Belarus by Vitali Silitski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testimony :: Stephen Nix

Testimony :: Stephen Nix Regional Program Director, Eurasia - International Republican Institute Mr. Chairman, I wish to thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Commission today. We are on the eve of a presidential election in Belarus which holds vital importance for the people of Belarus. The government of the Republic of Belarus has the inherit mandate to hold elections which will ultimately voice the will of its people. Sadly, the government of Belarus has a track record of denying this responsibility to its people, its constitution, and the international community. Today, the citizens of Belarus are facing a nominal election in which their inherit right to choose their future will not be granted. The future of democracy in Belarus is of strategic importance; not only to its people, but to the success of the longevity of democracy in all the former Soviet republics. As we have witnessed in Georgia and Ukraine, it is inevitable that the time will come when the people stand up and demand their rightful place among their fellow citizens of democratic nations. How many more people must be imprisoned or fined or crushed before this time comes in Belarus? Mr. Chairman, the situation in Belarus is dire, but the beacon of hope in Belarus is shining. In the midst of repeated human rights violations and continual repression of freedoms, a coalition of pro-democratic activists has emerged and united to offer a voice for the oppressed. The courage, unselfishness and determination of this coalition are truly admirable. It is vitally important that the United States and Europe remain committed to their support of this democratic coalition; not only in the run up to the election, but post-election as well. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Review-Chronicle of Human Violations in Belarus in 2009

The Human Rights Center Viasna Review-Chronicle of Human Violations in Belarus in 2009 Minsk 2010 Contents A year of disappointed hopes ................................................................7 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in January 2009....................................................................9 Freedom to peaceful assemblies .................................................................................10 Activities of security services .....................................................................................11 Freedom of association ...............................................................................................12 Freedom of information ..............................................................................................13 Harassment of civil and political activists ..................................................................14 Politically motivated criminal cases ...........................................................................14 Freedom of conscience ...............................................................................................15 Prisoners’ rights ..........................................................................................................16 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in February 2009................................................................17 Politically motivated criminal cases ...........................................................................19 Harassment of -

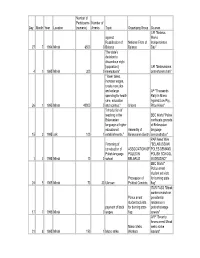

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Evolution of the Belarusian National Movement in The

EVOLUTION OF THE BELARUSIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PAGES OF PERIODICALS (1914-1917) By Aliaksandr Bystryk Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Maria Kovacs Secondary advisor: Professor Alexei Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract Belarusian national movement is usually characterised by its relative weakness delayed emergence and development. Being the weakest movement in the region, before the WWI, the activists of this movement mostly engaged in cultural and educational activities. However at the end of First World War Belarusian national elite actively engaged in political struggles happening in the territories of Western frontier of the Russian empire. Thus the aim of the thesis is to explain how the events and processes caused by WWI influenced the national movement. In order to accomplish this goal this thesis provides discourse and content analysis of three editions published by the Belarusian national activists: Nasha Niva (Our Field), Biełarus (The Belarusian) and Homan (The Clamour). The main findings of this paper suggest that the anticipation of dramatic social and political changes brought by the war urged national elite to foster national mobilisation through development of various organisations and structures directed to improve social cohesion within Belarusian population. Another important effect of the war was that a part of Belarusian national elite formulated certain ideas and narratives influenced by conditions of Ober-Ost which later became an integral part of Belarusian national ideology. CEU eTD Collection i Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1. Between krajowość and West-Russianism: The Development of the Belarusian National Movement Prior to WWI ..................................................................................................... -

