Research Article Documentation of Significant Losses in Cornus Florida L. Populations Throughout the Appalachian Ecoregion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborwoods Right Plant, Right Place Plant Selection Guide

“Right Plant, Right Place” Plant Selection Guide Compiled by Samuel Kelleher, ASLA April 2014 - Shrubs - Sweet Shrub - Calycanthus floridus Description: Deciduous shrub; Native; leaves opposite, simple, smooth margined, oblong; flowers axillary, with many brown-maroon, strap-like petals, aromatic; brown seeds enclosed in an elongated, fibrous sac. Sometimes called “Sweet Bubba” or “Sweet Bubby”. Height: 6-9 ft. Width: 6-12 ft. Exposure: Sun to partial shade; range of soil types Sasanqua Camellia - Camellia sasanqua Comment: Evergreen. Drought tolerant Height: 6-10 ft. Width: 5-7 ft. Flower: 2-3 in. single or double white, pink or red flowers in fall Site: Sun to partial shade; prefers acidic, moist, well-drained soil high in organic matter Yaupon Holly - Ilex vomitoria Description: Evergreen shrub or small tree; Native; leaves alternate, simple, elliptical, shallowly toothed; flowers axillary, small, white; fruit a red or rarely yellow berry Height: 15-20 ft. (if allowed to grow without heavy pruning) Width: 10-20 ft. Site: Sun to partial shade; tolerates a range of soil types (dry, moist) Loropetalum ‘ZhuZhou’-Loropetalum chinense ‘ZhuZhou’ Description: Evergreen; It has a loose, slightly open habit and a roughly rounded to vase- shaped form with a medium-fine texture. Height: 10-15 ft. Width: 10-15ft. Site: Preferred growing conditions include sun to partial shade (especially afternoon shade) and moist, well-drained, acidic soil with plenty of organic matter Japanese Ternstroemia - Ternstroemia gymnanthera Comment: Evergreen; Salt spray tolerant; often sold as Cleyera japonica; can be severely pruned. Form is upright oval to rounded; densely branched. Height: 8-10 ft. Width: 5-6 ft. -

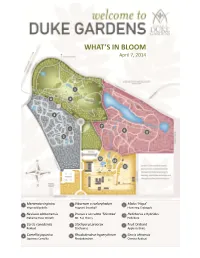

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

Dogwood Anthracnose by the Bartlett Lab Staff

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Dogwood Anthracnose By The Bartlett Lab Staff Anthracnose caused by the fungus Discula destructiva is a potentially fatal disease of dogwood. All varieties of the native flowering dogwood (Cornus florida and C. nuttallii) are susceptible. The disease usually starts on lower leaves and progresses into twigs and branches. Infected trees are severely weakened so that secondary canker and root rot diseases can infect and kill the tree. Discula infection usually occurs during cool, rainy periods in the spring. The fungal spores are spread by rain and wind. Symptoms branches (water sprouts) are more susceptible to the fungus. Often, the first symptoms of Discula destructiva anthracnose are spots on the lower leaves and flower The speed at which the disease progresses in the tree bracts. Spots are tan to brown and may have purple depends on weather, tree health, and treatment. With rings around them (Figure 1). This symptom is similar weather favorable to the disease and no treatments, to small spots caused by the fungus Elsinoe corni. If the most infected trees are killed within 3 to 6 years. infection is caused by Discula, leaf tissue will also be killed along the veins or the entire leaf will be killed. Management Those leaves which succumb to infection during the Healthy dogwoods are able to withstand disease summer will stay on the plant after normal leaf. The infection much better than stressed trees. To keep trees infection will also spread from the leaves to the twigs vigorous they should be mulched, watered, fertilized, resulting in cankers and twig dieback. -

