Methods and Quality Assurance for Chesapeake Bay Water Quality Monitoring Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

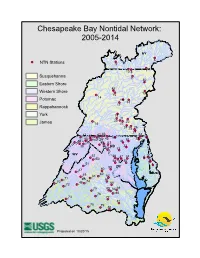

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and Issues for Congress

Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and Issues for Congress Updated August 3, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45278 SUMMARY R45278 Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and August 3, 2018 Issues for Congress Eva Lipiec The Chesapeake Bay (the Bay) is the largest estuary in the United States. It is Analyst in Natural recognized as a “Wetlands of International Importance” by the Ramsar Convention, a Resources Policy 1971 treaty about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for migratory waterbirds. The Chesapeake Bay estuary resides in a more than 64,000-square-mile watershed that extends across parts of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The Bay’s watershed is home to more than 18 million people and thousands of species of plants and animals. A combination of factors has caused the ecosystem functions and natural habitat of the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed to deteriorate over time. These factors include centuries of land-use changes, increased sediment loads and nutrient pollution, overfishing and overharvesting, the introduction of invasive species, and the spread of toxic contaminants. In response, the Bay has experienced reductions in economically important fisheries, such as oysters and crabs; the loss of habitat, such as underwater vegetation and sea grass; annual dead zones, as nutrient- driven algal blooms die and decompose; and potential impacts to tourism, recreation, and real estate values. Congress began to address ecosystem degradation in the Chesapeake Bay in 1965, when it authorized the first wide-scale study of water resources of the Bay. Since then, federal restoration activities, conducted by multiple agencies, have focused on reducing pollution entering the Chesapeake Bay, restoring habitat, managing fisheries, protecting sub-watersheds within the larger Bay watershed, and fostering public access and stewardship of the Bay. -

Summary of Public Comments to State Water Control Board Adequacy of NWP 12 to Ensure Compliance with State Standards

Summary of Public Comments to State Water Control Board Adequacy of NWP 12 to Ensure Compliance with State Standards Prepared by Wild Virginia Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition (DPMC) August 15, 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary . 7 I. Overall Body of Comments and Organization of the Online Records . 10 II. Waterbodies Discussed . 12 Mountain Valley Pipeline New River Basin Kimballton Branch . 14 (tributary to Stony Creek) Stony Creek . 15 (aka Big Stony Creek - tributary to New River) Little Stony Creek . 15 (tributary to New River) Doe Creek . 16 (tributary to New River) Greenbriar Branch . 17 (tributary to Sinking Creek) Unnamed Tributary to Grass Run . 17 (tributary to Grass Run) Sinking Creek . 18 (tributary to New River) James River Basin Craig Creek . 19 (tributary to James River) Roanoke River Basin Bottom Creek, Mill Creek, and Tributaries . 20 (tributary to South Fork Roanoke River) South Fork Roanoke River . 22 (tributary to Roanoke River) Mill Creek (Montogomery Co.) . 23 (tributary to North Fork Roanoke River) Bottom Spring . 24 (tributary to North Fork Roanoke River) Salmon Spring . 24 (tributary to North Fork Roanoke River) 2 Bradshaw Creek . 25 (tributary to North Fork Roanoke River) Flatwoods Branch . 25 (tributary to North Fork Roanoke River) North Fork Roanoke River . 25 (tributary to Roanoke River) North Fork Blackwater River . 26 (tributary to Blackwater River) Green Creek . 27 (tributary to South Fork Blackwater River) Teels Creek . 27 (tributary to Little Creek) Little Creek . 28 (tributary to Blackwater River) Blackwater River . 28 (tributary to Roanoke River - Smith Mtn. Lake) Pigg River . 29 (tributary to Roanoke River - Leesville Lake) Roanoke River . -

