of the Deanery, which did not acknowledge the in- hibition of either the Bishop of Norwich or the Bishop of London. It was nearly a century previous to the Constitu- tion.of Ecclesiastical Courts by William I. that Brith- noth, the Earl who fell at the battle of Maldon, 991, gave the manors of Hadleigh and Illeigh to the Prior of Christ Church, Canterbury, and the Convent of the same place to be held in free, pure, and perpetual alms. When the Ecclesiastical Court of the Deanery was established it is probable that the Rector of Bock- ing was appointed presiding judge. -

Autumn 07 Cover

Spink Coins 21050 Abramson II cover.qxp_Layout 1 23/02/2021 12:36 Page 1 £25 THE TONY ABRAMSON COLLECTION OF DARK AGE COINAGE - PART II 271 THE TONY ABRAMSON COLLECTION OF DARK AGE COINAGE - PART II: NORTHUMBRIA NORTHUMBRIA 18 MARCH 2021 STAMPS COINS BANKNOTES MEDALS BONDS & SHARES AUTOGRAPHS BOOKS WINE & SPIRITS HANDBAGS COLLECTIONS ADVISORY SERVICES SPECIAL COMMISSIONS LONDON 18 MARCH 2021 69 Southampton Row, Bloomsbury, London WC1B 4ET www.spink.com © Copyright 2021 LONDON Spink Coins 21050 Abramson II cover.qxp_Layout 1 23/02/2021 12:37 Page 2 337 335 336 397 405 408 338 342 419 343 416 424 348 363 429 430 364 432 371 436 376 378 439 447 387 396 478 382 452 463 Spink Coins 21050 Abramson II pages.qxp_Layout 1 23/02/2021 14:54 Page 1 THE TONY ABRAMSON COLLECTION OF DARK AGE COINAGE - PART II NORTHUMBRIA 69 Southampton Row, Bloomsbury London WC1B 4ET tel +44 (0)20 7563 4000 fax +44 (0)20 7563 4066 Vat No: GB 791627108 Sale Details | Thursday 18 March 2021 at 3.00 p.m. | When sending commission bids or making enquiries, this sale should be referred to as ABRAMSON2 - 21050 Viewing of Lots | At Spink London Private viewing by appointment only (subject to government guidelines) Live platform | Your Specialists for this Sale Bids Payment Enquiries Axel Kendrick Veronica Morris Dora Szigeti [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0)20 7563 4018 +44 (0)20 7563 4108/4005 fax +44 (0)20 7563 4037 Gregory Edmund Henrik Berndt [email protected] [email protected] Technical Issues VAT Enquiries +44 (0)20 7563 4048 +44 (0)20 7563 4064 [email protected] John Winchcombe +44 (0)20 7563 4089 [email protected] +44 (0)20 7563 4101 The Spink Environment Commitment: Paper from Sustainable Forests and Clean Ink Spink has a long history of preserving not only collectables but our planet, too. -

BRIDGE....Centenary Special Edition - July 2005 It Was Southwark Diocese’S 100Th Birthday on the Weekend of 2 and 3 July 2005

TheBRIDGE....Centenary Special Edition - July 2005 It was Southwark Diocese’s 100th birthday on the weekend of 2 and 3 July 2005. The events in Lambeth Palace Gardens on Saturday and at the Cathedral and in its grounds on Sunday were a wonderful celebration of all that Southwark has been and is. In this commemorative edition of the Bridge we’ll try to give you a flavour of the Diocese and its history and the celerations to mark the centenary. A Century of People, Places and Prayer The the ‘Bishops Appeal for 6th Bishop of becoming Bishop of 9th Bishop of Clergy Stipends’ raising Newcastle for eight years, 9th Bishop of The Area Diocesan £70,000 in five years to Southwark returning to Southwark as Southwark ensure that clergy were paid Bishop in 1980. During his Bishops Bishops adequate stipends. He also episcopate (in 1985) the parts raised £100,000 so that 25 of Croydon in Canterbury …today There have been just nine churches could be built to Diocese joined Southwark. Bishops in the hundred years mark the 25th year of the Bishop Ronnie developed the The Bishop of Croydon - since the Diocese of Diocese and enhanced the suffragan system giving the Rt Rev Nick Baines - Southwark began. Each Cathedral. He was the only greater autonomy to the came to Southwark Diocese contributed to the Bishop of Southwark to Bishops of Croydon, in February 2000 as establishment and become an Archbishop (York Kingston and Woolwich. He Archdeacon of Lambeth, development of our 1942-55). was the chairman of the having previously been Vicar Diocese…. -