Fungi and Their Potential As Biological Control Agents of Beech Bark Disease

Fungi and their potential as biological control agents of Beech Bark Disease By Sarah Elizabeth Thomas A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences Royal Holloway, University of London 2014 1 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Sarah Elizabeth Thomas, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: _____________ Date: 4th May 2014 2 ABSTRACT Beech bark disease (BBD) is an invasive insect and pathogen disease complex that is currently devastating American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in North America. The disease complex consists of the sap-sucking scale insect, Cryptococcus fagisuga and sequential attack by Neonectria fungi (principally Neonectria faginata). The scale insect is not native to North America and is thought to have been introduced there on seedlings of F. sylvatica from Europe. Conventional control strategies are of limited efficacy in forestry systems and removal of heavily infested trees is the only successful method to reduce the spread of the disease. However, an alternative strategy could be the use of biological control, using fungi. Fungal endophytes and/or entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) could have potential for both the insect and fungal components of this highly invasive disease. Over 600 endophytes were isolated from healthy stems of F. sylvatica and 13 EPF were isolated from C. fagisuga cadavers in its centre of origin. A selection of these isolates was screened in vitro for their suitability as biological control agents. Two Beauveria and two Lecanicillium isolates were assessed for their suitability as biological control agents for C. -

0118 Virginia State Flower, Tree, & Bird

VA STATE FLOWER, TREE AND BIRD The Cardinal and Dogwood Virginia's flowering dogwood has been the Crested, short-winged, long-tailed birds, official floral emblem of the state since March 1918 cardinals, are from seven and a half to nine and a when it edged out Virginia creeper by one vote. Then quarter inches long, with a wingspread of from 10 on January 25, 1950, the cardinal became the official 1/4 to 12 inches. The male is red except for a grayish state bird of Virginia. tone on the back, wings and tall and a black patch The flowering dogwood, Cornus florida, is a from the upper throat surrounding the red beak. The large shrub or small tree that usually grows from four female is olive grayish on the head and body, with a to 12 feet tall, though individual trees often attain dull red on the bill, crest, wings and tall. The bill patch much greater heights. It has very rough bark and is state colored, and the underparts are yellowish spreading branches. The wood, close grained and brown. Young cardinals resemble the female except hard, is used especially for shuttles and cogs in textile for their dark beaks. machinery and for inlaying in fine cabinet work. In March the flocks break up into mated pairs and What we speak of as the “flower” is a small nesting gets under way. The bulk), nests are loosely compact cluster of inconspicuous greenish-white true built of twigs, leaves, bark strips, rootlets, weed flowers surrounded by large showy petal-like bracts stems and grasses. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

Landscape Plants Rated by Deer Resistance

E271 Bulletin For a comprehensive list of our publications visit www.rce.rutgers.edu Landscape Plants Rated by Deer Resistance Pedro Perdomo, Morris County Agricultural Agent Peter Nitzsche, Morris County Agricultural Agent David Drake, Ph.D., Extension Specialist in Wildlife Management The following is a list of landscape plants rated according to their resistance to deer damage. The list was compiled with input from nursery and landscape professionals, Cooperative Extension personnel, and Master Gardeners in Northern N.J. Realizing that no plant is deer proof, plants in the Rarely Damaged, and Seldom Rarely Damaged categories would be best for landscapes prone to deer damage. Plants Occasionally Severely Damaged and Frequently Severely Damaged are often preferred by deer and should only be planted with additional protection such as the use of fencing, repellents, etc. Success of any of these plants in the landscape will depend on local deer populations and weather conditions. Latin Name Common Name Latin Name Common Name ANNUALS Petroselinum crispum Parsley Salvia Salvia Rarely Damaged Tagetes patula French Marigold Ageratum houstonianum Ageratum Tropaeolum majus Nasturtium Antirrhinum majus Snapdragon Verbena x hybrida Verbena Brugmansia sp. (Datura) Angel’s Trumpet Zinnia sp. Zinnia Calendula sp. Pot Marigold Catharanthus rosea Annual Vinca Occasionally Severely Damaged Centaurea cineraria Dusty Miller Begonia semperflorens Wax Begonia Cleome sp. Spider Flower Coleus sp. Coleus Consolida ambigua Larkspur Cosmos sp. Cosmos Euphorbia marginata Snow-on-the-Mountain Dahlia sp. Dahlia Helichrysum Strawflower Gerbera jamesonii Gerbera Daisy Heliotropium arborescens Heliotrope Helianthus sp. Sunflower Lobularia maritima Sweet Alyssum Impatiens balsamina Balsam, Touch-Me-Not Matricaria sp. False Camomile Impatiens walleriana Impatiens Myosotis sylvatica Forget-Me-Not Ipomea sp. -