New York Buffer Action Plan

Chesapeake Bay Buffer Action Strategy for New York Current Effort Based on the targets set in New York’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan, New York plans to implement 2,606 acres of forest buffer and 1,020 acres of grass buffers in the agriculture sector by 2025. In the urban sector, New York plans to implement 3,095 acres of forest buffer and 1,853 acres of tree planting by 2025. Table 1 shows the current progress in 2020 towards achieving riparian forest buffer targets, the percent achieved, and acres remaining. Table 1 Amount of riparian forest buffer and tree plantings to achieve NY’s WIP III. Best Management Practice 2020 WIP III Percent Acres Acres Progress (acres) Achieved Remaining Needed (acres) per Year Pasture Forest Buffers 2,058 3,543 58% 1,485 297 Pasture Grass Buffers 1,166 1,815 64% 649 130 Cropland Forest Buffers 1,003 2,124 47% 1,121 224 Cropland Grass Buffers 405 776 52% 371 74 Urban Forest Buffers 37 3,132 1% 3,095 619 Opportunities for Implementation Participating Partners New York’s key partners in buffer implementation are the Department of Environmental Conservation, Department of Agriculture and Markets, Upper Susquehanna Coalition, and Soil and Water Conservation Districts. Partners to be further engaged include Farm Service Agency, National Resources Conservation Service, local communities, nongovernment organizations, land trusts and members of the Climate Action Council. Strategy for Implementation As outlined in the Phase III WIP, New York proposes the following strategies to improve its riparian buffer delivery including increase voluntary implementation, explore new funding strategies, sustaining motivation and continuing to support technical capacity. -

Signal Knob Northern Massanutten Mountain Catback Mountain Browns Run Southern Massanutten Mountain Five Areas of Around 45,000 Acres on the Lee the West

Sherman Bamford To: [email protected] <[email protected] cc: Sherman Bamford <[email protected]> > Subject: NiSource Gas Transmission and Storage draft multi-species habitat conservation plan comments - attachments 2 12/13/2011 03:32 PM Sherman Bamford Forests Committee Chair Virginia Chapter – Sierra Club P.O. Box 3102 Roanoke, Va. 24015 [email protected] (540) 343-6359 December 13, 2011 Regional Director, Midwest Region Attn: Lisa Mandell U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ecological Services 5600 American Blvd. West, Suite 990 Bloomington, MN 55437-1458 Email: [email protected] Dear Ms. Mandell: On behalf of the Virginia Chapter of Sierra Club, the following are attachments to our previously submitted comments on the the NiSource Gas Transmission and Storage (“NiSource”) draft multi-species habitat conservation plan (“HCP”) and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (“Service”) draft environmental impact statement (“EIS”). Draft of Virginia Mountain Treasures For descriptions and maps only. The final version was published in 2008. Some content may have changed between 2007 and 2008. Sherman Bamford Sherman Bamford PO Box 3102 Roanoke, Va. 24015-1102 (540) 343-6359 [email protected] Virginia’s Mountain Treasures ART WORK DRAWING The Unprotected Wildlands of the George Washington National Forest A report by the Wilderness Society Cover Art: First Printing: Copyright by The Wilderness Society 1615 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 (202)-843-9453 Wilderness Support Center 835 East Second Avenue Durango, CO 81302 (970) 247-8788 Founded in 1935, The Wilderness Society works to protect America’s wilderness and to develop a nation- wide network of wild lands through public education, scientific analysis, and advocacy. -

SR V18 Index.Pdf (969.3Kb)

