The Use of Statistics and Facts in Contemporary Political Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Impact Investment Forum: Outputs and Agreed Actions

G8 Social Impact Investment Forum: Outputs and Agreed Actions G8 Social Impact Investment Forum Agenda Bloomberg, City Gate House, 39-45 Finsbury Square, London EC2A 1PQ Time Programme 0830 – 0855 Registration 0855 – 0900 Welcome 0900 – 0920 Opening Remarks (available online here) David Cameron, Prime Minister 0920 – 0930 Keynote Address (available online here) George Soros, Soros Fund Management and the Open Society Foundations 0930 – 1015 Social Impact Economy: Impact investors and social entrepreneurs (available online here) Tim Harford (Financial Times) interviews impact investors and social entrepreneurs including: • Matt Bannick (Omidyar Network) and Donn Tice (d.light) • Johannes Weber (Social Venture Fund) and Dirk Müller-Remus (auticon) • Michele Giddens (Bridges Ventures) and Dai Powell (HCT Group) 1015 – 1030 Break 1030 – 1040 Keynote Address (available online here) The Rt Hon Iain Duncan Smith MP, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, UK 1040 – 1210 Session One: Demonstrating the role of the social impact economy (available online here) Matthew Bishop (The Economist); Professor Mario Calderini (Politecnico di Torino); Minister Benoît Hamon (Minister Delegate with responsibility for the Social and Cooperative Economy and Consumer Affairs, France); Peter Holbrook (Social Enterprise UK); Karen Mills (Small Business Administration); and Nick O’Donohoe (Big Society Capital) 1210 – 1300 Lunch 1300 – 1330 Breakout sessions: Innovations in the social impact investment market • Innovation in public service delivery: Social impact -

The Big Society

House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee The Big Society Seventeenth Report of Session 2010–12 Volume II Oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume III, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/treascom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 7 December 2011 HC 902-II [Incorporating HC 716] Published on 14 December 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £13.00 The Public Administration Select Committee The Public Administration Select Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the reports of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration and the Health Service Commissioner for England, which are laid before this House, and matters in connection therewith, and to consider matters relating to the quality and standards of administration provided by civil service departments, and other matters relating to the civil service. Current membership Mr Bernard Jenkin MP (Conservative, Harwich and North Essex) (Chair) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan) Michael Dugher MP (Labour, Barnsley East) Charlie Elphicke MP (Conservative, Dover) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Robert Halfon MP (Conservative, Harlow) David Heyes MP (Labour, Ashton under Lyne) Kelvin Hopkins MP (Labour, Luton North) Greg Mulholland MP (Liberal Democrat, Leeds North West) Priti Patel MP (Conservative, Witham) Lindsay Roy MP (Labour, Glenrothes) The following members were also members of the Committee during the inquiry: Nick de Bois MP (Conservative, Enfield North) Mr Charles Walker MP (Conservative, Broxbourne) Powers The powers of the Committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 146. -

Unity, Vision and Brexit

1 ‘Brexit means Brexit’: Theresa May and post-referendum British politics Nicholas Allen Department of Politics and International Relations Royal Holloway, University of London Surrey, TW20 0EX [email protected] Abstract: Theresa May became prime minister in July 2016 as a direct result of the Brexit referendum. This article examines her political inheritance and leadership in the immediate wake of the vote. It analyses the factors that led to her victory in the ensuing Tory leadership contest and explores both the main challenges that confronted her and the main features of her response to them. During his first nine months in office, May gave effect to the referendum, defined Brexit as entailing Britain’s removal from membership of the European Union’s single market and customs union and sought to reposition her party. However, her failure to secure a majority in the 2017 general election gravely weakened her authority and the viability of her plans. At time of writing, it is unclear how much longer her premiership can last or if she will be able to exercise effective leadership over Brexit. Keywords: Theresa May; Brexit; prime ministers; leadership; Conservative party This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in British Politics. The definitive publisher-authenticated version, Nicholas Allen (2017) ‘‘Brexit means Brexit’: Theresa May and post-referendum British politics’, British Politics, First Online: 30 November, doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0067-3 is available online at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41293-017-0067-3 2 Introduction According to an old university friend, Theresa May had once wanted to be Britain’s first female prime minister (Weaver, 2016). -