General Conclusions and Basic Tendencies 1. System of Human Rights Violations

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND BASIC TENDENCIES 1. SYSTEM OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS The year 2003 was marked by deterioration of the human rights situation in Belarus. While the general human rights situation in the country did not improve, in its certain spheres it significantly changed for the worse. Disrespect for and regular violations of the basic constitutional civic rights became an unavoidable and permanent factor of the Belarusian reality. In 2003 the Belarusian authorities did not even hide their intention to maximally limit the freedom of speech, freedom of association, religious freedom, and human rights in general. These intentions of the ruling regime were declared publicly. It was a conscious and open choice of the state bodies constituting one of the strategic elements of their policy. This political process became most visible in formation and forced intrusion of state ideology upon the citizens. Even leaving aside the question of the ideology contents, the very existence of an ideology, compulsory for all citizens of the country, imposed through propaganda media and educational establishments, and fraught with punitive sanctions for any deviation from it, is a phenomenon, incompatible with the fundamental human right to have a personal opinion. Thus, the state policy of the ruling government aims to create ideological grounds for consistent undermining of civic freedoms in Belarus. The new ideology is introduced despite the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus which puts a direct ban on that. -

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus

Truth Stumbles in the Street Christian Democratic Activism in Belarus Geraldine Fagan Abstract: Few are aware that prominent figures in the Belarusian opposition movement are motivated by Christian conviction. In this article, the author trac- es how President Alexander Lukashenko’s restriction of religious freedom has prompted Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants to turn toward democratic activ- ism; it also discusses their rediscovery of religious freedom as a long-standing core value of Belarusian identity. The author’s findings draw on interviews con- ducted in Minsk in the aftermath of the December 2010 presidential election, including those with Christian opposition activists who were subsequently jailed. Keywords: Belarus, democracy, freedom, religion nce a dictatorial regime has muzzled civil society’s more cantankerous O elements—rival political parties and the independent media—a stage is reached at which faith groups, even if falteringly, join the vanguard in the struggle for freedom and justice. In 1980s Communist Poland, the Catholic Church offered a vital moral platform for mass dissent by the Solidarity movement. Prayer meetings at a Leipzig Lutheran church formed the nucleus of protest by hundreds of thousands of East Germans in the weeks before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Might faith-inspired opposition similarly prove a catalyst for political change in Belarus, dubbed “the last true dictatorship in the center of Europe” by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2005?1 The prospects Geraldine Fagan is a 2010–2011 Joseph R. Crapa Fellow at the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. She has monitored religious freedom in Belarus since 2003 as the Moscow correspondent for Forum 18 News Service. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Belarus: a Chinese Solution?1 Tomasz Kamusella University of St

Belarus: A Chinese Solution?1 Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews Bezviz, or the European Union’s visa waver program extended to Ukraine a year ago in June 2017,2 must have angered the autocratic regimes in neighboring Belarus and Russia. Why would Ukrainians, who had just lost Crimea and were unable to stop the Russian incursion in the east of their country, be allowed to enjoy Rome or Paris without having to face the indignity of applying for a Schengen visa? The Eiffel Tower, the Sistine Chapel, or the Canaries can hardly be successfully replaced with the likes of Sochi, the rebuilt Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow, or the Crimean seacoast stricken by the dearth of water. Neither are the Kuril Islands, known for their balmy climate conducive to all-year-round holidaying. To the average Belarusian and Russian the west inexplicably rewarded Ukraine for the military losses suffered with the privilege that should first be accorded to Russians or Belarusians. Autocracies as good at winning elections with the help of political technologists and sophisticated IT systems as those in Belarus and Russia are nevertheless still susceptible to fickle popularity felt by the ‘electorates’ for the strongman at the top. The less a dictator is popular, the more direct violence has to be applied to wage power. In turn, unleashing too much violence causes popularity to plummet even further. This confronts the regime with the unwanted downward spiral of increasing state violence that simultaneously generates instability, which in no time may morph into effective political opposition. And such opposition stands a chance of unsettling the dictator from power; an option best to be avoided. -