Index to Volume 18 Rachael Garrity A Biedma, 115 A Girls Life Before the War, 81 Bimini, 119 Adams, President John, I 0, 13-14 Blacksburg, Va., 25, 30, 57, 80, 82-85, 91 Alabama, IOI Blue Ridge Mountains, 82 Alien and Sedition Acts, I 0 Boston, Barbara, 112 Alonso de Chavez, 115 Botetourt County, Va., 25, 27, 29, 54, 63, Alonso de Santa Cruz, 111-113 65, 79 Allegheny Mountains, 82 Bouleware, Jane Grace Preston, 78 American Declaration of Independence, 9 Boulware, Aubin Lee, 78 American Indians, 4, 52-54, 58, 66, 82, Bradenton, Fla., I 06 100, 105, 107-108 Brady, Mathew, 84 American Revolution, 58, 72, 73 Braham, John, 34 Apafalaya, I 0 I Brain, Jeffrey, I 05 Appalachia, I 0 I, I 04 Breckenridge, Robert, 40 Appalachian Mountains, 3, 20, 55 Brissot, Jacques Pierre, 16 Appalachian Trail, 110 Bristol, Tenn.Na., 99, I 09, 124 Arkansas, I 05 Bristol News, 126-127 Augusta County, Va., 25-27, 30, 33, 35, British North America, 55 37-38,40,43-44,52,54, 71 Brown, John, 91, 135 Avenel House Plantation, 81 Brown, John Mason, 135 Brown, John Meredith, 135 B Brunswick County, Va., 40 Bahaman Channel, 118-119 Buchanan, Colonel John, 27, 30, 35, 41, Baird (Beard), John, 40-41 52-53 Baldwin, Caroline (Cary) Marx, 78 Buchanan, Va., 27, 38, 52-53 Bank of the United States, 6 Bullett, Captain, 62-65 Bardstown, Ky., 3, 17 Bullpasture River, 54 Barreis, David, I 05 Bureau ofAmerican Ethnology, 110 Barrens, The, Ky., 13, 17 Burke County, N.C., I 03 Bassett, Colonel, 65 Burwell, Letitia M., 81-83, 86, 90 Batson, Mordecai, 60 Bussell Island, Tenn., 123 Battle -

A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 "Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800 Wendy Sacket College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sacket, Wendy, ""Peopling the Western Country": A Study of Migration from Augusta County, Virginia, to Kentucky, 1777-1800" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625418. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ypv2-mw79 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "PEOPLING THE WESTERN COUNTRY": A STUDY OF MIGRATION FROM AUGUSTA COUNTY, VIRGINIA, TO KENTUCKY, 1777-1800 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Wendy Ellen Sacket 1987 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December, 1987 John/Se1by *JU Thad Tate ies Whittenburg i i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................. iv LIST OF T A B L E S ...............................................v LIST OF MAPS . ............................................. vi ABSTRACT................................................... v i i CHAPTER I. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERATURE, PURPOSE, AND ORGANIZATION OF THE PRESENT STUDY . -

Module 1 Overview

Module 1 Educator’s Guide Overview What’s up with Geography Standards World in Spatial Terms Earth’s water • Standard 1: How to use maps and other geographic representations, tools, and technologies to acquire, resources? process, and report information from a spatial perspective Places and Regions Module Overview • Standard 4: The physical and This module addresses issues that are of human characteristics of places fundamental importance to life. Four case Physical Systems studies of a coastal bay, an inland sea, a river, and mountain snow pack • Standard 7: The physical pro- investigate water resources important to millions of people in North cesses that shape the patterns of America, Asia, and Africa. Each investigation focuses on the physical Earth’s surface nature of the resource, how humans depend upon the resource, and how • Standard 8: Characteristics and human use affects the resource creating both problems and opportunities. distribution of ecosystems Environment and Society Investigation 1: Chesapeake Bay: Resource use or abuse? • Standard 14: How humans modify Students play roles of concerned citizens, public officials, and scientists the physical environment • while learning about the Chesapeake Bay and its environs. They use data Standard 15: How physical and satellite images to examine how human actions can degrade, im- systems affect human systems prove, or maintain the quality of the bay in order to make policy recom- The Uses of Geography • Standard 18: How to apply mendations for improving this resource for future use. geography to interpret the present and plan for the future Investigation 2: What is happening to the Aral Sea? Students work as teams of NASA geographers using satellite images to measure the diminishing size of the Aral Sea. -