Westminster Hall PDF File 0.05 MB

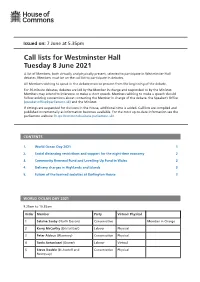

Issued on: 7 June at 5.35pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 8 June 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to participate in Westminster Hall debates. Members must be on the call list to participate in debates. All Members wishing to speak in the debate must be present from the beginning of the debate. For 30-minute debates, debates are led by the Member in charge and responded to by the Minister. Members may attend to intervene or make a short speech. Members wishing to make a speech should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office ([email protected]) and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. World Ocean Day 2021 1 2. Social distancing restrictions and support for the night-time economy 2 3. Community Renewal Fund and Levelling Up Fund in Wales 2 4. Delivery charges in Highlands and Islands 3 5. Future of the learned societies at Burlington House 3 WORLD OCEAN DAY 2021 9.25am to 10.55am Order Member Party Virtual/ Physical 1 Selaine Saxby (North Devon) Conservative Member in Charge 2 Kerry McCarthy (Bristol East) Labour Physical 3 Peter Aldous (Waveney) Conservative Physical 4 Tonia Antoniazzi (Gower) Labour Virtual 5 Steve Double (St Austell and Conservative Physical Newquay) -

Contents Theresa May - the Prime Minister

Contents Theresa May - The Prime Minister .......................................................................................................... 5 Nancy Astor - The first female Member of Parliament to take her seat ................................................ 6 Anne Jenkin - Co-founder Women 2 Win ............................................................................................... 7 Margaret Thatcher – Britain’s first woman Prime Minister .................................................................... 8 Penny Mordaunt – First woman Minister of State for the Armed Forces at the Ministry of Defence ... 9 Lucy Baldwin - Midwifery and safer birth campaigner ......................................................................... 10 Hazel Byford – Conservative Women’s Organisation Chairman 1990 - 1993....................................... 11 Emmeline Pankhurst – Leader of the British Suffragette Movement .................................................. 12 Andrea Leadsom – Leader of House of Commons ................................................................................ 13 Florence Horsbrugh - First woman to move the Address in reply to the King's Speech ...................... 14 Helen Whately – Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party ............................................................. 15 Gillian Shephard – Chairman of the Association of Conservative Peers ............................................... 16 Dorothy Brant – Suffragette who brought women into Conservative Associations ........................... -

Resources/Contacts for Older People's Action Groups on Housing And

Resources/contacts for Older People’s Action Groups on housing and ageing for the next General Election It is not long before the next general election. Politicians, policy makers and others are developing their manifestos for the next election and beyond. The Older People’s Housing Champion’s network (http://housingactionblog.wordpress.com/) has been developing its own manifesto on housing and will be looking at how to influence the agenda locally and nationally in the months ahead. Its manifesto is at http://housingactionblog.wordpress.com/2014/08/07/our-manifesto-for-housing-safe-warm-decent-homes-for-older-people/ To help Older People’s Action Groups, Care & Repair England has produced this contact list of key people to influence in the run up to the next election. We have also included some ideas of the sort of questions you might like to ask politicians and policy makers when it comes to housing. While each party is still writing their manifesto in anticipation of the Party Conference season in the autumn, there are opportunities to contribute on-line at the party websites included. National Contacts – Politicians, Parties and Policy websites Name Constituency Email/Website Twitter www.conservatives.com/ Conservative Party @conservatives www.conservativepolicyforum.com/1 [email protected] Leader Rt Hon David Cameron MP Witney, Oxfordshire @David_Cameron www.davidcameron.com/ Secretary of State for Brentwood and Ongar, [email protected] Communities and Local Rt Hon Eric Pickles MP @EricPickles Essex www.ericpickles.com -