The Baltic Sea Region the Baltic Sea

TTHEHE BBALALTTICIC SSEAEA RREGIONEGION Cultures,Cultures, Politics,Politics, SocietiesSocieties EditorEditor WitoldWitold MaciejewskiMaciejewski A Baltic University Publication Baltic and East Slavic languages; 17 Yiddish Sven Gustavsson 1. Language policies in the Russian Empire In the middle of the 17th century, when the Russian Empire had recovered from political unrest, it directed its expansionist efforts towards the west and southwest, towards the Swedish and the Polish-Lithuanian states. This expansion was completed with the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The situation only changed with the revolution in 1917 and the end of World War I. Then Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland became independent states. Poland also won back parts of its former possessions in Belarus and Ukraine. With World War II, the Soviet Union restored many of the former borders of the Russian empire, recapturing Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Polish parts of Ukraine and Belarus and also incorporating most of Eastern Prussia. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 following the August coup reduced the empire’s area once again. Clearly, the history and the language policy of the Russian empire has had a great impact on the history of many of the languages and peoples in the Baltic area. A short overview is therefore appropriate here. Russification has been a part of Russian policy from the begin- ning. After Mazepa’s cooperation with the Swedish king Charles XII, all traces of Ukrainian autonomy promised in the Treaty of Perejaslavl of 1654 vanished. In 1720, even the printing of Ukrainian works was forbidden. In the Estonian and Latvian areas taken from Sweden in the Great Nordic War at the beginning of the 18th century, the Tsar, however, relied on the mostly German nobility who got extensive privileges. -

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich SAIS Review of International Affairs, Volume 40, Number 2, Summer-Fall 2020, pp. 97-110 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/783885 [ Access provided at 7 Mar 2021 23:30 GMT from University Of South Florida Libraries ] National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to ‘Nation’ Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich This article examines the formation of nationalism in Belarus through two dimensions: elite ideology and everyday practice. I argue the presidential election of 2020 turned into a fundamental institutional crisis when a homogeneous set of ‘nation’ practices against the state ideology replaced existing elite ideology. This resulted in popular incremental changes in conceptions of national understanding. After twenty-six consecutive years in power, President Lukashenka unintentionally unleashed a process of national awakening leading to the rise of a new sovereign nation that demands the right to determine its own future, independent of geopolitical pressures and interference. Introduction ugust 2020 witnessed a resurgence of nationalist discourse in Belarus. AUnlike in the Transatlantic world, where politicians articulate visions of their nations under siege—by immigrants, refugees, domestic minority popu- lations—narratives of national and political failure dominate in Belarus Unlike trends in the Transatlantic resonate with large segments of the voting public. -

Culture and Change in Belarus

East European Reflection Group (EE RG) Identifying Cultural Actors of Change in Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova Culture and Change in Belarus Report prepared by Yael Ohana, Rapporteur Generale Bratislava, August 2007 Culture and Change in Belarus “Life begins for the counter-culture in Belarus after regime change”. Anonymous, at the consultation meeting in Kiev, Ukraine, June 14 2007. Introduction1 Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine have recently become direct neighbours of the European Union. Both Moldova and Ukraine have also become closer partners of the European Union through the European Neighbourhood Policy. Neighbourhood usually refers to people next-door, people we know, or could easily get to know. It implies interest, curiosity and solidarity in the other living close by. For the moment, the European Union’s “neighbourhood” is something of an abstract notion, lacking in substance. In order to avoid ending up “lost in translation”, it is necessary to question and some of the basic premises on which cultural and other forms of European cooperation are posited. In an effort to create constructive dialogue with this little known neighbourhood, the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) and the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) are currently preparing a three- year partnership to support cultural agents of change in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine. In the broad sense, this programme is to work with, and provide assistance to, initiatives and institutions that employ creative, artistic and cultural means to contribute to the process of constructive change in each of the three countries. ECF and GMF have begun a process of reflection in order to understand the extent to which the culture sphere in each of the three countries under consideration can support change, defined here as processes and dynamics contributing to democratisation, Europeanisation and modernisation in the three countries concerned.