Environmental Literacy in Delaware

DELAWARE CHESAPEAKE BAY WATERSHED PORTION Environmental Literacy in Delaware Why environmental literacy? How does Delaware compare to the The well-being of the Chesapeake Bay watershed Chesapeake Bay watershed? will soon rest in the hands of its youngest citizens: 2.7 Environmental Literacy Planning: School districts’ self-identified preparedness million students in kindergarten through twelfth grade. to put environmental literacy programs in place Establishing strong environmental education programs Delaware now provides a vital foundation for these future stew- 63% 25% 13% ards. Chesapeake Bay watershed Along with Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and 9% 24% 8% 59% Washington, D.C., Delaware has committed to helping Well-prepared Somewhat prepared its students graduate with the knowledge and skills Not prepared Non-reporting needed to act responsibly to protect and restore their local watersheds. They will do this through: Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences (MWEEs): School districts that reported providing MWEEs to their students • Environmental Literacy Planning: Developing a MWEE Availability in Elementary Schools comprehensive and systemic approach to environ- Delaware mental literacy for students that includes policies, 13% 25% 50% 13% practices and voluntary metrics. Chesapeake Bay watershed • Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences 16% 13% 11% 59% (MWEEs): Continually increasing students’ under- MWEE Availability in Middle Schools standing of the watershed through participation in Delaware teacher-supported Meaningful Watershed Edu- 50% 13% 25% 13% cational Experiences and rigorous, inquiry-based Chesapeake Bay watershed instruction. 18% 14% 9% 59% MWEE Availability in High Schools • Sustainable Schools: Continually increasing the number of schools that reduce the impact of their Delaware buildings and grounds on the environment and 25% 25% 38% 13% human health. -

Strategies for Financing Chesapeake Bay Restoration in New York State

StrategiesPrepared by the for University Financing of Maryland Chesapeake Environmental Bay Finance Center and the Syracuse University Environmental Finance RestorationCenter for the Chesapeake in New YorkBay Program State Office and the State of New York February 2019 efc.umd.edu efc.syr.edu Prepared by the University of Maryland Environmental Finance Center and the Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center for the Chesapeake Bay Program Office and the State of New York March 2019 efc.umd.edu efc.syr.edu - 1 - This report was prepared by the Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland (UMD-EFC) and the Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center (SU-EFC), with funding from the US EPA Chesapeake Bay Program Office. The EFC project team included Kristel Sheesley, Jen Cotting, Khris Dodson, and Bill Whipps. EFC would like to thank the following individuals for their input and feedback: Greg Albrecht, New York Department of Agriculture and Markets; Ruth Izraeli, Chesapeake Bay Program Office; Ben Sears, New York Department of Environmental Conservation; Lauren Townley, New York Department of Environmental Conservation, and Wendy Walsh, Upper Susquehanna Coalition. Cover photos courtesy of Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center. About the Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland The Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland is part of a network of university-based centers across the country that works to advance finance solutions to environmental challenges. Our focus is protecting natural resources by strengthening the capacity of decision-makers to analyze challenges, develop effective financing methods, and build consensus to catalyze action. Through research, policy analysis, and direct technical assistance, we work to equip communities with the knowledge and tools they need to create more sustainable environments, more resilient societies, and more robust economies. -

Table of Contents

William2 Gay of the Little Calfpasture 1 PREFACE This is an excerpt from a much longer report which represents my current thinking on the many Scotch- Irish families surnamed Gay who pioneered in the Valley of Virginia (the Shenandoah) in the 1740s. This excerpt is focused on William2 Gay (a.k.a. William-A Gay), one of the two such Williams (the other I call William-B) who settled on the Little Calfpasture River in the present county of Rockbridge. In order to call my subject William2 Gay (implying that his parents were the first immigrants to America of his line), I must logically provide some account of those parents, and this I have done below, although it must be noted that they remain rather shadowy figures—theoretical constructs based largely on onomastic analysis of the child-naming patterns in the families of their putative descendants. The children of this first couple, whom I hypothesize were named John1 and Agnes, were, in probable order of birth: William, James, John, Robert, Samuel, and Eleanor. Of these, besides William, the only one for whom I have included material here from my plenary report is Eleanor, and that only because her inclusion crucially impacts the structure of this family, and also uniquely brings into play evidence of its origins in Ulster—northern Ireland—probably either in the counties of Donegal or Londonderry. The main line of this report, as well as the plenary report from which it is excerpted, consists of a series of linked family sketches, in descendancy order. Each sketch covers one man, or one woman, their spouse or spouses, and their set or sets of children.