Catholic Social Teaching: Sharing the Secret…

Catholic Social Teaching: Sharing the Secret… 1 September 2021 Volume 2, Number 9 In This Issue • Upcoming Events Tory MP Says ‘Some People Don't Need an Extra • Tory MP Says ‘Some People Don’t £20' Need An Extra £20’ No, he’s not talking about millionaires and billionaires, or even people who are in comfortable circumstances---Tory backbencher Andrew Rosindell has • Week of Action Sponsored by Stop argued that the extra £20 in Universal Credit brought in during the the Arms Fair coronavirus pandemic should be scrapped, saying “I think there are people • Forgiving Reality and Forgiving that quite like getting the extra £20 but maybe they don't need it.” Ourselves In contrast, Labour’s Carolyn Harris hit back, saying the £20 would be taken • Love, Justice and the Common Good away from “people who can least afford to lose it”. She added: “£20 is food • The Poor Evangelise Us for a week. £20 is a lifeline for people on Universal Credit.” Other Conservative party members also urged Chancellor Rishi Sunak to make the increase permanent. Former Tory leader and instigator of UPCOMING EVENTS Universal Credit Sir Iain Duncan Smith, along with five of his successors – Stephen Crabb, Damian Green, David Gauke, Esther McVey and Amber 1 September: World Day of Prayer for Rudd – have written to Sunak in an effort to persuade him to stick with the Season of Creation £5 billion benefits investment. 2-8 September: Week of Action to Sir Ian warned that a failure to keep the £20 uplift in place permanently protest the DSEI Arms Fair (see would “damage living standards, health and opportunities” for those that accompanying article in this issue). -

Contacting Your MP a Guide for Quakers

Contacting your MP a guide for Quakers This is a resource for Quakers and other people campaigning for positive change. It will help you to decide on an approach, contact your MP if appropriate, and engage with them further when they respond. Contacting your MP Introduction This is a briefing on how to contact your Member of Parliament (MP). They could help you to raise awareness of a political issue or to change a policy or legislation. A total of 650 MPs are elected to the House of Commons. Each MP represents an area of the UK containing an average of 75,000 voters. Some MPs represent parts of densely populated urban areas, while others represent geographically large but sparsely populated rural constituencies. In Scotland and Wales, some powers are devolved to the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Parliament respectively. If you live in Scotland or Wales and your issue is related to a devolved matter, you may wish to write to your Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) or Member of the Senedd (MS). If your issue is purely local, your local councillors may have more influence. Find your national and local politicians at www.writetothem.com. Begin by considering your aims, audiences and channels. Use our Yes You write to your MP using our top tips Toolkit for Action You receive a negative response Do you want to You receive a write to your MP? positive response You arrange a meeting to discuss what they and You reply with counter- you could do next. To arguments and suggest a help you prepare, refer meeting to discuss No to the ‘What your MP can do’ section of this guide and explore Hope for the Future’s resources. -

EU Referendum 2016 V7

EU Referendum 2016 Three Scenarios for the Government An insights and analysis briefing from The Whitehouse Consultancy Issues-led communications 020 7463 0690 [email protected] whitehouseconsulting.co.uk The EU Referendum The EU referendum has generated an unparalleled level of political If we vote to leave, a new Prime Minister will likely emerge from among debate in the UK, the result of which is still too close to call. Although the 'Leave' campaigners. What is questionable is whether Mr Cameron we cannot make any certain predictions, this document draws upon will stay in position to deal with the immediate questions posed by Whitehouse’s political expertise and media analysis to suggest what Brexit: such as the timetable for withdrawal, or how trading and may happen to the Government’s composition in the event of: diplomatic relations will proceed. Will he remain at Number 10, perhaps • A strong vote to remain (by 8% or more); until a party conference in the autumn, or will there be more than one new beginning? • A weak vote in favour of remaining (by up to 8%); or • A vote to leave. “The result could create If the UK chooses to remain by a wide margin, the subsequent reshue will aord an opportunity to repair the Conservative Party after a a new political reality.” bruising campaign period. This result will prompt a flurry of It is clear that the referendum result could create a new political reality on parliamentary activity, renewing the Prime Minister’s mandate until he 24 June. Businesses must be prepared to engage if they are to mitigate the stands down closer to 2020 and enable a continuation of the impacts and take advantage of the opportunities presented. -