Spring Ephemerals)

1 Sex Lives of Woodland Herbs Spring in the forest begins with a smorgasbord of flowering herbs. Hillsides become carpeted in white, pink, and maroon as trillium flowers open. The yellow bell-shaped flowers and mottled leaves of trout lily blaze in the April sunlight. Yellow, white, and blue violets flower in profusion along trails and creeks. Squirrel corn (Dicentra canadensis) flowers flavor the air with a sweet aroma (Figure Spring Ephemerals). The early woodland herbs, or spring ephemerals, spring forth quickly with leaves, flowers, and fruits and then wither just as summer heats up. Their strategy is to perform energy demanding activities quickly while sunlight abounds under the bare forest trees. In a few short weeks, many of these perennials will shift from a cryptic underground phase to a robust plant with conspicuous flowers only to return to hiding by July. The above ground growth phase is never prolonged. April trillium flowers progress to fruits and seeds in late July. Trout lily (Erythronium americanum), on the other hand, has one of the shortest above ground periods. They send both leaves and flowers to the surface in early April, then six weeks later the plant senesces as the fruit capsule lies quietly on forest soil. Special contractile roots, common among lily members, pull the expanding trout lily corm further beneath the soil. The large, colorful spring ephemeral flowers advertise their pollen and nectar rewards to early flies and bees in the forest. Insects are efficient and abundant pollinators on warm sunny days in the spring forest. Insect pollinators feed intensively with deliberate flights between flowers. -

Planting on Slopes (Plants All Native to Connecticut)

Planting on Slopes (plants all native to Connecticut) Compiled by North Central Conservation District, Ruth Klue General Considerations 1. Tops of slopes are generally drier than you might think, since water tends to drain downhill instead of soaking into the soil. Use plants that should be able to survive without irrigation, since soil erodes from slopes saturated with irrigation water. Study different areas of your slope to determine naturally-occuring variance of moisture and light levels. 2. Use a variety of mostly native shrubs, perennials, and grasses for the best slope protection. The varying plants will have root systems of varying depths, stabilizing more area of slope soil. Planting younger vegetation tends to result, in the long run, in more successful root systems. 3. Don’t plant big trees with heavy canopies or shallow roots. There is a risk that the trees could topple, or that heavy shade from the trees could kill undergrowth, leaving bare soil susceptible to erosion. If you wish to plant trees on the slope, use smaller trees, sparingly, and keep lower vegetation growing underneath them. 4. While turf grass on slopes helps reduce raindrop-type erosion, its roots are shallow, which can lead to clumps of grass sliding downhill in wet conditions. 5. Mulch in between plants until they grow to fill in the area. Mulch helps hold the soil, and prevents growth of invasive plants. 6. Many of the recommended plants spread by rhizomes and runners, and can often colonize and stabilize a slope quite successfully. If you wish to prevent colonizing beyond the slope, contain with an edging. -

Beyond Phenological Onset Dates: Using Observational Data to Detect the Effects of Climate on Collective Properties of Communit