Wednesday 25Th April 2018, 13:00

£25 www.dnw.co.uk THE NORTH YORKSHIRE MOORS COLLECTION OF BRITISH COINS DIX 16 Bolton Street Mayfair FORMED BY MARVIN LESSEN London W1J 8BQ England PART 1 NOONAN Telephone 020 7016 1700 Fax 020 7016 1799 Wednesday 25th April 2018, 13:00 WEBB Email [email protected] Catalogue 146 BOARD of DIRECTORS Pierce Noonan Managing Director and CEO 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Nimrod Dix Executive Chairman 020 7016 1820 [email protected] Robin Greville Head of Systems Technology 020 7016 1750 [email protected] Christopher Webb Head of Coin Department 020 7016 1801 [email protected] AUCTION SERVICES and CLIENT LIAISON Philippa Healy Head of Administration (Associate Director) 020 7016 1775 [email protected] Emma Oxley Accounts and Viewing 020 7016 1701 [email protected] Christopher Mellor-Hill Head of Client Liaison (Associate Director) 020 7016 1771 [email protected] Chris Finch Hatton Client Liaison 020 7016 1754 [email protected] David Farrell Head of Logistics 020 7016 1753 [email protected] James King Deputy Head of Logistics 020 7016 1833 [email protected] COINS, BANKNOTES, TOKENS and COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Christopher Webb Head of Department (Director) 020 7016 1801 [email protected] Peter Preston-Morley Specialist (Associate Director) 020 7016 1802 [email protected] Jim Brown Specialist 020 7016 1803 [email protected] Tim Wilkes Specialist 020 7016 1804 [email protected] Nigel Mills Consultant (Artefacts and Antiquities) 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Peter Mitchell Consultant (British Hammered Coins) 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Michael O’Grady Consultant -

Tyndale Society Journal

The Tyndale Society Journal No. 42 Summer 2013 About the Tyndale Society Registered UK Charity Number 1020405 Founded by Professor David Daniell in 1995, five hundred and one years after Tyndale’s birth. The Society’s aim is to spread knowledge of William Tyndale’s work and influence, and to pursue study of the man who gave us our English Bible. Membership Benefits • 2 issues of the Tyndale Society Journal a year • Many social events, lectures and conferences • Exclusive behind-the-scenes historical tours • Access to a worldwide community of experts • 50% discount on Reformation. • 25% advertising discount in the Journal For further information visit: www.tyndale.org or see inside the back cover of this edition of the Tyndale Society Journal. Trustees Mary Clow; Dr Paul Coones; Charlotte Dewhurst; Rochelle Givoni; David Green; Revd David Ireson; Dr Guido Latré; Revd Dr Simon Oliver; Dr Barry T. Ryan; Jennifer Sheldon. Patrons His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury; Rt. Rev. and Rt. Hon. Lord Carey of Clifton; Baroness James of Holland Park; Lord Neill of Bladen QC; Prof. Sir Christopher Zeeman, former Principal, Hertford College, Oxford; Mr David Zeidberg. Advisory Board Sir Anthony Kenny; Anthony Smith, Emeritus President, Magdalen College; Penelope Lively; Philip Howard; Anne O’Donnell, Catholic University of America; Professor John Day, St Olaf ’s College, Minnesota; Professor Peter Auksi, University of W. Ontario; Dr David Norton, Victoria University, Wellington; Gillian Graham, Emeritus Hon. Secretary. Other Tyndale Society Publications Reformation Editor: Dr Hannibal Hamlin Humanities, English & Religious Studies, The Ohio State University, 164 West 17th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210-1370, USA. -

2014 Annual Report

Spring 2015 2014 Annual Report Message from the President Dear Friends, As we reach the end of another successful academic year, we are thankful for the blessings we have been granted. In May, we will send another group of 100 Purpose Road students into the world equipped with good character, Pippa Passes, Kentucky 41844 work experience, knowledge, and a diploma. We hope that you will join us in praying that the Lord blesses Pippa’s Song is published for them and guides them through the decisions to come. friends, alumni, and students of Alice Lloyd College. Third class If you drive through campus you will not only hear postage is paid at Pippa Passes, the typical buzz of student life, but also the sound of Kentucky. power tools and heavy machinery. The construction of the Bettinger Center for Servant Leadership is well Pippa's Song underway. This building is located in the center of our Spring 2015 beautiful campus and will house our student work Vol. LXIV No. 1 program and campus outreach activities. We also plan to give a facelift to many of our other buildings Institutional Advancement Office throughout the course of the summer. We have an exciting project that we hope to of Alice Lloyd College 100 Purpose Road inform you of soon. You can stay up to date on that by looking on our website and social Pippa Passes, Kentucky 41844 media profiles until our summer edition of Pippa’s Song is released. 606-368-6055 • www.alc.edu Alice Geddes Lloyd was truly a selfless servant and her life’s work continues to be an Joe Alan Stepp inspiration to Appalachian youth.