Ministers' Gifts

Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return MINISTERS’ GIFTS (GIVEN AND RECEIVED) GIFTS GIVEN OVER £140 Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Baroness Randerson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return GIFTS RECEIVED OVER £140 Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return Baroness Randerson, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil return Retained by the Department/ Purchased by the Minister/ Used for official entertainment Wales Office – Quarterly Ministerial Transparency Return MINISTERS’ HOSPITALITY HOSPITALITY RECEIVED Rt. Hon David Jones MP, Secretary of State for Wales Date of Name of organisation - Type of hospitality received hospitality 4 October Fast Growth 50 Dinner 10 October EADS Lunch & Canapes 11 October European Space Agency Lunch Stephen Crabb MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales Date of Name of organisation - Type of hospitality -

Read the Report

Will HUTTON Sir Malcolm RIFKIND Con COUGHLIN Peter TATCHELL Does West know best? bright blue AUTUMN 2011 flickr.com/familymwr Contributors Matt Cavanagh is the Associate Director for UK Migration Policy at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) Con Coughlin is the Executive Foreign Editor of The Daily Telegraph Sir Malcolm Rifkind MP Brendan Cox is the Director of Policy and Advocacy at Save the Children Stephen Crabb MP is MP for Preseli Pembrokeshire and Leader of Project Umubano, the Conservatives’ social action project in Rwanda and Sierra Leone Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles Maurice Fraser is a Senior Fellow in European Politics at the London School of Economics (LSE) and an Associate Fellow at Chatham House Peter Tatchell Will Hutton is a columnist for The Observer , executive vice-chair of The Work Foundation and Principal of Hertford College, Oxford University Professor Eric Kaufmann is Professor of Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London, the author of Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth and was a Visiting Fellow at the Kennedy School, Harvard in 2008-9. Sir Malcolm Rifkind MP is MP for Kensington and was Foreign Secretary, 1995-7 Victoria Roberts is Deputy Chairman of the Tory Reform Group Will Hutton Henneke Sharif is an Associate at Counterpoint and a Board Member of Bright Blue Guy Stagg is the Online Lifestyle Editor for The Daily Telegraph Peter Tatchell is a human rights campaigner Garvan Walshe is the Publications Director -

Web of Power the UK Government and the Energy- Finance Complex Fuelling Climate Change March 2013

Media briefing Web of power The UK government and the energy- finance complex fuelling climate change March 2013 Research by the World Development Movement has Government figures embroiled in the nexus of money and revealed that one third of ministers in the UK government power fuelling climate change include William Hague, are linked to the finance and energy companies driving George Osborne, Michael Gove, Oliver Letwin, Vince Cable climate change. and even David Cameron himself. This energy-finance complex at the heart of government If we are to move away from a high carbon economy, is allowing fossil fuel companies to push the planet to the government must break this nexus and regulate the the brink of climate catastrophe, risking millions of lives, finance sector’s investment in fossil fuel energy. especially in the world’s poorest countries. Introduction The world is approaching the point of no return in the Energy-finance complex in figures climate crisis. Unless emissions are massively reduced now, Value of fossil fuel shares on the London Stock vast areas of the world will see increased drought, whole Exchange: £900 billion1 – higher than the GDP of the countries will be submerged and falling crop yields could whole of sub-Saharan Africa.2 mean millions dying of hunger. But finance is continuing to flow to multinational fossil fuel companies that are Top five UK banks’ underwrote £170 billion in bonds ploughing billions into new oil, gas and coal energy. and share issues for fossil fuel companies 2010-12 – more than 11 times the amount the UK contributed in The vested interests of big oil, gas and coal mining climate finance for developing countries.3 companies are in favour of the status quo.