Beyond phenophase onset dates: using observational data to link climate to the collective properties of communities and floras Susan J. Mazer University of California, Santa Barbara Director, California Phenology Project California poppy (Eschscholzia californica) NPN data can now be used to: (1) Compare closely related taxa occupying contrasting climates to examine how phenological sensitivity has diverged. (2) Detect the effects of climatic conditions on community-level phenological metrics (e.g., interspecific variance or synchrony in flowering onset). (3) Identify the climatic parameters that best explain variation in flowering metrics (e.g., flowering onset, duration, termination date, and multiple cycles of flowering) (4) Validate (or question) models constructed using herbarium data. NPN data can be used to: (1) Compare closely related taxa occupying contrasting climates to examine how phenological sensitivity has diverged. 2017. 105: 1610-1622 Western vs. Eastern Oaks • Both groups of oaks respond to warmer/drier conditions by advancing vegetative bud break and/or the onset of flowering • The California oaks are less sensitive to variation in temperature and rainfall across their range • Individual California oak trees have multiple episodes of bud break and flowering each year, while trees of the Eastern oaks exhibit a single event. • Whether these patterns apply to other genera is unknown. NPN data can be used to: (1) Compare closely related taxa occupying contrasting climates to examine how phenological sensitivity has diverged. (2) Detect the effects of climatic conditions on community-level phenological metrics (e.g., interspecific synchrony in flowering onset). (3) Identify the climatic parameters that best explain variation in flowering metrics (4) Validate or question models constructed using herbarium data. -

Forcing Branches for Winter Color B

Indoor Horticulture • HO-23-W Department of Horticulture Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service • West Lafayette, IN Forcing Branches for Winter Color B. Rosie Lerner and Michael N. Dana Does the bleak, cold dullness of winter sometimes get Next, put the branches in a container which will hold you down? Then why not bring springtime into your home them upright. Add warm water (110°F) no higher than 3 by forcing tree and shrub branches into bloom? Branches inches on the stems. A flower preservative will help can be used as background for an arrangement or for an prolong the vase life of the branches (see Figure 1 for entire floral display, and you can prune your shrubs and preservative recipes). Allow to stand for 20-30 minutes, trees as you selectively remove branches for forcing. and then fill the container with additional preservative solution. Place the container in a cool (60-65°F), partially Early spring flowering trees and shrubs form their flower shaded location. Keep the water level at its original buds in the fall before the plants go dormant. After a height. period of at least 8 weeks of temperatures below 40°F (usually after January 1), branches can be cut and forced Finally, when the buds show color, move the branches to into bloom. a lighted room. But don’t put them in direct sunlight. At this time they can be removed from the storage container Most flowering shrubs are fairly easy to force, while trees and arranged in the desired manner. Be sure the ar are more difficult. -

Ecological Zones in the Southern Appalachians: First Approximation

United States Department of Ecological Zones in the Southern Agriculture Forest Service Appalachians: First Approximation Steve A. Simon, Thomas K. Collins, Southern Gary L. Kauffman, W. Henry McNab, and Research Station Christopher J. Ulrey Research Paper SRS–41 The Authors Steven A. Simon, Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; Thomas K. Collins, Geologist, USDA Forest Service, George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Roanoke, VA 24019; Gary L. Kauffman, Botanist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; W. Henry McNab, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC 28806; and Christopher J. Ulrey, Vegetation Specialist, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway, Asheville, NC 28805. Cover Photos Ecological zones, regions of similar physical conditions and biological potential, are numerous and varied in the Southern Appalachian Mountains and are often typified by plant associations like the red spruce, Fraser fir, and northern hardwoods association found on the slopes of Mt. Mitchell (upper photo) and characteristic of high-elevation ecosystems in the region. Sites within ecological zones may be characterized by geologic formation, landform, aspect, and other physical variables that combine to form environments of varying temperature, moisture, and fertility, which are suitable to support characteristic species and forests, such as this Blue Ridge Parkway forest dominated by chestnut oak and pitch pine with an evergreen understory of mountain laurel (lower photo). DISCLAIMER The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement of any product or service by the U.S.